Iridomyrmex Purpureus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking with Ants Report by Arminel Ryan

Walking with Ants Report by Arminel Ryan With a mere 45 other participants, I joined lively young ANU myrmecologist, Dr. Ajay Narendra, for a glimpse into the fascinating world of ants - one of the most dominant animals on the planet. Waltraud Pix had organised the adventure, and had had an overwhelming response – more than 200 enquiries! So, at Mt Majura on Sunday 28 February, we fortunate few assembled at 4.30 p.m. for our educational ramble. Our troupe travelled only a short distance in the 2 hours, but the range of fascinating facts that had emerged by 6.30 p.m. was truly phenomenal. I expect you know that ants play a leading role in the environment as predators and scavengers. You may be aware that their social organisation, communication systems and amazing navigation skills have been the object of research for generations. Ajay led us deeper into this world, using a few of the 45 species found on Mount Majura to illustrate his subject. The following is a brief summary of what I gleaned. Australia has around 1,200 species of ant. Ants have evolved from a wasp-like ancestor. Ants differ from wasps (and bees) in three visible anatomical features – . their flexible, conical “waist”, which allows their rear section (called a “gaster”) to flex, . “elbows” in their feelers, and . a metapleural gland that produces antbiotics that helps to prevent the growth of bacteria, fungus, spores on the ant and in its nest. In common with some kinds of wasps and bees, certain ant stings can hurt animals much larger than themselves, but most are harmless to humans. -

Iridomyrmex Purpureus, and Its Taxonomic Significance

4 ¿l 'lcl GENETIC STUDIES OF MEAT A}ITS (tazaouvaunx PunPuaws) . by R, B. Hallida/, B.Sc.(Hons.) Department of Genetics University of Adelaide. A thesis subnitted to the University of Adelaide for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in May, 1978' TABLE QF 'CONTENTS Page SUMMARY i DECLARATION ].V ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION I CHAPTER 2 ECOLOGY AND SYSTET{ATICS OF MEAT A¡ITS 4 2,L Taxonomic background 4 2.2 Appearance of colour forms 7 2.3 Geographic distribution 10 2.4 Interactions between colour fonts T2 2.5 Mating and colony founding 15 2.6 Nest structure T7 2.7 Colony and popu3..ation structure 20 2.8 General biology and pest status 24 ?o 0verview 28 CHAPTER J MATERIALS AND METHODS 29 3 I Populations sanpled 29 3 2 Collection nethods 38 3.3 Sanple preparation 59 3.4 Electrophoresis nethods 40 3.5 Gel staining nethods 42 3.6 Chronosome nethods 47 CHAPTER 4 POLYMORPHISM AT TÍ{Ë AMYT,ASE LOCUS 48 4.L The phenotypes and their inheritance 48 4.2 Estination of gene frequencies 51 4.3 Geographic variation within forms 56 4.4 Differences anong forrns 58 POLYMORPHISM AT THE ESTERÄSE=] LOCUS 61 The phenotypes and their inheritance 6L Estination of gene frequencies 63 Within and between fo::rn variation 65 Discussion 67 CHAPTER 6 OTHER ISOZYME LQCI IN MEAT ANTS 69 6.1 Aldehgde. oxÍdase 69 6.2 Esüerase-2 70 6.3 Esterase:3 72 6.4 General protein 74 6.s G Tuco se*6 -.p/:o sphate dehgdrog enase 75 6.6 G Tutamate dehgclrogenase 76 6.7 Lactate dehgdrogenase 77 6.8 Leucíne amÍnopeptÌdase 78 6.9 I{alate dehgdrogenase 79 6. -

Meat Ants (Iridomyrmex Purpureus) Are Native to Australia and Are Most Common in Country Areas

July 2018 Factsheet Meat ants (Iridomyrmex purpureus) Ants to watch out for Red imported fire ants, yellow crazy ants, electric ants and carpenter ants, all pose a serious social, economic and environmental threat to Western Australia. If you suspect you have these ants or any ants you haven’t seen before, please contact us on freecall 1800 084 881. Summary Meat ants (Iridomyrmex purpureus) are native to Australia and are most common in country areas. These ants do not sting but are very territorial and will bite aggressively when disturbed. Where are they found? Meat ants build large nests which resemble roughly circular low lying mounds, often covered with small pebbles and Meat ant (Iridomyrmex purpureus) and free of any vegetation. The mounds are usually located in meat ant mound (bottom image) open, sunny areas. Damage These ants do not damage or nest in buildings. They can be a nuisance because of their aggressive territorial behaviour and can bite people, pets and livestock. They are also known to transport aphids and scale insects onto Contact trees in orchards which encourage outbreaks of these pests. Pest and Disease Information Service (PaDIS) Treatment Call: (08) 9368 3080 Any insecticide sprays registered for ant control can be used to treat meat ant mounds and greatly reduce or Email: [email protected] eliminate meat ant numbers; registered chemicals include bifenthrin, permethrin and chlorpyrifos. Follow the mixing instructions on the pack and spray the mounds, including approximately 100 mL down every hole. These spray products can be purchased from garden centres, hardware stores and agricultural chemical retailers. -

Hymenoptera, Formicidae) 1 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.700.11784 Research Article Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 700: 1–420 (2017)Revision of the ant genus Melophorus (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.700.11784 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Revision of the ant genus Melophorus (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) Brian E. Heterick1,2, Mark Castalanelli3, Steve O. Shattuck4 1 Curtin University of Technology, GPO Box U1987, Perth WA, Australia, 6845 2 Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC. WA, Australia, 6986 3 EcoDiagnostics Pty Ltd, 48 Banksia Rd, Welshpool WA 6106 4 C/o CSIRO Entomology, P. O. Box 1700, Canberra, Australia, ACT 2601 Corresponding author: Brian Heterick ([email protected]) Academic editor: B. Fisher | Received 17 January 2017 | Accepted 22 June 2017 | Published 20 September 2017 http://zoobank.org/EBA43227-20AD-4CFF-A04E-8D2542DDA3D6 Citation: Heterick BE, Castalanelli M, Shattuck SO (2017) Revision of the ant genus Melophorus (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). ZooKeys 700: 1–420. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.700.11784 Abstract The fauna of the purely Australian formicine ant genus Melophorus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) is revised. This project involved integrated morphological and molecular taxonomy using one mitochondrial gene (COI) and four nuclear genes (AA, H3, LR and Wg). Seven major clades were identified and are here designated as the M. aeneovirens, M. anderseni, M. biroi, M. fulvihirtus, M. ludius, M. majeri and M. potteri species-groups. Within these clades, smaller complexes of similar species were also identified and designated species-complexes. The M. ludius species-group was identified purely on molecular grounds, as the morphol- ogy of its members is indistinguishable from typical members of the M. -

Central Victoria & the Highlands

QUICK IDENTIFICATION OF COMMON LOCAL INSECTS CentralCentral VictoriaVictoria && thethe HighlandsHighlands QUICK IDENTIFICATION OF COMMON LOCAL INSECTS A simple educational guide A continuously growing database of some of the insects in the central Victorian bushland and Highland areas. The book is based almost entirely on images taken by people with local links or visitors to our district. In some instances we have used public domain images, though we aim to replace these with local images as contributions allow. By David & Debbie Hibbert Species count: 1 3 8 and growing Special thanks to Kathie Maynes, Kelly Petersen, Robert (Bob) Tate and Ron Turner. Contributing photographers: Bob Tate, Jamie Flynn, Kathie Maynes, John Norbury, Shez Tedford, Ron Turner, Joan Walsh, Joshua Hibbert, Steven Hibbert, Debbie Hibbert, David Hibbert. Project commenced January 2013 and was first published in May 2013 An Artworkz Publication ANTS & TERMITES CICADAS BUGS, BEETLES WEEVILS FLIES BEES & WASPS BUTTERFLIES MOTHS DRAGONFLIES GRASSHOPPERS & CRICKETS OTHER GLOSSARY ANTS & TERMITES BLACK ANT Also known as the Black House Ant, it is a worker ant found in all states of Australia. It grows to 3 mm and is an omnivorous ant that will often feed on sweet foods as well as worms, insects, spiders and vegetation. It will nest around homes, making it a common pest. The queen black ant lays oval eggs. Family: Formicidae Genus: Ochetellus Species: O. glaber VIC N.S.W QLD S.A. W.A. N.T. TAS NATIVE INTRODUCED ENDANGERED BULLDOG ANT Found in all states of Australia, it grows to 30 mm and is an aggressive hunter that feeds on other ants, spiders, bees and other insects. -

Wildlife Trade Operation Proposal - Queen Ant Harvesting

Wildlife Trade Operation Proposal - Queen Ant Harvesting 1. Title and Introduction 1.1/1.2 Scientific and Common Names Please refer to Attachment A, outlining the ant species subject to harvest, giving both scientific and common names where applicable (some species are only referred to by their scientific name) and the proposed annual harvest quota which will not be exceeded. 1.3 Location of harvest Harvest will be conducted on two privately owned properties in McCrae Victoria, and one privately owned property at Forrest Lake in Queensland. 1.4 Description of what is being harvested Please refer to Attachment A for an outline of the species to be harvested. The harvest is of live, newly mated, adult queen ants. 1.5 Is the species protected under State or Federal legislation Ants are non-listed invertebrates and are as such unprotected under Victorian or Queensland State Legislation. Under Federal legislation the only protection to these species relates to the export of native wildlife, which this application seeks to satisfy. No species listed under the EPBC Act as threatened (excluding the conservation dependent category) or listed as endangered, vulnerable or least concern under Victorian or Queensland legislation will be harvested. 2. Statement of general goal/aims The applicant began collecting queen ants and watching them build colonies as a personal hobby, during which time he has identified strong interest from international collectors in acquiring species of ants found in Australia. The goal of this application is to seek approval for a WTO to export queen ants. The ability to export queen ants will also increase the export sales of specialized ant keeping equipment, manufactured in Australia, to overseas ant keepers. -

Common Names for Australian Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

Australian Journal of Entomology (2002) 41, 285–293 Common names for Australian ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Alan N Andersen CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Tropical Ecosystems Research Centre, PMB 44, Winnellie, NT 0822, Australia. Abstract Most insects do not have common names, and this is a significant barrier to public interest in them, and to their study by non-specialists. This holds for even highly familiar insect groups such as ants. Here, I propose common names for all major native Australian ant genera and species-groups, as well as for many of the most abundant and distinctive species. Sixty-two genera, 142 species-groups and 50 species are given names. The naming system closely follows taxonomic structure; typically a genus is given a general common name, under which species-group and species names are nested. Key words ant species, communicating entomology, species-groups, taxonomic nomenclature. INTRODUCTION ‘little black ones’ (the remaining several thousand Australian species). Here, I attempt to redress this situation by propos- Common names are powerful aids for the popular communi- ing common names for all major native Australian ant genera cation of information about plant and animal species. Such and species-groups, as well as for many abundant and names use familiar and easily remembered words, in contrast distinctive species. to the taxonomic nomenclature that is so daunting for most people without formal scientific training. All higher-profile vertebrates and vascular plants have widely accepted common names. These increase the accessibility of these species to a PROPOSED ANT COMMON NAMES wide public audience, and promote interest in them. In Proposed common names, and explanations for them, for contrast, the vast majority of insects and other arthropods 62 genera, 142 species-groups and 50 species of Australian have no common name beyond the ordinal level, unless they ants are presented in Appendix I, Table A1. -

Barbed Wire Vine

Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Compiled by: Michael Fox www.megoutlook.org/flora-fauna/ © 2015-19 Creative Commons – free use with attribution to Mt Gravatt Environment Group Ants Dolichoderinae Iridomyrmex sp. Small Meat Ant Attendant “Kropotkin” ants with caterpillar of Imperial Hairstreak butterfly. Ants provide protection in return for sugary fluids secreted by the caterpillar. Note the strong jaws. These ants don’t sting but can give a powerful bite. Kropotkin is a reference to Russian biologist Peter Kropotkin who proposed a concept of evolution based on “mutual aid” helping species from ants to higher mammals survive. 30-May-20 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.8.docx Page 1 of 57 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Opisthopsis rufithorax Black-headed Strobe Ant Formicinae Camponotus consobrinus Banded Sugar Ant Size 10mm Eggs in rotting log 30-May-20 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.8.docx Page 2 of 57 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Camponotus nigriceps Black-headed Sugar Ant 30-May-20 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.8.docx Page 3 of 57 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Polyrhachis ammon Golden-tailed Spiny Ant Large spines at rear of thorax Nest 30-May-20 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.8.docx Page 4 of 57 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Polyrhachis australis Rattle Ant Black Weaver Ant or Dome-backed Spiny Ant Feeding on sugar secretions produced by Redgum Lerp Psyllid. -

The Victorian Naturalist

; msrnm The Victorian Naturalist Vol. XLV. MAY, 1928, TO APRIL, 1929 CONTENTS Field Naturalists* Club of Victoria :— pagk Annua! Report ...-..-•-..... 61 Exhibition of Wild Flowers- 182 Proceedings 1, 29, 57, »9, 121, 149, 173, 201, 225, 24R, 269, 283 Supplement to October Number, 52 pages. Western District Excursion (10 days), Reports* General, Pbysiographical, Geological, Botanreal and Entomological ~ and descriptions of four new species, after p. 172* LECTURETTES April 16th. 1928—On Scientific Sjudy -.. .. Dk T. 1), A.- Cockebrm., Univ., Colorado, U.S.A. May 14th— Western District Excursion, Ma. E. E. Fescott, V\L.S. Juno llth —Conversazione. July 9th—The Great Barrier Reef ...,.,,,, db. sidnky Psnw •• •• Tablton Raymiwt ,fc|iV Au8« 13th—Native Bees , - W<\ g™fe : '-; Sept. 10th—Aboriginal Stone Axes -.. Ma. C. Daiey, BA, F.L.S. Get. of River District, ,;;, »t'?- 8th—Animate and Plants the Daintree Q ? : W W&'- Mk - c - Barkett, C.M.Z.S. .j-^Vs,-^-; Nov. 12th—Natural History of "West Australia -;. Ma. J. CtAKK, F.L.S. Pulleixs ^fe^' Dec. 10th—Australian Trap-door Spiders . Dn. R, H. ^•s8-f-& Jan. 14th, 1929—Natural History of the Federal Capital Territory, DAtEY, SSi^V Mr - c - B,A„ FXJS- i'WSS^I'T^ llth— Beetle Pests of the Sugar Cane .. Ma. A. N, Bubns BBKm»&\- f^^gpMar. llth—Swans. Ducks and Geese , Da. J. A. Leach ' Ma:-. The Victorian Naturalist VOU XLV—JSJo, 1 MAY 9, 1928. No. 533. THE FIELD NATURALISTS' CLUB OF VICTORIA. The ordinary monthly meeting of the Club was held in the Royal Society's Hall. Victoria-street, Melbourne, on Monday, April 16th, 1928. -

Ant Control Made Simple Ant Control Made Simple

TM Ant control made simple Ant control made simple What is Synergy Pro ant bait and how does it work? Synergy Pro ant bait is the most advanced ant bait on the market, designed to make ant control simple. The unique, granular formulation contains • Two different food granules for broad spectrum control throughout the year • Two different actives to target worker and reproductive ants for complete colony control Why two different food granules? Why two different actives? Although some ant species tend to prefer a specific type To gain complete control, baits need to be spread of food, be it sugar, protein or oil, many ant species will throughout the colony and kill the queen. However, eat a wide range of foods. Furthermore, even ants with some baits work too fast and the colony detects the a particular preference often change their diet through- problem and stop feeding on the bait before it gets out the year to meet the requirements of the colony. to the queens. Other baits are not rejected by workers For example many ant species (even sugar feeders) will but are rejected by queens, as the queens appear to require food with a higher protein content when the be more sensitive to certain actives, making the bait colony is producing young. repellent. With most ant bait formulations containing only a single Either way it is not uncommon for baits to kill a large food group, pest professionals need to carry a range of number of workers, giving you the appearance of col- different baits. Knowing which bait to use for a particu- ony control. -

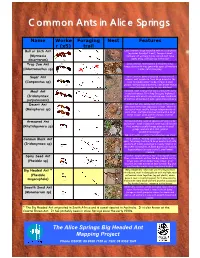

Common Ants in Alice Springs

CommonCommonCommon AntsAntsAnts ininin AliceAliceAlice SpringsSpringsSprings Name Worke Foraging Nest Features r (x5) trail Bull or Inch Ant Less common, large mounded nest in a cool place (eg under Eucalypt trees), forage in small (Myrmecia numbers, all workers 1 size, varied diet, have nasty sting, will look you in the eye! desertorum) 1mm Trap Jaw Ant 1mm Less common, nest may be difficult to find, forage alone with trap jaws wide open, all workers (Odontomachus sp) 1 size, catch live prey. Sugar Ant Very common, several species in a variety of colours, nest anywhere from large mound in the (Camponotus sp) open to hidden under rocks, forage in small 1mm groups, multiple sized workers, likes sweet things – may find paler species in your kitchen! Meat Ant Common, nest in large flat bare areas with many round entrances, form long foraging ‘highways’ with many ants which may extend over hundreds (Iridomyrmex 1mm purpurescens) of metres, all workers 1 size, general scavengers. Desert Ant Common but shy, sandy nest often in the open, ants move very fast especially in heat, ‘shoot’ in (Melophorus sp) and out of nest, mostly forage independently of each other, multiple sized workers with a large 1mm range in size, some with big heads, love hot weather! Armoured Ant Common but shy, several species varying in size and colour – some iridescent, nest may be hard to find, workers usually forage alone or in small (Rhytidoponera sp) 1mm groups, workers all 1 size, general predator/scavenger. NB: Ants with a constricted abdomen can sting! Common Black Ant Very common, inconspicuous nest often in the open, form busy trails with large numbers of ants, (Iridomyrmex sp) workers all 1 size, scavengers, closely related to 1mm Meat Ant but smaller, in some places can mass in huge numbers (on your patio?), smell when crushed. -

Wildlife Guide for Landholders in the Foothills and Upper Regions of the Goulburn Broken Catchment

11 Citation Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority, 2004. A Wildlife Guide for Landholders in the Upper Goulburn and Broken River Catchments. GBCMA, Shepparton. Funding for this booklet was provided through the Natural Heritage Trust (NHT), the National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality and the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority. First printed 2004. Copyright of photographs remains with the photographers mentioned in the text. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance, but the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority and the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purpose and therefore disclaim all liability for any error; loss or other consequence which may arise from your relying on any information in this publication. Authors Debbie Colbourne (Department of Sustainability and Environment [DSE]), Ann Jelinek, (Ecoviews Pty Ltd), Doug Robinson (Trust for Nature and DSE), Steve Smith (DSE) and Kate Stothers (Department of Primary Industries [DPI]). Acknowledgements This booklet was prepared with assistance from: Jerry Alexander (DSE); Kate Bell, Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority (GBCMA); Andrew Bennett, Deakin University; Sue Berwick (DSE); Marion Howell; Lisa McKenzie, Impress Publicity; Rebecca Nicoll (GBCMA); Bill O’Connor (DSE), Stephen Platt (DSE); Helen Repacholi (DPI); Melody Serena, Australian Platypus Conservancy; Jenny Wilson (DSE). Special thanks to the following people for supplying photographs or contributing to parts of the text: Brad Costin, Ross Field, Julie Flack, Bertram Lobert, Lindy Lumsden, Peter Marriott, Peter Mitchell, Tim New, Bill O’Connor, Colin Officer, Peter Robertson, Lance Williams, Alan Yen. ISBN: Ringbound - (1-920742-07-7) and CD-Rom - (1-920742-08-5) 22 ContentsContents 1.