Of Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bcsfazine #320

• EVENTS • LETTERS • FEATURES • MOVIES • REVIEWS • BOOKS • LISTINGS • NEWS • Vol. 28 Issue 1 Number 320 January 2000 $2.50 THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE WEST COAST SCIENCE FICTION ASSOCIATION VCON25 in 2000 Mammals Beware! SF Book Review Movie Mania May 26-28 2000 Dr. Media WCSFA Memberships WCSFActivities New ...................................... $26.00 New Family .......................... $32.00 F.R.E.D. - Every Friday BCSFAzine at FRED! Pristine, mint condition cop- Renewal ................................ $25.00 The weekly gathering of BCSFAns and all ies are available at FRED. Call Steve to let him know Family (2 Votes) ................... $31.00 others interested in joining us for an evening you wish to pick up your copy. (Above prices includes subscription to of conversation and relaxation, with pool Discount Movie Nights. BCSFAzine. Please e-mail table option. At the Burrard Motor Inn $2.00 Tuesdays are back! When? The second Tuesday [email protected] if you wish to oposite St. Paul’s Hospital (Downtown Van- of the month (Sep. 14th) at 6:30 pm. The place being receive the magazine electronically.) couver) 6 blocks south of Burrard Skytrain New West Cinema at #229 - 555 Sixth Street, New Make checks payable to WCSFA Station. 3 blocks west of Granville (where Westminster. Meet in front of the Box Office at the (West Coast Science Fiction many buses run). #22 Knight/McDonald above time and we’ll decide on which movie, where to Association) bus along Burrard. Begins 8:00pm. On the do coffee and in which order. Send cheques to: WCSFA Friday before long weekends, FRED will Annual Christmas Dinner December 11th, 7:00 pm #110-1855 West 2nd Ave. -

The End of Eternity Ebooks Free This Stand-Alone Novel Is Widely Regarded As Asimov's Best Science Fiction Novel

The End Of Eternity Ebooks Free This stand-alone novel is widely regarded as Asimov's best science fiction novel. Andrew Harlan is an Eternal, a member of the elite of the future. One of the few who live in Eternity, a location outside of place and time, Harlan's job is to create carefully controlled and enacted Reality Changes. These Changes are small, exactingly calculated shifts in the course of history, made for the benefit of humankind. Though each Change has been made for the greater good, there are also always costs. During one of his assignments, Harlan meets and falls in love with Noÿs Lambert, a woman who lives in real time and space. Then Harlan learns that Noÿs will cease to exist after the next Change, and he risks everything to sneak her into Eternity. Audio CD Publisher: Blackstone Audiobooks (January 1, 2010) Language: English ISBN-10: 0792760581 ISBN-13: 978-0792760580 Shipping Weight: 8.3 ounces Average Customer Review: 4.5 out of 5 stars 306 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #2,919,901 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #4 in Books > Books on CD > Authors, A-Z > ( A ) > Asimov, Isaac #1732 in Books > Books on CD > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Science Fiction #2045 in Books > Books on CD > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Fantasy Praise for The End of Eternity:“His most effective piece of work. Asimov’s exemplary clarity in plotting is precisely suited to the material at hand. Asimov’s engagement with the present is clearer here than in his other works, as is his engagement with the human.â€Â--Locus“By literary standards, this tale of time travel from the 95th century is generally rated Asimov’s best.â€Â--Entertainment Weekly“Asimov’s flirtation with the tropes employed by A. -

Postgraduate English: Issue 09

Boyd Postgraduate English: Issue 09 Postgraduate English www.dur.ac.uk/postgraduate.english ISSN 1756-9761 Issue 09 March 2004 Editors: Anita O’Connell and Michael Huxtable Does Anyone Have the Right Time Please? A New Perspective on Time Travel Narratives in the 1950s & 1960s Sinead Boyd* * Lancaster University ISSN 1756-9761 1 Boyd Postgraduate English: Issue 09 Does Anyone Have the Right Time Please? A New Perspective on Time Travel Narratives in the 1950s & 1960s Sinead Boyd Lancaster University Postgraduate English, Issue 09, March 2004 Introduction: Searching for science When considering the term science fiction some useful questions to ask are: what is the ‘science’ in science fiction? Is it a sort of science that as readers, we can trust? Are there any facts hidden behind the fiction? Also, what would the ‘fiction’ be without the science? It is a widely held belief that genre fiction (which is to include science fiction) occupies a separate cultural space to that of non- genre literature. Some for example, Patrick Parrinder, DarkoSuvin, have tried to bridge the gap by performing literary analysis on certain authors, for example, J G Ballard and Kurt Vonnegut, who themselves choose to cross the invisible boundary between genre and mainstream. However, rather than applaud the ‘literary’ nature of science fiction texts in order to afford them a place in the canon, this essay will examine science fiction within the wider cultural space of intellectual understanding and speculation. Taking as its central theme the subject of time travel in both non-fiction and fiction, this essay aims to illustrate the interconnectedness of science, culture and literature. -

Thyme #34 ☆ Ohhh...), for a Screening of the Excellent Bladerunner, the "Harrison Ford Always Lets 'Em Rough Him up a Bit Before He Blows ’Em Open" Show

Australia Post #vbh2625 is produced by Roger Weddall, of 79 Bell Street, Fitzroy 3065, AUSTRALIA telephone (03) 417 1841. It is available for news or other information, or for MONEY - at the following rates: AUSTRALIA: 10 issues for $5; NORTH AMERICA-NEW ZEALAND: 10 issues for fl0; EUROPE: 10 issues for £5, DM20, or a letter of interest (I'm rather partial to "A”, myself).ALL OVERSEAS COPIES ARE SENT via AIRMAIL. —:-------------------- Agents: Europe: Joseph Nicholas, 22 Denbigh St., Pimlico, London SW1V 2ER, U.K. North Americas Jerry Kaufman, 4326 Winslow Place North, Seattle, WA 98103, U.S.A. New Zealand: Nigel Rowe, 24 Beulah Avenue, Rothesay Bay, Auckland 10. Don't forget, a big, silver cross next to your name means that, if you want to keep on seeing copies of this thing, you'd better DO SOMETHING£ ttttttt+ttttttttttttftttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttftttttttttttti'ttt+tfttTT Just When You Thought It Was Safe To Go Back To Perth - SWANCON 9a a con report by Craig Milton "If you want a good description and definition of anarchy, go no further than the Goon Show at Swancon 9a. Swancon 9a if you weren't aware of it was a convention cum birthday party for Craig Hilton (Rat artist and idiot (Eccles) extraordinaire!). I had the dubious pleasure of being the GoH - I say dubious probably due to the fact that I was co-organiser of the event. This probably accounts for 2/3 of the anarchy!" Julia Bateman Don't Stop! Don't Stop!... SWANCON 9a (a microlaxacon) "Swancon 9a?" you ask. Furthermore: "What Is It?" "isn’t it just too much of a good thing?" and "Why wasn't I invited?" Let me set your minds at rest. -

Program Book

Jeffrey A. Ca’ver. author of the widely praised THE INFINITY "The premier horror writer of his or any generation." I INK. has ■flun'cd ■•••• th a stunning new novel set at the un’ikely — Stephen King crossroads of dance. mus'C. and interstellar war. F ' J 4 0-312-93587 0/S15.95/352 pages 0-312 94381-4/S18-95/384 pages Nationally distributed by St. Martin's Press TOR Nationally distributed by St. Martin's Press TOR AVAILABLE IN PAPERBACK IN MAY 1987 HORROR iW.'. "Tough and sensitive, comical ana evocative. ’ This may well be a book that today's readers will pass along ‘o JLDiTHlAPP JUDITH TAPP their children in 20 years' time." —NEWS DAY "Fantasy in the grand tradition*" 3®' — ’HE DENVER POST Till' IKXSP* Illi. lAkkA nn iiecKDOTiE mtcos i dilogy "This whole series is highly recommended.' -SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW COMING IN MAY— THE HOUNDS OFGOD Judith Tarr Volume Three of THE HOUND AND THE FALCON TRILOGY 54937-6/S2.95/304 pages 55605 4/53.50/352 pages Naticrol'y disk outed by Warner Publisher Sc-vces and St. Martin’s Press Nationally distributed by Warner Publisher TOR Ser vices and St. Marlin's Press Boskone XXIV February 13-15, 1987 Guest of Honor: C.J. Cherryh Official Artist: Barclay Shaw Special Guest: Tom Clareson Contents A Note From the Editor_____________ _2 Art Show____________________ ______ 31 Chairman’s Greetings______________ _2 Hucksters’ Room______________ ______ 32 Boskone XXIV Committee List_______ _2 Games_____________________________ 33 Our Weapons Policy_________________6 Dragonslair__________________ ______ 33 Official Notices___________________ _6 Babysitting__________________ ______ 33 Guest of Honor - C.J. -

Fossil Hominids FAQ In

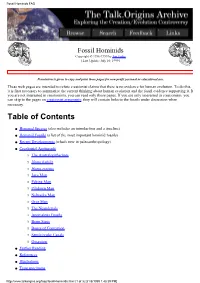

Fossil Hominids FAQ Fossil Hominids Copyright © 1996-1999 by Jim Foley [Last Update: July 10, 1999] Permission is given to copy and print these pages for non-profit personal or educational use. These web pages are intended to refute creationist claims that there is no evidence for human evolution. To do this, it is first necessary to summarize the current thinking about human evolution and the fossil evidence supporting it. If you are not interested in creationism, you can read only those pages. If you are only interested in creationism, you can skip to the pages on creationist arguments; they will contain links to the fossils under discussion when necessary. Table of Contents ● Hominid Species (also includes an introduction and a timeline) ● Hominid Fossils (a list of the most important hominid fossils) ● Recent Developments (what's new in paleoanthropology) ● Creationist Arguments ❍ The Australopithecines ❍ Homo habilis ❍ Homo erectus ❍ Java Man ❍ Peking Man ❍ Piltdown Man ❍ Nebraska Man ❍ Orce Man ❍ The Neandertals ❍ Anomalous Fossils ❍ Brain Sizes ❍ Bones of Contention ❍ Semicircular Canals ❍ Overview ● Further Reading ● References ● Illustrations ● Type specimens http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/fossil-hominids.html (1 of 3) [31/8/1999 1:48:39 PM] Fossil Hominids FAQ ● Biographies ● What's New? ● Feedback ● Other Links ● Fiction ● Humor ● Crackpots ● Misquotes ● About these pages This site will be updated on a regular basis. Contact the author ([email protected]) with corrections, criticisms, suggestions for further topics, or to be notified of future versions. The FAQ can be found in the talk.origins archives on the Internet at: http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/fossil-hominids.html (Web version) ftp://ftp.ics.uci.edu/pub/origins/fossil-hominids (text version) Thanks to those who have reviewed or made comments on the FAQ, including Randy Skelton, Marc Anderson, Mike Fisk, Tom Scharle, Ralph Holloway, Jim Oliver, Todd Koetje, Debra McKay, Jenny Hutchison, Glen Kuban, Colin Groves, and Alex Duncan. -

CHAPTER I Isaac Asimov

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA, LETRAS Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN CARRERA DE LENGUA Y LITERATURA INGLESA "Isaac Asimov and the Golden Age of Science Fiction: A Study in Terms of his Contribution to the Genre” Trabajo de graduación previo a la obtención de un título de Licenciado en Ciencias de la Educación en Lengua y Literatura Inglesa AUTOR: ISMAEL ALEJANDRO OCHOA COBOS CI. 0106650153 DIRECTOR: FABIÁN DARÍO RODAS PACHECO CI. 0101867703 CUENCA-ECUADOR 2017 Universidad de Cuenca RESUMEN Este trabajo investigativo trata de la vida y la obra literaria de una persona extraordinaria: Isaac Asimov. Su vida fue la de un genio que aprendió a leer y escribir por sí mismo y que escribió su primer relato a la edad de once años. Su producción literaria abarca diversos campos del conocimiento: ciencia pura, religión, humanismo, ecología y, especialmente, el campo de la ciencia ficción. Este último, género literario al cual él contribuyó a darle la forma definitiva que tiene en la actualidad. Concomitantemente, entonces, esta investigación cubre la historia de la ciencia ficción como género literario, desde sus manifestaciones más tempranas hace miles de años, hasta las absorbentes producciones audiovisuales que cautivan la atención tanto de niños como adultos hoy en día. Por este motivo, los contenidos de esta tesis también incluyen una descripción, llena de abundantes ejemplos, sobre las características que este género ha adquirido en nuestros días. Entre los numerosos trabajos de Asimov que se encuentran ligados a la ciencia ficción, dos series de libros aparecen como los más importantes. Se trata de sus series Fundación y Robots. -

Fantasy Review V008n05 (1985

$5776 Theodore Sturgeon 1918-1985 A MAJOR NEW MEDIEVAL FANTASY from Bluejay Books "Have you ever found yourself-and all her future readers—a treasure!" —Katherine Kurtz, author of Camber the Heretic "An exciting tale, well told, with a great deal of Originality." —POUI Anderson > THE NEW BIG NAME IN FANTASY A BLUEJAY INTERNATIONAL Bluejay Books Inc. James Frenkel, Publisher EDITION HARDCOVER $14.95 130 w. 42nd Street, Suite 514 Subscribe to the Bluejay Flyer New York, NY 10036 Distributed by St. Martin’s Press, inc. Write for a free catalog Dept. FS-5 Canadian distribution by Methuen of Canada Theodore Sturgeon 1918-1985 I Winner of Balrog and World Fantasy Awards, Hugo Finalist (Formerly Fantasy Newsletter) Founded by Paul C. Allen Volume 8, No. 5, Whole #79 May, 1985, ISSN 0747-234X Editor-in-Chief: Robert A. Collins Business & Accounts: Catherine Fischer Production Assistants Martin A. Schneider Carol Csomay Heather Manning Contributing Editors: FHtz Leiber Karl Edward Wagner Douglas E. Winter Steve oc Cornelia Theys Arnie Fenner Timothy Robert Sullivan Somtow Sucharitkul Published monthly by Florida Atlantic University through the Division of Con- tinuing Education, Melvin Hall, Dean; and with the cooperation of the Science Fiction Research Association, Donald M. Hassler, President. Single copy $2.75. Back issues, $2.50. Yearly subscriptions: $20 second class U. S. $25 second class Canada COLUMNS & FEATURES: $30 first class U.S., Canada $30 surface to Europe, Asia Theodore Sturgeon: A Biographical Sketch $45 airmail to Europe By BOB COLLINS page 6 $50 airmail to Asia Display advertising rates, based upon I Remember Ted current circulation of 3000 copies, esti - mated readership of 10,000, upon re- By JAMES GUNN page 7 quest. -

The Science Fiction Handbook

The Science Fiction Handbook M. Keith Booker and Anne-Marie Thomas A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication The Science Fiction Handbook The Science Fiction Handbook M. Keith Booker and Anne-Marie Thomas A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition first published 2009 # 2009 by M. Keith Booker and Anne-Marie Thomas Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148–5020, USA For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book, please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley- blackwell. The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. -

St.Louiscon Report St.Louiscon, the 27Th World Science Fiction Convention, Held Over the August 28-Sept

No. 5 October 1969 St.Louiscon Report St.Louiscon, the 27th World Science Fiction Convention, held over the August 28-Sept. 1 Labor Day weekend, fulfilled its promise of being the largest convention the science fiction world has ever known. Some of the staggering statistics include registration at 1919, attendance officially posted at 1534, and auction income (gross) of $6,800. Not only was this the largest convention to date, it was also the longest. Although official registration didn't begin until noon on Thursday, par tying began Tuesday evening in the con committee suite; and the parties continued through the following Tuesday night. Paid attendance at the banquet was 660 and would have been more except that tickets were only sold until Saturday noon. Hugo Awards BEST NOVEL: Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner (accepted by Gordon Dick son) BEST NOVELLA: Nightwings by Robert Silverberg BEST NOVELETTE: The Sharing of Flesh by Poul Anderson BEST SHORT STORY: The Beast That Shouted Love by Harlan Ellison BEST DRAMATIC PRESENTATION: 2001: A Space Odyssey (accepted for Arthur C. Clarke by Dave Kyle) BEST PROFESSIONAL MAGAZINE: Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction BEST PROFESSIONAL ARTIST: Jack Gaughan BEST FAN ARTIST: Vaughn Bode BEST FANZINE: Psychotic (accepted for Dick Geis by Bruce Pelz) BEST FAN WRITER: Harry Warner Jr. (accepted by Bill Evans) SPECIAL AWARD: presented to astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins "for the best moon landing ever" (accepted by Hal Clement) Other Awards BIG HEART AWARD: presented to Harry Warner Jr. by Forry Ackerman (ac cepted by Bob Bloch) FIRST FANDOM AWARD: presented to Murray Leinster by last year's winner, Jack Williamson (accepted by Judy Lynn Benjamin) At the banquet Lester Del Rey presented a moving eulogy to Willy Bidding for the 1971 convention provided more of a contest with the Ley, in which he paid tribute to Willy's contributions to man's landing choice between Boston and Washington. -

Die Hugo Awards 1985-2000

LESEPROBE HARDY KETTLITZ DIE HUGO AWARDS 1985 – 2000 MEMORANDA ist ein Imprint des Golkonda Verlages und wird herausgegeben von Hardy Kettlitz. Der Autor bedankt sich bei Christian Hoffmann und Hannes Riffel für die tatkräftige Unterstützung. Hardy Kettlitz Die Hugo Awards 1985–2000 © 2016 by Hardy Kettlitz Mit freundlicher Genehmigung des Autors © dieser Ausgabe 2016 by Golkonda Verlag GmbH Alle Rechte vorbehalten Lektorat: Hannes Riffel Korrektur: Horst Illmer & Inger Banse Gestaltung: s.BENeš [www.benswerk.wordpress.com] Satz: Hardy Kettlitz Druck: Schaltungsdienst Lange Golkonda Verlag Charlottenstraße 36 12683 Berlin [email protected] www.golkonda-verlag.de www.memoranda.eu ISBN: 978-3-944720-73-9 Inhalt Inhalt Vorwort 7 Anmerkungen 10 Abkürzungen 14 Die Hugo Awards 1985–2000 1985 19 1986 34 1987 50 1988 65 1989 80 1990 94 1991 108 1992 122 1993 136 1994 154 1995 168 1996 183 1997 198 1998 210 1999 224 2000 238 Anhang Der Retro-Hugo 255 1946 256 Index 268 5 Vorwort Vorwort Wenn Sie den Titel dieses Buches betrachten, dann werden Sie feststel- len, dass es einen Zeitraum von nur sechzehn Jahren umfasst. Im ersten Band hingegen waren die Hugo Awards von 31 Jahren enthalten, und vielleicht werden Sie sich fragen, warum das so ist. Das kam so: Mein ursprünglicher Gedanke war, den Zeitraum von 1953 bis heute, also gut sechzig Jahre, einfach durch zwei zu teilen und alle Gewinner der Hugo Awards demzufolge in zwei Bänden vorzustel- len. Mein fataler Denkfehler wurde mir leider erst bewusst, als der erste Band bereits im Druck war. Wie Sie beim Durchblättern dieses Buches feststellen können, gab es ab den späten 1980er Jahren deutlich mehr Rubriken, in denen Hugos verliehen wurden, als in den Jahrzehnten zuvor. -

Oil, Scarcity, Limit Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2014 Retrofutures and Petrofutures: Oil, Scarcity, Limit Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. "Retrofutures and Petrofutures: Oil, Scarcity, Limit," in Oil Culture. Eds. Ross Barrett nda Daniel Worden. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014. Publisher link. © 2014 University of Minnesota Press. Used with permission. 17 Retrofutures and Petrofutures Oil, Scarcity, Limit Gerry Canavan Fredric Jameson has written that “in our time . the world system . is a being of such enormous complexity that it can only be mapped indirectly, by way of a simpler object that stands as its allegorical interpretant.”1 In this chapter, I offer up oil, and oil capitalism, as one such interpretant for the historical world-system as a whole—and further offer up science fiction as a means to register the different meanings of “oil” that are available in different historical moments. Oil’s ubiquity and centrality within contemporary consumer capitalism suggests it as an especially useful allegorical interpretant. Oil is extremely local—as local as your corner gas station, as your car’s gas tank—but at the same time it is the token of a vast spatiotemporal network of seemingly autonomous actors. In his story “The Petrol Pump,” Italo Calvino evokes this immense, even sublime, interactivity: “As I fill my tank at the self-service station a bubble of gas swells up in a black lake buried beneath the Persian Gulf, an emir silently raises hands hidden in wide white sleeves, and folds them on his chest, in a skyscraper an Exxon computer is crunching numbers, far out to sea a cargo fleet gets the order to change course.”2 To Calvino’s totalizing vision of oil’s global interconnectedness we might add not only the million-year geological time scale necessary for oil’s creation, but also the immeasurably complex flows of money, power, and technology that make the current global economy, and U.S.