Embracing Co-Creation Thinking in Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ireland's Experience Economy

Ireland’s Experience Economy 2021 #yourexperienceeconomy 2 Ireland’s Experience Economy 1 Ireland’s Experience Economy 1 Experience Economy by the numbers 2 Ireland’s Our campaign 4 Campaign purpose 4 Defining the Experience Economy 5 Experience Social and economic contribution 6 Sustainability and a shared island 6 Policy asks 7 Economy 1 Bouncing back 9 2 Putting people first 13 3 Fire powering product, marketing and digitalisation 17 With a landscape, surrounded by an outstanding Calls to action 20 coastline, diverse and dramatic, a haunting history steeped in ancient traditions, literature, folklore and music fused culture, Ireland has all the raw materials for an exceptional experience. This amazing place, famous for its welcome, is backed by thousands of businesses and hundreds of thousands of people that power it. Our world-renowned hotels, fantastic festivals, the fame of sporting occasions, our rich provenance in food and drink, the ceremonies marking our culture and way of living, our campaign global connectivity join forces to create experiences unique to the island of Ireland. The Experience Economy is part of Ibec’s Reboot and Reimagine campaign to shape a better and sustainable future for Ireland. This is the Experience Economy and more than meets the eye. The Reboot and Reimagine campaign provides a range of solutions that cover the enormity and breadth of the challenges posed by the pandemic. It outlines thematic policy actions across engagement and crisis management, getting people back to work, fiscal policy and stimulus measures, responding to Brexit and reimaging a better Ireland. With courage and commitment from Government, the business community and the public, the Reboot and Reimagine campaign can chart not simply a recovery for society and the economy, but one which will deliver a more sustainable future for all. -

Application of Brand-Centered Experience Design in the Transformation of Traditional Enterprises

Frontiers in Art Research ISSN 2618-1568 Vol. 2, Issue 6: 71-82, DOI: 10.25236/FAR.2020.020613 Application of Brand-centered Experience Design In the Transformation of Traditional Enterprises Yubo Zhang*, Min Lin School of innovation and design, The Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, Guangzhou, 510260, China *Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT. After 40 years of reform and opening up, China has become the world’s second largest economy. With the rapid economic development, local traditional enterprises have gradually paid attention to and realized the importance of user experience for enterprise transformation. However, every traditional enterprise must consider how to integrate user experience into the enterprise's existing model and give play to the market value of user experience. This paper explores the relationship between brand, experience and design. And, combined with brand positioning theory, behavioral economics prospect theory and experience model of design psychology, this paper proposes a brand-experience-design integration strategy model, which has been initially verified in corporate practice. KEYWORDS: Experience design; Brand; Integration 1. Introduction After 40 years of reform and opening up, China has become the world’s second largest economy. Economic development and technological progress have affected people’s needs and desires and consumers’ consumption patterns accordingly. Economic development has moved from the past agricultural economy, industrial economy, and service economy to the current experience economy. The so-called experience economy is an economic form in which goods and services are used as carriers to meet people’s ever-increasing spiritual needs, so that consumers can get emotional and self-realization value satisfaction and enjoyment. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Architecture in the Experience Economy: the Catalog Showroom and Best Products Company a Di

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Architecture in the Experience Economy: The Catalog Showroom and Best Products Company A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Christina Bernadette Gray 2019 © Copyright by Christina Bernadette Gray 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Architecture in the Experience Economy: The Catalog Showroom and Best Products Company by Christina Bernadette Gray Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Sylvia Lavin, Chair Although it is often assumed that production must logically precede consumption, the development of postmodern architecture complicates this narrative. The development of postmodern architecture undermined established structures by centralizing the role of consumption and the consumer. This dissertation examines ways in which various conservative trends pushed the consumer closer toward production. These changes ushered in the experience economy of which Best Products Company and the broader catalog showroom phenomena were particularly emblematic. Drawing on these changes within the history of retail architecture, this dissertation sets out to explore how architecture emerged into the postmodern period as a box, a malleable shell that was increasingly being invaded and overturned by a powerful consumer. ii This dissertation of Christina Bernadette Gray is approved. Dana Cuff Michael Osman Debora Silverman Sylvia Lavin, Committee Chair University of California, Los -

Teaching Leadership in the Experience Economy Paradigm

Journal of Leadership Education DOI: 10.12806/V14/I4/I3 Special 2015 Teaching Leadership in the Experience Economy Paradigm Lori L. Moore Associate Professor Texas A&M University Jacklyn A. Bruce Associate Professor North Carolina State University Introduction Anyone involved in higher education today faces challenges. We are being asked to provide the best, most relevant education for today’s diverse student population while facing increasing budget cuts, and at the same time assess and demonstrate the student learning taking place. The argument can be made that students are an educator’s customers. It can also be argued that leadership educators strive to engage students (customers) through the various teaching strategies they employ within their programs, classrooms, or other contexts. In a world with greater emphasis being put on the bottom line of education, we cannot deny the importance of recruiting happy customers (students) who continue to return to our programs. For leadership educators, this means we must meet the needs of our “customers” without diluting or devaluing the educational process and intended outcomes of higher education. Students today have been described as consumer oriented, entertainment oriented, and entitled (Taylor, 2006). Taylor (2006) noted, Any topic, class, or field that cannot demonstrate its utility and meaning to each student will be suspect…The ability of each instructor to articulate a rationale for the necessity of their subject based on real world application is a necessary but not sufficient prerequisite for students to develop such necessary applications and subsequent value. Pedagogical activities must be available so each student can apply information to her/his own past, present, and future life. -

The Nordic Approach to the Experience Economy Does It Make Sense? Bille, Trine

The Nordic Approach to the Experience Economy Does It Make Sense? Bille, Trine Document Version Final published version Publication date: 2010 License CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Bille, T. (2010). The Nordic Approach to the Experience Economy: Does It Make Sense? imagine.. CBS. Creative Encounters Working Paper No. 44 Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Creativity at Work: The Nordic approach to the Experience Economy – does it make sense? By Trine Bille, Associate Professor, Ph.D., Copenhagen Business School, Department of Innovation and Organizational Economics January 2010 Page 1 / 24 Creative Encounters Working Paper #44 Abstract: This paper discusses the concept of the experience economy in a Nordic context and shows how the Nordic version of the concept has come about from a mix of three different approaches and theories. Besides, the Nordic definition links the experience economy closely with cultural activities. In the Nordic countries the experience economy has been developed in a political context and it is apparently a popular development policy for local government authorities and regions. This paper discusses the Nordic definition of experience economy and questions if it makes any sense. -

Gaps, Inconsistencies, Contradictions and Future Research Directions Within Customer Experience Management

Proceedings of The 24th World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics (WMSCI 2020) Systematic Literature Overview: Gaps, Inconsistencies, Contradictions and Future Research Directions within Customer Experience Management Gundars KOKINS Faculty of Engineering Economics and Management, Riga Technical University Riga, Latvia Anita STRAUJUMA Faculty of Engineering Economics and Management, Riga Technical University Riga, Latvia ABSTRACT oriented/driven” marketing as the replacement for the already outdated “goods -oriented marketing”, the research of The topic of Customer Experience Management has been customer experience turned to establishing processes, actively debated over the last 25 years, however, marketing measurements, tools and methods of mapping, designing and practitioners and theorists still don’t seem to agree on the measuring customer experiences in organizations in the dimensions, definitions and nature of the construct. New second half of the 2000’s. emerging technologies such as wearable gadgets, IoT and natural language processing constantly offer new frontiers in However, despite this construct growing larger and wider, both practical and theoretical research. The purpose of this papers published in the past few years are pointing out the literature overview is to identify the various research topics, lack of the most basic and fundamental of research questions issues and criticism within previous research and further having been answered and established within “customer research directions suggested, to identify reoccurring topics experience management” construct – such as definition, and points of issue, gaps within the theory or empirical proof, context, dimensions and foundation [3]. Some even question and be able to determine whether those points are addressed the novelty and independence of this research stream, in later research. -

The Re-Emergence of the Experience Economy MAKE CONTACT: the RE-EMERGENCE of the EXPERIENCE ECONOMY

MAKE CONTACT The re-emergence of the experience economy MAKE CONTACT: THE RE-EMERGENCE OF THE EXPERIENCE ECONOMY INTRO & METHODOLOGY WHAT HAPPENS NOW? We are at a turning point in human history. The events of VMG FUTURE OF SUPPORTING SOURCES: 2020 – COVID-19, social and political turmoil, disinformation – have challenged us beyond measure. Through all of this EXPERIENCES STUDY: VMG Youth in Pandemic chaos and uncertainty, experiences and connections have not Research Series: March-Sept been on hold, they’ve just looked different. 8 Qualitative IDIs with Event & Experience Experts 2020, n=10,000+ Global youth We’re about to reemerge into a cultural renaissance with respondents energy unlike anything seen before. So what happens to the 3 Qualitative Inputs from experience economy now? Experiential Design Grad Students VMG’s Proprietary Insights Communities: VICE Voices & In this report, we’ll glimpse into the future as seen through Online Quantitative Survey Mad Chatter the lens of young people - young people who have evolved, with 1,069 Respondents envisioned, and changed the world during such a pivotal time. Markets: US & UK We look at a newly developed marriage between consumer Demographics: 47% Men, 50% Women, identity and experiences, the intentionality with which young people will partake in events and seek out new experiences, 3% Non-binary and the key shifts in consumer perspective that will steer us Generations: 70% Gen Z & Millennial into the next era of culture and the future of the Field Dates: Jan-Feb 2021 experiential economy. 2 MAKE CONTACT: THE RE-EMERGENCE OF THE EXPERIENCE ECONOMY A RESURGENCE OF IN-PERSON EXPERIENCES AFTER MORE THAN A In-person experiences are about to return with even greater YEAR OF LIMITED vivacity and young people are bracing themselves for their IN-PERSON EVENTS, PENT return to the physical world. -

A Comprehensive Socio-Economic Model of the Experience Economy: the Territorial Stage

WORKING PAPER 9 – 2014/E THE CIRCULATION OF WEALTH A COMPREHENSIVE SOCIO-ECONOMIC MODEL OF THE EXPERIENCE ECONOMY: THE TERRITORIAL STAGE Guex Delphine and Olivier Crevoisier Authors Guex Delphine and Olivier Crevoisier Delphine Guex is a PhD student at the University of Neuchâtel, at the Institute of Sociology, and Member of the Research Group on Territorial Economy (GRET). Her research interests: tourism, his- tory, economic sociology of communication, cultural resources, presential economy. [email protected] Olivier Crevoisier is Professor of Territorial Economy at the Institute of Sociology and Director of the Research Group on Territorial Economy (GRET) at the University of Neuchâtel. He is also a mem- ber of the European Research Group on Innovative Milieux (GREMI). Research interests: innovative milieus, finance industry and cultural resources. [email protected] © 2014 by the authors ISSN : 1662-744X La reproduction, transmission ou traduction de tout ou partie de cette publication est autorisée pour des activités à but non lucratif ou pour l’enseignement et la recherche. Dans les autres cas, la permission de la MAPS est requise. Contact : MAPS - Maison d’analyse des processus sociaux Faubourg de l’Hôpital 27 CH - 2000 Neuchâtel Tél. +41 32 718 39 34 www2.unine.ch/maps [email protected] Abstract This paper deals with the economic dimension of the experience economy, i.e. how economic value is created between customers and producers and is articulated to monetary transactions. After discussing the Pine & Gilmore’s metaphor of stage and concept of admission fees, we propose the model of the Territorial Stage constituted by two elements. -

The Future of Car Dealerships: Omnichannel Sales in the Experience Economy, B.S., Management & Marketing, April, 2018

Skinner, Cameron, J., The Future of Car Dealerships: Omnichannel Sales in the Experience Economy, B.S., Management & Marketing, April, 2018 As the demographics of the car-buying population begin to undergo dramatic shifts, the dealership model is facing unprecedented challenges to adapt to the new experience economy. Currently, only 17% of polled participants like the current car-buying model, which has negative implications for multiple industries directly and complementarily associated with dealerships. With industry disruptors, such as Tesla, challenging the quo socially, technologically, and legislatively while hedging at leaders and garnering market share, the car salesman concept (that has been in place since the inception of automobiles) is under attack. The goal of this project was to analyze the dealership model and the consumer market, and to ultimately determine the future of the car-buying process. This was accomplished by investigating consumer preferences, trends in the automobile and transportation industries, international comparisons, and the history of the dealership. All of this was taken into account to develop a sustainable, omnichannel prototype of the dealership model that benefits both the industry firms and consumers. 1 UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING HONORS THESIS The Future of Car Dealerships: Omnichannel Sales in the Experience Economy Author: Mentor: Cameron SKINNER Dr. Kent DRUMMOND A thesis presented to the University of Wyoming Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors College Laramie, Wyoming April 28, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction …………………………………………………………….3 Literature Review: Experience Economy……………………………………7 Literature Review: The Millennial Demographic………………………….10 Literature Review: Interindustry Comparison ….….………………………13 Literature Review: Industry Disruption……………………………………16 Chapter 2: Methodology and Results……………………………………………. -

The Experience Economy

PLEASE READ BEFORE PRINTING! PRINTING AND VIEWING ELECTRONIC RESERVES Printing tips: ▪ To reduce printing errors, check the “Print as Image” box, under the “Advanced” printing options. ▪ To print, select the “printer” button on the Acrobat Reader toolbar. DO NOT print using “File>Print…” in the browser menu. ▪ If an article has multiple parts, print out only one part at a time. ▪ If you experience difficulty printing, come to the Reserve desk at the Main or Science Library. Please provide the location, the course and document being accessed, the time, and a description of the problem or error message. ▪ For patrons off campus, please email or call with the information above: Main Library: [email protected] or 706-542-3256 Science Library: [email protected] or 706-542-4535 Viewing tips: ▪ The image may take a moment to load. Please scroll down or use the page down arrow keys to begin viewing this document. ▪ Use the “zoom” function to increase the size and legibility of the document on the screen. The “zoom” function is accessed by selecting the “magnifying glass” button on the Acrobat Reader toolbar. NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproduction of copyrighted material. Section 107, the “Fair Use” clause of this law, states that under certain conditions one may reproduce copyrighted material for criticism, comment, teaching and classroom use, scholarship, or research without violating the copyright of this material. Such use must be non-commercial in nature and must not impact the market for or value of the copyrighted work. -

Culture As a Developmental Driver for Italy in the Post-Covid Scenario

WEBINAR Culture as a developmental driver for Italy in the post-Covid scenario 15 May 2020 | 15.00-18.30 CEST (Paris time zone) oe.cd/culture-webinars #OECDculture REGISTER HERE Cultural and creative sectors are among the most affected by the current Coronavirus (COVID- 19) crisis also due to the extreme fragmentation of the sector where the share of small and micro firms and individual freelancers is extremely high. Although immediate support measures are necessary and urgent, this crisis also provides an important opportunity to reconsider medium- and long- term strategic options and to realign them to the shifting social, economic and technological trends. Italy in particular, whose country image is greatly associated with culture, could seize the opportunity by launching a new cycle of strategic design that involves all main stakeholders: public administration, industry, cultural players and professionals and civil society. The purpose of this webinar, organised by the OECD Venice Office for Culture and Local Development and Cultura Italiae, is to contribute to this process by convening some of the most authoritative and experienced representatives from all sectors to debate on the place of culture in Italy’s competitiveness model and the ways to foster culture-led local development in the recovery and beyond. For more information on OECD talk series on the impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis on culture: Coronavirus (COVID-19) and museums: impact, innovations and planning for post-crisis, 10 April 2020, co-organised with the International Council of Museums (ICOM) Coronavirus (COVID-19) and cultural and creative sectors: impact, policy responses and opportunities to rebound after the crisis, 17 April, co-organised with the European Creative Business Network (ECBN) ORGANISERS PARTNERS 1 AGENDA Moderator Prof. -

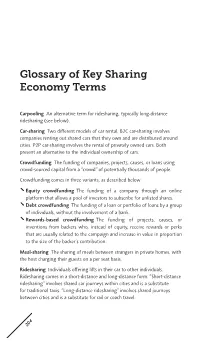

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms Carpooling An alternative term for ridesharing, typically long-distance ridesharing (see below). Car-sharing Two different models of car rental. B2C car-sharing involves companies renting out shared cars that they own and are distributed around cities. P2P car-sharing involves the rental of privately owned cars. Both present an alternative to the individual ownership of cars. Crowdfunding The funding of companies, projects, causes, or loans using crowd-sourced capital from a “crowd” of potentially thousands of people. Crowdfunding comes in three variants, as described below. Equity crowdfunding The funding of a company through an online platform that allows a pool of investors to subscribe for unlisted shares. Debt crowdfunding The funding of a loan or portfolio of loans by a group of individuals, without the involvement of a bank. Rewards-based crowdfunding The funding of projects, causes, or inventions from backers who, instead of equity, receive rewards or perks that are usually related to the campaign and increase in value in proportion to the size of the backer’s contribution. Meal-sharing The sharing of meals between strangers in private homes, with the host charging their guests on a per seat basis. Ridesharing Individuals offering lifts in their car to other individuals. Ridesharing comes in a short-distance and long-distance form. “Short-distance ridesharing” involves shared car journeys within cities and is a substitute for traditional taxis. “Long-distance ridesharing” involves shared journeys between cities and is a substitute for rail or coach travel. 204 Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms 205 Sharing economy (condensed version) The value in taking underutilized assets and making them accessible online to a community, leading to a reduced need for ownership of those assets.