Role of the Safety Regulator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Mining Eyes Mid-Term Gold Production

Research Note th 9 April 2015 Suite 5, Level 8, 99 York Street, Sydney NSW 2000 P: +61 2 9299 5001 I F: +61 2 9299 8001 [email protected] www.proactiveinvestors.com.au Northern Mining Limited Recommendation: Speculative Buy Northern Mining eyes mid-term gold production Sector: Materials o Northern Mining Ltd (ASX: NMI) is a Western Australian resource explorer that holds prime gold prospecting acreage located around Recommendation : Speculative Buy Kalgoorlie Boulder, on one of the world’s most productive gold belts. ASX Ticker Code: NMI o The acreage is known as the East Kalgoorlie Project and includes Share Price: $0.027 prospects at Blair North, Kanowna Lights and Snake Hill. 52 Week: - o Early stage exploration at Blair North has identified a structural High: $0.057 corridor that is 2 kilometres long that links the Company owned George’s Reward gold resource to an additional 1 kilometre of identified gold Low: $0.018 mineralisation at the northern end of the project area known as the Current Ordinary Northern Zone Deeps. Shares: 938.4M o Blair North forms the northern extension of the Cannon Gold Milestone shares (max): NIL Project mineralisation that is being jointly developed by Southern Gold (ASX:SAU) and Metals X (ASX:MLX), with Blair North constituting around Options: NIL 80% of the known gold strike line. Cash: $5.5M o The Cannon Gold Project currently includes shallow JORC gold Market Cap: $25.3M resources of 100,400 ounces that are contained within the southerly 20% Enterprise Value: $19.8M of the overall strike line, with the northern end of the Cannon open pit contiguous with gold resources owned by Northern Mining at the George’s Reward gold prospect. -

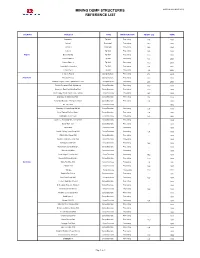

Mining Dump Structures Reference List

MINING DUMP STRUCTURES UPDATE OCTOBER 2012 REFERENCE LIST COUNTRY PROJECT TYPE MAIN FUNCTION HEIGHT [m] YEAR Luzamba Tip Wall Processing 11,4 1992 Catoca I Dump wall Processing 19,0 1995 Catoca II Dump wall Processing 16,0 1995 Catoca Tip Wall Processing 10,5 1996 Angola Escom Mining Tip Wall Processing 11,0 2002 Catoca Phase 1 Tip Wall Processing 13,6 2006 Catoca Phase 2 Tip Wall Processing 13,0 2006 Jopro 004 – Consulmet Tip Wall Processing 9,0 2007 Consulmet 2 Tip Wall Processing 9,0 2008 Veladero Project Dump structure Processing 27,8 2005 Argentina Pirquitas Project Dump structure Processing 18,0 2009 Veladero Project - Plant Expansion 85 KTPD Dump structure Processing 28,5 2009 Eastern Deepdale Pocket/Abutment Dump Structure Processing 16,0 1980 Saxonvale Raw Coal Handling Plant Dump Structure Processing 12,0 1981 Rom Hopper Walls Pacific Coal - Tarong Dump Structure Processing 19,5 1982 Boundary Hill Inpit Dump Wall - Dump Structure Processing 7,8 1982 Load Out Structure - Kangaroo Island Dump Structure Processing 6,0 1982 Mt. Tom Price Dump Structure - - 1982 Boundary Hill Inpit Dump Wall #2 Dump Structure Processing 8,0 1983 Kress Tipping Platform Stage I Dump Structure Processing 4,9 1984 Paddington Gold Project Dump Structure Processing 14,3 1984 Cork Tree Well Gold Mine Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing - 1985 Dump Wall - Cue Dump Structure Processing 8,3 1986 Telfer Mine Dump Structure Processing - 1986 Howick Colliery Temp Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing 8,4 1986 Wiluna Mine Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing - 1986 -

Telfer W with Pr 800,000 Copper Signific Resourc

4420 Newcrest Cover 04 6pp 16/9/04 9:52 AM Page 2 Telfer will be the largest gold mine in Australia, with projected annual production of more than 800,000 ounces of gold and 30,000 tonnes of copper for 24 years, positioning Newcrest as a significant and profitable Australian-based resources business. Newcrest Mining Limited Newcrest – The Sustainable Section 5 Resource Business 1 Sustainability and People 38 Section 1 Health and Safety 40 Our Results 2 Environment 42 Human Resources 43 Performance in Brief 2 Chairman’s Review 4 Section 6 ABN: 20 005 683 625 ABN: Managing Director and Corporate Governance 44 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 5 Board of Directors 45 Newcrest Senior Management 10 Corporate Governance 46 Financial Report 11 Section 7 Section 2 Concise Annual Report 2004 Financials 49 Operations 12 Directors’ Report 50 Cadia Valley Operations 14 Management Discussion and Analysis Ridgeway Gold/Copper Mine 14 of the Financial Statements 56 Cadia Hill Gold/Copper Mine 16 Statement of Financial Performance 58 Toguraci Gold Mine 19 Statement of Financial Position 59 Section 3 Statement of Cash Flows 60 Projects 22 Notes to the Concise Financial Report 61 Directors’ Declaration 68 Telfer Gold/Copper Project 24 Independent Audit Report 69 Cracow 26 Cadia East 28 Shareholder Information 70 Boddington Expansion Project 29 Five Year Summary 72 Section 4 Corporate Directory IBC Exploration 30 Strategy and Review 32 Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves 34 Newcrest Mining Limited Newcrest ABN: 20 005 683 625 Notice of Meeting Notice is hereby given that the 24th Annual General Newcrest Mining Limited Meeting will be held at the Hyatt Regency Hotel, Concise Annual Report 2004 99 Adelaide Terrace, Perth, Western Australia on Wednesday 27 October 2004 at 9.30am. -

Alacer Gold Announces Management Team

ALACER GOLD ANNOUNCES MANAGEMENT TEAM February 23, 2011, Toronto: Alacer Gold Corp (“Alacer” or the “Corporation”) [TSX: ASR] is pleased to announce the Corporation’s new management team. In determining the organizational structure for Alacer, focus was placed on ensuring the continued efficient management of its operations while delivering on the organic and strategic growth opportunities presented before the Corporation. The result is a matrix type organization where technical expertise is functionally organized to ensure best practices and coordination across the Corporation while simultaneously ensuring a solid service relationship with Alacer’s operating units to secure maximum value from its assets. The organizational chart for Alacer’s senior leadership is illustrated below along with short management biography on each executive. Edward Dowling, CEO of Alacer stated, "Alacer is fortunate to draw from the deep pool of management skills and experience provided by its predecessor companies. The leadership team assembled is comparable to the best in the industry and has a proven track record of success. Alacer is well positioned to create value as a leading intermediate gold producer and to deliver on future growth.” Page 1 of 5 Edward Dowling – Chief Executive Officer BSc, MSc, PhD Mr. Dowling joined Alacer (formerly Anatolia Minerals) in early 2008 after a successful tenure as CEO and President of Meridian Gold Inc. Mr. Dowling has 30 years of mining experience in various leadership capacities. Mr. Dowling is recognized in the industry for his ability to assemble and motivate teams of people to tackle and deliver challenging projects for creation of long-term value. Grant Dyker – Executive Vice President, Finance BBus, ACA Mr. -

A Structural Examination of the Telfer Gold-Copper Deposit And

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Hewson, Simon Andrew John (1996) A structural examination of the Telfer gold-copper deposit and surrounding region, northwest Western Australia: the role of polyphase orogenic deformation in ore-deposit development and implications for exploration. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/27718/ If you believe that this work constitutes a copyright infringement, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/27718/ A Structural Examination of the Telfer Gold-Copper Deposit and Surrounding Region. northwest Western Australia: The Role of Polyphase Orogenic Deformation in Ore-deposit Development and Implications for Exploration. VOLUME 1 Thesis submitted by Simon Andrew John HEWSON BSc (Hans) (Curtin) in October, 1996 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Earth Sciences at James Cook University of North Queensland. I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that the following restriction placed by me on access to this thesis will not extend beyond three years from the date on which the thesis is submitted to the University. I wish that access to this thesis not to be permitted for a period of three years. After this period has elapsed I understand that James Cook University of North Queensland will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other photographic means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: " In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely para-phrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which I have obtained from it. -

For Personal Use Only

To: Company Announcements Office LEVEL 9 600 ST KILDA ROAD MELBOURNE From: Francesca Lee VICTORIA 3004 AUSTRALIA Date: 13 February 2015 PO BOX 6213 Subject: Annual Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves ST KILDA ROAD CENTRAL Statement Explanatory Notes MELBOURNE 8008 T +613 9522 5333 F +613 9525 2996 www.newcrest.com.au Please find attached Newcrest Mining Limited’s Annual Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves Statement Explanatory Notes for the year ended 31 December 2014, for immediate release to the market. Yours sincerely Francesca Lee Company Secretary For personal use only A MEMBER OF THE NEWCREST MINING GROUP ABN 20 005 683 625 Explanatory Notes Newcrest Mining 13 February 2015 Annual Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves Statement – 31 December 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Newcrest Mining Limited has updated its Mineral Resource and Ore Reserve estimates for the twelve month period ending 31 December 2014 and for this purpose, has completed a detailed review of all production sources. The review has taken into account updated long term metal price, foreign exchange and cost assumptions, and mining and metallurgy performance to inform cut-off grades and physical mining parameters. This has resulted in the most marginal ounces being removed from the portfolio and these are reflected in changes to Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves. Group Mineral Resources As at 31 December 2014, Group Mineral Resources are estimated to contain 140 million ounces of gold, 20 million tonnes of copper and 130 million ounces of silver. This represents a decrease of approximately 8 million ounces of gold (~5%), 0.4 million tonnes of copper (~2%) and 1 million ounces of silver (~1%), compared with the estimate as at 31 December 2013. -

Telfer Project, Expansion of Telfer Gold Mine, Great Sandy Desert

Telfer Project, Expansion of Telfer Gold Mine, Great Sandy Desert Newcrest Mining Limited Report and recommendations of the Environmental Protection Authority Environmental Protection Authority Perth, Western Australia Bulletin 1059 August 2002 ISBN. 0 7307 6694 2 ISSN. 1030 - 0120 Assessment No. 1445 Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND......................................................1 2. THE PROPOSAL.............................................................................................2 3. CONSULTATION............................................................................................7 4. RELEVANT ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS ..............................................7 4.1 FLORA AND FAUNA ......................................................................................7 4.2 DEWATERING AND BOREFIELD OPERATIONS..................................................8 4.3 GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS.......................................................................9 4.4 ACID MINE DRAINAGE...............................................................................10 4.5 MINE CLOSURE ..........................................................................................10 5. CONDITIONS AND COMMITMENTS .......................................................11 6. CONCLUSIONS.............................................................................................12 7. RECOMMENDATIONS................................................................................12 Table Table 1: Summary of key proposal characteristics.................................................6 -

2019 Annual Report FORGING a STRONGER NEWCREST

2019 Annual Report FORGING A STRONGER NEWCREST The success of FY19 reflects the enormous amount of effort applied by our people towards delivering on our commitments and our potential. SANDEEP BISWAS MANAGING DIRECTOR AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER To be the Miner of Choice. To be the Miner of Choice for VISION our people, shareholders, host OUR communities, partners and suppliers. To safely deliver superior returns to our stakeholders from finding, developing and MISSION operating gold/copper mines. OUR NEWCREST 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 1 CONTENTS FORGING A STRONGER NEWCREST Forging a stronger Newcrest 2 Asset overview 4 Key Achievements for FY19 6 Safety & Sustainability 12 People 13 Releasing orebody potential 14 NEWCREST’S VALUE PROPOSITION Long reserve life 16 Delivering on commitments 16 Low cost production 16 Organic growth options 17 Financially robust 18 Exploration & technical capability 19 OUR COMPANY Chairman’s Report 8 Managing Director’s Review 10 The Board 20 Mineral Resources & Ore Reserves 24 Corporate Governance Statement 32 Directors’ Report 34 Financial Report 89 Corporate Directory 149 Coarse ore stockpile at Cadia, New South Wales, Australia FORGING A STRONGER NEWCREST The health and safety of our people 2 Forging a stronger is of primary importance at Newcrest. Newcrest Our clear focus remains on eliminating To achieve Newcrest’s full potential FORGING A STRONGER FORGING A STRONGER NEWCREST fatalities and life-changing injuries from for our stakeholders, our company our business, while striving to make strategy focuses on five key pillars, continual progress on reducing all injuries each with associated aspirations. and health impacts. We believe that a strong and enduring commitment to the health and safety of our workforce best reflects our values and underpins and sustains optimal business performance. -

Codrus Minerals Limited (ASX:CDR, “Codrus”, Or the “Company”) Is Pleased to Report on Activities at Its Exploration Projects During the June 2021 Quarter

ASX ANNOUNCEMENT 22 July 2021 JUNE 2021 QUARTERLY REPORT Codrus lists on ASX after completing $8m IPO, commences maiden drilling program at Silver Swan South Highlights • Heavily oversubscribed $8m IPO at $0.20 completed on the 23rd June 2021. • 75m shares with $15m market cap and $7m enterprise value at listing. • Leveraged to exploration success with a high-quality project portfolio in Tier-1 locations. • Blackstone Minerals (ASX: BSX) remains cornerstone shareholder with 35m shares (46%). • Exploration programs planned to target projects in Australia and the USA. Codrus Minerals Limited (ASX:CDR, “Codrus”, or the “Company”) is pleased to report on activities at its exploration projects during the June 2021 Quarter. Corporate The official ASX listing of Codrus Minerals Limited occurred as planned on the 23rd of June 2021. A very well-supported Initial Public Offering was completed raising $8 million (before costs). The Company is now in a strong financial position to evaluate and explore its range of exciting projects in Tier-1 jurisdictions. Work Completed Since listing, the Company has focused its efforts on preparing for its maiden drilling program at the Silver Swan South Project (see below) and progressing planning for upcoming exploration across its high-quality project portfolio in the coming Quarter. Forward Plan During the September Quarter, exploration is planned to commence at all of the Company’s projects. WESTERN AUSTRALIAN PROJECTS The Company has three (3) projects in Western Australia. The Silver Swan South and Red Gate projects are located in the Kalgoorlie region and the Middle Creek Project is located near Nullagine in the Pilbara (Figure 1). -

Financial Report 30 June 2019

Codrus Minerals Limited (formerly known as Black Eagle (WA) Pty Ltd) ABN 17 600 818 157 Annual Report - 30 June 2019 Contents Corporate Directory 2 Directors’ Report 3 Auditor’s Independence Declaration 10 Financial Report 12 Directors’ Declaration 28 Independent Auditor’s Review Opinion 29 1 Corporate Directory Directors Auditors Andrew Radonjic Stantons International Shannan Bamforth Level 2 Jamie Byrde 1 Walker Avenue Stuart Owen WEST PERTH WA 6005 Company Secretary Jamie Byrde Bankers National Australia Bank Principal & Registered Office 50 St Georges Terrace Level 3, 24 Outram Street PERTH WA 6000 West Perth WA 6005 Telephone: (08) 9425 5217 Website Address Facsimile: (08) 6500 9982 www.codrusminerals.com.au Lawyers Steinepreis Paganin Lawyers & Consultants Level 4, 16 Milligan Street Perth WA 6000 Australia 2 Codrus Minerals Limited Directors' report 30 June 2019 The Directors present their report, together with the financial statements, on the consolidated entity (referred to hereafter as the 'Group') consisting of Codrus Minerals Limited (formerly known as Black Eagle (WA) Pty Ltd) (referred to hereafter as the 'Company' or 'Parent Entity') and the entities it controlled at the end of, or during, the year ended 30 June 2019. Directors The following persons were directors of Codrus Minerals Limited during the whole of the financial year and up to the date of this report, unless otherwise stated: Andrew Radonjic (Appointed on 1 August 2017) Shannan Bamforth (Appointed on 29 March 2021) Jamie Byrde (Appointed on 1 January 2021) Stuart Owen (Appointed on 1 January 2021; Resigned on 29 March 2021) Principal activities The principal activity of the Group during the year was mineral exploration. -

St Ives Gold Mine Technical Short Form Report 31 December 2012 1

St Ives Gold Mine Technical Short Form Report 31 December 2012 1. Overview The St Ives Gold Mining Company (Proprietary) Limited (St Ives) Salient featuru ess is wholly owned by Gold Fields Limited and is situated some 80 kilometres south of Kalgoorlie. The St Ives operations are X Mineral Resources at 4.7 Moz. conducted within mining tenements comprising 277 mining X Mineral Reserves at 2.2 Moz. titles (54,749 hectares), three mineral titles (364 hectares), 13 exploration licences (27,192 hectares), 22 prospecting X High-cost heap leach operation closed. licences (2,700 hectares) and 19 miscellaneous licences X Highly prospective tenement delivered new (14,500 hectares) for a total area of approximately exploration camp and Mineral Resources at 99,594 hectares. St Ives has security of tenure for all current Invincible. mining titles and exploration licences that contribute to the X Mineral Reserves. Neptune Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves continue to grow; detailed technical St Ives represents a solid base for growth in Australia and is an planning initiated. important contributor to the Gold Fields’ vision of being “the X Hamlet well on track to achieve full production global leader in sustainable gold mining” with a target contribution in 2013. from the Australasia Region of approximately 0.7 Moz per annum X Life of Mine extends to 2018 (6 years). by 2015. St Ives currently operates four underground mines accessed via declines and several open pits, a centralised administrative office, an engineering workshop and CIP processing plant. Declared Mineral Resources at St Ives decreased by 490 koz primarily due to depletion and closure of the Leviathan, Formidable, Dianna, Minotaur and Britannia Footwall pits during 2012. -

708 KB 18Th Apr 2019 Bridge St Capital

Dr Chris Baker April 2019 LEFROY EXPLORATION LTD LEX:AU, $0.20. Market cap A$16.2 m Air core results confirm two gold trends under Lake Lefroy Recent site visit confirms prospectivity of other LEX targets - Gold Fields has released its first tranche of drill results from air core drilling on the LEX-JV, east of the world class St Ives gold project. - Results confirm the existence of two gold-anomalous trends beneath Lake Lefroy. - The immediate target is a 3km zone along the inferred Woolibar Fault centred on the Zanex prospect. - The Eastern Shoreline Trend has identified a +3km zone of gold anomalism. - Both trends are worthy of follow-up with RC or diamond drilling, likely to happen in 2H19 - LEX will continue to focus on Lucky Strike and other 100%-owned projects to the east of Lake Lefroy. A 2000m RC/diamond programme is currently underway. - LEX is a very inexpensive WA exploration play strongly leveraged to GFI’s aggressive exploration programme on Lake Lefroy, and to exploration within its 100%-owned tenements in the Mt Monger area. Expect plenty of exploration news over the rest of the year. Warm colours (red/purple) signify higher gold grades. Source: From ASX release 15 April 2019 LEFROY EXPLORATION (ASX: LEX) | Research report FIRST EXPLORATION RESULTS FROM THE GOLD FIELDS JOINT VENTURE LEX holds tenements covering nearly 600km2 to the east of and adjoining Gold Fields’s 100%-owned St Ives gold mine and were recently joint ventured with Gold Fields (GFI). As discussed in more detail below, GFI can earn up to 70% of LEX’s western Lake Lefroy tenements with the expenditure of A$25m.