Download Studio Research Issue #4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a Close Reading of Contemporary Graphic Novels

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a close reading of contemporary graphic novels Abstract: The study offers an alternative analytical framework for thinking about the contemporary graphic novel as a dynamic area of visual art practice. Graphic narratives are placed within the broad, open-ended territory of investigative drawing, rather than restricted to a special category of literature, as is more usually the case. The analysis considers how narrative ideas and energies are carried across specific examples of work graphically. Using analogies taken from recent academic debate around translation, aspects of Performance Studies, and, finally, common categories borrowed from linguistic grammar, the discussion identifies subtle varieties of creative processing within a range of drawn stories. The study is practice-based in that the questions that it investigates were first provoked by the activity of drawing. It sustains a dominant interest in practice throughout, pursuing aspects of graphic processing as its primary focus. Chapter 1 applies recent ideas from Translation Studies to graphic narrative, arguing for a more expansive understanding of how process brings about creative evolutions and refines directing ideas. Chapter 2 considers the body as an area of core content for narrative drawing. A consideration of elements of Performance Studies stimulates a reconfiguration of the role of the figure in graphic stories, and selected artists are revisited for the physical qualities of their narrative strategies. Chapter 3 develops the grammatical concept of tense to provide a central analogy for analysing graphic language. The chapter adapts the idea of the graphic „confection‟ to the territory of drawing to offer a fresh system of analysis and a potential new tool for teaching. -

Anne-Marie Creamer

Anne-Marie Creamer Education 1988-90 Royal College of Art. M.A, Fine Art, painting 1985-8 Middlesex University. B.A. Fine Art Awards and Residencies 2014 MOVING LANDSCAPE #2, Puglia, Italy, public art project on Rete dei Caselli Sud Est trainwork, curated by Francesca Marconi, with Francesco Buonerba & Elisabetta Patera, including workshop on the dramaturgy of territory, commission & publication, supported by PepeNero, Projetto GAP, Fondazione con il Sud, & European Commission. 2013 EMERGENCY6 “People’s Choice” award, Aspex Gallery 2013 Sogn og Fjordane Fylkeskommune, Norway, for post-production & exhibition costs of ‘The Life and Times of the Oldest Man in Sogn og Fjordane’. 2013 European Regional Development Fund Award - New Creative Markets Programme with Space Studios 2012 British School at Rome, Derek Hill Scholarship, Rome. 2011 CCW Graduate School Staff Fund, awarded by Chelsea, Camberwell and Wimbledon Colleges of Art, University of the Arts London 2003-4 Evelyn Williams Drawing Fellowship, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK 2003 Arts & Humanities Research Council, Small Grants in the Creative & Performing Arts 2003 Grants for Individuals, Arts Council of England, London 2003 International-artist-in-residence-award, Center for Contemporary Art, Prague, Czech Republic 2001 London Arts Development Fund: London Visual Arts Artists Fund, London Arts Board 2001 Go! International Award’, London Arts Board 1997 Award to Individual Artists, London Arts Board 1993 Artists Bursary, Arts Council of Great Britain. 1992 European Travel Award, Berlin, The Princes Trust 1991 The Union of Soviet Art Critics Residency, U.S.S.R- Russia, Latvia, Uzbekistan & the Crimea 1991 Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool 1990-2 The Delfina Studios Trust Award, London 1990 Basil H. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETII-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND THEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTIIORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISII ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME III Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA eT...........................•.•........•........................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................... xi CHAPTER l:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION J THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

ASSOCIATION of ART HISTORIANS Registered Charity No

February 1994 BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS Registered Charity No. 282579 Editor: Jannet King, 48 Stafford Road, Brighton BNI 5PF For information on advertising & membership: Kate Woodhead, Dog and Partridge House, Bxley, Cheshire CWW 9NJ Tel: 0606 835517 Fax: 0606 834799 CHAIR'S REPORT During the autumn the Officers and the put more pressure on Vice-Chancellors for potential sponsors to the Director of Executive Committee of the Association and on the Funding Council itself to have Publicity and Administration. have taken up a number of issues of interest the system amended. Benefactors - Change your terms of to the membership. membership to become a Benefactor. Art History Departments' E-Mail We have also received the excellent Art History Teaching in Scottish Network news that the Association will no longer be Universities The Association wishes to establish an E- charged VAT on subscriptions and other The Scottish Higher Education Funding Mail network to keep colleagues working business. This will save us substantial Council is about to embark upon a Quality in Art History departments across the amounts every year. Many congratulations Assessment Programme for Humanities country more closely in touch with one and thanks to Peter Crocker for his patient subjects in the academic year 1995-96. another. E-mail addresses to the Chair negotiations with HM Customs & Excise. The Association has written to the Director please. 1994 Bookfair: It is vital to the of Teaching and Learning making a case Association's finances that this event is a for Art History to be assessed separately Review of the Academic Year success. -

2020 Celebrating 800 Years of Spirit and Endeavour

2020 CELEBRATING 800 YEARS OF SPIRIT AND ENDEAVOUR, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury. Texts by Sandy Nairne and Jacquiline Cresswell. 2019 OBJECTS OF WONDER: BRITISH SCULPTURE FROM THE TATE COLLECTION 1950S -PRESENT. Deutsche Bank AG, Frankfurt, Germany A COOL BREEZE. Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague, Czech Republic. Text by Petr Nedoma. LESS IS MORE. Museum Voorlinden, Wassenar. Texts by Suzanne Swarts, Aaf Brandt Corstius, Rafael Rozendaal and Witeke van Zeil. 2018 WOHIN DAS AUGE REICHT: NEUE EINBLICKE IN DIE SAMMLUNG WÜRTH. Swiridoff, Künzelsau, Germany. Sean Rainbird et al. BIENALLE INTERNATIONALE SAINT-PAUL DE VENCE. Editions DEL'ART, Saint-Paul de Vence, France. Text by Loic Deltour. SUTRA. Sadler's Wells, London. Author unknown. 2017 RODIN, LE LIVRE DU CENTENAIRE, Les éditions Rmn-Grand Palais, Paris, France. VERSUS RODIN, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Australia. Texts by Tony Magnusson, Lisa Slade, Leigh Robb et al BLICKACHSEN 9, Wienand Verlag, Cologne, Germany. Oliver Kaeppelin et al. EUROVISIONS: CONTEMPORARY ART FROM THE GOLDBERG COLLECTION, National Art School, Sydney, Australia. Texts by Judith Blackhall (ed.) et al. GOLEM: AVATAR D'UNE LEGENDE D'ARGILE, Éditions Hazan / Musée d'art et d'histoire du Judaïsme, Paris. Texts by Ada Ackerman et al. INTUITION, AsaMer, Gent, Belgium. Text by Margaret Iverson et al. FOLKESTONE TRIENNIAL 2017. Creative Foundation, Folkestone, England. Text by Lewis Biggs ARTISTS WORKING FROM LIFE. Royal Academy of Arts, London. Texts by Martin Gayford et al. WOW! THE HEIDI HORTEN COLLECTION, WOW! The Heidi Horten Collection, Vienna, Austria. Husslein-Arco et al. GOLEM: AVATAR D'UNE LEGENDE D'ARGILE, Éditions Hazan / Musée d'art et d'histoire du Judaïsme, Paris. -

Jerwood Drawing Prize 2015 Catalogue

JERWOOD DRAWING PRIZE 2015 Published to accompany Jerwood Drawing Prize Jerwood Visual Arts 2015 exhibition 171 Union Street London SE1 0LN Copyright © Jerwood Drawing Prize & United Kingdom Jerwood Charitable Foundation. Published to accompany the All or part of this publication may not be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems or Jerwood Drawing Prize 2014 transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, & touring exhibition. including photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. Copyright © Jerwood Drawing Prize & Jerwood Charitable Foundation. Catalogue Editors: Anita Taylor and Parker Harris All or part of this publication may not be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems Photography: Benjamin Cosmo Westoby; photograph p34, Peter Stone or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, Designed by: Matthew Stroud including photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in Printed by: Jigsaw writing of the publisher. ISBN 978-1-908331-17-5 Catalogue Publication Editors: Anita Taylor and Parker Harris Photography: Benjamin Cosmo Westoby Designed by: Matthew Stroud and Parker Harris Printed by: Swallowtail ISBN 978-1-908331-17-5 CONTENTS 4 Jerwood Drawing Prize 2015 exhibition & tour 5 Foreword, Shonagh Manson 6 Introduction, Professor Anita Taylor 8 The Selection Panel 9 Selection Panel Perspectives: Dexter Dalwood Salima Hashmi John-Paul Stonard 12 Catalogue of Works 70 Artists’ Biographies 80 About Jerwood -

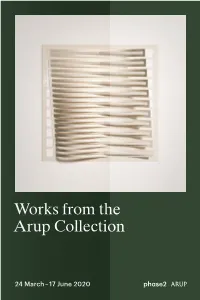

Works from the Arup Collection Works from the Arup Collection

Works from the Arup Collection Works from the Arup Collection Cover Kisa Kawakami, Arc IV, 1986 Introduction The Arup Collection has its origins in the earliest years of the firm. This exhibition shows a selection of works from the Collection in different media as well as furniture from the first offices. Ove Arup had a keen interest in the arts. In 1948, two years after the firm was registered, he became a member of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London and retained an enthusiasm for collecting throughout his life which was shared by the founding partners. There was no obvious strategy when building the Arup Collection, although nearly all the artists of different nationalities were UK-based and prints and drawings were favoured – perhaps not surprising given that good draughtsmanship was integral to the world of the engineer at that time. Many of the works are by artists who pushed the boundaries of their medium in the post-war period like R B Kitaj, who sought Arup’s assistance with the construction of his home and studio, and John Piper whom Arup worked with on Coventry Cathedral. Just as Ove Arup supported Fig 1 Ronald Jenkins’ office, 8 Fitzroy Street, London, 1952 (table designed by Alison and Peter Smithson, wall cabinet ‘rebel architects’ of the modernist movement (he was a member of the by Victor Pasmore and ceiling by Eduardo Paolozzi) MARS Group), this interest was also evident in the art that was collected. Photographer John R Pantlin The Collection was largely based on the relationships the partners developed with artists and architects. -

Kelly Long Bio2008

MARY KELLY Mary Kelly is known for her project-based work, addressing questions of sexuality, identity and historical memory in the form of large-scale narrative installations. She studied painting in Florence, Italy, in the sixties, and then taught art in Beirut, Lebanon during a time of intense cultural activity known as the “golden age”. In 1968, at the peak of the student movements in Europe, she moved to London, England to continue postgraduate study at St. Martin's School of Art. There, she began her long-term critique of conceptualism, informed by the feminist theory of the early women's movement in which she was actively involved throughout the 1970s. She was also a member of the Berwick Street Film Collective and a founder of the Artists' Union. During this time, she collaborated on the film, Nightcleaners, 1970-75, and the installation, Women & Work: a document on the division of labor in industry, 1975, as well as producing her iconic work on the mother/child relationship, Post-Partum Document, 1973-79. Documentation I, the infamous “nappies”, caused a scandal in the media when it was first exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in 1976. In 1989 she joined the faculty of the Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Her four part work interrogating women's relation to the body, money, history and power, Interim, 1984-89, was shown in its entirety at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in 1990 and the symposium that was organized in conjunction with it, On the Subject of History, marked a highpoint in the feminism and postmodernism debate instigated by the critic, and early supporter of Kelly's work, Craig Owens. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Liliane Lijn 93 Vale Road London N4 1TG Telephone and Fax: 0208 809 5636 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.lilianelijn.com http://www.lilianelijn.com 1939 Born in New York City 1958 Studied Archaeology at the Sorbonne and Art History at the École du Louvre in Paris Interrupted these studies to concentrate on painting Took part in meetings of the Surrealist group 1961-62 Lived in New York; worked with plastics, using fire and acids First work with reflection, motion and light, research into invisibility at MIT Married the artist Takis. With whom she had a son, Thanos (b.1962) 1963-64 Worked in Paris; exhibited first kinetic light works and Poem Machines 1964-66 Lived in Athens, making use of natural forces in her sculpture 1966 Moved to London. Divorced Takis in 1970 Invented kinetic clothing Worked with poetry, light, movement and liquids 1967-74 Lijn’s interest in Buddhism and in quantum and solid state physics inspired her to write Crossing Map, an autobiographical prose poem In 1969, Lijn decided to make London her base, with photographer and industrialist Stephen Weiss with whom she had two children, Mischa (b.1975) and Sheba (b.1977) 1971 Began receiving commissions to design and make large public sculptures 1974 Lijn staged the performance The Power Game, a text-based gambling game and socio-political farce for the Festival for Chilean Liberation at the RCA 1975 Completed her first 16mm film What Is the Sound of One Hand Clapping? 1983 Publication of Crossing Map (London and New York: Thames & Hudson) 1983-90 Member of the Council of Management of the Byam Shaw Art School 1986 Exhibited Conjunction of Opposites, a computer controlled sculpture drama, at Arte e Scienza, Venice Biennale XLII 1996-98 Completed the artist’s book, Her Mother’s Voice. -

Matt Lodder As Our Acting Co-Ordinator While Claire Davies Is on Maternity Leave

AAH ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS BULLETIN www.aah.org.uk For information on advertising, membership and distribution contact: AAH Administrator, 70 Cowcross Street, London EC1M 6EJ 100 Tel: 020 7490 3211; Fax: 020 7490 3277; <[email protected]> Editor: Jannet King, 48 Stafford Road, Brighton BN1 5PF <[email protected]> FEB 2009 ART HISTORY SCORES WELL IN RAE Report from the AAH Chair and the Teaching, Learning and Research Committee here have been a number of changes which you may just be noticing as Tyou get ready to renew your annual subscription for 2009. The first is the Greetings from change in membership subscription, which has significantly reduced the cost of joining the AAH while still allowing those who wish to subscribe to our publications to benefit from heavily discounted rates. The second is the arrival of Matt Lodder as our acting co-ordinator while Claire Davies is on maternity leave. We are delighted to have him as part of our team and wish Claire all the best. The Executive spent much of the Autumn reviewing our activities and setting goals. For example, we want the Annual Conference to act as a showcase for the best Art History in Britain, and our student activities to ensure that there is a strong investment in the next generation of Art Historians. We will look forward to seeing many of you in Manchester in April for the AAH annual conference, which promises to help us achieve both ambitions. There will be much to discuss and to celebrate. We will be joined at our Annual General Meeting by Sandy Heslop, the Chair of the I have recently been appointed 2008 Research Assessment Exercise panel for the History of Art, Senior Administrator, to run the Architecture and Design, who will provide an overview of our field and of day-to-day business of the the decision-making process. -

Notes on the Artist Adrian Berg Wa

FRESTONIAN GALLERY APPLICATION FOR FRIEZE MASTERS SPOTLIGHT SECTION ADRIAN BERG (1929-2011) Notes on the artist Adrian Berg was born in London in 1929. He was educated at Charterhouse and Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge. He studied art in London, first at Central St Martin's, then Chelsea College of Arts and finally at the Royal College of Art, later he would go on to teach at the Royal College, becoming senior tutor in 1987. Berg’s paintings have been exhibited in all major UK institutions including, amongst many others the Tate, Hayward Gallery, Royal Academy, Victoria & Albert Museum, Fitzwilliam and Pallant House Gallery. In 1986, The Serpentine Gallery and the Arts Council held a major retrospective of Berg’s work which subsequently toured the country. He has also exhibited extensively internationally. In 1992, he was elected as a Royal Academician, and in 1994 he became an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Art. His work is held in many private and public collections, including the Arts Council Collection, the Tate, the Government Art Collection, the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum. Berg died in 2011. Selected Solo Exhibitions 1964, ‘67, ‘69, ‘72 & ‘75 Arthur Tooth & Sons, London 1973 Galleria Vaccarino, Florence 1976 Galerie Burg Diesdonk, Düsseldorf 1978 Waddington & Tooth Galleries, London Yehudi Menuhin School, Surrey 1979 Waddington Galleries, Montreal and Toronto Hokin Gallery Inc., Chicago 1980 Rochdale Art Gallery 1981 & ‘83 Waddington Galleries, London 1984 Serpentine Gallery (South Gallery), London -

What I Have Done

What I have done ANDREW BRACEY AUG 01, 2018 07:31PM ANDREW BRACEY JUL 07, 2018 07:35AM What I have done in July 2018Andrew Activities Bracey 1 June – Hosted and spoke at CVAN EM Document event at University of Lincoln Activities 1, 21 June – Dyslexia software training 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 1 June – Opening of Project Space at General Practice 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 July – reading and note taking for PhD 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 17, 18,19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 2, 3, 9, 16, 17, 23, 24, 25, 30, 31 July – Worked at University of 27, 28, 29, 30 June – reading and note taking for PhD Lincoln doing research, admin, meetings and teaching and 3 June – Looked through rst draft of Bummock: The Lace running MA Fine Art Archive catalogue with Danica Maier 4 July – PhD Supervisory meeting with Catherine George 4 June – External examining at Anglia Ruskin University and Steve Klee 5, 6, 11, 14, 15, 18, 20, 21 June – Worked at University of 5 July – Dyslexia software training Lincoln doing research, admin, meetings and teaching and 5, 18, 30 July – meeting with Stewart Collinson about running MA Fine Art collaborative working together 4 June – meeting with Mansions of the Future for future 5 July – First Approaching Affective Zero meeting at planning Mansions of the Future 5 June – Met with John Cairns form ACE about link ups to 6 July – Met with other artists and spoke at CVAN EM students Document event at Phoenix, 7 June – Interviewed by Paula Serani from CAMEO as part 9-13 July –