Counter-Forensics and Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Teresa Hubbard 1St Contact Address

CURRICULUM VITAE Teresa Hubbard 1st Contact address William and Bettye Nowlin Endowed Professor Assistant Chair Studio Division University of Texas at Austin College of Fine Arts, Department of Art and Art History 2301 San Jacinto Blvd. Station D1300 Austin, TX 78712-1421 USA [email protected] 2nd Contact address 4707 Shoalwood Ave Austin, TX 78756 USA [email protected] www.hubbardbirchler.net mobile +512 925 2308 Contents 2 Education and Teaching 3–5 Selected Public Lectures and Visiting Artist Appointments 5–6 Selected Academic and Public Service 6–8 Selected Solo Exhibitions 8–14 Selected Group Exhibitions 14–20 Bibliography - Selected Exhibition Catalogues and Books 20–24 Bibliography - Selected Articles 24–28 Selected Awards, Commissions and Fellowships 28 Gallery Representation 28–29 Selected Public Collections Teresa Hubbard, Curriculum Vitae - 1 / 29 Teresa Hubbard American, Irish and Swiss Citizen, born 1965 in Dublin, Ireland Education 1990–1992 M.F.A., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Canada 1988 Yale University School of Art, MFA Program, New Haven, Connecticut, USA 1987 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine, USA 1985–1988 University of Texas at Austin, BFA Degree, Austin, Texas, USA 1983–1985 Louisiana State University, Liberal Arts, Baton Rouge, USA Teaching 2015–present Faculty Member, European Graduate School, (EGS), Saas-Fee, Switzerland 2014–present William and Bettye Nowlin Endowed Professor, Department of Art and Art History, College of Fine Arts, University of Texas -

Allan Sekula from June 14 to September 25, 2017

www.fundaciotapies.org no.5 Allan Sekula from june 14 to september 25, 2017 Allan Sekula. Collective Sisyphus draws a straight line between Fish Story (1989–95), one of his better-known photographic essays, and his last work project Ship of Fools / The Dockers’ Museum (2010–13). Along this trajectory, we findDeep Six / Passer au bleu (1996/98) and the film Lottery of the Sea (2006). In all of them Sekula laments the loss of the sea due to a global economy that favors a connected world. Sekula’s work will be remembered as one of modern photography’s biggest efforts to erect a monument – a far from grandiloquent one – to the cosmopolitan proletariat. LeveL 1 p.2 LeveL 1 p. 3 l components, the worldly belongings of military de- Fish Story, 1989–95 Growing up in a harbor predisposes one to retain pendents, cocaine, scrap paper (who could know?) quaint ideas about matter and thought. I’m speak- hidden behind the corrugated sheet steel walls em- ing only for myself here, although I suspect that a blazoned with the logos of the global shipping cor- Chapter 1 certain stubborn and pessimistic insistence on the porations: Evergreen, Matson, American President, primacy of material forces is part of a common cul- Mitsui, Hanjin, Hyundai. ture of harbor residents. This crude materialism is underwritten by disaster. Ships explode, leak, sink, 4 collide. Accidents happen every day. Gravity is Space is transformed. The ocean floor is wired for recognized as a force. By contrast, airline compa- sound. Fishing boats disappear in the Irish Sea, nies encourage the omnipotence of thought. -

Allan Sekula En Galicia: Dos Series Fotográficas Sobre Trabajo, Capitalismo Y Crisis

Allan Sekula en Galicia: dos series fotográficas sobre trabajo, capitalismo y crisis Allan Sekula in Galicia: two photograpy series on work, capitalism and crisis Miguel Anxo Rodríguez González Universidad de Santiago de Compostela Fecha de recepción: 2 de enero de 2020 Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte Fecha de aceptación: 10 de julio de 2020 vol. 32, 2020, pp. 137-159 ISSN: 1130-5517, eISSN: 2530-3562 https://doi.org/10.15366/anuario2020.32.007 RESUMEN ABSTRACT Allan Sekula, uno de los principales referentes de la Allan Sekula, one of the main referents in documentary fotografía documental, realizó dos series en Galicia: photography, carried out two series in Galicia: Mensa- Mensaxe nunha botella (1992) y Black Tide/Marea xe nunha botella (1992) and Black Tide/Marea negra negra (2002-2003), resultado de dos encargos, el pri- (2002-2003), as a result of commissions from the mero de la Fotobienal de Vigo y el segundo del periódi- Fotobienal de Vigo and from a newspaper, La Van- co La Vanguardia. El fotógrafo centró su atención en guardia. He focused on works and people related to trabajos y personas relacionados con el mar, desde esti- the sea, from dock workers to volunteers and sailors badores hasta voluntarios y marineros involucrados en involved in the cleaning of the coast after the accident la limpieza de la costa tras el accidente del petrolero of the oil tanker Prestige. This investigation aims at Prestige. Esta investigación se propone analizar las analysing the photoworks, explaining the circumstan- series, explicar las circunstancias de su realización y ces of their production and answering the question of responder a la pregunta de hasta qué punto, tratándose how far, in the case of commissions, the photographer de encargos, el fotógrafo se mantuvo fiel a su programa remained faithful to his programme for a “new docu- para la “nueva fotografía documental”, establecido en mentary photography”, established in the early years los primeros años de su trayectoria. -

ALLAN SEKULA: OKEANOS Art Contemporary 21 February – 14 May 2017 Köstlergasse 1, 1060 Wien +43 1 513 98 56 48 [email protected]

PRESS INFORMATION Thyssen-Bornemisza ALLAN SEKULA: OKEANOS Art Contemporary 21 February – 14 May 2017 Köstlergasse 1, 1060 Wien +43 1 513 98 56 48 [email protected] Ausstellungen / Exhibitions “Most sea stories are allegories of authority. In this sense alone politics is Scherzergasse 1A, 1020 Wien +43 1 513 98 56 24 never far away." — Allan Sekula [email protected] tba21.org facebook.com/tba21 twitter.com/tba21 instagram.com/tba_21 Allan Sekula, Middle Passage, chapter 3, Fish Story, 1994 Photo: The Estate of Allan Sekula, 1994 Allan Sekula: OKEANOS is a monographic exhibition that explores the legacy of Allan Sekula (American, 1951–2013) by charting the artist’s research into the world’s largest and increasingly fragile hydrosphere: our oceans. The exhibition title is a reference to the figure of Okeanos – the son of Gaia, the mythical goddess of the earth – who ruled over the oceans and water. His aquatic perspective – from and of the oceans – represents a shift of focus that counters the terrestrial narratives of even the most advanced contemporary discourses on the environment. Drawing from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) collection, the exhibition features a selection of seminal works from Sekula’s multi-faceted oeuvre. Three chapters from Sekula’s magnum opus “Fish Story” evocatively document maritime spaces and the effects of globalization. By describing shifting labor locations and relations, complexities of containerization, shipping logistics and economic pressures, “Fish Story” weaves observations of global socio-political and economic configurations and explores histories of the seas. Other important works featured in the exhibition include two films: “Tsukiji” 2001, and “Lottery of the Sea” 2006, as well as photographic works from Sekula’s series “Black Tide / Marea negra” 2002–03: “Large and small disasters” (Islas Cíes and Bueu, 12-20-02), 2002–2003 and “Self-portrait” (Lendo, 12-22-02), 2002–03. -

A Film About the Sea Notes on Allan Sekula and Noël Burch's The

A Film About the Sea Notes on Allan Sekula and Noël Burch’s The Forgotten Space Published in 2012 by Centre for European Studies Halifax Independent Filmmakers Festival 1376 LeMarchant Street c/o Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative Dalhousie University 5663 Cornwallis Street, Suite 101 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 4P9, Canada Halifax, Nova Scotia B3K 1B6, Canada Copyright © Individual Contributors ISBN 978-0-7703-0031-9 Images (and exhibition copy of The Forgotten Space) supplied by Doc.EyeFilm Van Hallstraat 52 1051 HH Amsterdam, Holland Ph: 31.20.686.5687 Email: [email protected] www.doceyefilm.nl www.theforgottenspace.net Printed in Canada Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................7 Dismal Science: Part 1 (Excerpt) ...............................11 The Forgotten Space: Notes for a Film .......................17 Sea Change: The Displacements of The Forgotten Space ..............................................21 Explaining the Notion of the “Essay Film” ................31 Making Political Cinema - The Forgotten Space ..........37 Noël Burch, Theory of Film Practice, and The Forgotten Space ..............................................43 Contributors’ Notes ..................................................47 Jose Ramón Velazquez truckdrivers Los Angeles 7 Introduction The Forgotten Space is a film that seems to be made for the Halifax Independent Filmmakers Festival. It takes as its subject the life of the port, and tries to show us what kind of global systems the port city enables and unwittingly participates in. One of its co-directors is Allan Sekula, one of the great American photographers who taught, for a period in the 1980s, at NSCAD. Its other director is Noël Burch, an expatriate living in France whose book Praxis du cinéma, also published as Theory of Film Practice, helped form the first generation of film studies and is still an indispensible work of film theory. -

PHOTOGRAPHY BETWEEN LABOUR and CAPITAL by Allan Sekula 193

MINING PHOTOGRAPHS AND OTHER PICTURES 1948-1968 A Selection from the Negative Archives of Shedden Studio, Glace Bay, Cape Breton PHOTOGRAPHS BY LESLIE SHEDDEN Essays by Don Macgillivray and Allan Sekula Introduction by Robert Wilkie fHOTOG . Edited by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh and Robert Wilkie 1)-< .:.. 2.., SSL!\ 1 I I ~ The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design . l~3 and The University College of Cape Breton Press Published by The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design 5163 Duke Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3J 3J6 Tel. (902) 422-7381 Co-published by The University College of Cape Breton Press P.O . Box 5300, Sydney, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Canada B1 P 6L2 Tel. (902) 539-5300 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Shedden, Leslie Mining Photographs and Other Pictures, 1948-1968 (The Nova Scotia series; v. 13) ISBN 0-919616-25-9 1. Coal mines and mining - Nova Scotia - Glace Bay - History - 20th century. 2. Miners - Nova Scotia - Glace Bay. 3. Photography of coal mines. 4 . Shedden, Leslie . I. Buchloh, Benjamin H. D. II. Wilkie, Robert. Ill. Title. IV. Series: The Nova Scotia series: source materials of the contemporary arts; V. 13. HD9554.C23G55 338.2'724'0971695C83-094174-6 Copyright 1983 Shedden Studio, Glace Bay, The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax All rights reserved Design and production by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Allan Scarth Published 1983 and Bob Wilkie Printed and bound in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Pressman : Guy Harrison M J. PAUL GETTY CENTER LIBRARY CONTENTS -

A Hard, Merciless Light the Worker Photography Movement, 1926-1939 the Worker Photography Movement, 1926-1939

Fotografía obrera inglés:Maquetación 1 30/03/11 12:27 Página 1 April 6 – August 22, 2011 Museo Nacional ACTIVITIES Centro de Arte Reina Sofía A Hard, Merciless Light Jorge Ribalta. Sabatini Building Capa, Kertész and Brassaï from Hungary, David Seymour A Guided Visit to the Exhibition Santa Isabel, 52 (Chim) from Poland, the Germans Gerda Taro and The Worker Photography Curator’s talk Nouvel Building Germaine Krull, and the Romanian Eli Lotar. April 6, 2011. 7:00 p.m. Ronda de Atocha (corner plaza Emperador Carlos V) Movement, 1926-1939 Although Münzenberg was also in Paris, his role in the A Hard, Merciless Light. 28012 Madrid Comintern declined. Nonetheless, his model of public The Worker Photography Movement, 1926–1939 participation through the figures of prestigious Guided Tours Tel: 91 774 10 00 intellectuals inspired the First Conference of Writers in This exhibition is devoted to the history of amateur, proletarian documentary Thursdays at 7:15 p.m. at the Meeting Point Fax: 91 774 10 56 Defense of Culture in 1935, which marked a high point in photography, a movement that dates back to March 1926 when the German Free activity, prior enrolment not required the activities of the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Museum hours communist magazine AIZ (Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung) called on amateur Révolutionnaires (AEAR) founded two years before and The Forgotten Space. Monday to Saturday photographers to send in their contributions. It was structurally linked to the connected with the French Communist Party (PCF). A Film Essay by Allan Sekula and Noel Bürch from 10.00 a.m. -

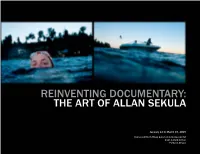

The Art of Allan Sekula

REINVENTING DOCUMENTARY: THE ART OF ALLAN SEKULA January 22 to March 15, 2015 Ronna and Eric Hoffman Gallery of Contemporary Art Lewis & Clark College Portland, Oregon FROM THE DIRECTOR I had the great good fortune to know Allan Sekula (1951–2013) in the early 1980s, when we were both at The Ohio State University. Allan was a young and brash new faculty member in The Film Studies Program; I was completing my MA in the history of art. He gained a certain noto- riety and maybe even a bit of academic celeb status for taking part in a protest with his friend and eventual collaborator, Noël Burch, a film critic and fellow faculty member. The demonstration was against US involve- ment in Central America; both men wore Ronald Reagan masks. When a student reporter asked the masked Sekula to identify himself, he tore off his mask; the resulting pic landed in the OSU student newspaper. It was pretty funny, except not so much to the OSU administration. There War Without Bodies Military air show and Gulf War victory celebration, were some real and unpleasant consequences. For all that Sekula’s El Toro Marine Corps Air Station, Santa Ana, work comprises—compelling imagery, penetrating criticism, biting polit- California, 28 April 1991 PHOTOGRAPH BY WERNER KALIGOFSKY, GENERALI FOUNDATION, VIENNA GENERALI FOUNDATION, PHOTOGRAPH BY WERNER KALIGOFSKY, 1991/1996 ical and social commentary, fearless polemics, daring performance, and rapier wit—perhaps he hoped most that his work would engender real his thinking process and further evidence of his extraordinarily broad Fisher, assistant professor of art and studio head of photography at consequences that would positively affect the world. -

Allan Sekula Polónia És Más Mesék Polonia and Other Fables 1

1 ALLAN SEKULA Polónia és más mesék Polonia and Other Fables 1 ALLAN SEKULA Polónia és más mesék | Polonia and other Fables „…nagyrészt inkább írok mert a kamera korlátozott ábrázolóké- “…to a larger extent i am writing because of the limited representa- 2010. július 9 – szeptember 19. | July 9—September 19, 2010 pessége miatt nem fényképezhet az ember ideológiákat viszont az tional range of the camera one cannot photograph ideol ogy but one ember miután elkészített egy fényképet és egy lépést hátralépve can make a photograph step back and say look in that photograph kurátor | curated by fordító | translated by megnézi azt mondja no lám ezen a fotón ott van az ideológia ott van there is ideology between those two photographs there is ideology Karolina LEWANDOWSKA, SZÉKELY Katalin Iain COULTHARD az ideológia a között a két fotó között ott van ez meg az és ez meg there is such and such and such relates to such…”1 az összefügg ezzel meg azzal…”1 Allan Sekula (Erie, Pennsylvania, 1951) is one of the most outstand- együttmûködô partner | in collaboration with korrektúra | proofreading Allan Sekula (Erie, Pennsylvania, 1951) a kortárs dokumenta- ing contemporary documentarians. His series of photographs, films ZACHĘTA National Gallery of Art, Warsaw KÜRTI Emese, Adèle EISENSTEIN rizmus egyik legmeghatározóbb alakja. Fotósorozatai, filmjei és and – last, but not least – photo-historical and theoretical studies2 – nem utolsósorban – fotótörténeti és elméleti tanulmányai2 a do- are directed toward the continuous, critical renewal and reinter- külön köszönet | special thanks grafikai terv |graphic design kumentarista mûfaj és gondolkodás állandó, kritikai megújítását és pretation of the documentary genre, and at mapping out the deeper Agnieszka MORawIN´ska, Hanna WRÓBlewska, Anna TOMCZAK BeRnáthy Zsigmond, SZMOLKA Zoltán | Solid Studio | www.solid.hu újraértelmezését célozzák, a társadalmi folyamatok mélyebb moz- mechanisms of social processes. -

Treating History in the Work of Allan Sekula and Jeff Wall

A Matter of Cleaning up: Treating History in the Work of Allan Sekula and Jeff Wall Hilde Van Gelder This contribution considers two ways of artistically approaching photography today. Comparing a selection of examples from the work of Allan Sekula with some of Jeff Wall’s pictures, it looks at different methods to treat the relationship between the photograph and its caption(s). Furthermore, it investigates diverging attitudes towards the pictorial aspects of the medium. Also, whereas both artists are very much engaged in art critical writing, one can conclude that the interaction between their essays and photoworks is very much opposed. Finally, departing from the analysis of that selective body of images by both artists, which are addressing what can be named an ‘iconography of cleaning up’, two diverging world views and modes of treating history are traced. Keywords: Allan Sekula (b. 1951), Jeff Wall (b. 1946), photography and pictorial autonomy, photographs and captions, portrait photography, photography and art criticism, photography in contemporary art, photographic realism The invisible image and the larger montage Consider a photograph by Allan Sekula that is part of his sequence Titanic’s 1 Wake (1998/2000) (figure 1). Shipwreck and worker, Istanbul shows an image 1 – The sequence has been published in two of a man who is holding a shovel, and who, at first sight, might appear—yet quite different versions: first—and substantially shorter—in Art Journal, 60:2 for no obvious reason—to be deepening a channel running through a very (Summer 2001), 29-37; and secondly, in badly maintained quay. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography The purpose of this bibliography is to indicate a relatively small number of books and articles in English to which the reader unfamiliar with the general orientations of the foregoing essays may refer. In the case of the very extensive writings of Freud and Marx I have indicated 'entry points' of most immediate proximity to the concerns of the essays in this book. Articles of interest published in the journals Screen and Screen Education (London) are too numer ous to list. Unless otherwise stated, the place of publication is London. ALTHUSSER, L., 'Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes towards an investigation', in Lenin and Philosophy and other essays, New Left Books, 1971. BARTHES, R., Mythologies, Paladin, 1973. BARTHES, R., Elements of Semiology, Jonathan Cape, 1976. BARTHES,R., Image-Music-Text, Fontana, 1977. BENJAMIN, w., 'A Short History of Photography', Screen, vol. 13, no 1, Spring 1972. BENJAMIN, W., 'The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Repro duction', in Illuminations, Fontana, 1973. BOURDIEU, P., 'The Aristocracy of Culture' and 'The Production of Belief: Contribution to an Economy of Symbolic Goods', Media, Culture and Society, vol. 2, no. 3, July 1980. BURGIN, V., 'Art, Common-Sense and Photography', Camerawork, 3,1976. BURGIN, V., 'Modernism in the work of Art', 20th Century Studies, 15-16, Canterbury, 1976. COWARD, R. and ELLIS, J., Language and Materialism, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977. 218 Select Bibliography ECO, u., A Theory of Semiotics, Indiana University Press, 1976. ERLICH, V., Russian Formalism: History, Doctrine, Mouton, The Hague, 1965. FOUCAULT, M.,'Las Meninas', in The Order of Things, Tavistock, 1970. -

Christopher Grimes Gallery Is Pleased to Present the Late Allan Sekula's

Santa Monica, March 2014 – Christopher Grimes Gallery is pleased to present the late Allan Sekula’s, Ship of Fools. This series was first shown at the São Paulo Biennial and represents Sekula’s last major body of work. Throughout his career he repeatedly returned to the theme of maritime space through a number of interrelated books, films and exhibitions including Fish Story, TITANIC’s wake and Lottery of the Sea. Ship of Fools examines the adaptation of a cargo vessel in 1998 to host a mobile multi-media exhibition in its hold. The exhibition, sponsored by the International Transport Workers Federation, formed part of an 18-month campaign around the world against a system of shipping under flags of convenience that shield substandard vessels and exploitative labor conditions. Sekula’s participation in various stages of the journey on the Global Mariner resulted in this series of photographs on display. Allan Sekula (1951-2013), photographer, theorist, historian and writer lived and worked in Los Angeles. Sekula’s work is currently included in the Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, NY (2014), and will appear this summer in SITElines, Santa Fe, NM (2014). Recent exhibitions include Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY (2013); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2013); Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2011); and Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest, Hungary (2011). Sekula has participated in the 29th Biennial de São Paulo (2010), documenta 11 and 12 (2002, 2007), and he was the subject of a major retrospective, Performance Under Working Conditions, for the Generali Foundation in Vienna (2003).