Thesis Caroline Bolling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National, 1942

National Louis University Digital Commons@NLU Yearbooks Archives and Special Collections 1942 The aN tional, 1942 National College of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/yearbooks Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Education, National College of, "The aN tional, 1942" (1942). Yearbooks. 56. https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/yearbooks/56 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Digital Commons@NLU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yearbooks by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@NLU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESENTING AN ALBUM OF THE YEAR'S ACTIVITIES AT NATIONAL COLLEGE OF EDUCATION. EVANSTON, ILLINOIS VOL. 27 1942 We present the 1942 National: an appropriately gay and poignant record of events, which were crammed into a year when the word "security" became obsolete and the word "courage" was recoined. As women, we marched not grimly, nor with guns, but steadily, humming a cheerful refrain to keep e times. ADMINISTRATION Edna Dean Baker, President Out of a fabulous stack of names, records, and financial reports, National's administration competently creates an amazing semblance of order to keep the wheels of the college speeding smoothly throughout the year. Daily, the office of administration is confronted with the usual queries regarding matriculation, course of study, and various permissions. In this capacity, the administrators have made National an outstanding school in the educational field and have aided in obtaining for the school the long desired accreditment by the American Associa- tion of Teachers' Colleges. -

Dolphin Films Una Produzione Bieber Time Films & Scooter

DOLPHIN FILMS PRESENTA UNA PRODUZIONE BIEBER TIME FILMS & SCOOTER BRAUN FILMS IN ASSOCIAZIONE CON IM GLOBAL & ISLAND DEF JAM MUSIC GROUP DIRETTO DA JON M.CHU con JUSTIN BIEBER e la speciale partecipazione di SCOOTER BRAUN | USHER RAYMOND IV | JON M. CHU | PATTIE MALLETTE | JEREMY BIEBER | RYAN GOOD | MIKE POSNER | RODNEY JERKINS | ALFREDO FLORES | NICK DEMOURA ...e molti altri! Durata 92 minuti In Italia Believe è distribuito da Nexo Digital e Good Films in collaborazione con i media partner Sky Uno HD, Radio Kiss Kiss, MYmovies.it e Team World. SINOSSI BELIEVE di Justin Bieber regala una visione intima e profonda del tour mondiale dell’artista che ha registrato il tutto esaurito. Non solo vedrete le immagini sbalorditive delle performance dei suoi maggiori successi, ma avrete un biglietto personale per accedere al backstage e scoprire come l’intero tour è stato concepito. Believe garantisce una panoramica esclusiva sulla vita di Justin fuori dal palco ed è un viaggio che ne ripercorre la vita: dagli esordi da perdente che sognava di suonare al Madison Square Garden, fino a diventare la più grande pop star mondiale. “Believe” in Justin Bieber. NOTE DEL REGISTA Ho sempre saputo sin da quando finimmo “Never Say Never” nel 2011, che la storia di Justin Bieber non sarebbe finita. Avevo la sensazione che il capitolo successivo della sua vita sarebbe stato ancora più convincente dell’inizio della sua storia, ma non avrei mai pensato di essere di nuovo io a raccontarlo. Quando, qualche anno dopo, mi arrivò l’invito di Justin a seguirlo in tour per realizzarne un film, presi al volo questa opportunità. -

Corrects Himself, Didn't Meet Mexico Leader

LIFESTYLE THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 2013 Music39 & Movies Spider-Man Broadway musical to close in January, move to Vegas Bieber corrects himself, didn’t meet Mexico leader File photo shows people line up to enter the Foxwoods Theatre for a matinee showing of “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark,” in New York.—AP pider-Man: Turn Off the Dark” will end its The show was also embroiled in legal disputes Broadway run in January, a spokesman said after Tony-winning director Julie Taymor, of “The “Son Monday, and the popular musical is set Lion King,” was fired from the production in March to move to Las Vegas. The show, the most expensive 2011. Taymor reached an agreement with the show’s staged on Broadway, had a rocky start in 2010 with producers this year. The musical, based on one of cast injuries during high-wire stunts and opening Marvel Comic’s most famous heroes, cost more than night delays. $70 million to bring to the stage and includes music “We are excited to report that the next destination by Bono and The Edge. It routinely brings in more for SPIDER-MAN will be the entertainment capital of than $1 million a week at the box office. However, the world: Las Vegas,” Rick Miramontez, a spokesman the Wall Street Journal reported on Monday that the for the show, said in an email to Reuters. The show has been running below its breakeven point Broadway show will close in January, he said, and for weeks, even though it is among the top shows in further details will be announced in the coming attendance figures.—Reuters weeks. -

Virtual Reality Tour

volume 5 issue 10 2012 BRADVirtual Reality PAISLEY Tour In the House with the Thin Lizzy Crew A Gig From Hell With the Twins of Evil: Rob Zombie and Marilyn Manson Warriors of the Road Reunion >>Plus Harness Inside Screens Knows Why Custom Projection Screens are Becoming Increasingly Popular in the USA I mobile production monthly II mobile production monthly “You guys saved the day…we couldn’t have WWW.AIRCHARTERSERVICE.COM done it without you! I’m sure thousands of fans are thanking you as I type” Use your smartphone to scan and watch our corporate video Air Charter Service (ACS) are longstanding experts providing aircraft charter solutions for artist HELICOPTERS management companies and tour managers worldwide - successfully flying equipment, crew TURBOPROPS and some of the world’s most renowned artists on large scale music tours. Our global network PRIVATE JETS of offices are able to provide flexible and bespoke solutions to meet your exact requirements, EXECUTIVE AIRLINERS whatever your aircraft charter needs. COMMERCIAL AIRLINERS Contact us today to see how we can look after your logistical requirements. CARGO AIRCRAFT A GLOBAL LEADER IN MUSIC INDUSTRY CHARTERS N.AMERICA | S.AMERICA | EUROPE | AFRICA | CIS | MIDDLE EAST | ASIA 1 mobile production monthly 2 mobile production monthly volume 5 issue 10 2012 contents IN THE NEWS 10 New Hires 6 Lighting 12 Harness Screens Bandit Clients Dominate at CMA 14 Warriors of the Road Awards Venues Reunion Venues Inside and Out, Harrah’s Sounds 18 BRAD PAISLEY VIRTUAL Good with Community REALITY TOUR: Well Planned and 7 Sound Even Better Executed DiGiCo is in Total Control of 23 Brad Paisley Crew Cirque du Soleil’s MJ World Tour 24 In the House with the Thin Workshops Lizzy Crew 2012 Milos Runs 2012 Safety Work- 28 A Gig from Hell with the shop in China Twins of Evil: Rob Zombie and 8 Special Effects Marilyn Manson Justin Beiber’s “Believe” Tour 32 Obituary Believes in Special Effects from Strictly FX mobile production monthly 3 FROM THE Publisher It is hard to believe that the Country Music Award shows are all here. -

Salvations Highlight LC Revival

September 27, 2018 Volume 133 l Issue No. 19 TO REPORT A NEWS ITEM OR TO BUY AN AD,CALL 318.442.7728 www.baptistmessage.com GBO: Doing more, with a little help from each other By John Kyle Louisiana Baptists Communications ALEXANDRIA (LBM) – How do you reach a culture that is seemingly not interested in you? How can you instill a vision and pas- sion for missions in children? How can you use current commu- nication platforms to seed God’s truth across the state? Brian Blackwell photo How can you bring a once vibrant Paul Taylor of Colyell Baptist Church in Livingston preaches under an evangelism tent to Hondurans moments before they entered congregation back to life? a line to be seen at a medical clinic. According to Missions and Ministries team leader John Hebert, all of the above is possible, “With a lot of help from your friends.” “In the day-in and day-out grind of ministry, it’s easy to forget how large our PRESCRIption HOPE task is,” Hebert said. “If we’re going to make the impact all of us agree needs to be made, we need more individuals par- Honduras medical mission ticipating in the Georgia Barnette State Missions Offering.” dispenses help, God’s love David Hankins, executive director for Louisiana Baptists, echoed this chal- By Brian Blackwell lenge. Message Staff Writer “We have literally hundreds of churches and thousands of our members SANTA CRUZ DE GUAYAPE, Honduras – who do not participate in this crucial of- A young Honduran boy named Christian ap- fering for Louisiana,” said Hankins. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Paul Mccartney – New • Mary J Blige – a Mary

Paul McCartney – New Mary J Blige – A Mary Christmas Luciano Pavarotti – The 50 Greatest Tracks New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI13-42 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921602 Price Code: SPS Order Due: Release Date: October 22, 2013 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 6 02537 53232 2 Key Tracks: ROAR ROAR Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM (DELUXE) Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921502 Price Code: AV Order Due: October 22, 2013 Release Date: October 22, 2013 6 02537 53233 9 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: Key Tracks: ROAR Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM (VINYL) Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921401 Price Code: FB Order Due: October 22, 2013 Release Date: October 22, 2013 6 02537 53234 6 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: Key Tracks: Vinyl is one way sale ROAR Project Overview: With global sales of over 10 million albums and 71 million digital singles, Katy Perry returns with her third studio album for Capitol Records: PRISM. Katy’s previous release garnered 8 #1 singles from one album (TEENAGE DREAM). She also holds the title for the longest stay in the Top Ten of Billboard’s Hot 100 – 66 weeks – shattering a 20‐year record. Katy Perry is the most‐followed female artist on Twitter, and has the second‐largest Twitter account in the world, with over 41 million followers. -

P20-21 Layout 1

Established 1961 21 Lifestyle Music Tuesday, July 2, 2019 Bieber defends manager after Swift ‘bullying’ accusation ustin Bieber accused Taylor Swift of “crossing a line” worked with Kanye West-another artist who has feuded Sunday after she re-ignited their longstanding feud in with Swift in the past. Ja post attacking his manager for buying the rights to “For you to take it to social media and get people to much of her multi-platinum back catalog. Swift said she hate on scooter isn’t fair,” Bieber wrote, posting along- suffered years of “manipulative bullying” at the hands of side an old photo of him and Swift together in the early Scooter Braun, an industry powerhouse whose Ithaca days of their joint rise to pop superstardom. “Seems to Holdings recently bought Big Machine Label Group, me like it was to get sympathy u also knew that in post- which produced Swift’s first seven albums. ing that your fans would go and bully scooter.” Swift’s “Essentially, my musical legacy is about to lie in the huge social media presence is backed up by legions of hands of someone who tried to dismantle it,” Swift wrote, fiercely loyal fans-known as “Swifties”-who frequently claiming she had never been offered the chance to buy round on those perceived as slighting her. “I feel like the the rights to her back catalog, which includes “Fearless” only way to resolve conflict is through communication,” and “1989”. “Never in my worst nightmares did I imagine Bieber wrote. “So banter back and forth online i don’t the buyer would be Scooter,” she wrote Sunday, signing believe solves anything.” — AFP off “Sad and grossed out.” Canadian superstar Bieber In this file photo Taylor Swift attends the 2019 Billboard In this file photo singer Justin Bieber performs during his took to Instagram to defend Braun, a music industry Music Awards at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, “Believe” tour at The Staples Center in Los Angeles, powerhouse who also manages Ariana Grande and has Nevada. -

Among the Mormons in the Days of Brigham Young by Wilfred H

AMONG THE MORMONS IN THE DAYS OF BRIGHAM YOUNG BY WILFRED H. MUNRO TN 1871 the author of this paper was told by his •^ physician that he must throw up his position and go west for a "life in the open" or he could not live six months. He was then a Master in a military board- ing school, and one of his pupils happened to be a brother-in-law of Bishop Tuttle of Utah. Like all young men of that day "Mormonism" appealed to him as a curiosity. He chose Salt Lake City as a place from which to wander and has ever since rejoiced in the experiences resulting therefrom. The stories of the beginnings of a religion are ordi- narily vague and of doubtful value. Accounts written, as in the case of the Mohammedans, upon "palm leaves, skins, blade-bones and the hearts of men," do not always agree in their statements and can never be entirely satisfactory. It is not so with "Mormon- ism." Its founder, Joseph Smith, was born hardly a century and a quarter ago (1805); its organization is not yet a hundred years old (1830). An alert printing press has steadily kept us informed of all that is worth knowing in its history. The establishment of the Mormon state in what was supposed to be foreign territory, in 1847, does not antedate the birth of many members of this Society. (It was not until 1848 that Mexico, by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ceded to the United States the indefinite and unsurveyed regions of the provinces of New Mexico and Upper California.) Very many living men have known the great leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. -

LSA Template

CONCERTS Copyright Lighting&Sound America January 2013 http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.html Belief Systems A top design team pulls out all the stops for Justin Bieber’s Believe Tour By: Sharon Stancavage 44 • January 2013 • Lighting&Sound America The far left and right LED screens are often used for full-body IMAG of the singer. At times, they take on the feel of a full-length mirror, says Nick Jackson, of Chaos Visual Productions, the video gear supplier from Los Angeles. he phenomenon that is sophomore effort, the situation first outing, My World Tour, and were Justin Bieber can be easily changed considerably. “This time all integral to the creative meetings. summarized by the voice around, Justin wanted to involve New to the Bieber team is Jon M. of an anonymous woman— other people whom he had grown Chu, who directed Never Say Never not a girl—on a YouTube fond of in his time on the road, as and serves as creative director while T video of the opening of the well as several individuals involved in Marzullo continues as production star’s current Believe Tour. his film [Never Say Never],” Marzullo designer and tour production As a barrage of effects is unleashed explains. The list of collaborators manager. Other key members of the before Bieber’s appearance on stage, also included many of his vendors: team are Chu’s associates Cristobal a woman says, in a voice awash with staging suppliers Brian White, of Valecillos and Isabel Aranguren. The awe and amazement, “Oh, my God.” Burbank-based Show Group directive for the show’s theme came It’s only the first few moments of the Production Services (SPGS), and straight from Bieber. -

30 Sep 2011 (ISSUE of HK$50 MILLION CONVERTIBLE BONDS

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in doubt as to any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should consult your stockbroker or other registered dealer in securities, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in TLT Lottotainment Group Limited (the “Company”), you should at once hand this circular together with the accompanying form of proxy to the purchaser or the transferee or to the bank, stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser or the transferee. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. TLT LOTTOTAINMENT GROUP LIMITED 彩娛集團有限公司 (Incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability) (Stock Code: 8022) ISSUE OF HK$50 MILLION CONVERTIBLE BONDS AND PROPOSED SHARE CONSOLIDATION AND CHANGE IN BOARD LOT SIZE AND NOTICE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL MEETING AND PROPOSED APPOINTMENT OF DIRECTOR A notice convening an extraordinary general meeting of the Company (the “EGM”) to be held at Room A, 9th Floor, Fortis Tower, 77-79 Gloucester Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong on Tuesday, 18 October 2011 at 11:30 a.m. is set out on pages 29 to 31 of this circular. -

Kingdom Worker Connection Via Email, Please Contact [email protected]

Kingdom DECEMBER 2018 A PUBLICATION OF Worker THE MINISTRY OF CHRIST IN YOUTH Connection WWW.CIY.COM 2 STAFF LIST CIY PRESIDENT ANDY HANSEN [email protected] EDITOR CHRIS ROBERTS [email protected] ASSISTANT EDITOR AUDREY WUNDERLICH [email protected] STAFF WRITER BECCA HAINES [email protected] ART DIRECTOR AUSTIN EIDSON [email protected] CONTRIBUTING WRITERS/DESIGNERS/PHOTOGRAPHERS CRAIG DAVENPORT, MATT FOREMAN, MARK NEUENSCHWANDER, MARK RANKIN, ELLEN SMITH COVER PHOTO BY AUDREY WUNDERLICH SUBSCRIPTIONS P.O. BOX B JOPLIN, MO 64802 (888) 765-4CIY To be added to the CIY mailing list, or to receive the Kingdom Worker Connection via email, please contact [email protected] KINGDOM WORKER CONNECTION 3 KINGDOM WORKER CONNECTION CONTENTS STAFF LIST 2 PRESIDENT’S LETTER ANDY HANSEN 4 A 50th ANNIVERSARY STORY 6 OVERCOMING OBSTACLES SUPERSTART 8 BECOMING A NINJA WARRIOR 12 UNDERSTANDING THE CHAOS OF JR. HIGH 14 5.2 THINGS YOU DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT KJ-52 18 GOD-SIZED DREAMS 20 MISSIONS IS A LIFESTYLE ENGAGE 26 STANDING FOR JESUS MOVE 30 STORIES FROM THE ROAD ENGAGE 32 SOCIAL MEDIA SPOTLIGHT 33 FINAL THOUGHTS SCOTT WALKER 34 CIY PROGRAMS 35 CHRIST IN YOUTH 4 PRESIDENT’S LETTER ou are very important to Christ In Youth. As president, I want to let you in on five important facts about CIY. 1. God continues to show His favor in the events, tripsY and resources CIY is providing in its partnership with the local church. This past summer more than 46,000 young people and their adult leaders attended 58 MOVE high school weeks or MIX junior high events, and hundreds more went on an Engage mission trip. -

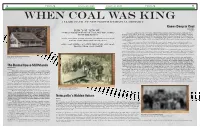

The Baima House Still Stands Newcastle's Hidden Voices Knees

14 Focus MARCH 20, 2020 MARCH 20, 2020 Focus 15 When Coal Was King A look back at Newport’s Regional History Knees Deep in Coal SHANA HUANG Did you know... Reporter Over 10 Million tons of coal was excavated In 1996, a book titled: The Coals of Newcastle: A Hundred Years of Hidden History was published, detailing the city of from the region Newcastle’s unique history. From 1863 to 1870, Seattle was famous throughout the country for a string of bustling coal mining towns from Bellingham to Carbonado. Included in this line of towns was Newcastle, the most prosperous and advanced town of them all. Founded in 1869, Newcastle was created as a coal-mining town, and the abundance and quality of the coal in Newcastle Coal was the first product shipped out of brought about economic growth for Seattle, a city which had been trying to find other products besides lumber and pilings to bring the fledgling port of seattle income to the port. Phillip H. Lewis, a man from Illinois, described how there were coal outcroppings in the area during 1863, and a team quickly assembled in search of coal, consisting of Lewis himself, Edwin Richardson, a teacher who surveyed school land, and old coal mines can still be found on local Josiah Settle, who served as a tree-cutter. After five weeks of combing through the forest, the group found coal outcroppings along trails near coal creek riverbanks, exciting the new businessmen of Seattle. Once their discovery was made, Edwin Richardson named the brook “Stone Coal Creek,” and thus the name “Coal Creek” was forever cemented in history.