Tone Glow, June 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Year in Review

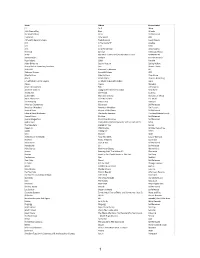

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Detroit's Maritime Techno Underground

Detroit’s maritime techno underground. On the relationship between the 18th century pirates movement and concepts of social utopias, ideology, and cultural production in Detroit techno. A proseminar-paper for PS Cultural and Media Studies, course title: Pirates in (US-)American Culture, conducted by Mag.a Dr.in Alexandra Ganser, WS 2014/2015, by Christian Hessle, matriculation number: 9450392, e-mail: [email protected] due to 1 March 2015, 3676 words. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................3 2. Double consciousness....................................................................................................3 3. The black Atlantic..........................................................................................................4 4. The ancestors of Detroit techno: Funk, Fusion Jazz, and Afrofuturism........................5 5. The Belleville Three......................................................................................................6 6. The factory: from the ship to the city............................................................................6 7. Underground Resistance................................................................................................7 8. Drexciya.......................................................................................................................10 9. Conclusion...................................................................................................................12 -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Contortions to Match Your Confusion: Digital Disfigurement and the Music of Arca

Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas ISSN: 0890-5762 (Print) 1743-0666 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrev20 Contortions to Match Your Confusion: Digital Disfigurement and the Music of Arca Wayne Marshall To cite this article: Wayne Marshall (2015) Contortions to Match Your Confusion: Digital Disfigurement and the Music of Arca, Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas, 48:1, 118-122, DOI: 10.1080/08905762.2015.1021112 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08905762.2015.1021112 Published online: 30 Apr 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 175 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrev20 Download by: [Berklee College of Music] Date: 03 November 2015, At: 07:17 Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas, Issue 90, Vol. 48, No. 1, 2015, 118–122 Contortions to Match Your Confusion: Digital Disfigurement and the Music of Arca Wayne Marshall An assistant professor at Berklee College of Music, Wayne Marshall is an ethnomusicologist who studies the interplay between Caribbean and American music, sound reproduction technologies, and musical publics. He co-edited Reggaeton (2009) and has published in such journals as Popular Music, Callaloo, and The Wire, as well as his critically acclaimed blog, wayneandwax.com. “Día de los Muertos,” a mix released in late October 2014 by Houston’s Svntv Mverte (aka Santa Muerte), a DJ duo with a name invoking “Mexico’s cult of Holy Death, a reference to the worship of an underground goddess of death and the dead,”1 opens with an ominous, 1 Marty Preciado, “Meet arresting take on reggaeton. -

Discographie

Discographie I. Précurseurs musiques savantes Compilations An Anthology Of Noise & Electronic Music, Vol. 1-5 (Sub Rosa, 2000-2007) Le bruit dans la musique 1900-1950 Compilations Dada et la musique (Centre Georges Pompidou/A&T, 2005) Futurism & Dada Reviewed 1912-1959, (Sub rosa, 1995) Musica Futurista : The Art Of Noise (LTM, 2005) George Antheil, Ballet mécanique, dirigé par Daniel Spalding (Naxos, 2001) Belà Bartók, Le mandarin merveilleux, dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1997) John Cage, Sonatas And Interludes For Prepared Piano, interprété par Boris Berman (Naxos, 1999) John Cage, Imaginary Landscapes, dirigé par Jan Williams (Hat Hut, 1995) Henry Cowell, New Music : Piano Compositions By Henry Cowell, interprété par Sorrel Hays, Joseph Kubera, Sarah Cahill (New Albion Records, 1999) Charles Ives, Symphony n°2 etc., dirigé par Léonard Bernstein (Deutsche Grammophon, 1990) Erik Satie, Parade, dirigé par Manuel Rosenthal (Ades, 2007) Arnold Schoenberg, Pierrot lunaire, Lied der Waldtaube, Erwartung dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Sony, 1993) Edgard Varese, The Complete Works, dirigé par Riccardo Chailly (Decca, 1998) Musique et timbre, 1950 à nos jours Luciano Berio, Differences, Sequenzas III & VII, Due pezzi, Chamber Music (Lilith, 2007) György Ligeti, Requiem, Aventures, Nouvelles Aventures (Wergo, 1985) György Ligeti, Chamber Concerto, Ramifications, String Quartet n°2, Aventures, Lux aeterna, dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1983) Tristan Murail, Gondwana, Désintégrations, Time and Again (Disques Montaigne, 2003) Giacinto Scelsi, The Orchestral Works 2 (Mode, 2006) Krzysztof Penderecki, Anaklasis, Threnody, etc., dirigé par Wanda Wilkomirska (EMI, 1994) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Aus den sieben Tagen (Harmonia Mundi, 1988) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Stimmung (Hyperion, 1986) Iannis Xenakis, Orchestral Works, Vol. -

Detroit: Techno City 27 July – 25 September 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Preview 26 July

ICA Press release: 26 May 2016 Detroit: Techno City 27 July – 25 September 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Preview 26 July Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit (1988). Courtesy Neil Rushton and 10 Records LTD The next ICA Fox Reading Room exhibition will present a studied look at the evolution and subsequent dispersion of ‘Detroit Techno music’. This term, coined in the late 1980s, reflects the musical and social influences that informed early experiments merging sounds of synth-pop and disco with funk to create this distinct music genre. For the first time in the UK, a dedicated exhibition will chart a timeline of ‘Detroit Techno music’ from its 1970s origins, continuing through to the early 1990s. The genre’s origins begin in the disco parties of Ken Collier with influence from local radio stations and DJs, such as Electrifying Mojo and The Wizard (aka Jeff Mills). The ICA’s exhibition explores how a generation was inspired to create a new kind of electronic music that was evidenced in the formative UK compilation: Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit. Using inexpensive analogue technology, such as the Roland TR 808 and 909, DJs and producers including Juan Atkins, Blake Baxter, Eddie Fowlkes, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson, formed this seminal music genre. Although the music failed to gain mainstream audiences in the U.S, it became a phenomenon in Europe. This success established Detroit Techno, as a new strand of music which absorbed exterior European tastes and influences. This introduced a second wave of DJs and producers to the sound including Carl Craig, Richie Hawtin and Kenny Larkin. -

House, Techno & the Origins of Electronic Dance Music

HOUSE, TECHNO & THE ORIGINS OF ELECTRONIC DANCE MUSIC 1 EARLY HOUSE AND TECHNO ARTISTS THE STUDIO AS AN INSTRUMENT TECHNOLOGY AND ‘MISTAKES’ OR ‘MISUSE’ 2 How did we get here? disco electro-pop soul / funk Garage - NYC House - Chicago Techno - Detroit Paradise Garage - NYC Larry Levan (and Frankie Knuckles) Chicago House Music House music borrowed disco’s percussion, with the bass drum on every beat, with hi-hat 8th note offbeats on every bar and a snare marking beats 2 and 4. House musicians added synthesizer bass lines, electronic drums, electronic effects, samples from funk and pop, and vocals using reverb and delay. They balanced live instruments and singing with electronics. Like Disco, House music was “inclusive” (both socially and musically), infuenced by synthpop, rock, reggae, new wave, punk and industrial. Music made for dancing. It was not initially aimed at commercial success. The Warehouse Discotheque that opened in 1977 The Warehouse was the place to be in Chicago’s late-’70s nightlife scene. An old three-story warehouse in Chicago’s west-loop industrial area meant for only 500 patrons, the Warehouse often had over 2000 people crammed into its dark dance foor trying to hear DJ Frankie Knuckles’ magic. In 1982, management at the Warehouse doubled the admission, driving away the original crowd, as well as Knuckles. Frankie Knuckles and The Warehouse "The Godfather of House Music" Grew up in the South Bronx and worked together with his friend Larry Levan in NYC before moving to Chicago. Main DJ at “The Warehouse” until 1982 In the early 80’s, as disco was fading, he started mixing disco records with a drum machines and spacey, drawn out lines. -

Tõmbas Kor- Rammile Ja Ruumilahendustele Maailma Kontekstis Samuti Rikkalik

SUVE ERILEHT 2018 2 : SUVE ERILEHT 2018 JUHTKIRI SILLERDAV SUVI JA SÜÜTUNDE SURM Pidulike marsihelide saatel astus UFOst kivile Võlur ja teatas: „Mul on teile kõigile tähtis uudis – meie piirkonda on tabanud igavene suvi!” (Tõnu Trubetsky ja Juhan Habicht „Igavene suvi”, Vikerkaar 1/1990) Mõned head aastad tagasi esitles maestro Rein Veidemann oma sed söövad su ära. Selles sektoris raha liigub, Valdur Mikita olgu vast valminud raamatut „101 eesti kirjandusteost”. Esitlus koosnes õnnistatud, ja asi seegi. Eesti majandus peab suvele vastu. minu ja Reinu vestlusest ning muidugi tuli kõne alla autori töömee- tod, sest kuulajad tahavad ju väga teada, kuidas kirjanik kirjutab. SUVI KUI MEIE SAKURA Isand Veidemann rääkis talle omasel eksalteeritud moel, kuidas põhi- Sarnaselt iga teise aastaajaga on suvi ja selle tajumine personaalne, osa sellest raamatust valmis nõnda, et ta istus kaunil ja ülikuumal see tähendab, et suve olemuse määrab vaatleja. Kui vaatleja on vin- suvekuul oma kodukabinetis aluspesu väel ja muudkui kirjutas. Kõi- gus, on suvi vingus, kui vaatleja on õnnelik, on suvi õnnelik. Kahjuks gile esitlusel viibijatele tuli see pilt elavalt silme ette ja suvi kui sel- painab personaalsust nüüd line omandas uue värvingu, millest ei puudunud teatud kuumvalk- isegi suurem kollektiviseeri- SUVEJUHTKIRI jad alatoonid. mine kui kolhooside rajami- Suvi on idee kohaselt aasta kauneim aeg, aga idee ja praktika ei se aegu, mistap pole kerge käi alati kokku. „Suvi, sillerdav suvi, lõputult pikk on päev, kauaks jääda avalikult iseendaks ja nõnda nüüd jälle jääb. Suvi, vallatu suvi, laotuses väike naer, nüüd on oma isikliku suvetunde loo- rõõmudeks antud aeg,” laulis kunagi Jaak Joala ja me ju kõik teame, jaks. -

Detroit : Techno

Until recently, Detroit has not had much attention at all con cerning its role as the birthplace of techno. "Detroit, globally known as the birthplace of techno, is virtually unrecognized nationally and locally beyond its Motown and rock roots". It DETROIT: TECHNO has always existed as such under the popular culture radar. First and foremost, why was Detroit the breeding ground for techno music? Why has the general population taken so long in recognizing Detroit for its techno accomplishments? Could it be simply because Detroit is not a mega-city like New York or Los Angeles? Or is it simply because the time and the place ]ohnathan Bowen were not right until recently? The Belleville 3: Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Detroit has long been known by many names: Motown, the Saunderson, arc the three individuals who are credited as Motor City, Hockey Town, and even the less than flattering techno's creators. These three individuals grew up in Murder City. However, with the passing of time and the dim Belleville, hence the term "The Belleville 3," but they later ming and brightening of trends, Detroit would come to be moved into Detroit to carry on their pioneering work in the known by another name: TechnoTown. \Vhat is techno? Upon 1980's and beyond. Atkins, May, and Saunderson didn't actu opening an Encyclopedia Britannica and looking under the ally begin this pioneering work of creating techno in Detroit entry labeled "Techno," one will find this encompassing and however. Juan Atkins sums it up best: "vVhen I first started revealing definition: making music, I lived in Detroit. -

Clever Children: the Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music?

Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music Author Carter, David Published 2009 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland Conservatorium DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1356 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367632 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music? David Carter B.Music / Music Technology (Honours, First Class) Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy 19 June 2008 Keywords Contemporary Music; Dance Music; Disco; DJ; DJ Spooky; Dub; Eight Lines; Electronica; Electronic Music; Errata Erratum; Experimental Music; Hip Hop; House; IDM; Influence; Techno; John Cage; Minimalism; Music History; Musicology; Rave; Reich Remixed; Scanner; Surface Noise. i Abstract In the late 1990s critics, journalists and music scholars began referring to a loosely associated group of artists within Electronica who, it was claimed, represented a new breed of experimentalism predicated on the work of composers such as John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Steve Reich. Though anecdotal evidence exists, such claims by, or about, these ‘Clever Children’ have not been adequately substantiated and are indicative of a loss of history in relation to electronic music forms (referred to hereafter as Electronica) in popular culture. With the emergence of the Clever Children there is a pressing need to redress this loss of history through academic scholarship that seeks to document and critically reflect on the rhizomatic developments of Electronica and its place within the history of twentieth century music. -

Carl Craig Reassembles Tribe

Carl Craig reassembles Tribe Published / Tuesday, 18 August 2009 09:00 AM Words / Resident Advisor Category / Music News Comments / 1 Comment Latest News • Tuesday, 18 Aug 2009 • Music News Carl Craig has announced details of yet another project in which he's lent his production hand, Tribe. A jazz record in the truest sense of that word, Tribe Rebirth, will see the quartet of Phil Ranelin, Wendell Harrison, Marcus Belgrave and Doug Hammond recreating tunes from their past as well as a number of new compositions. The group, which first assembled in the '70s, and issued a slew of LPs that have grown in stature over the years among jazz aficionados, was put back in contact in 2007 when Craig asked Wendell Harrison to be a part of a gig he was putting together in Paris. Craig had previously worked with Belgrave on his Detroit Experiment record, and covered Tribe's "Space Odyssey," but it was his talks with the saxophonist that helped bring the group back together. Craig says that the record, which will see the light of day on Community Projects, is "less experimental than Innerzone Orchestra and more cohesive than Detroit Experiment." Tracklist 01. Living In A New Day 02. Glue Fingers 03. Denekas Chant 04. Vibes From The Tribe 05. Son Of Tribe 06. Jazz On The Run 07. Ride 08. Lesli 09. 13th And Senate 10. Where Am I (Featuring Joan Belgrave) Community Projects will release Tribe Rebirth on October 6th, with an iTunes pre-release scheduled for August 25th. Myspace preview: Tribe Detroit More on Carl Craig Marcus Belgrave Trumpet, flugelhorn, vocals Born June 12, 1936, in Chester, Penn.