Peer Reviewed Commentary Journal Article Citation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

They Have Names, Too: a Case Study on the First Five Victims of the Green River Killer: Examining the Construction of Society and Its Creation of Victim Availability

Seattle University ScholarWorks @ SeattleU Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies 2020 They Have Names, Too: A Case Study on the First Five Victims of the Green River Killer: Examining the Construction of Society and Its Creation of Victim Availability Natalie V. Castillo Seattle University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/wgst-theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Castillo, Natalie V., "They Have Names, Too: A Case Study on the First Five Victims of the Green River Killer: Examining the Construction of Society and Its Creation of Victim Availability" (2020). Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses. 2. https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/wgst-theses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. They Have Names, Too: A Case Study on the First Five Victims of the Green River Killer: Examining the Construction of Society and Its Creation of Victim Availability Natalie V. Castillo Seattle University 13 June 2020 Bachelor of Arts in Criminal Justice with Departmental Honors Bachelor of Arts in Women and Gender Studies with Departmental Honors Castillo: FIRST FIVE VICTIMS OF THE GREEN RIVER KILLER 2 Table of Contents I Acknowledgments -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Murder of Marcia King

Murder of Marcia King It was always assumed that Marcia King was possibly one of the first victims of Joseph D Benasutti of Miami County, Ohio. Benasutti has been incarcerated since 1995 for involuntary manslaughter, kidnapping, gross abuse of a corpse, felonious assault, and a litany of other charges. What I found interesting was Marcia King's connection to Louisville, Kentucky. Benasutti was accused of a murder, which he denied, of Peggy Casey in 1994 in Covington, Kentucky. permalink. embed. "They were hopeful Marcia was going to come home, however they're learning at this date that that's not going to happen," Lord said. Lord appealed to anyone who may have information to come forward. He said police believe King was in Louisville and Pittsburgh in March 1981, the month before her murder. Police say she was never reported as a missing person. He declined to give further information, citing an active homicide investigation. Now Marcia has her name back, the hope is that her killer can be found too. DNA Doe Project are seeking donations, but they also want people to submit their genetic info from previous tests to see if they can find matches. This is how they found relatives of Marcia, and were able to help get her positively identified. They're working on the Lyle Stevik case too, amongst others( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lyle_Stevik ). Unsolved and Doe cases are kind of an obsession of mine. Its fucking tragic that so many people die nameless, and so many families are left without answers. I'm so all about me: Murder of Marcia King - ⦠12/04/2018 · On an episode of Unsolved Mysteries, the case was briefly detailed along with several other cases connected to the unidentified serial killer. -

Public Notices & the Courts

PUBLIC NOTICES B1 DAILY BUSINESS REVIEW MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2021 dailybusinessreview.com & THE COURTS BROWARD PUBLIC NOTICES BUSINESS LEADS THE COURTS WEB SEARCH FORECLOSURE NOTICES: Notices of Action, NEW CASES FILED: US District Court, circuit court, EMERGENCY JUDGES: Listing of emergency judges Search our extensive database of public notices for Notices of Sale, Tax Deeds B5 family civil and probate cases B2 on duty at night and on weekends in civil, probate, FREE. Search for past, present and future notices in criminal, juvenile circuit and county courts. Also duty Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. SALES: Auto, warehouse items and other BUSINESS TAX RECEIPTS (OCCUPATIONAL Magistrate and Federal Court Judges B14 properties for sale B7 LICENSES): Names, addresses, phone numbers Simply visit: CALENDARS: Suspensions in Miami-Dade, Broward, FICTITIOUS NAMES: Notices of intent and type of business of those who have received https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/public-notices/ and Palm Beach. Confirmation of judges’ daily motion to register B13 business licenses B2 calendars in Miami-Dade B14 To search foreclosure sales by sale date visit: MARRIAGE LICENSES: Name, date of birth and city FAMILY MATTERS: Marriage dissolutions, adoptions, https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/foreclosures/ DIRECTORIES: Addresses, telephone numbers, and termination of parental rights B8 of those issued marriage licenses B2 names, and contact information for circuit and CREDIT INFORMATION: Liens filed against PROBATE NOTICES: Notices to Creditors, county -

Sounding the Last Mile: Music and Capital Punishment in the United States Since 1976

SOUNDING THE LAST MILE: MUSIC AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE UNITED STATES SINCE 1976 BY MICHAEL SILETTI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jeffrey Magee, Chair and Director of Research Professor Gayle Magee Professor Donna A. Buchanan Associate Professor Christina Bashford ABSTRACT Since the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed the legality of the death penalty in 1976, capital punishment has drastically waxed and waned in both implementation and popularity throughout much of the country. While studying opinion polls, quantitative data, and legislation can help make sense of this phenomenon, careful attention to the death penalty’s embeddedness in cultural, creative, and expressive discourses is needed to more fully understand its unique position in American history and social life. The first known scholarly study to do so, this dissertation examines how music and sound have responded to and helped shape shifting public attitudes toward capital punishment during this time. From a public square in Chicago to a prison in Georgia, many people have used their ears to understand, administer, and debate both actual and fictitious scenarios pertaining to the use of capital punishment in the United States. Across historical case studies, detailed analyses of depictions of the death penalty in popular music and in film, and acoustemological research centered on recordings of actual executions, this dissertation has two principal objectives. First, it aims to uncover what music and sound can teach us about the past, present, and future of the death penalty. -

EXPLOITATION Or! Tchildren,' COMMIT/Fee on the JUDICIARY

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. -~ ~- -.------- EXPLOITATION Or! tCHILDREN,' ('.t . HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON JUVENILE JUSTICE OF THE COMMIT/fEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SEN ATE NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON PROBLEMS OF EXPLOITED CHILDREN NOVEMBER 5, 1981 Serial N 00 J-97 -78 lnted for the use {)f the Committee on the Judiciary ; ': , . U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE W ASmNGTON : 1982 CONTENTS OPENING STATEMENT tr Page Specter, Hon. Arlen, a U.S. Senator from the State of Pennsylvania chair- man, Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice .................................................... : .......... .. 1 CHRONOLOGICAL LIS'r OF WITNESSES COMMI'ITEE ON THE JUDICIARY Rabun, John B., manager, Exploited Child Unit, Jefferson County, Ky., De- partment of Human Services ...................................................................................... 2, 59 [97th Congress] David .................................................................................................................................. 5 STROM THURMOND, South Carolina, Chairman Sullivan, Terry, former prosecutor for the State of Illinois .................................... 17 CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, JR., Maryland JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware Rittet:, Father Bruce, fo~nder a~d president, Covenant House, New York City. 27 PAUL LAXALT, Nevada EDWARD M. KENNED~, ~a~s~chusetts Pregha~co, .Ronald J., VIce chaIrman, Jefferson County Task Force on Child ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah ROBERT C. BYRD, West VIrgInIa. ProstItutIon -

The Commercialization of Crime Solving: Ethical Implication of Forensic Genetic Genealogy

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 5-6-2021 The Commercialization of Crime Solving: ethical implication of forensic genetic genealogy Hannah Lee University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Privacy Law Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Hannah, "The Commercialization of Crime Solving: ethical implication of forensic genetic genealogy" (2021). Honors Theses. 1568. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1568 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Commercialization of Crime Solving: ethical implications of forensic genetic genealogy by Hannah Lee Honors Thesis Submitted to: Jepson School of Leadership Studies University of Richmond Richmond, VA May 6, 2021 Advisor: Dr. Terry Price Abstract The Commercialization of Crime Solving: ethical implication of forensic genetic genealogy Hannah Lee Committee members: Dr. Terry Price, Dr. Jessica Flanigan, and Dr. Lauren Henley With the advancement of DNA technology and expansion of direct-to-consumer DNA services, a growing number of cold cases have been solved using a revolutionary new investigative method: familial DNA mapping. While the technique has been lauded by law enforcement as revolutionizing criminal identification, others are concerned by the privacy implications and impact on the family structure. In this thesis I will draw on communitarian, liberal rights, utilitarian, and social justice arguments for and against the practice. I conclude that this method has the potential to increase security and provide justice for victims and families, but absent comprehensive regulation and privacy protections, serves as a threat to autonomy and privacy rights. -

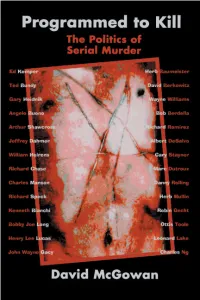

Programmed to Kill

PROGRAMMED TO KILL PROGRAMMED TO KILL The Politics of Serial Murder David McGowan iUniverse, Inc. New York Lincoln Shanghai Programmed to Kill The Politics of Serial Murder All Rights Reserved © 2004 by David McGowan No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com ISBN: 0-595-77446-6 Printed in the United States of America This book is for all the survivors. “This man, from the moment of conception, was programmed for murder.” —Attorney Ellis Rubin, speaking on behalf of serial killer Bobby Joe Long Contents Introduction: Mind Control 101 ................................................xi PART I: THE PEDOPHOCRACY Chapter 1 From Brussels… ......................................................3 Chapter 2 …to Washington ....................................................23 Chapter 3 Uncle Sam Wants Your Children ............................39 Chapter 4 McMolestation ......................................................46 Chapter 5 It Couldn’t Happen Here ........................................54 Chapter 6 Finders Keepers ......................................................59 PART II: THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT HENRY Chapter 7 Sympathy for the Devil ..........................................71 Chapter 8 Henry: -

Judge Grants DNA Testing in 1987 Murder Case

Public Records & Notices Monitoring local real estate since 1968 View a complete day’s public records Subscribe Presented by and notices today for our at memphisdailynews.com. free report www.chandlerreports.com Friday, September 18, 2020 MemphisDailyNews.com Vol. 135 | No. 127 Rack–50¢/Delivery–39¢ Empty chairs, stage demonstrate problems for live-events industry TOM BAILEY a stage dotted the vast, riverside celebrations, concerts and other led the local part of a national, the 6-month-old Live Events Courtesy of The Daily Memphian lawn Tuesday afternoon, Sept. face-to-face activities for crowds. “Empty Event” effort. Coalition. Those strolling through Tom 15.The answer: No one. That means the 12 million peo- Similar “Empty Event” dis- The purpose of the “Empty Lee Park might have wondered Which was the point of “Emp- ple who earn a living setting up plays have happened or are Event” spectacles is not only to who would be hosting the fancy ty Event,” a combination of stage events, securing them, entertain- planned in New York City, Wash- bring attention to how COV- outdoor event. Forty-eight ta- craft, pop-up public art and press ing for them and decorating them ington, D.C., Boston, San Di- ID-19 has crushed the live-events bles with centerpieces and table conference. Practically no one are struggling to find work. ego, Texas, Kentucky and Den- clothes, 384 seats, two bars and is staging business meetings, Memphis-based LEO Events ver, all under the umbrella of EMPTY CONTINUED ON P2 DNA testing of crime scene evidence that includes a knife used in the murders, eyeglasses, and blood- Judge grants DNA testing in stained items such as a washcloth, clothing of Payne and the victims, curtains, a rug, stuffed animals and a tampon. -

No Body Murder Cases

“No-body” Murder Trials in the United States© By Thomas A. (Tad) DiBiase, No Body Guy www.nobodymurdercases.com Through November 1, 2020 (542 trials) (50 states, DC, Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands); (Approximately 71 dismissals, mistrials, acquittals or reversals on appeal for conviction rate of approximately 86%, conviction for all murder cases is 70% according to Bureau of Justice Statistics); (Approximately 31 death penalty cases); (91% of cases involve male defendants with 58% of the victims being female); (at least 52% (268 cases) were domestic violence cases, generally a man killing a woman); (17% (90 cases) had victims under 18 years old, generally children of defendants)1 For three cases of alleged “innocent” men being convicted see Boorn, Jesse (also oldest case), Louise Butler/George Yelder and Hudspeth, Andrew. Also, a case handled by Abe Lincoln: Trailor brothers. Defendant’s Victim’s Name Trial Location Result Date Abbott, Joel Carolann March Oregon Convicted of August 1985 Terrence Payne 1993 murder. Abercrombie, Hoyle Smith Feb. Lee County, Convicted of 1st degree Donald Lewis and Margie 17, NC murder for Nov. 4, 1995 Shaw 1997 killings, defendant said he buried bodies in woods near Spring Lake but never found. Sentenced to life. Adams, Robert Mayse, 1988 Alexander Mayse (victim’s wife) and Hobart, 19 yo County, Adams testify against Mayse, Lori North Ward and all three and Estil Ward Carolina convicted. Body allegedly thrown in dumpster. Ward may have practiced Satanism. Abney, Tricia Justin Barnett Septe Jefferson Cou Defendant found guilty of mber nty, Alabama stabbing victim in 1995. 2017 Sentenced to life without possibility of parole. -

ABSTRACT TRUE CRIME DOES PAY: NARRATIVES of WRONGDOING in FILM and LITERATURE Andrew Burt, Ph.D. Department of English Norther

ABSTRACT TRUE CRIME DOES PAY: NARRATIVES OF WRONGDOING IN FILM AND LITERATURE Andrew Burt, Ph.D. Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2017 Scott Balcerzak, Director This dissertation examines true crime’s ubiquitous influence on literature, film, and culture. It dissects how true-crime narratives affect crime fiction and film, questioning how America’s continual obsession with crime underscores the interplay between true crime narratives and their fictional equivalents. Throughout the 20th century, these stories represent key political and social undercurrents such as movements in religious conservatism, issues of ethnic and racial identity, and developing discourses of psychology. While generally underexplored in discussions of true crime and crime fiction, these currents show consistent shifts from a liberal rehabilitative to a conservative punitive form of crime prevention and provide a new way to consider these undercurrents as culturally-engaged genre directives. I track these histories through representative, seminal texts, such as Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy (1925), W.R. Burnett’s Little Caesar (1929, Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me (1952), and Barry Michael Cooper’s 1980s new journalism pieces on the crack epidemic and early hip hop for the Village Voice, examining how basic crime narratives develop through cultural changes. In turn, this dissertation examines film adaptations of these narratives as well, including George Stevens’ A Place in the Sun (1951), Larry Cohen’s Black Caesar (1972), Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me (2010), and Mario Van Peeble’s New Jack City (1991), accounting for how the medium changes the crime narrative. In doing so, I examine true crime’s enduring resonance on crime narratives by charting the influence of commonly overlooked early narratives, such as execution sermons and murder ballads.