THE AFTERMATH of the ANGLO-BOER WAR the Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAY, 1902. MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW. Zuela

MAY,1902. MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW. 269 zuela, under date of June 30, 1902, wrote regarding the un. servers thought that the sky was cloudy and that there was a possibility of rain, but closer observation revealed the fact that what seemed to be usual appearance of the sky at sunrise and sunset since th6 murky, low-hanging clouds was in reality a veil of dust hanging between Mount Pelee eruption, the sky near the horizon being colored heaven and earth. Along toward evening the setting sun reddened this red, and the sun having a greenish hue. Also during the day: cloud and gave it the appearance of coming from a distant flre. and especially in the forenoon, a large ring of prismatic colors Rev. Robert C. Caswell writes from Stroudsburg, Pa., as fol- surrounded the sun; and the heavens, which shoulcl be deel lows: blue, showed a steel-gray color. In Nature, for July 3, 1902, W. J. S. Lockyer refers to th6 On Frlday afternoon, April 11. about 4 o'clock. very black clouds gathered in the southwest, and passed on eastward, but there wm only afterglows observed at the Solar Physics Observatory, SoutE a very slight sprinkle of rain. The next morning, Saturday, the air was Kensington, London, England, on June 23, 26, 27, 28, and 29 fllled with what seemed like smoke: but Gonsideriog the great rains we had and at Bombay. India, on about the same dates. liad all the week we were certain the woods were not on flre. The air These are by no means all the reports of the afterglows thal got thickest about 12 or 1 o'clock, when it resumed its normal clearness. -

NJDARM: Collection Guide

NJDARM: Collection Guide - NEW JERSEY STATE ARCHIVES COLLECTION GUIDE Record Group: Governor Franklin Murphy (1846-1920; served 1902-1905) Series: Correspondence, 1902-1905 Accession #: 1989.009, Unknown Series #: S3400001 Guide Date: 1987 (JK) Volume: 6 c.f. [12 boxes] Box 1 | Box 2 | Box 3 | Box 4 | Box 5 | Box 6 | Box 7 | Box 8 | Box 9 | Box 10 | Box 11 | Box 12 Contents Explanatory Note: All correspondence is either to or from the Governor's office unless otherwise stated. Box 1 1. Elections, 1901-1903. 2. Primary election reform, 1902-1903. 3. Requests for interviews, 1902-1904 (2 files). 4. Taxation, 1902-1904. 5. Miscellaneous bills before State Legislature and U.S. Congress, 1902 (2 files). 6. Letters of congratulation, 1902. 7. Acknowledgements to letters recommending government appointees, 1902. 8. Fish and game, 1902-1904 (3 files). 9. Tuberculosis Sanatorium Commission, 1902-1904. 10. Invitations to various functions, April - July 1904. 11. Requests for Governor's autograph and photograph, 1902-1904. 12. Princeton Battle Monument, 1902-1904. 13. Forestry, 1901-1905. 14. Estate of Imlay Clark(e), 1902. 15. Correspondence re: railroad passes & telegraph stamps, 1902-1903. 16. Delinquent Corporations, 1901-1905 (2 files). 17. Robert H. McCarter, Attorney General, 1903-1904. 18. New Jersey Reformatories, 1902-1904 (6 files). Box 2 19. Reappointment of Minister Powell to Haiti, 1901-1902. 20. Corporations and charters, 1902-1904. 21. Miscellaneous complaint letters, December 1901-1902. file:///M|/highpoint/webdocs/state/darm/darm2011/guides/guides%20for%20pdf/s3400001.html[5/16/2011 9:33:48 AM] NJDARM: Collection Guide - 22. Joshua E. -

An Index to the Bulletin of Atlanta University

AN INDEX TO THE BULLETIN OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY, 1901 THROUGH DECEMBER, 1903 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN LIBRARY SERVICE BY RUTH LeFLORE WARD SCHOOL OF LIBRARY SERVICE ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 1963 4, J 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 Purpose and Scope Methodology II. INDEX S BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 ii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION An index, as defined in the American Library Association's Glossary of Terms, is "a list of topics, names, et cetera, treated in a book or a group of books, with references to pages where they occur." Robert Collison said: The indexing of periodicals is based on the same principles as those for the indexing of books, but it involves a stricter discipline, a wider knowledge of unswerving consistency. ...An index to perioci- cals is however an operation carried out over a long period ... and it covers a greater amount and variety of material, generally speaking. Continuative indexing means that the principles on which the index is compiled in one month must be strictly followed in all further installments if the reader is to discover quickly and easily all the material on his subject.2 At the time of the first publication of the Bulletin of Atlanta 3 University in June, 1883, the University itself had been in existence for fourteen years. The Bulletin was a link which provided reports on the progress of the University as well as progress of the South in general. -

TV on the Afrikaans Cinematic Film Industry, C.1976-C.1986

Competing Audio-visual Industries: A business history of the influence of SABC- TV on the Afrikaans cinematic film industry, c.1976-c.1986 by Coenraad Johannes Coetzee Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art and Sciences (History) in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Anton Ehlers December 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za THESIS DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS Historical research frequently requires investigations that have ethical dimensions. Although not to the same extent as in medical experimentation, for example, the social sciences do entail addressing ethical considerations. This research is conducted at the University of Stellenbosch and, as such, must be managed according to the institution’s Framework Policy for the Assurance and Promotion of Ethically Accountable Research at Stellenbosch University. The policy stipulates that all accumulated data must be used for academic purposes exclusively. This study relies on social sources and ensures that the university’s policy on the values and principles of non-maleficence, scientific validity and integrity is followed. All participating oral sources were informed on the objectives of the study, the nature of the interviews (such as the use of a tape recorder) and the relevance of their involvement. -

Apartheid Legislation in South Africa

Ralph Glücksmann Apartheid Legislation in South Africa I. Introduction On 31 May 1910 the Union of South Africa was formed as a dominion in the British Empire. It was exactly eight years after the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging, which had brought the Second Anglo-Boer War to an end and stipulated full British sovereignty over the Boer republics of Transvaal and Orange Free State. Although the South Africa Act 1909 (9 Edw. VII c. 9) was passed by the British Parliament at Westminster, it was wholly constructed by South African representatives in South Africa. Agreement had not been reached without acrimony, and there were times when it seemed that the national convention of representatives of the four colonies Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange River might break up among recriminations. Das Kap wurde 1806 britische Kolonie. Davor war das Kap eine niederländische Kolonie, gegründet von der Niederländischen Ostindien-Kompanie (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), die vom niederländischen Staat Hoheitsrechte erhalten hatte. Als die Niederlande 1795 im Zuge des ersten Koalitionskrieges von Frankreich be- setzt wurden, nutzten die Briten eine Rebellion in der Kapkolonie, um diese unter ihre Herrschaft zu bringen und den Franzosen zuvorzukommen. 1803 zogen sich die Briten nach dem Frieden von Amiens zunächst wieder zu- rück und überließen das Kap der Batavischen Republik als Rechtsnachfolgerin der 1798 aufgelösten Niederlän- dischen Ostindien-Kompanie. Bereits 1806 annektierte Großbritannien nach der Schlacht von Blauberg die Kap- kolonie jedoch endgültig, nachdem die napoleonischen Kriege in Europa wieder aufgeflammt waren. 1815 wur- de die Abtretung an das britische Kolonialreich auf dem Wiener Kongress von den Niederlanden bestätigt, die als Kompensation die früheren Österreichischen Niederlande erhielten. -

The Politics of History in South Africa

The Politics of History in South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1978_11 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Politics of History in South Africa Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 11/78 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; Magubane, Bernard Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1978-07-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1500-1960 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Introduction. The nature of society. African societies in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The white settlers. -

Dynamics and Impacts of the May 8Th, 1902 Pyroclastic Current at Mount Pelée (Martinique): New Insights from Numerical Modeling

University of South Florida Scholar Commons School of Geosciences Faculty and Staff Publications School of Geosciences 7-2020 Dynamics and Impacts of the May 8th, 1902 Pyroclastic Current at Mount Pelée (Martinique): New Insights From Numerical Modeling Valentin Gueugneau University of South Florida, [email protected] Karim Kelfoun Université Clermont Auvergne Sylvain J. Charbonnier University of South Florida, [email protected] Aurelie Germa University of South Florida, [email protected] Guillaume Carazzo Université de Paris Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/geo_facpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Scholar Commons Citation Gueugneau, Valentin; Kelfoun, Karim; Charbonnier, Sylvain J.; Germa, Aurelie; and Carazzo, Guillaume, "Dynamics and Impacts of the May 8th, 1902 Pyroclastic Current at Mount Pelée (Martinique): New Insights From Numerical Modeling" (2020). School of Geosciences Faculty and Staff Publications. 2256. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/geo_facpub/2256 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Geosciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Geosciences Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. feart-08-00279 July 20, 2020 Time: 12:14 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 22 July 2020 doi: 10.3389/feart.2020.00279 Dynamics and Impacts of the May 8th, 1902 Pyroclastic Current at Mount Pelée (Martinique): New Insights From Numerical Modeling -

Rewriting Empire: the South African War, the English Popular Press, and Edwardian Imperial Reform

Rewriting Empire: The South African War, The English Popular Press, and Edwardian Imperial Reform Lauren Young Marshall Charlottesville, Virginia B.A. Longwood University, 2004 M.A. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Department of History University of Virginia August, 2017 ________________________________ Dr. Stephen Schuker ________________________________ Dr. Erik Linstrum ________________________________ Dr. William Hitchcock ________________________________ Dr. Bruce Williams Copyright © 2017 Lauren Y Marshall Table of Contents ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS v INTRODUCTION 1 Historiographical Survey 12 CHAPTER ONE 33 The Press, The Newspapers, and The Correspondents The Pre-War Imperial Context 33 The Rise of The Popular Press 48 The Newspapers, The Correspondents, and Their 52 Motivations CHAPTER TWO 79 The Siege of Mafeking, Army Blunders, and Post-War Military Reform Early Mistakes 79 The Sieges: Mafeking and Its Aftermath 108 The Khaki Election of 1900 152 Post-War Military Reforms 159 CHAPTER THREE 198 Domestic Anti-War Activity, Pro-Boers, and Post-War Social Reform Anti-War Organizations and Demonstrations 198 The Concentration Camps, The Backlash, and Censorship 211 Post-War Social Reforms 227 CHAPTER FOUR 245 The Treaty of Vereeniging, The Fallout, Chamberlain, and Post-War Economic Reform The War’s Conclusion, Treaty Negotiations, and Reactions 245 Post-War Economic Reforms 255 South Africa as a Microcosm of Federation and The 283 Shifting Boer Myth CONCLUSION 290 The War’s Changing Legacy and The Power of the Press BIBLIOGRAPHY 302 i Abstract This dissertation explores the ways in which English newspaper correspondents during the South African War utilized their commentaries and dispatches from the front to expose British imperial weaknesses. -

High Winds at Point Reyes Light, Cal

MAY, 1903. MONTHLY WEA!CHER REVIEW. 227 leaving a trail like a narrow cloud for Borne length of time. the extreme hourly velocities are deduced from the records Thunder at Pepeekeo, May 1. Snow on Mauna Loa 21st. for single miles. The table referred to by Professor McAdie Heavy surf 15-19, 23-28. will be found on page 220.-C. A. The rainfall of 1902 was extraordinary in amount in all dis- tricts, Naalehu and Hilea in Kau and Waiawa in Kauai being LANTERN SLIDES. the only exceptional stations, while at some points the rainfall Dr. 0. L. Fassig communicates the following list of lantern was more than twice the normal. slides that he haR had made for his lectures on meteorology at Figures in black type indicate that one or two months are Baltimore, Md. Duplicates of the slides marked “ n ” (nega- missing from the gear’s record, but are interpolated from ad- tives) can be furnished those who desire them at the rate of 25 jacent stations. Where three or inore months are lacking cents each; a negative and slide will cost 50 cents. If any item the station is omitted from this list. includes many slides the corresponding number is given. Mema temperatwe table for May, 1303. 1. Whirling alto-stratus. 1 11. Umbrella cloud. MONTHLYWEATHER REVIEW. 1902. 1 n. Diurnal barometric wave, North America and South America. Stations. 111. Diurnal Iiaronietric wave, path of center. 1. Solar halo, Columbus, Ohio. - ~~~~ .__ ~__ 1n. C,luster of snow crystals. 0 0 RrI. O 2. The ‘I tTJllbria ” after a snowstorm. -

Football in Europe.Pdf

University of Pristina, Faculty of FIEP Europe – History of Sport and Physical Education in Physical Education and Sport Leposaviæ Section Book: FOOTBALL IN EUROPE Editors: Petar D. Pavlovic (Republic of Srpska) Nenad Zivanovic (Serbia) Branislav Antala (Slovakia) Kristina M. Pantelic Babic, (Republic of Srpska) Publishers: University of Pristina, Faculty of Sport and Physical Education in Leposavic FIEP Europe - History of Physical Education and Sport Section For publishers: Veroljub Stankovic Nenad Zivanovic 2 Reviewers: Branislav Antala (Slovakia) Nenad Zivanovic (Serbia) Sladjana Mijatovic (Serbia) Nicolae Ochiana (Romania) Veroljub Stankovic (Serbia) Violeta Siljak (Serbia) Prepress: Kristina M. Pantelic Babic Book-jacket: Anton Lednicky Circulation: Printed by: ISBN NOTE: No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior permission of the authors. 3 Authors: Balint Gheorghe (Romania) Dejan Milenkovic (Serbia) Elizaveta Alekseevna Bogacheva (Russia) Emeljanovas Arūnas (Lithuania) Fedor Ivanovich Sobyanin (Russia) Ferman Konukman (Turkey) Giyasettin Demirhan (Turkey) Igor Alekseevich Ruckoy (Russia) Javier Arranz Albó (Spain) Kristina M. Pantelic Babic (Republic of Srpska) Majauskienė Daiva (Lithuania) Petar D. Pavlovic (Republic of Srpska) Sergii Ivashchenko (Ukraine) Zamfir George Marius (Romania) 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ............................................................................................. 6 FROM THE RISE OF FOOTBALL IN LITHUANIA TO THE PARTICIPATION OF THE LITHUANIAN FOOTBALL SELECTION -

South African Republic 1 South African Republic

South African Republic 1 South African Republic For other uses, see South Africa (disambiguation). South African Republic Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek ← 1856–1902 → ← Flag Coat of arms Anthem Transvaalse Volkslied Location of the South African Republic, circa 1890. [1] Capital Pretoria 25°43′S 28°14′E Languages Dutch Religion Nederduitsch Hervormde Kerk Government Republic President - 1857–1863 Marthinus Wessel Pretorius - 1883–1902 Paul Kruger - 1900–1902 Schalk Willem Burger (acting) History - Established 27 June 1856 - British annexation 1877–1881 - Second Boer War 11 October 1899 South African Republic 2 - Treaty of Vereeniging 31 May 1902 Area - 1870 191,789 km² (74,050 sq mi) Population - 1870 est. 120,000 Density 0.6 /km² (1.6 /sq mi) Currency South African Republic pond Today part of South Africa The South African Republic (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek or ZAR), was an independent and Internationally recognized Dutch Language country in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century (Recognised by the USA, United Kingdom, Germany and others). The ZAR was established in 1852, and was independent from 1856 to 1902. The country was attacked by the United Kingdom in 1881, this is often referred to as the First Boer War. The country defeated the British and remained an independent country until the end of the Second Boer War, on 31 May 1902 when it was forced to surrender to the British. It occupied an area around the present South African province of Gauteng. Names of the country Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) The burghers (citizens) called the Dutch Language country the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (South African Republic or the ZAR) and in all country documentation, the name of the country was either the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek or The South African Republic. -

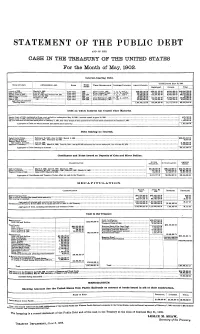

Statement of the Public Debt

STATEMENT OF THE PUBLIC DEBT AND OF THE CASH DST THE TREASURY OP THE UNITED STATES Por the Month of May, 1902. luterest-bearing Debt. OUTSTANDING MAY 31,1902. TITLE OF LOAN. AUTHORIZING ACT. WHEN WHEN REDEEMABLE. INTEREST PAYABLE. AMOUNT ISSUED. ISSUED. Registered. Coupon. Total. Consols of 1930 March 14,1900 2 per cent.. 1900. After April 1,1930.... J., O., J., and A.. $446,940,750 00 $436,251,700 00 $9,689,060 00 $446,940,760 00 Loan of 190S-1918 s ' June 13,1898 8 per cent.. After August 1,1908.. A.,N., F.,andM., 198,792,660 00 60,208,340 00 47,307,320 00 97,516,660 00 1877-1879. Funded Loan of 1907 | July 14,1870, and January 20,1871. 4 per cent.. After July 1,1907 J., A., J., and O.. 740,923,550 00 182,647,950 00 50,629,460 00 233,177,400 00 Refunding Certificates ! February 26,1879 4 per cent.. 1879 do After February 1,1926. 104,003,950 00 30,990,260 00 31,980 00 Loan of 1925 ; January 14,18W 4 per cent.. 1895-1896. F., M., A., andN., 40,012,760 00 1894-1895. After February 1,1904. 10,854,650 00 8,555,700 00 134,994,200 00 Loan of 1904 ! do 5 per cent.. do 162,315,400 00 Aggregate of Interest- j 1,687,985,11100,000,000 00 783,866,590 00 147,171,770 00 931,070,3419,410,360 00 Bearing Debt j Debt on which Interest has Ceased since Maturity.