Peregrine Falcon Falco Peregrinus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Erin Species at Risk Chimney Swift

Tow n of Erin Species at Habitat: Before European settlement of What can you do ? If possible, keep your North America, chimney swifts nested old brick chimney; don’t have your Risk – Chimney Swift primarily in large hollow trees. chimney cleaned in nesting season (mid- However with the decline of old forest May to mid-August). If possible keep habitats over much of their range, your chimney free of obstructions and swifts showed their adaptability and avoid the use grills or caps. Keep any old became urban creatures – relying on trees with hollow trunks on your property chimneys as nesting habitat. Chimney if it is safe to do so. Eliminate or reduce swift flocks can be heard making high- your use of insecticides to an absolute pitched chipping or twittering noises as minimum. they fly above the rooftops older neighbourhoods in Erin during the Bird Studies Canada (BSC) is a non- summer. government organization dedicated to Threats: Several factors have conserving wild birds of Canada. One of combined to cause swift populations BSC’s citizen science projects is the Chimney swifts are often described as to plummet more than 90% in the monitoring of chimney swifts and other ‘cigars with wings’. Their twittering last three decades. Throughout aerial insectivores through its ‘Swift calls give them away as they fly over North America there has been a Watch’ Program. Volunteers conduct older parts of cities and towns. wide-spread decline in insect surveys of swifts and gather information populations, likely caused by to help understand how swifts are faring Description: Chimney swifts look a changing agricultural practices and and what is behind their population bit like swallows, but their swept- widespread use of insecticides; declines . -

How to Be a Good Chimney Swift Landlord

NATURE LONDON HOW TO BE A GOOD CHIMNEY SWIFT CHIMNEY LANDLORD SWIFT Winifred Wake INITIATIVE Chimney Swift Liaison for Nature London Updated April 1, 2021 TIPS FOR HOSTING CHIMNEY SWIFTS: QUICK SUMMARY (details start page 3) If there are swifts in your chimney, consider yourself not only lucky but honored! You have the rare privilege of hosting a species at risk and seeing its life story un- fold right on your own premises. Here are some tips for being a good swift host: • Clean your chimney every year (best done in early April before swifts return). • Don’t use your furnace or fireplace during the season swifts are present. • Keep the damper of your fireplace closed during swift season. • Do not cap the chimney or line it with metal; if considering a conversion to gas, vent elsewhere. • If a metal lining is installed, cap the chimney to prevent swifts and other wildlife from being trapped inside. • Make chimney and roof repairs when swifts are out of the country (mid-October to mid-April). • To keep nuisance animals out of the chimney, trim back overhanging foliage and securely wrap a 60-cm- wide band of metal flashing around the outside of the chimney near the top. • If pruning trees, leave some dead branches with fine twigs at the tips for swifts to use as nesting material. • If you are bothered by food-begging calls in the two weeks before young swifts leave the chimney, stuff foam rubber (not fiberglass insulation) above the damper in your fireplace; be sure to remove it later. -

How to Be a Good Chimney Swift Landlord

HOW TO BE A GOOD CHIMNEY SWIFT LANDLORD Winifred Wake Chimney Swift Liaison for Nature London March 12, 2019 TIPS FOR HOSTING CHIMNEY SWIFTS: QUICK SUMMARY If there are swifts in your chimney, consider yourself not only lucky but honored! You have the rare privilege of hosting a species at risk and seeing its life story un- fold right in your own yard. Here are some tips on how to be a good swift host: Clean your chimney every year (best done in early April before swifts return). Don’t use your furnace or fireplace during the season swifts are present. Keep the damper of your fireplace closed during swift season. Do not cap the chimney or line it with metal; if considering a conversion to gas, vent elsewhere. If a metal lining is installed, cap the chimney to prevent swifts and other wildlife from being trapped inside. Make chimney and roof repairs when swifts are out of the country. To keep nuisance animals out of the chimney, trim back overhanging foliage and securely wrap a 60-cm- wide band of metal flashing around the outside of the chimney near the top. If pruning trees, leave some dead branches with fine twigs at the tips for swifts to use as nesting material. If you are bothered by noisy food-begging calls in the two weeks before young swifts leave the chimney, stuff foam rubber (not fiberglass insulation) above the damper in your fireplace; be sure to remove it later. Welcome swifts to your chimney – they eat huge numbers of flying insects, make minimal mess, do no structural damage to the chimney, and pose no fire or health hazard. -

CR08011 Bird Brochure

Your Guide to Birding at CHIMNEY ROCK WELCOME LEGEND TO BIRD LIST Chimney Rock at Chimney Rock State Park, located in Hickory Nut SEASONS Gorge, offers excellent opportuni- Spring - March, April, May ties for bird watching throughout Summer - June, July, August the seasons due to its endless Fall - September, October, November variety of habitats ranging from Winter - December, January, February riverbanks to high cliffs. Along the Rocky Broad River, ABUNDANCE floodplain trees and wet thickets C –Common and widespread, easily seen throughout attract Yellow and Yellow-throated the Park Warblers. Belted Kingfishers may be seen sitting on a branch surveying the river. Climbing up the north-facing slopes, the vegetation changes. Moist cove forests U–Uncommon, smaller numbers present, seen in alternate with drier oak-mixed hardwoods forests. Rhododendrons are very common appropriate habitat in these woods. A mixed oak forest with hickories and dogwoods covers the east side R– Rare, occurs annually in small numbers of the mountain. These deciduous forests attract many summer-breeding birds. A– Accidental, one or two records for the Park Scarlet Tanagers are common, and up to 15 warblers and vireos can be found here * – Breeding confirmed during the summer months. The most elusive of these are the Cerulean and Swainson’s Warblers. Cerulean Warblers prefer the tall trees immediately below the parking lot at the Chimney, and the Swainson’s Warbler is found in rhododendron HABITAT PREFERENCE This outline serves as a guide to the main habitats in the thickets, especially along the Hickory Nut Falls Trail. Park and as a key to the areas where the birds are most The high cliffs on top of the steep, north-facing wooded slopes have an unusually likely to be seen. -

Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures

Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures Photo: R. Kimpel (flickr.com/creative commons) ontario.ca/speciesatrisk BLEED Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry 2017 Suggested Citation Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2017 Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2017. 22 pp. Authors This document was prepared by Debbie Badzinski, Brandon Holden and Sean Spisani of Stantec Consulting Ltd. and Kristyn Richardson of Bird Studies Canada on behalf of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Acknowledgements The project team wishes to acknowledge the following individuals for providing guidance and review of this document: ´ Todd Copeland, Darlene Dove, Lauren Kruschenske, Megan McAndrew, Kerry Reed, Chris Risley, Lara Griffin and Erin Thompson Seabert from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry ´ Larry Sarris from the Ontario Ministry of Transportation ´ Nicole Kopysh from Stantec Consulting Ltd. This document includes best available information as of the date of publication and will be updated as new information becomes available. If you are interested in providing information for consideration in updates of this document, please email [email protected]. Page 1 | Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures 1.0 Introduction & Purpose ..........................................................................................3 -

Airbirds: Adaptative Strategies to the Aerial Lifestyle from a Life History Perspective

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 Airbirds: Adaptative Strategies to the Aerial Lifestyle From a Life History Perspective. Manuel Marin-aspillaga Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Marin-aspillaga, Manuel, "Airbirds: Adaptative Strategies to the Aerial Lifestyle From a Life History Perspective." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6849. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6849 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Chimney Swift Nest Site Research Project As a Research Associate!

Driftwood Wildlife Association P.O. Box 300369 Austin, Texas 78703 WHAT IN THE WORLD IS THAT SOUND ? Chimney Swifts create a variety of sounds during their stay with us in North America during the warmer months. There is the "whooshing" sound of their wings as they come and go from the chimney. They utter a gentle "chippering" as they socialize with one another in the roost during nest-building and at night. The most audible sounds are those of the young which have two basic Chimney Swifts historically vocalizations: the feeding call which is a very loud, high-pitched nested and roosted in hollow trees. "yippering" as they beg for food from the returning parents, and their As American pioneers moved mechanical, hissing alarm call which they make when disturbed or westward across the continent, they frightened. cleared forests and removed the As long as the young are making the loud feeding call, they are swifts' natural habitat. The birds incapable of sustained flight and are completely dependent on their that Audubon called American parents for food. Homeowners' tolerance during this critical period Swifts became known as Chimney of the swifts' development is very important. If the young are forced Swifts as they readily adapted to the from the chimney during this period, they will perish -- slowly starve masonry chimneys erected by those to death over a period of several days. The parents are unable to care same pioneers. Over the decades, for them outside of their chimney. the range of the swifts expanded and Once the sound of the young becomes noticeable, they are usually their numbers swelled with the ever only 10 days or so from fledging. -

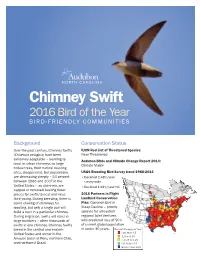

Chimney Swift 2016 Bird of the Year BIRD-FRIENDLY COMMUNITIES

Chimney Swift 2016 Bird of the Year BIRD-FRIENDLY COMMUNITIES Background Conservation Status Over the past century, Chimney Swifts IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: (Chaetura pelagica) have been Near Threatened extremely adaptable – learning to Audubon Birds and Climate Change Report 2014: roost in urban chimneys as large Climate Stable hollow trees, their natural roosting sites, disappeared. But populations USGS Breeding Bird Survey trend 1966-2013 are decreasing steeply – 53 percent •Declined 2.48%/year between 1966 and 2007 in the survey-wide United States – as chimneys are •Declined 1.61%/year NC capped or removed, leaving fewer places for swifts to nest and raise 2016 Partners in Flight their young. During breeding, there is Landbird Conservation some sharing of chimneys for Plan: Common Bird in roosting, but only a single pair will Steep Decline – priority build a nest in a particular chimney. species for all eastern During migration, swifts will roost in regional Joint Ventures large numbers – often thousands of with predicted loss of 50% swifts in one chimney. Chimney Swifts of current global population breed in the central and eastern in under 30 years. Percent Change per Year United States and winter in the Less than 1.5 -1.5 to -0.25 Amazon basin of Peru, northern Chile, > -0.25 to 0.25 and northwest Brazil. > 0.25 to +1.5 Greater than +1.5 Four Ways You Can Help 1 Keep Your Chimney Open The practice of capping older chimneys makes 2 them inaccessible to swifts. One solution is to Be a Citizen hire a chimney sweep to Scientist cap the chimney in Report nesting and 3 November and open it up roosting sites at again before Chimney Construct A nc.audubon.org. -

Birds in My Neighborhood®

Birds in my Neighborhood® This journal belongs to: __________________________________________ Birds in my Neighborhood® is a partnership between Openlands and Audubon-Great Lakes, funded through the US Forest Service-International Programs. 2 Birds in my Neighborhood® Journal Table of Contents $FWLYLWLHVWRFRPSOHWHEHIRUHVFKRRO\DUGZDON««««««««««-8 %LUGZDONFKHFNOLVW««««««««««««««««««««««««-10 6FKRRO\DUGZDONUHVXOWV««««««««««««««««««««««« $FWLYLWLHVWRFRPSOHWHEHIRUHILHOGWULS««««««««««««««« )LHOGWULSZDONUHVXOWV«««««««««««««««««««««««-14 0RUHDERXWELUGV«««««««««««««««««««««««-19 3 Before Schoolyard Walk What I already know about birds 4 Birds in my Neighborhood® Journal Before Schoolyard Walk Birds I already know 5 Before Schoolyard Walk What I want to know about birds 6 Birds in my Neighborhood® Journal Before Schoolyard Walk Discovering the birds in my neighborhood Choose a bird species from the bird checklist, and find out as much as you can about that bird. Write what you learned, in your own words. 7 Before Schoolyard Walk Drawings of the bird I studied 8 Birds in my Neighborhood® Journal Bird Walk Checklist Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip Northern Cardinal Common Grackle Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip American Robin Mallard Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip Blue Jay Canada Goose Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip Chimney Swift House Sparrow Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip American Goldfinch Barn Swallow 9 Bird Walk Checklist Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip Red-winged Blackbird European Starling Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip Rock Dove American Crow Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip Mourning Dove Downy Woodpecker Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip Gull Black-capped Chickadee Neighborhood Neighborhood Field trip Field trip ______________ ______________ 10 Birds in my Neighborhood® Journal Schoolyard Walk Results Fill in the bar graph below to show how many birds of each species you saw on your walk. -

Unusual Behavior in the Chimney Swift.-Birds, As Well As Many Other Animals, Have Been Observed to Behave Very Differently in Large Groups Than When Alone

December,1939 Vol. 51, No. 4 GENERAL NOTES 243 ten birds were observed but were generally inactive. The morning was calm, clear and warm and early enough in the season for a more active booming display. Reports have been received of a resident flock of Prairie Chickens 4 miles north and 1 mile west of LeRoy, Minnesota. These birds were reported booming in this area in the spring of 1939. Another resident flock has been reported in an un- drained area 2 miles south and 1 mile east of Grand Meadow, Minnesota. Although several visits were made to the areas by the writer, the reports have not been verified by actual observations. Analysis of available information indicate that the Prairie Chicken in south- eastern Minnesota is slowly declining in numbers and that their existence is largely dependent on the maintenance of large undisturbed breeding grounds in the undrained prairie lands. It is doubtful whether the Prairie Chicken have even maintained their populations during the past three years. A shift in farming from cultivated crops to grass crops may retard this decline. General observations on these Prairie Chicken while booming, flushing or cruis- ing indicate the birds are unusually timid, probably the result of direct disturbance or the harmful changes in their environment by man. The flushing distance was usually more than 100 yards and the flight limit beyond the human vision- URBAN C. NELSON, Soil Conservation Service, Chillicothe, Missouri. Food of the Short-eared Owl During Migration Through Pennsylvania.- Since July 1, 1938, the food habits of all raptors on the 1,675acre Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus torquatus) study area in Lower Macungie Town- ship, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, have been investigated by the Pennsylvania Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit for the purpose of determining the effects of birds of prey upon the pheasant population. -

Bird Species List

PIGEONS AND Common Tern WOODPECKERS DOVES Forster’s Tern Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Faville Grove Sanctuary’s Rock Pigeon Red-headed Woodpecker Mourning Dove LOONS Red-bellied Woodpecker BIRD SPECIES LIST Common Loon Downy Woodpecker CUCKOOS Hairy Woodpecker Updated April 2020 Yellow-billed Cuckoo CORMORANTS Black-billed Cuckoo Double-crested Cormorant Pileated Woodpecker Protecting, supporting, and enjoying birds are what make our Northern Flicker organization sing! Madison Audubon’s Faville Grove Sanctuary NIGHTJARS PELICANS American White Pelican FALCONS was established in 1998 with the goal of conserving and reestab- Common Nighthawk Eastern Whip-poor-will American Kestrel lishing native habitats for the benefit of birds, mammals, plants, Merlin insects, and people. The wide range of habitats that you find at SWIFTS HERONS, IBIS, AND Faville Grove are a result of fascinating and diverse geology, burn Chimney Swift ALLIES FLYCATCHERS history, and microclimates. This 171-species bird list was pulled American Bittern Eastern Wood-Pewee from eBird on April 22, 2020. HUMMINGBIRDS Great Blue Heron Willow Flycatcher Ruby-throated Hummingbird Great Egret Least Flycatcher Eastern Phoebe You’re invited to explore the sanctuary. How many species will Green Heron Great Crested Flycatcher you find? RAILS THROUGH CRANES VULTURES, HAWKS, AND Eastern Kingbird Alder/Willow Flycatcher Virginia Rail ALLIES (Traill’s) madisonaudubon.org/faville-grove Sora Turkey Vulture Olive-sided Flycatcher American Coot Osprey Alder Flycatcher Sandhill Crane Northern -

Birds on Canal Shores

May 21, 2020 Birds Seen from Canal Shores Golf Course (180 species) Waterfowl American White Pelican Snow Goose Canada Goose Trumpeter Swan Wood Duck Blue-winged Teal American Wigeon Mallard Northern Pintail Redhead Ring-necked Duck Greater Scaup Lesser Scaup Bufflehead Common Goldeneye Hooded Merganser Common Merganser Red-Breasted Merganser Ruddy Duck Grebes Pied-billed Grebe Horned Grebe Pigeons and Doves Rock Pigeon Mourning Dove Cuckoos Yellow-billed Cuckoo Black-billed Cuckoo Nightjars Common Nightjar Eastern Whip-poor-will 1 Swifts Chimney Swift Hummingbirds Ruby-throated Hummingbird Rails and Allies Sora American Coot Cranes Sandhill Cranes Shorebirds Kildeer American Woodcock Wilson’s Snipe Spotted Sandpiper Solitary Sandpiper Gulls and Terns Bonaparte’s Gull Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Caspian Tern Loons Common Loon Cormorants Double-crested Cormorant Herons and Allies Great Blue Heron Great Egret Green Heron Black-crowned Night Heron 2 Vultures, Hawks, and Allies Turkey Vulture Osprey Sharp-shimmed Hawk Cooper’s Hawk Red-shouldered Hawk Broad-winged Hawk Red-tailed Hawk Owls Barn Owl Eastern Screech Owl Great Horned Owl Short-eared Owl Long-eared Owl Northern Saw-whet Owl Kingfishers Belted Kingfisher Woodpeckers Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Red-headed Woodpecker Red-bellied Woodpecker Downy Woodpecker Hairy Woodpecker Northern Flicker Falcons American Kestrel Merlin Peregrine Falcon Flycatchers, Pewees, Kingbirds, and Allies Olive-sided Flycatcher Eastern Wood-Pewee Yellow-bellied Flycatcher Acadian Flycatcher 3 Alder Flycatcher