Blomefield Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Share Report

PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS For period ended 30th September 2019 SUMMARY OF PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS BY DEANERIES Dean Amount % Deanery Share Received for 2019 % Deanery Share % No Outstanding 2018 2019 to period end 2018 Received for 2018 received £ £ £ £ £ Norwich Archdeaconry 06 Norwich East 23,500 4.41 557,186 354,184 63.57 532,380 322,654 60.61 04 Norwich North 47,317 9.36 508,577 333,671 65.61 505,697 335,854 66.41 05 Norwich South 28,950 7.21 409,212 267,621 65.40 401,270 276,984 69.03 Norfolk Archdeaconry 01 Blofield 37,303 11.04 327,284 212,276 64.86 338,033 227,711 67.36 11 Depwade 46,736 16.20 280,831 137,847 49.09 288,484 155,218 53.80 02 Great Yarmouth 44,786 9.37 467,972 283,804 60.65 478,063 278,114 58.18 13 Humbleyard 47,747 11.00 437,949 192,301 43.91 433,952 205,085 47.26 14 Loddon 62,404 19.34 335,571 165,520 49.32 322,731 174,229 53.99 15 Lothingland 21,237 3.90 562,194 381,997 67.95 545,102 401,890 73.73 16 Redenhall 55,930 17.17 339,813 183,032 53.86 325,740 187,989 57.71 09 St Benet 36,663 9.24 380,642 229,484 60.29 396,955 243,433 61.33 17 Thetford & Rockland 31,271 10.39 314,266 182,806 58.17 300,933 192,966 64.12 Lynn Archdeaconry 18 Breckland 45,799 11.97 397,811 233,505 58.70 382,462 239,714 62.68 20 Burnham & Walsingham 63,028 15.65 396,393 241,163 60.84 402,850 256,123 63.58 12 Dereham in Mitford 43,605 12.03 353,955 223,631 63.18 362,376 208,125 57.43 21 Heacham & Rising 24,243 6.74 377,375 245,242 64.99 359,790 242,156 67.30 22 Holt 28,275 8.55 327,646 207,089 63.21 330,766 214,952 64.99 23 Lynn 10,805 3.30 330,152 196,022 59.37 326,964 187,510 57.35 07 Repps 0 0.00 383,729 278,123 72.48 382,728 285,790 74.67 03 08 Ingworth & Sparham 27,983 6.66 425,260 239,965 56.43 420,215 258,960 61.63 727,583 9.28 7,913,818 4,789,282 60.52 7,837,491 4,895,456 62.46 01/10/2019 NORWICH DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE LTD DEANERY HISTORY REPORT MONTH September YEAR 2019 SUMMARY PARISH 2017 OUTST. -

Council Tax Rates 2020 - 2021

BRECKLAND COUNCIL NOTICE OF SETTING OF COUNCIL TAX Notice is hereby given that on the twenty seventh day of February 2020 Breckland Council, in accordance with Section 30 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992, approved and duly set for the financial year beginning 1st April 2020 and ending on 31st March 2021 the amounts as set out below as the amount of Council Tax for each category of dwelling in the parts of its area listed below. The amounts below for each parish will be the Council Tax payable for the forthcoming year. COUNCIL TAX RATES 2020 - 2021 A B C D E F G H A B C D E F G H NORFOLK COUNTY 944.34 1101.73 1259.12 1416.51 1731.29 2046.07 2360.85 2833.02 KENNINGHALL 1194.35 1393.40 1592.46 1791.52 2189.63 2587.75 2985.86 3583.04 NORFOLK POLICE & LEXHAM 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 175.38 204.61 233.84 263.07 321.53 379.99 438.45 526.14 CRIME COMMISSIONER BRECKLAND 62.52 72.94 83.36 93.78 114.62 135.46 156.30 187.56 LITCHAM 1214.50 1416.91 1619.33 1821.75 2226.58 2631.41 3036.25 3643.49 LONGHAM 1229.13 1433.99 1638.84 1843.70 2253.41 2663.12 3072.83 3687.40 ASHILL 1212.28 1414.33 1616.37 1818.42 2222.51 2626.61 3030.70 3636.84 LOPHAM NORTH 1192.57 1391.33 1590.09 1788.85 2186.37 2583.90 2981.42 3577.70 ATTLEBOROUGH 1284.23 1498.27 1712.31 1926.35 2354.42 2782.50 3210.58 3852.69 LOPHAM SOUTH 1197.11 1396.63 1596.15 1795.67 2194.71 2593.74 2992.78 3591.34 BANHAM 1204.41 1405.14 1605.87 1806.61 2208.08 2609.55 3011.01 3613.22 LYNFORD 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 -

Marriott's Way Walking and Cycling Guide

Marriott’s Way Walking and Cycling Guide 1 Introduction The routes in this guide are designed to make the most of the natural Equipment beauty and cultural heritage of Marriott’s Way, which follows two disused Even in dry weather, a good pair of walking boots or shoes is essential for train lines between the medieval city of Norwich and the historic market the longer routes. Some of Marriott’s Way can be muddy so in some areas a town of Aylsham. Funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, they are a great way road bike may not be suitable and appropriate footwear is advised. Norfolk’s to delve deeper into this historically and naturally rich area. A wonderful climate is drier than much of the county but unfortunately we can’t array of habitats await, many of which are protected areas, home to rare guarantee sunshine, so packing a waterproof is always a good idea. If you are wildlife. The railway heritage is not the only history you will come across, as lucky enough to have the weather on your side, don’t forget sun cream and there are a series of churches and old villages to discover. a hat. With loops from one mile to twelve, there’s a distance for everyone here, whether you’ve never walked in the countryside before or you’re a Other considerations seasoned rambler. The landscape is particularly flat, with gradients being kept The walks and cycle loops described in these pages are well signposted to a minimum from when it was a railway, but this does not stop you feeling on the ground and detailed downloadable maps are available for each at like you’ve had a challenge. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

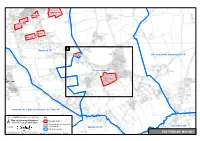

A Frettenham Map

GNLP0190 GNLP0181 GNLP0582 GNLP0512 GNLP0512 A Hainford CP GNLP0065 Horstead with Stanninghall CP Frettenham CP GNLP0492 GNLP0085 Horsham St. Faith and Newton St. Faith CP GREATER NORWICH LOCAL PLAN Key Map set showing Submitted Submitted Sites ± Sites in Frettenham Parish Broads Authority Boundary ( where applicable ) Crostwick CP 1:10,000 Spixworth CP Parish Boundary © Crown Copyright and database right 2016.Ordnance Survey: Broadland District Council - 100022319 Norwich City Council - 100019747 South Norfolk District Council - 100019483 FRETTENHAM MAP SET GP 1.22m RH ED & Ward B dy MILL ROA D 18.6m FB White House Pon ds Pon d Drain Holey well Barn Drain Path (um) Flore nc e Playing Field CH UR C H LA NE Cottage Long Plantation Sta bl e View Cottage Mas ons 15.9m Sta bl e Cottage View Pon d CHURCH ROAD Barn Aca cia Cottage Brac ken Cottage Hall Horstead with Stanninghall CP Grov e Cottage Fa irfi eld 3 Valley Farm Cedar Cottages FRETTENHAM ROAD BUXTON ROAD Pon d The G rang e 1 GP Crown B arn Pon d Rose an d Crown 19.6m 64 (PH ) 50 CR Haw thorn Cottage The Bungalow Rose Cotta ge 2 1 3 48 The Pound Garage Walter 60 Fie ld MILL 11 7 46 Barns FIE LD 40 9 Guide Post COU RT Pon d Mill Fa rm Hainford CP 15.1m 18.1m Lodge Mill View Pon d 54 Grove Farm Drain 1 19.5m Pon d Hainford Place 36 Letter GNLP0065 Box MILL ROA D 34 1 50 The Studio Silos Mill Farm 10 The Willows Pond 42 11 SHIRLEY CLOSE 48 44 6 1.22m RH 6 40 32 Birbeck Way 46 Beulah Cas a M ia Farm 1 16 SCHOOL RO AD Pon d 34 2 27 Thatched Track Cottage Pon d Guide Post RED ME RE CLOSE -

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 Socc Stakeholder Mailing List

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 SoCC Stakeholder Mailing List Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2018 Revision: Version 1 Author: BECG Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Appendices Parish Councils Bacton and Edingthorpe Parish Council Witton and Ridlington Parish Council Brandiston Parish Council Guestwick Parish Council Little Witchingham Parish Council Marsham Parish Council Twyford Parish Council Lexham Parish Council Yaxham Parish Council Whinburgh and Westfield Parish Council Holme Hale Parish Council Bintree Parish Council North Tuddenham Parish Council Colkirk Parish Council Sporle with Palgrave Parish Council Shipdham Parish Council Bradenham Parish Council Paston Parish Council Worstead Parish Council Swanton Abbott Parish Council Alby with Thwaite Parish Council Skeyton Parish Council Melton Constable Parish Council Thurning Parish Council Pudding Norton Parish Council East Ruston Parish Council Hanworth Parish Council Briston Parish Council Kempstone Parish Council Brisley Parish Council Ingworth Parish Council Westwick Parish Council Stibbard Parish Council Themelthorpe Parish Council Burgh and Tuttington Parish Council Blickling Parish Council Oulton Parish Council Wood Dalling Parish Council Salle Parish Council Booton Parish Council Great Witchingham Parish Council Aylsham Town Council Heydon Parish Council Foulsham Parish Council Reepham -

Norfolk. Bishopric. Sonmdn: Yarii'outh Lynn Tmn'rl'oimfl

11 0RF0LK LISTS W 1 Q THE PRESENT TIME; ‘ . n uu lj, of wuum JRTRAITS BLISHED, vE L l s T 0 F ' V INCIAL HALFPENNIES ' - R N ORFOLK LIS TS FROM THE REFORMATION To THE PRESENT TIME ; COMPRIS ING Ll" OP L ORD LIEUTEN ANT BARONET S , S , HIG HERIFF H S S , E B ER O F P A R L IA EN T M M S M , 0 ! THE COUNTY of N ORFOLK ; BIS HOPS DEA S CHA CELLORS ARCHDEAC S , N , N , ON , PREBE DA I N R ES , MEMBERS F PARLIAME T O N , MAYORS SHERIFFS RECORDERS STEWARDS , , , , 0 ? THE CITY OF N ORWIC H ; MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT AND MAYORS 0 ? THE BOROUGHS OP MOUTH LYN N T T R YAR , , HE FO D, AN D C ASTL E RIS IN G f Persons connected with th e Coun Also a List o ty, of whom ENGRAVED PORTRAITS I HAV E B EEN PUBL SHED, A N D A D B S C R I P 'I‘ I V E L I S T O F TRADES MENS ’ TOKIBNS PROV INCIAL HA LFPENNIES ISS UED I” THE Y COUNT OF NORFOLK . + 9 NORWICH ‘ V ' PRINTED BY HATCHB IT, STE ENSON , AN D MATCHB", HARKBT PLACI. I NDEX . Lord Lieutenants ' High Sherifl s Members f or the County Nonw xcH o o o o o o o 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Prebendaries Members f or th e City Ym ou'rn Mayors LYNN Members of Parliament Mayors Membersof Parliament CASTLERISING Members of Parliament Engraved Portraits ’ Tradesmans Tok ens ProvincialHalf pennles County and B orough Members elected in 1 837 L O RD L I EUT EN A N T S NORFOLK) “ ' L r Ratcli e Ea rl of us e h re d Hen y fl n S s x , e si ed at Attle borou h uc eded to th e Ea r d m1 1 g , s ce l o 542 , ch . -

JAMES HORSLEY SR. of MARYLAND (C1685-C1748)

JAMES HORSLEY SR. of MARYLAND (c1685-c1748) AND OUR HORSLEY FAMILY BEGINNINGS Research Report by Joan Horsley © 2006, 2009 Joan Horsley Revised Fall 2010 Contact: [email protected] This document may not be used in part or whole for commercial purposes or paid subscriber services. All personal use must reference the document and author. Cite as: Horsley, Joan. James Horsley Sr. of Maryland (c1685-c1748) and Our Horsley Family Beginnings. Rev. ed. Raleigh, NC: J. Horsley, 2009, Rev. 2010. Available online at: www.JoanHorsley.org 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview – Page 3 Preface - Page 4 PART I: NARRATIVE REPORT – “James Horsley Sr. and Our Horsley Family Beginnings” – Page 6 Early Horsley History in England – Page 6 Horsley in 17 th Century Maryland – Page 7 Richard Horsley as the Possible Father of James Horsley Sr. – Page 16 James Horsley Sr. – The Annapolis Years: 1712-1716 – Page 22 James Horsley Sr. – Prince George’s County: 1717-c1720 – Page 32 James Horsley Sr. – Queen Anne’s County: 1721 Onward – Page 35 James Horsley Sr.’s Wife Mary Seward – Page 38 James and Mary Seward Horsley’s Children – Page 41 James Horsley Jr. – Page 41 Hannah Horsley – Page 42 Thomas Horsley – Page 43 Richard Horsley – Page 46 Another Possible Child of James Horsley Sr.? – Page 47 James Horsley Sr.’s Later Years – Queen Anne’s County – Page 47 James Horsley Sr.’s Widow Mary Seward Remarries – Page 50 James and Mary Seward Horsley’s Family Continues – Page 52 Endnotes – Page 53 PART II: Annotated TIMELINE of RECORDS for James Horsley Sr. – Page 70 Dale Grammar Hopper Statement – Page 102 General Research Notes – Page 106 Acknowledgements – Page 106 Horsley Family Tree Charts – Page 107 Bibliography – Page 109 Index – Page 116 3 JAMES HORSLEY SR. -

Descendants of Roper-107563 13 Apr 2005 Page 1

Descendants of Roper-107563 13 Apr 2005 Page 1 1. Roper-107563 sp: Rebecca -107564 (b.Abt 1785-Bressingham,,Norfolk,England) 2. Edward Roper-270062 (b.Abt 1807-Bressingham,,Norfolk,England;d.2 May 1879-Banham,,Norfolk,England) sp: Rebecca Long-62850 (b.Bef 21 Mar 1784;m.11 Oct 1802) sp: Hannah Maria Gilbert-107555 (b.Abt 1808-Banham,,Norfolk,England;m.13 Apr 1824) 3. John Roper-120350 (b.Abt 1825-Banham,,Norfolk,England) sp: Sarah J -107558 (b.Abt 1823-Gorleston,,Suffolk,England) 4. Edward E Roper-272280 (b.Abt 1852-Banham,,Norfolk,England) 4. Anna M Roper-120351 (b.Abt 1858-Banham,,Norfolk,England) 4. Alfred Roper-272281 (b.Abt 1863-Banham,,Norfolk,England) 3. Eliza Roper-107556 (b.Abt 1829-Banham,,Norfolk,England) 3. Edward Roper Jr-107557 (b.Abt 1837-Banham,,Norfolk,England) sp: Emma -120424 (b.Abt 1833-Rishangles,,Suffolk,England) 3. Sarah Roper-107567 (b.Abt 1833-Fersfield,,Norfolk,England) 3. William Roper-107568 (b.Abt 1837-Bressingham,,Norfolk,England;d.29 Oct 1858) sp: Mary Gaymer-120478 (b.Abt 1838-Diss,,Norfolk,England;m.10 Nov 1858) 4. William Roper-270113 (b.1861-Shelfanger,,Norfolk,England) sp: Anna -271378 (b.Abt 1861-Bressingham,,Norfolk,England) 5. Zephaniah W Roper-271386 (b.Abt 1884-Ratcliffe,,Middlesex,England) 5. George Roper-271387 (b.Abt 1886-Mile End,,Middlesex,England) 5. Maude M Roper-271388 (b.Abt 1889-Mile End,,Middlesex,England) 5. Constance Roper-271389 (b.Abt 1892-Mile End,,Middlesex,England) 5. Frederick E Roper-271390 (b.Abt 1894-Mile End,,Middlesex,England) 4. -

STEPHEN TAYLOR the Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II

STEPHEN TAYLOR The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 129–151 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 5 The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II STEPHEN TAYLOR In the years between the Reformation and the revolution of 1688 the court lay at the very heart of English religious life. Court bishops played an important role as royal councillors in matters concerning both church and commonwealth. 1 Royal chaplaincies were sought after, both as important steps on the road of prefer- ment and as positions from which to influence religious policy.2 Printed court sermons were a prominent literary genre, providing not least an important forum for debate about the nature and character of the English Reformation. -

Wretharn, Otherwise Little Wretham, East

Wretharn, otherwise Little Wretham, East Wre- at his office in Cambridge ; and with the Clerk of tham, otherwise Great Wretham, Bridgeham, the Peace for the city and county of the city of otherwise Bridgham, Roudham, Larling, Snetter- Norwich, at his office in the city of Norwich ; and ton, Eccles, Wiiby, llargham, Attleborough, other- a copy of so much of the said plans, sections, and wise Attleburgli, Besthorpe, Wymondham, other- books of reference as relate to each of the parishes wise Wyndham, Hethersett, Kettartngham, Int- through which the proposed railway and branch wood, otherwise Intwoocl-cum-Keswick, Cringle- railway and works will pass, will be deposited, on ford, Keswick, Marketshall, otherwise Markshall, or before the thirty-first December next, with the Arniinghall, otherwise Arrneringhall, Trowse New- Parish Clerks of such parishes respectively, at their ton, Bexley, Thorpe, Caistor next Norsvich, Cais- respective residences. tor-cum-Markshall, otherwise Marketshall, Colney, Little Melton, Great Melton, Swardestone, Carl- Hayle Railway. ton Saint Peter, Carl ton Saint Mary, East Carlton, Mulbarton, otherwise Mulbarton-cum-Kenning- OTICE is hereby given, that application is ham, Bracon Ash, Hethel, Stanfield, Wicklewood, N intended to be made to Parliament in the "Wreningham, Ashwell Thorpe, Fundenhall, Old next session, for a Bill to alter, amend, and enlarge Buckenham, Shropham, Deopham, Larlingford, the powers and provisions of an Act, pa-ased in Great Eilinghara, Banham, Brettenham, East Har- the session of Parliament -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries.