An Oral History with Margaret B. Wilkerson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Mediagraphy Relating to the Black Man

racumEN7 RESUME ED 033 943 IE 001 593 AUTHOR Parker, James E., CcmF. TITLE A Eediagraphy Relating to the Flack Man. INSTITUTION North Carclina Coll., Durham. Pub Date May 69 Note 82F. EDRS Price EDRS Price MF-$0.50 BC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors African Culture, African Histcry, *Instructional Materials, *Mass Media, *Negro Culture, *Negro Histcry, Negro leadership, *Negro Literature, Negro Ycuth, Racial Eiscriminaticn, Slavery Abstract Media dealing with the Black man--his history, art, problems, and aspirations--are listed under 10 headings:(1) disc reccrdings,(2) filmstrips and multimedia kits, (3) microfilms, (4) motion pictures, (5) pictures, Fcsters and charts,(6) reprints,(7) slides, (8) tape reccrdings, (9) telecourses (kinesccFes and videotapes), and (10) transparencies. Rentalcr purchase costs of the materials are usually included, andsources and addresses where materials may be obtainedare appended. [Not available in hard cecy due tc marginal legibility of original dccument.] (JM) MEDIA Relatingto THE BLACKMAN by James E. Parker U.). IMPARIMUll OF !ULM,tOUGAI1011 &WINE OfFKE OF EDUCATION PeN THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON 02 ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS Ci STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION re% POSITION OR POLICY. O1 14.1 A MEDIAGRAPHY RELATING TO THE BLACK MAN Compiled by James E. Parker, Director Audiovisual-Television Center North Carolina College at Durham May, 1969 North Carolina College at Durham Durham, North Carolina 27707 .4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii FOREWORD iii DISC RECORDINGS 1-6 FILMSTRIPS AND MULTIMEDIA KITS 7- 18 MICROFILMS 19- 25 NOTION PICTURES 26- 48 PICTURES, POSTERS, CHARTS. -

Gospel Music and the Sonic Fictions of Black Womanhood in Twentieth-Century African American Literature

“UP ABOVE MY HEAD”: GOSPEL MUSIC AND THE SONIC FICTIONS OF BLACK WOMANHOOD IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE Kimberly Gibbs Burnett A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature in the Graduate School. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Danielle Christmas Florence Dore GerShun Avilez Glenn Hinson Candace Epps-Robertson ©2020 Kimberly Gibbs Burnett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kimberly Burnett: “Up Above My Head”: Gospel Music and the Sonic Fictions of Black Womanhood in TWentieth-Century African American Literature (Under the direction of Dr. Danielle Christmas) DraWing from DuBois’s Souls of Black Folk (1903), which highlighted the Negro spirituals as a means of documenting the existence of a soul for an African American community culturally reduced to their bodily functions, gospel music figures as a reminder of the narrative of black women’s struggle for humanity and of the literary markers of a black feminist ontology. As the attention to gospel music in texts about black women demonstrates, the material conditions of poverty and oppression did not exclude the existence of their spiritual value—of their claim to humanity that was not based on conduct or social decorum. At root, this project seeks to further the scholarship in sound and black feminist studies— applying concepts, such as saturation, break, and technology to the interpretation of black womanhood in the vernacular and cultural recordings of gospel in literature. Further, this dissertation seeks to offer neW historiography of black female development in tWentieth century literature—one which is shaped by a sounding culture that took place in choir stands, on radios in cramped kitchens, and on stages all across the nation. -

Lloyd Richards in Rehearsal

Lloyd Richards in Rehearsal by Everett C. Dixon A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Theatre Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario September 2013 © Everett Dixon, September 2013 Abstract This dissertation analyzes the rehearsal process of Caribbean-Canadian-American director Lloyd Richards (1919-2006), drawing on fifty original interviews conducted with Richards' artistic colleagues from all periods of his directing career, as well as on archival materials such as video-recordings, print and recorded interviews, performance reviews and unpublished letters and workshop notes. In order to frame this analysis, the dissertation will use Russian directing concepts of character, event and action to show how African American theatre traditions can be reformulated as directing strategies, thus suggesting the existence of a particularly African American directing methodology. The main analytical tool of the dissertation will be Stanislavsky's concept of "super-super objective," translated here as "larger thematic action," understood as an aesthetic ideal formulated as a call to action. The ultimate goal of the dissertation will be to come to an approximate formulation of Richards' "larger thematic action." Some of the artists interviewed are: Michael Schultz, Douglas Turner Ward, Woodie King, Jr., Dwight Andrews, Stephen Henderson, Thomas Richards, Scott Richards, James Earl Jones, Charles S. Dutton, Courtney B. Vance, Michele Shay, Ella Joyce, and others. Keywords: action, black aesthetics, black theatre movement, character, Dutton (Charles S.), event, Hansberry (Lorraine), Henderson (Stephen M.), Molette (Carlton W. and Barbara J.), Richards (Lloyd), Richards (Scott), Richards (Thomas), Jones (James Earl), Joyce (Ella), Vance (Courtney ii B.), Schultz (Michael), Shay (Michele), Stanislavsky (Konstantin), super-objective, theatre, Ward (Douglas Turner), Wilson (August). -

Performing Citizenship

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Performing citizenship: tensions in the creation of the citizen image on stage and screen John William Wright Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wright, John William, "Performing citizenship: tensions in the creation of the citizen image on stage and screen" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3383. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3383 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PERFORMING CITIZENSHIP: TENSIONS IN THE CREATION OF THE CITIZEN IMAGE ON STAGE AND SCREEN A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of Theatre by John William Wright B.A., Berry College, 1991 M.F.A., University of Georgia, 1995 December 2006 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS When I began my Doctoral studies in 1999, I had no idea of the long, strange journey I would encounter in completing this work. Seven years later, I enter my third year on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin-Manitowoc. Every day I am reminded as I teach that I have, all this time, remained a student myself. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Left of Karl Marx : the Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones / Carole Boyce Davies

T H E POLI T I C A L L I F E O F B L A C K C OMMUNIS T LEFT O F K A R L M A R X C L A U D I A JONES Carole Boyce Davies LEFT OF KARL MARX THE POLITICAL LIFE OF BLACK LEFT OF KARL MARX COMMUNIST CLAUDIA JONES Carole Boyce Davies Duke University Press Durham and London 2007 ∫ 2008 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Adobe Janson by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Preface xiii Chronology xxiii Introduction. Recovering the Radical Black Female Subject: Anti-Imperialism, Feminism, and Activism 1 1. Women’s Rights/Workers’ Rights/Anti-Imperialism: Challenging the Superexploitation of Black Working-Class Women 29 2. From ‘‘Half the World’’ to the Whole World: Journalism as Black Transnational Political Practice 69 3. Prison Blues: Literary Activism and a Poetry of Resistance 99 4. Deportation: The Other Politics of Diaspora, or ‘‘What is an ocean between us? We know how to build bridges.’’ 131 5. Carnival and Diaspora: Caribbean Community, Happiness, and Activism 167 6. Piece Work/Peace Work: Self-Construction versus State Repression 191 Notes 239 Bibliography 275 Index 295 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS his project owes everything to the spiritual guidance of Claudia Jones Therself with signs too many to identify. At every step of the way, she made her presence felt in ways so remarkable that only conversations with friends who understand the blurring that exists between the worlds which we inhabit could appreciate. -

Chicago Black Renaissance Literary Movement

CHICAGO BLACK RENAISSANCE LITERARY MOVEMENT LORRAINE HANSBERRY HOUSE 6140 S. RHODES AVENUE BUILT: 1909 ARCHITECT: ALBERT G. FERREE PERIOD OF SIGNIFICANCE: 1937-1940 For its associations with the “Chicago Black Renaissance” literary movement and iconic 20th century African-American playwright Lorraine Hansberry (1930-1965), the Lorraine Hansberry House at 6140 S. Rhodes Avenue possesses exceptional historic and cultural significance. Lorraine Hansberry’s groundbreaking play, A Raisin in the Sun, was the first drama by an African American woman to be produced on Broadway. It grappled with themes of the Chicago Black Renaissance literary movement and drew directly from Hansberry’s own childhood experiences in Chicago. A Raisin in the Sun closely echoes the trauma that Hansberry’s own family endured after her father, Carl Hansberry, purchased a brick apartment building at 6140 S. Rhodes Avenue that was subject to a racially- discriminatory housing covenant. A three-year-long-legal battle over the property, challenging the enforceability of restrictive covenants that effectively sanctioned discrimination in Chicago’s segregated neighborhoods, culminated in 1940 with a United States Supreme Court decision and was a locally important victory in the effort to outlaw racially-discriminatory covenants in housing. Hansberry’s pioneering dramas forced the American stage to a new level of excellence and honesty. Her strident commitment to gaining justice for people of African descent, shaped by her family’s direct efforts to combat institutional racism and segregation, marked the final phase of the vibrant literary movement known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. Born of diverse creative and intellectual forces in Chicago’s African- American community from the 1930s through the 1950s, the Chicago Black Renaissance also yielded such acclaimed writers as Richard Wright (1908-1960) and Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000), as well as pioneering cultural institutions like the George Cleveland Hall Branch Library. -

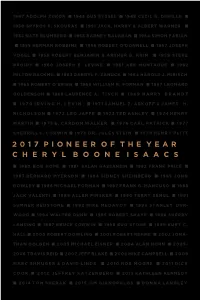

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

CORT THEATER, 138-146 West 48Th Street, Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 17, 1987; Designation List 196 LP-1328 CORT THEATER, 138-146 West 48th Street, Manhattan. Built 1912-13; architect, Thomas Lamb . Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1000, Lot 49. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Cort Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 24). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty witnesses spoke or had statements read into the record in favor of designation. One witness spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Cort Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in 1912- 13, the Cort is among the oldest surviving theaters in New York. It was designed by arc hi teet Thomas Lamb to house the productions of John Cort , one of the country's major producers and theater owners. The Cort Theater represents a special aspect of the nation's theatrical history. Beyond its historical importance, it is an exceptionally handsome theater, with a facade mode l e d on the Petit Trianon in Versailles. Its triple-story, marble-faced Corinthian colonnade is very unusual among the Broadway theater s. -

An Interactive Study Guide to Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies, and Bucks: an Interpretive History of Blacks in American Film by Donald Bogle Dominique M

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-11-2011 An Interactive Study Guide to Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Film By Donald Bogle Dominique M. Hardiman Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Hardiman, Dominique M., "An Interactive Study Guide to Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Film By Donald Bogle" (2011). Research Papers. Paper 66. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 AN INTERACTIVE STUDY GUIDE TOMS, COONS, MULATTOS, MAMMIES, AND BUCKS: AN INTERPRETIVE HISTORY OF BLACKS IN AMERICAN FILM BY DONALD BOGLE Written by Dominique M. Hardiman B.S., Southern Illinois University, 2011 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters of Science Degree Department of Mass Communications & Media Arts Southern Illinois University April 2011 ii RESEARCH APPROVAL AN INTERACTIVE STUDY GUIDE TOMS, COONS, MULATTOS, MAMMIES, AND BUCKS: AN INTERPRETIVE HISTORY OF BLACKS IN AMERICAN FILM By Dominique M. Hardiman A Research Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science in the field of Professional Media & Media Management Approved by: Dr. John Hochheimer, Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 11, 2011 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Research would not have been possible without the initial guidance of Dr. -

Reviews of the 1959 Play

● A Raisin in the Sun, 1959 Reviews By Roberta Cunha A Raisin in the Sun premiered at The Mandell Weiss Theatre at the La Jolla Playhouse and it also opened at the Barrymore Theatre in New York on March 11, 1959, running for 530 performances. Hansberry’s play was very popular and successful, and she won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for best play of the year, being the first Black woman to win this award, in 1960, and Hamberry’s play was also nominated for four Tony Awards: Best Play, Best Actor in a Play (Sidney Poitier), Best Actress in a Play (Claudia McNeil), and Best Direction of a Play (Lloyd Richards). One critic for the New York Times stated that A Raisin in the Sun “changed American theater forever” and represented a huge change for Black artists in the theater. The producers did not expect the play to become this popular and it received many mixed reviews by the audience, arguing that it was only for “African-American Experiences” and that it was not an universal play. In additional to that, in 1979 the play was restricted in a Utah school when it was criticized by an anti-pornography group, and in 2005, the play was also baned in an Illinois high school because principals argued that it is degrading to African Americans. Marylin Stasio, a critic from Variety Magazine, accentuates the importance of A Raisin in the Sun being the first play an African American woman to be produced on Broadway. The article further explains the play’s winning of the New York Drama Critics Circle’s award for best play, and how that also helps to bring attention to minorities. -

A Raisin in the Sun

2016-17 HOT Season for Young People Teacher Guidebook Nashville Repertory Theatre A Raisin in the Sun Sponsored by From our Season Sponsor For over 130 years Regions has been proud to be a part of the Middle Tennessee community, growing and thriving as our area has. From the opening of our doors on September 1, 1883, we have committed to this community and our customers. One area that we are strongly committed to is the education of our students. We are proud to support TPAC’s Humanities Outreach in Tennessee Program. What an important sponsorship this is – reaching over 25,000 students and teachers – some students would never see a performing arts production without this program. Regions continues to reinforce its commitment to the communities it serves and in addition to supporting programs such as HOT, we have close to 200 associates teaching financial literacy in classrooms this year. , for giving your students this wonderful opportunity. They will certainly enjoy Thankthe experience. you, Youteachers are creating memories of a lifetime, and Regions is proud to be able to help make this opportunity possible. Jim Schmitz 2016-17 Executive Vice President, Area Executive Middle Tennessee Area HOT Season for Young People WELCOME !N to the Arts 2016-2017 HOT Season for Young People Dear Teachers~ CONTENTS We are so pleased you will be attending Nashville Repertory The Playwright page 2 Theatre’s production of A Raisin in the Sun. Director René D. About the Play page 3 Copeland describes Lorraine Hansberry’s ground-breaking play as both specific and universal.