Proposals for the Co-Ordination of Formal Public Passenger Transport in the Johannesburg Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

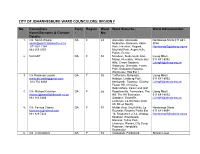

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Gauteng Provincial Government Pr33/2015 Isbn

ECE.indd 1 ESTIMATES OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE OF CAPITAL ESTIMATES GAUTENG PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT PR33/2015PR33/2015 ISBN: 978-0-621-43363-0ISBN: 978-0-621-43363-0 GAUTENG PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT 2/20/15 8:39:20 AM ESTIMATES OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE ECE.indd 2 ECE.indd 2 2/20/15 8:39:202/20/15 AM 8:39:20 AM ECE.indd 1 2/20/15 8:39:20 AM Estimates of Capital Expenditure ESTIMATES OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE i Estimates of Capital Expenditure The Estimates of Capital Expenditure 2015 report is compiled using the available information from different sources. Some of this information is subject to revision. To obtain additional copies of this document, please contact: The Head of Treasury Gauteng Provincial Government Private Bag X091, Marshalltown, 2107 Tel: 011 227 9004 PR33/2015 ISBN: 978-0-621-43363-0 Title of Publication : Estimates of Capital Expenditure 2015 - Gauteng Provincial Government ii Estimates of Capital Expenditure TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Executive Summary vii VOTE 4: HEALTH 1 VOTE 5: EDUCATION 53 VOTE 6: SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT 101 VOTE 8: HUMAN SETTLEMENT 116 VOTE 9: ROADS AND TRANSPORT 175 VOTE 11: AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT 205 VOTE 12: SPORT, RECREATION, ARTS AND CULTURE 215 VOTE 15: INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 223 iii Estimates of Capital Expenditure iv Estimates of Capital Expenditure Foreword Gauteng is not only the most populous province in South Africa, but also the most industrialised and the biggest contributor to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This has naturally led to inward migration, which places strain on social amenities as well as physical infrastructure. -

1 | Page A-Z PARTY HIRE CC 011-9071234 67 Charl Cilliers Ave

1 | P a g e A - Z PARTY HIRE CC 011- 9 0 7 1 2 3 4 67 Charl Cilliers Ave, Alberton North www.jumping.co.za [email protected] WE HIRE: Jumping castles and water slides Tables, table cloths, themed/plain overlace, runners (adults / kids) Chairs, chair covers, tie backs Photo character boards Happy birthday banners Party games Bubble machines, Smoke machines, chocolate fountains Popcorn, candy floss, slush puppy Crockery / Cutlery Themed Garden Boards Inflatable games Mechanical Bulls, Fufi Slides, Swings, shooting tunnels, dunk tanks, quad bikes, climbing walls Fancy Dress Costumes Picket Fencing Bean Bags etc etc We DO 3D / Scan / Cup / Wedding cakes Savoury & Sweet Platters / Sweet Kiddie Treats Party Packs Helium / air filled / foil balloons / Balloon décor Personalised birthday banners Party Accessories (cups, plates etc) Personalised Party cups, plates etc Pinatas Marquee Tents / Gazebos & Draping Stretch tents & decor Personalised colouring books etc etc WE ALSO MANUFACTURE AND REPAIR JUMPING CASTES, WATERSLIDES, GLADIATORS, CUSTOMISED INFLATABLES, PVC COVERS, TRAMPOLINES, TRAMPOLINE SAND BAGS, BOAT COVERS etc etc 2 | P a g e A - Z PARTY HIRE CC 011- 9 0 7 1 2 3 4 67 Charl Cilliers Ave, Alberton North www.jumping.co.za [email protected] Inflatables Our inflatables are check, cleaned and sanitised after each use Our inflatables are NOT for adult use Ground sheets available at no extra cost Prices below are for private birthday parties only, for corporate rates, please contact ushttp://WWW.JUMPING.CO.ZA -

THE ORDER of APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg Mpho Matsipa

THE ORDER OF APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg By Mpho Matsipa A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Nezar Alsayyad, Chair Professor Greig Crysler Professor Ananya Roy Spring 2014 THE ORDER OF APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg Mpho Matsipa TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgements ii List of Illustrations iii List of Abbreviations vi EAVESDROPPING 1 0.1 Regimes of Representation 6 0.2 Theorizing Globalization in Johannesburg 9 0.2.1 Neo‐liberal Urbanisms 10 0.2.2 Aesthetics and Subject Formation 12 0.2.3 Race Gender and Representation 13 0.3 A note on Methodology 14 0.4 Organization of the Text 15 1 EXCAVATING AT THE MARGINS 17 1.1 Barbaric Lands 18 1.1.1 Segregation: 1910 – 1948 23 1.1.2 Grand Apartheid: 1948 – 1960s 26 1.1.3 Late Apartheid: 1973 – 1990s 28 1.1.4 Post ‐ Apartheid: 1994 – 2010 30 1.2 Locating Black Women in Johannesburg 31 1.2.1 Excavations 36 2 THE LANDSCAPE OF PUBLIC ART IN JOHANNESBURG 39 2.1 Unmapping the City 43 2.1.1 The Dying Days of Apartheid: 1970‐ 1994 43 2.1.2 The Fiscal Abyss 45 2.2 Pioneers of the Cultural Arc 49 2.2.1 City Visions 49 2.2.2 Birth of the World Class African City 54 2.2.3 The Johannesburg Development Agency 58 2.3 Radical Fragments 61 2.3.1 The Johannesburg Art in Public Places Policy 63 3 THE CITY AS A WORK OF ART 69 3.1 Long Live the Dead Queen 72 3.1.2 Dereliction Can be Beautiful 75 3.1.2 Johannesburg Art City 79 3.2 Frontiers 84 3.2.1 The Central Johannesburg Partnership 19992 – 2010 85 3.2.2 City Improvement Districts and the Urban Enclave 87 3.3 Enframing the City 92 3.3.1 Black Woman as Trope 94 3.3.2 Branding, Art and Real Estate Values 98 4 DISPLACEMENT 102 4.1 Woza Sweet‐heart 104 4.1.1. -

SAARF OHMS 2006 Database Layout

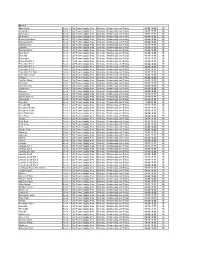

SAARF OUTDOOR MEASUREMENT SURVEY PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL Outdoor Database Layout South Africa (GAUTENG & KWAZULU-NATAL) August 2007 FILES FOR COMPUTER BUREAUX Prepared for: - South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF) Prepared by: - Nielsen Media Research and Nielsen Outdoor Copyright Reserved Confidential 1 The following document describes the content of the database files supplied to the computer bureaux. The database includes four input files necessary for the Outdoor Reach and Frequency algorithms: 1. Outdoor site locations file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Sites) 2. Respondent file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Respondents) 3. Board Exposures file (2 – Boards Exposure file) 4. Smoothed Board Impressions file (2 – Smoothed Board Impressions File) The data files are provided in a tab separated format, where all files are Window zipped. 1) Outdoor Site Locations File Format: The file contains the following data fields with the associated data types and formats: Data Field Max Data type Data definitions Extra Comments length (where necessary) Media Owner 20 character For SA only 3 owners: Clear Channel, Outdoor Network, Primedia Nielsen Outdoor 6 integer Up to a 6-digit unique identifier for Panel ID each panel Site type 20 character 14 types. (refer to last page for types) Site Size 10 character 30 size types (refer to last pages for sizes) Illumination hours 2 integer 12 (no external illumination) 24 (sun or artificially lit at all times) Direction facing 2 Character N, S, E, W, NE, NW, SE, SW Province 25 character 2 Provinces – Gauteng , Kwazulu- -

Historical Land Planning, Transport Poverty and Sustainable Cities: the Case of Johannesburg

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za (Accessed: Date). Historical land planning, transport poverty and sustainable cities: the case of Johannesburg Dr Michelle Claire Lawton Department of Geography, Environmental Management and Energy Studies Faculty of Science University of Johannesburg Mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree Masters of Science in Environmental Management Supervisor: Mrs Tracey J. McKay Co-Supervisor: Dr June Meeuwis December 2014 ANTI-PLAGIARISM DECLARATION University of Johannesburg Department of Geography, Environmental Management & Energy Studies Title: Dr Full name: Michelle Claire Lawton Student number: 909906451 Course: Mini dissertation MSc in Environmental Management 1. I understand what plagiarism is and am aware of the University’s policy in this regard. 2. I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is to present someone else’s ideas as my own. I know that I would plagiarise if I do not give credit to my sources, or if I lift sentences or paragraphs from a book, article or internet source without proper citation. -

Legend South View ! M Stop

± Halfway House Maroeladal Witkoppen Witkoppen Extensions Craigavon Bloubosrand Matika Paulshof Magaliessig Kleve Hill Sunninghill Megawatt Park Park Rivonia Petervale Gardens Woodmead Woodmead Ext Woodmead East Bryanston Rivonia Northgate The Woodlands Sharonlea W i l l i a m N Morningside i c o l D Manor r Sonneglans i v Strydom e Park Kelvin m Sundowner l M a e i o l v a l c i l i i i r b Bryanston N W D Morningside o n g West Ext 1 Wendywood w Kensington B Lyme W e D e Morning Side s L C Honeydew r t e Park i o o v A n r u e e v k g n Extentions Eastgate M e u ds A oodlan e W A A n n V a v v v e n v e l l u i a Avenue i e i e A u b e v l e h Eagle e n a n d D t t n e k n o A r u y a u r e e r n n u i u T e e e a o v e o u v g e i o o r e t f n i e Y n r R w r A i u S Canyon h e o u e u t a P t n r i a d v S n s e e p n an MB 9 - 7 a a H l A e r Hil v r o o an Hi S l P l K A v em H ! B ho a et R i Sc ns Stre S MB 7 - 20 tr t t R Sc A eet h F e s oe v e Sandown Marlboro m ! e r e a A K e ! t MB 8 - 14 n r MB 8 - 13 n MB 7 - 19 v e n S W M e r u ! e n k ! n i i e e n o r u 1 u rd e a 1 Strathavon e Harley a g r n th ch e g v 6 M e S Randburg r u a th tr Gra O n a St v ee ysto ! Street ve W re A t n ! A et MB 8 - 18 Driv MB 8 - 12! S e G B p S E ! MB 7 - 18 a r r a n s u a d G MB 7 - 17 r s Road St to t r F J d a rew n MB 8 - 17 a i And e y e a t St D s o e m ri S r t is R M ews ve o l n n T Andr 5 ! h MB 2 - 19 D n E r A t t r d o a r f ! h r i a b S S a n u v R v R a o a e e a o a i tr i ! Ruiterhof e m n n Wilgeheuwel b R e i n e e -

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors by Region, Suburbs and Political Party

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS BY REGION, SUBURBS AND POLITICAL PARTY No. Councillor Name/Surname & Par Region: Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Cotact Details: ty: No: 1. Cllr. Msingathi Mazibukwana ANC G 1 Streford 5,6,7,8 and 9 Phase 1, Bongani Dlamini 078 248 0981 2 and 3 082 553 7672 011 850 1008 011 850 1097 [email protected] 2. Cllr. Dimakatso Jeanette Ramafikeng ANC G 2 Lakeside 1,2,3 and 5 Mzwanele Dloboyi 074 574 4774 Orange Farm Ext.1 part of 011 850 1071 011 850 116 083 406 9643 3. Cllr. Lucky Mbuso ANC G 3 Orange Farm Proper Ext 4, 6 Bongani Dlamini 082 550 4965 and 7 082 553 7672 011 850 1073 011 850 1097 4. Cllr. Simon Mlekeleli Motha ANC G 4 Orange Farm Ext 2,8 & 9 Mzwanele Dloboyi 082 550 4965 Drieziek 1 011 850 1071 011 850 1073 Drieziek Part 4 083 406 9643 [email protected] 5. Cllr. Penny Martha Mphole ANC G 5 Dreziek 1,2,3,5 and 6 Mzwanele Dloboyi 082 834 5352 Poortjie 011 850 1071 011 850 1068 Streford Ext 7 part 083 406 9643 [email protected] Stretford Ext 8 part Kapok Drieziek Proper 6. Shirley Nepfumbada ANC G 6 Kanama park (weilers farm) Bongani Dlamini 076 553 9543 Finetown block 1,2,3 and 5 082 553 7672 010 230 0068 Thulamntwana 011 850 1097 Mountain view 7. Danny Netnow DA G 7 Ennerdale 1,3,6,10,11,12,13 Mzwanele Dloboyi 011 211-0670 and 14 011 850 1071 078 665 5186 Mid – Ennerdale 083 406 9643 [email protected] Finetown Block 4 and 5 (part) Finetown East ( part) Finetown North Meriting 8. -

Updated Efuel Site List

eFuel Site List - April 2019 Province Town Merchant Name Oil Company Address 1 Address 2 Telephone EASTERN CAPE ALGOA PARK PE MILLENNIUM CONVENIENCE CENTRE ENGEN CNR UITENHAGE & DYKE ROAD ALGOA PARK 041-4522619 EASTERN CAPE ALICE MAVUSO MOTORS ENGEN 792 MACNAB STREET ALICE 043-7270720 EASTERN CAPE ALIWAL NORTH ALIWAL AUTO VULSTASIE ENGEN 103 SOMERSET STREET ALIWAL NORTH 051-6342622 EASTERN CAPE AMALINDA EL CALTEX AMALINDA CALTEX 29 MAIN ROAD AMALINDA 043-7411930 EASTERN CAPE BEACON BAY EL BONZA BAY CONVENIENCE CENTRE ENGEN 45 BONZA BAY BEACON BAY 043-7483671 EASTERN CAPE BHISHO BHISHO MOTORS SHELL 658 INDEPENDENCE BOULEVARD BHISHO 040-6391785 EASTERN CAPE BHISHO RAITHUSI SERVICE STATION CALTEX 8908 MAITLAND ROAD BHISHO 043-6436001 EASTERN CAPE BHISHO UBUNTU MOTORS ENGEN CNR PHALO & COMGA ROADS BHISHO 040-6392563 EASTERN CAPE BLUEWATER BAY PE BLUE WATER BAY CENTRE ENGEN CNR HILLCREST & WEINRONK WAY BLUEWATER BAY 041-4662125 EASTERN CAPE BURGERSDORP KIMJER MOTORS BURGERSDORP ENGEN 37 PIET RETIEF STREET BURGERSDORP 051-6531835 EASTERN CAPE CENTRAL PE RINK AUTO CENTRE ENGEN 44 RINK STREET CENTRAL 041-5821036 EASTERN CAPE CRADOCK OUKOP MOTORS CALTEX 1 MIDDELBURG ROAD OUKOP INDUSTRIAL AREA 048-8811486 EASTERN CAPE CRADOCK STATUS DRIVEWAY CRADOCK ENGEN MIDDELBURG ROAD OUKOP INDUSTRIAL AREA 048-8810281 EASTERN CAPE CRADOCK TOTAL CRADOCK (CORPCLO) TOTAL 24 VOORTREKKER STREET CRADOCK 048-8812787 EASTERN CAPE DESPATCH TOTAL DESPATCH TOTAL 78 BOTHA STREET DESPATCH 041-9333338 EASTERN CAPE DUTYWA TOTAL DUTYWA TOTAL RICHARDSON ROAD DUTYWA 047-4891316 -

40942 30-6 Legal A

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA June Vol. 624 Pretoria, 30 2017 Junie No. 40942 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 40942 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 40942 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 30 JUNE 2017 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Free State / Vrystaat ........................................................................................................................ 14 KwaZulu-Natal ................................................................................................................................ 14 Limpopo ....................................................................................................................................... 15 Mpumalanga .................................................................................................................................. 15 North West / Noordwes .................................................................................................................... -

Legend Haddon Moroka Wes-Turffontein ! S Stop Gillview

± Maroeladal Witkoppen Witkoppen Extensions C e d a r M A a v l e i n b u o e n g Witko w ppen e Roa D d Craigavon d d a a r o N SS 1 - 19 ! i v R S e o e d r R d t ! n r i SS 1 - 20 r e n e e o b e i e e r f l W ! e r t v s m v i i e Matika M i r e a t R ! l l SS 1 - 21 n L o h d a Bloubosrand a l D i a Av e l a x a i t f v b W SS 1 - 18 rive m scen o o i er D re e r r o fish C d R SS 1 - 17 ng d e a Ki D n N r a ! W a g l g n o d e i o G n e l p ! c p a w D R o R a u e itk o SS 1 - 22 l o A e W o f n w d l f h a n R L u e e R o i i c x D R D r Paulshof e m v i g a o h a r G d e r a A k i l U a t i M o e u M v a e v R ll d w u e ! SS 1 - 16 s r e ! e y t k Magaliessig n D s o SS 1 - 23 M p a t r E i R i N e v l R SS 1 - 24 o c e e o N r a l Sunninghill a e t SS 1 - 25 i Megawatt w d f d ! f S m R a SS 1 - 15 r d ! in ) o k r e b Park a a t Kleve t g e t i o t d t ! t ! SS 1 - 26 r r f e n g e M e ( u o e o d e k f l n t e b r i i r u n l e F t r Hill m a r s t n a r e a a !n e e l S a T w W P d l SS 1 - 27 e s S r itko n p M t p a t H B i o pen d v n e p y d Petervale B u Rivonia Road l o a p r r B ! a d o d e Park A O R k a r a p h R it o i S SS 1 - 31 o o h o SS 1 - 28 J n h R t a W c Gardens W ! SS 1 - 32 R t SS 1 - 29 c e d e ! o i ! s r Woodmead t r a e B er r ! SS 1 - 14 d u y n P p t a h s S s Pert C h h Woodmead t r Road d o n Woodmead East N la Ext r Van Re a enen e i W b n A C ve r nue t o m r h e a e t e l u v ! l t e i r A s h e u r r t u e o o R t c le A r Bryanston SS 1 - 30 r v v e o N enu M S e a N n l t ! SS 1 - 13 l -

Load Shedding Schedules

Block 1 Abbotsford Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Alexandra Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Atholl East Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Birdhaven Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Bramley Gardens Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Bramley North Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Chislehurston Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Dunkeld Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Dunkeld West Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B East Bank Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Elton Hill Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Ennerdale Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Ennerdale Ext 1 Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Ennerdale Ext 2 Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Ennerdale Ext 3 Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Ennerdale Ext 4 Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Ennerdale Ext 5&6 Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday and Friday 06.00-10.00 1B Ennerdale South Block 1 City Power Supply Area Monday, Wednesday