Swimming with Animals Using Simple Swimming Lessons to Foster Connections to Other Life Forms and Appreciation of What They Have to Teach Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring Schedule 2020

Northeastern Aquatic Center SPRING SCHEDULE 2020 goal in the Beginner level is to get your child to Learn to Swim Program jump in, surface on the back, swim across the pool, and grab the opposite wall—all without being • Session 1: March 2 – March 12 touched by the teacher. • Session 2: March 16 – 26 • Session 3: March 30 – April 9 • Session 4: April 13 – 23 Advanced Beginner: If your child cannot swim freestyle, breathing to the side for a distance of 40 feet or more, this is the level for your child. We will ➢ Classes meet for 45-55 minutes in small groups evaluate all Advanced Beginners the first day to divide them into one of three categories (but for ➢ Lessons are Monday – Thursday for two now you choose Advanced Beginner): consecutive weeks (8 total classes). (1) Ages 5 and under—who have successfully completed our Beginner program ➢ Classes are offered 5:30-6:30 & 6:30-7:30 pm and swim successfully on their backs. In this level, children will have their back swimming skills reinforced— this is their safety position— while gradually teaching them to roll over onto Fees and Registration their front and take freestyle arm strokes. This (Learn to Swim Program) encourages a natural rolling motion, rather than the head out style found in dog paddle or with RESIDENT $65 floatation devices, will be used for them to NON-RESIDENT $75 breathe. And they’ll always have their back swimming skills for self-rescue. • In-person registration for residents and (2) Novice—who are age 6 and older, but are nonresidents is scheduled for absolute beginners. -

Mic 60-4090 GRUTZMACHER, Jean. an EVALUATION of THREE

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received Mic 60-4090 GRUTZMACHER, Jean. AN EVALUATION OF THREE EXPERIMENTAL METHODS OF TEACHING SWIMMING TO BLIND AND PARTIALLY SEEING CHILDREN. The Ohio State University, Ph. D ., 1960 Education, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan *■* . AN EVALUATION OF THREE EXPERIMENTAL METHODS OF TEACHING SWIMMING TO BLIND AND PARTIALLY SEEING CHILDREN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By JEAN GRUTZMACHER, A.B., M.A. The Ohio state University 1960 Approved by / {Q. Adviser Department of Physical Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express her appreciation to the many persons who have contributed to the development of this dissertation: Dr. W. G. Scarberry, Superintendent; Mrs. Hazel Weber, Elementary Principal; Mrs. Charles Grove, Girls Physical Education Instructor; and the Parent Teacher Association of The Ohio State School for the Blind; Mr. Milton Overholt and his daughter Patti, who helped develop the swimming skill chart; the forty-four children who participated in the experimental swimming program and the student teachers. The writer also would like to thank Dr. Charles E. Buell, California state School for the Blind; Misses Jeanne Kenmore and Helde Lende, The American Foundation for the Blind; Dr. Margaret Mordy, Department of Physical Education for women, The Ohio State University; Dr. Willard P. Ashbrook, Department of Physical Education for Men, The Ohio State University, and John Dobos for the photography; Mrs. Beverly Schober Hay for typing efforts; and the Women's National Aquatic Forum for the presentation of the Hazel Wilbraham Research Grant. -

An Experimental Testing of Ability and Progress in Swimming Walter J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1933 An experimental testing of ability and progress in swimming Walter J. Osinski University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Osinski, Walter J., "An experimental testing of ability and progress in swimming" (1933). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1852. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1852 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J883 DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD M268 1933 0825 "AN EXPERIMENTAL TESTING OP ABILITY AND PROGRESS IN SWIMMING." By Walter J. Osinskl "Thesis Submitted For Degree of Master of Science." Massachusetts State College, Amherst. 1933 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Page Terminology and definitions. •••• • 1 Limi -cation of exporiment • , • • ••«•••«• 5 Limitations of statistics. 4 ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF S'A'IEMING Historical excerpts.... • •••• 5 SURVEY OF SV.T .L ING LITERATURE History of testing in swimr.i5.ng «•••••..« 21 MATERIALS AND METHODS Development of tests* # •,••••••.,,* ..*•*••• 25 Test one. ••,,.».•• » »...•• »•• 26 Test two,... ............ •#••••##• 26 Test throe. •••• •••••#••••••••••••••»•• 27 Test four • ^ Test five 28 Test six, •*,,. ...*•••• • • 28 Method of procedure ,,,«• • • • 29 INTERPRETATION OF DATA Collection of data 34 Chart of entire experimental group,.,. • 37 Leg test of experimental group..... 38 Table I (leg test) 40 Graph I (leg test) 41 Page Collection of data (continuied) • Arm test of experimental group. ••••••• 42 Table II (arm tc st )••...••.«• 44 Graph II (arm test).. -

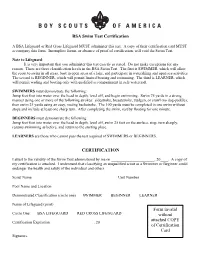

BSA Swim Test Certificate

BSA Swim Test Certification A BSA Lifeguard or Red Cross Lifeguard MUST administer this test. A copy of their certification card MUST accompany this form. Incomplete forms, or absence of proof of certification, will void the Swim Test. Note to Lifeguard: It is very important that you administer this test exactly as stated. Do not make exceptions for any reason. There are three classification levels in the BSA Swim Test. The first is SWIMMER, which will allow the scout to swim in all areas, boat in open areas of a lake, and participate in waterskiing and open sea activities. The second is BEGINNER, which will permit limited boating and swimming. The third is LEARNER, which will permit wading and boating only with qualified accompaniment in safe watercraft. SWIMMERS must demonstrate the following: Jump feet first into water over the head in depth, level off, and begin swimming. Swim 75 yards in a strong manner using one or more of the following strokes: sidestroke, breaststroke, trudgen, or crawl (no dog-paddle); then swim 25 yards using an easy, resting backstroke. The 100 yards must be completed in one swim without stops and include at least one sharp turn. After completing the swim, rest by floating for one minute. BEGINNERS must demonstrate the following: Jump feet first into water over the head in depth, level off, swim 25 feet on the surface, stop, turn sharply, resume swimming as before, and return to the starting place. LEARNERS are those who cannot pass the test required of SWIMMERS or BEGINNERS. CERTIFICATION I attest to the validity of the Swim Test administered by me on ______________________, 20____. -

Download the Swim & Safety Program

Swim ogram KL & PO OG C IN D L r R U G S A E P F D aTfety 6-18 Months 19-36 Months 4–6 Months Water familiarisation Water familiarisation Water familiarisation Breath control Submerge with recovery to surface How to hold your child Unaided freefall Jumping into the pool and kicking Coordination & breath control Submerging to the surface Parental bonding & lots of fun Holding onto pool edge Independent swimming with floats Floating on back with assistance Back Float with floats Climbing out of the pool unaided AHORS NGUI SEAL SE E PE N A solo swim/dog paddle 4 Years with arm floats Safe entry & exit from pool Safe entry & exit from pool 15 metre swim/dog paddle Water awareness Freestyle & backstroke kicking without a pod board with arm floats Breath control & submerging 5 large freestyle arms Pushing off the bar and swimming Floating on back in shallow & deep water without arm floats Jumping in the deep end and Dog paddle/action in deep water, jumping 10 metre swim without arm floats recovering back using dog and returning to wall paddle/action sculling Floating on back without floats Freestyle kicking with a board Floating on back with Jump in and return to bar solo Backstroke kicking with a board recovery to wall Swim ogram RF & RL PH A IS A IN r L I T H M P O N S D S afety Freestyle & Backstroke swimming Safe entry & exit from pool Full freestyle & backstroke in shallow building stroke & strength water progressing to deep water Freestyle breathing on board Breaststroke arms with dolphin kick & fins Floating/dog paddle Backstroke on -

Aquanaut.Pdf

Preparation for: 1-2 Meetings or Webelos Camp Takeaways 2nd Class Scout Rank Req 5a-d Improving water safety 1st Class Scout Rank Req 6a knowledge Swimming Merit Badge Developing aquatics skills Aquanaut A Scout is obedient Complete 1–4 and at least two others. 1. State the safety precautions you need to take before doing any water activity. 2. Discuss the importance of learning the skills you need to know before going boating. 3. Explain the meaning of “order of rescue” and demonstrate the reach and throw rescue techniques from land. 4. Attempt the BSA swimmer test. 5. Demonstrate the precautions you must take before attempting to dive headfirst into the water, and attempt a front surface dive. 6. Learn and demonstrate two of the following strokes: crawl, sidestroke, breaststroke, or elementary backstroke. 7. Invite a member or former member of a lifeguard team, rescue squad, the U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Navy, or other armed forces branch who has had swimming and rescue training to your den meeting. Find out what training and other experiences this person has had. 8. Demonstrate how to correctly fasten a life jacket that is the right size for you. Jump into water over your head. Show how the life jacket helps keep your head above water by swimming 25 feet. Get out of the water, remove the life jacket and hang it where it will dry. 9. If you are a qualified swimmer, select a paddle of the proper size and paddle a canoe with an adult’s supervision. Things you will need for this activity badge: 1. -

Teacher Guide Teaching Survival Strokes

Teacher Guide: Teaching Survival Strokes Survival swimming is based on low energy principles where the arms do not leave the water on recovery and the head is above the water giving full vision. The object of survival swimming is to reduce energy output to increase chances of survival in any conditions even when fully clothed. Traditionally freestyle is taught first in association with backstroke and this is often followed by breaststroke. The teaching sequence, regardless of stroke, can be described with the acronym FLAB – Floating in the streamlined position, Legs, Arms and then Breathing. Even though breaststroke is a competition stroke, it fits within the description of a survival stroke. Other survival stokes include dog paddle, sculling, back survival stroke and side stroke. Back survival stroke can be very useful when kicking away from rocks or for towing a drowning victim to safety. The teaching processes This guide is concerned with the basic teaching sequence to develop breaststroke, back survival stroke and side stroke. Information on activities and techniques to refine breaststroke is available from Swimming New Zealand. A sequence for teaching breaststroke Breaststroke leg action should be taught dry first. This can be done in the classroom before going to the pool. • Lying across a chair bring the heels up to the hips – drop the knees • Turn feet outwards • Circle feet down and back to glide position • Hold glide position and repeat The feet can be manipulated by a buddy while the buddy is talking through the actions. Then the student can do this on their own with the buddy watching and peer assessing. -

Klahanie Association – Aquatics Department Swim Lesson Program – 2017

Klahanie Association – Aquatics Department Swim Lesson Program – 2017 *Please review each level, as Klahanie’s swim program has been revised to offer a more comprehensive, streamlined program for residents. Parent Child Class: Ages 6 months – 3 years (parent/adult in water with child) Preschool Classes: Ages 3 – 5 years Beginner, Intermediate, & Advanced Classes: Ages 6+ years Parent Child Ages: 6 months – 3 years Prerequisite: parent or adult must accompany child in the water Course Objectives: - Enter/exit water safely (with or without assistance) - Blow bubbles on surface of water - Explore submerging mouth, nose & face - Intro to front and back floats - Into to front and back kicks - Into to alternating arm action - Jump in from side with help Preschool I Ages: 3 – 5 years Prerequisite: none Course Objectives: - Blow bubbles 5 seconds - Fully under water 3 seconds - 10 second assisted front float - 10 second assisted back float - Front float to standing recovery - Assisted front to back float transition - Assisted front kick - Assisted back kick - Intro to bobbing - Intro to dog paddle - Intro to front crawl - Intro to backstroke Preschool II Ages: 3 – 5 years Prerequisite: Demonstration of Preschool I course objectives Course Objectives: - Blow bubbles 10 seconds - 10 independent bobs – fully submerged - 10 second independent front float - 10 second independent back float - Independent front to back float transition - 5m dog paddle w/ bobbing - 5m front crawl - 5m assisted, relaxed backstroke - 5m front kick - 5m back kick Preschool -

Common Disqualifications

COMMON DISQUALIFICATIONS FREESTYLE BREASTSTROKE Failure to touch at the turn. (NOTE: if Body not on breast when beginning first touch missed, swimmer may scull back arm pull following start or turn. and make a legal touch or may come Arms not in the same horizontal plane back if he/she missed the wall, but only on first arm pull. in freestyle.) Raise hand when At the start or after any turn, head still observed. below the water surface when the hands Walking or springing from the bottom begin to turn inward at the widest part of the pool. of the second arm stroke . Finishing in the wrong lane. Arm pull past hipline except for the first Getting artificial assistance (e.g., pulling pull at the start or after a turn on lane lines or pushing off side walls.) Over-the-water recovery with elbows out of the water (except at the turn or BACKSTROKE finish). Sidestroke or scissors kick (any Standing in or on the gutter at the alternating movement). starting signal (Starter's call).[NOTE: Butterfly kick other than prior to the Toes may be curled over the gutter in first breaststroke kick after the start or the NVSL!] turn. Swimmer submerged after start or turn Touch not simultaneous or one-hand and head surfacing beyond 15 meters touch on turns or finish. (Need not be on (16.4 yards). the same level.) Getting artificial assistance. Flutter or scissors kick Turning shoulders past vertical on the Body not at or past the vertical towards turn and, after pulling forward with arm the breast when swimmer leaves wall already in motion, then either gliding after a turn. -

No Stroke First!

International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education Volume 8 Number 1 Article 2 2-1-2014 Which Stroke First? No Stroke First! Robert Kieg Stallman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare Recommended Citation Stallman, Robert Kieg (2014) "Which Stroke First? No Stroke First!," International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.08.01.02 Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ijare/vol8/iss1/2 This Editorial is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Stallman: Which Stroke First? No Stroke First! International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 2014, 8, 5-8 http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/ijare.2014-0040 © 2014 Human Kinetics, Inc. Which Stroke First? No Stroke First! Robert Keig Stallman, Guest Editor Our editor-in-chief eloquently addressed the question above in his editorial in the November 2013 issue [7(4)] of the International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education. He was asked whether he had an opinion, and he certainly did! Thank you very much, Professor Langendorfer. I also have an opinion (equally long and abiding as Professor Langendorfer). I share my opinion with our readers to support the previous editorial. But, I also feel the need to add several comments to those of the previous editorial. In spite of the fact that this may be the most often asked question related to the teaching of swimming, I consider it to be long-outdated, unnecessary, and irrelevant – in other words, not only is it the wrong question, but it ought to be a non-question! No Stroke First! – All Strokes First! This subtitle is taken from an article I wrote some years ago in which I first char- acterized this issue as outdated. -

Why Aquatic School? Registration

Registration 03873 NH Sandown, BOX 436, Center, PO Learning Playmates to: section return and off this tear Please Child ___________________________ Parent _________________________ Address ________________________ _______________________________ Home Telephone _________________ Other Telephone _________________ Date of Birth _____________________ Age as of 6/26/2017_______________ E-Mail Address: Why Aquatic School? ________________________________ Aquatic School Child’s Swimming Experience Playmates Learning Center saw a need for Still Afraid of the Water _____ Loves Water but Cannot Dog Paddle _____ children to learn to swim at an early age. Children Ages 5 months- 10 years Able to Dog Paddle _____ New Hampshire has many beautiful ponds Can Swim in Deep End w/ Bubble _____ and lakes for families to enjoy. More people Can Swim in Deep End w/o Bubble _____ have swimming pools in their back yards. Needs to Improve Strokes _____ Session 1 __Session 2 __Session 3__Session 4__ SESSION 1 (Mon/Wed) = June 26 - July 19 PLEASE note any traumatic water experiences Children should be familiar with safety rules here: around water. The earlier they learn to SESSION 2 (Tues/Thurs) = June 27 - July 20 _____________________________________ swim, the safer they will be in and around SESSION 3 (Mon/Wed) = July 24 - Aug 16 ______________________________________ water. We installed an in-ground pool behind our facility to meet this need. SESSION 4 (Tues/Thurs) = July 25 - Aug 17 ______________________________________ I/we are aware that participation in this program may present a strain on my child's body, or its parts and DISCLAIMERS therefore represent to Playmates Learning Center that to We will do our best to the best of my knowledge, my child is in proper physical condition to allow him/her to participate and I/we assume accommodate the class times for the risk of participating. -

SCIENCE in SWIMMING II Edited by Krystyna Zatoñ and Marcin Jaszczak

Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego we Wroc³awiu SCIENCE IN SWIMMING II Edited by Krystyna Zatoñ and Marcin Jaszczak Wroc³aw 2008 EDITORIAL BOARD Tadeusz Bober (Editor-in-chief), Bogus³awa Idzik (Secretary), Gabriel £asiñski, Alicja Rutkowska-Kucharska, Jan Szczegielniak, Edward Wlaz³o, Zdzis³awa Wrzosek, Marek Zatoñ REVIEWERS Ewa Dybiñska, Marek Zatoñ PROOFREADING Zofia Prele Stanis³awa Trela COVER DESIGN Marek Rejman Anna Miecznikowska TYPESETTING Anna Miecznikowska Publication subsidised by Marshal Office of Lower Silesia. © Copyright by Wydawnictwo AWF Wroc³aw, 2008 ISBN 978-83-89156-78-5 Wydawnictwo Akademii Wychowania Fizycznego we Wroc³awiu 51-684 Wroc³aw, ul. Adama Mickiewicza 98 [email protected] Edition I. Print: Sowa – Druk na ¯¹danie CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 5 PART ONE SWIMMING EDUCATION Agnieszka Jastrzêbska and Bartosz Ochmann Differences in Level of Kinaesthetic Sense Between Swimmers and Non-Swimmers .... 9 Andrzej Klarowicz, Krystyna Zatoñ and Piotr Albiñski Differences in Conscious Reception of Stimuli from Water Environment in School Children ......................................................................................................... 16 Alicja Stachura, £ucja P³atek and Micha³ Skóra The Effectiveness of the Process of Learning Swimming Skills in 7-year-old Children .................................................................................................... 23 Zbynek Svozil and Filip Neuls