Life Insurance Regulators Should Block Cost of Insurance Rate Increases When Used to Avoid Guaranteed Interest Rates in Universal Life Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transamerica-Universal-Life.Pdf

Everybody deserves a better tomorrow. TransElite® Universal Life Insurance | Underwritten by Transamerica Life Insurance Company TransElite® is universal life insurance that helps provide fi nancial Product Highlights protection at a competitive cost. • No Physicals or Blood work Help protect the people who depend on you. • Accumulates Cash Value Andrea chose universal life insurance because she didn’t want to worry • Guaranteed 3% Interest Rate what would happen to her fi ve-year-old, Samuel, in the event of her death. It helped her feel better about his well-being to know her life insurance • Withdrawal and Loan Options death benefi t would help him if the worst happened. • Convenient Payroll Deduction Universal life insurance can help safeguard your family members’ futures, with benefi ts that can assist with your fi nal expenses and their dependent Contact Information care, living expenses or college tuition. VISIT Give yourself peace of mind. transamericabenefits.com Only 44 percent of American households have individual life insurance —that’s the lowest number in half-a-century. The good news is that half CUSTOMER SERVICE of all households realize they need more.1 1-888-763-7474 Get the benefi ts that fi t your needs. Andrea is doing her best to save for retirement. Her universal life insurance policy builds cash value2 so she can borrow against it in the future and protect her savings if an unexpected expense arises. In her later years, her built-up cash value will continue to pay her cost of insurance, maintaining her policy even after she retires. Life insurance should fi t you, and we don’t limit you with a one-size-fi ts-all approach. -

No. 18-2675 NICHOLAS LOMMA

Case: 18-2675 Document: 003113368559 Page: 1 Date Filed: 10/08/2019 NOT PRECEDENTIAL UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT ______________ No. 18-2675 ______________ NICHOLAS LOMMA; J. L., a Minor, by Anthony Lomma, Guardian v. OHIO NATIONAL LIFE ASSURANCE CORPORATION; OHIO NATIONAL LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY, Appellants ______________ Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania (D.C. No. 3-16-cv-02396) District Judge: Hon. Robert D. Mariani ______________ Submitted Pursuant to Third Circuit L.A.R. 34.1(a) October 1, 2019 ______________ Before: SHWARTZ, FUENTES, FISHER, Circuit Judges. (Filed: October 8, 2019) ______________ OPINION* ______________ SHWARTZ, Circuit Judge. * This disposition is not an opinion of the full Court and, pursuant to I.O.P. 5.7, does not constitute binding precedent. Case: 18-2675 Document: 003113368559 Page: 2 Date Filed: 10/08/2019 Defendants Ohio National Life Assurance Corporation and Ohio National Life Insurance Company appeal the District Court’s order granting summary judgment to Plaintiffs Nicholas Lomma and J.L., a minor, by his father and guardian, Anthony Lomma, on their claim for breach of contract based on Ohio National Life Assurance’s denial of death benefits pursuant to a suicide exclusion in a life insurance policy for which they are beneficiaries. Because the language of the suicide exclusion unambiguously limits coverage to premiums paid where the insured commits suicide within the first two years of the policy, we will reverse. I A In 1986, Pennsylvania National Life Insurance Company issued Lora Marie Lomma a universal life insurance policy for $25,000 in coverage (“Universal Policy”). -

Universal Life Insurance

UNIVERSAL LIFE INSURANCE Universal life insurance (UL) adds a layer of security to policies with the ability DEATH BENEFIT OPTIONS to combine death protection with savings, and a layer of convenience with The death benefit at time of policy issue is the initial face amount. adjustable premiums and payment schedules. Premiums are paid to the insurance company. The insurance company subtracts the cost of insurance Policyholders have two options: and other expenses each month. It then credits interest in a cash accumulation OPTION 1 (LEVEL) account. And UL policies are transparent. By reviewing the annual statement, The death benefit until age 100 and beyond is equal to the face amount. policyholders can monitor the cash value growth in the policy and see the expenses and the interest crediting rate. As long as the cash surrender value is OPTION 2 (INCREASING) sufficient to pay the annual costs of insurance, policyholders can actually skip a The death benefit until age 100 is equal to the face amount plus the cash premium, or reduce or increase the premium. surrender value. THE TWO MOST COMMON TYPES OF UNIVERSAL LIFE ARE AUL AND GUL WHAT IS LOW-LOAD LIFE INSURANCE? Each policy has a face amount, scheduled premiums, and builds up cash value on Low-load life insurance is insurance sold without the typical agent a tax deferred basis. Here’s where they differ: commissions. That allows for lower expenses for marketing, sales, and administration. And unlike traditional UL, the policy begins to build cash value immediately without any surrender charges. All other aspects of Accumulation Universal Life (AUL): AUL policies have flexible premiums low-load life insurance solutions mirror traditional life insurance. -

A New Age: Life Insurance Securitisation

A new age: life insurance securitisation By Perry J. Shwachman, Anthony J. Ribaudo and R. Bradley Drake, Sidley Austin LLP In the past five years, the United States life insurance industry has begun a new phase in its management of risk. The industry has adopted and developed securitisation techniques to address challenges raised by its regulatory regime and strengthen return on equity. At the same time, securitisation has provided investors the ability to receive exposure to risks uncorrelated with traditional investments. To date the life insurance industry has utilised three basic securitisation transaction types: redundant reserve, embedded value and catastrophic mortality. Redundant reserve securitisations have grown most party investors. In a typical XXX or AXXX rapidly in recent years, in response to the adoption in securitisation, the insurer cedes, through reinsurance, the United States of Regulation XXX and Actuarial the risks related to an identifiable pool of insurance Guideline AXXX. From the insurers’ perspective, these policies to a special purpose vehicle that is usually regulations have substantially increased the reserves licensed as a captive reinsurer. This reinsurer is that life insurers are required to maintain in financed through its sale of securities. The securities connection with level-premium term life insurance may be in the form of true equity sold to an policies and ‘no lapse’ or ‘secondary’ guarantees for intermediary holding company which issues debt to universal life insurance policies.These additional investors or in the form of surplus notes directly reserves are considered redundant to the reserves issued to investors or issued to a trust which then that insurers believe will be required economically to issues debt securities. -

Protection They Need. Growth You Want. Intelligent Life® Universal Life Insurance Intelligent Life® Survivorship Universal Life Insurance

Protection they need. Growth you want. Intelligent Life® Universal Life Insurance Intelligent Life® Survivorship Universal Life Insurance Designed to meet a lifetime of needs As you move through life’s stages, there are different reasons to own life insurance for protection and peace of mind—buying a home, starting a family, planning for education expenses, starting or growing a business, retiring as you’d like and leaving a legacy. TIAA-CREF Life Insurance Company (TIAA Life) has designed the family of Intelligent Life® policies to be flexible enough to help keep pace with your evolving needs and help you provide financial support for your family or business if something unexpectedly happens to you. Lifetime protection plus more An Intelligent Life Universal Life® (UL) policy is permanent life insurance designed to protect one life or two, depending on your needs. These policies offer the protection of a death benefit payout if something should happen to the insured. Plus, the policy’s cash value earns interest—a minimum of 3%— inside our Fixed Account’s portfolio. Intelligent Life UL Death benefit is paid after the death of the insured Intelligent Life Survivorship UL1 Death benefit is paid after the death of the second insured Flexible payments: Flexible premium payments Simplicity: Our fees are simple, transparent and coverage amounts mean you can tailor your and easy to understand. There are no front- or coverage and payment as your needs change back-end sales loads or surrender charges.5 over time.2 This means more of your money goes to work for you. Growth potential: Any cash value in your policy earns interest daily based on the performance Tax advantages: Your beneficiaries generally of our Fixed Account investment’s portfolio. -

The Universal Life Insurance Policy

l . The Universal Life Insurance Policy James C. H. Anderson Published in EMPHASIS in November 1975. Reprinted with perraission from Tillinghast ~ A Towers Perrin Company. Editor's note: This issue of EMPHASIS breaks with tradition, since it represents not the collective view of the staff of Tillinghast & Company but the outlook of an individual staff member. James C. H. Anderson, president of the firm, presented the paper from which this article is taken before the Seventh Pacific Insurance Conference in Septem- ber 1975. Mr. Anderson's approach is provocative, and his perceptions may be con- troversial to some; but, in the current climate of concern over the future of the life insurance industry's traditional products and distribution systems, they deserve care- ful consideration. Here, then, is one man's blueprint for a "universal" life insurance policy --for what the author calls "a fully flexible alternative to conventional life insurance contracts, designed to meet the needs and demands of the life insurance market in 1975 and beyond." Purpose and Scope ... that it is not realistic for the industry to address the needs of the typical buyer with traditional perma- The purpose of this paper is not to present a revolu- nent life insurance products requiring fixed regular pre- tionary new concept; instead, it is to reexamine a famil- miums and providing fixed benefits, both expressed in iar concept in the fight of new market circumstances constant nominal dollars. and, to consider the consequences to the life insurance ... that the traditional life insurance industry distribu- industry if the concept were adopted. -

Model Regulation 787—Term and Universal Life Insurance Reserve

Model Regulation Service—1st Quarter 2017 TERM AND UNIVERSAL LIFE INSURANCE RESERVE FINANCING MODEL REGULATION TABLE OF CONTENTS: Section 1. Authority Section 2. Purpose and Intent Section 3. Applicability Section 4. Exemptions from this Regulation Section 5. Definitions Section 6. The Actuarial Method Section 7. Requirements Applicable to Covered Policies to Obtain Credit for Reinsurance; Opportunity for Remediation Section 8. Severability Section 9. Prohibition against Avoidance Section 10. Effective Date Section 1. Authority This regulation is adopted and promulgated by [title of supervisory authority] pursuant to [insert provision of state law equivalent to Section 5 of the Credit for Reinsurance Model Law] of the [name of state] Insurance Code. Section 2. Purpose and Intent The purpose and intent of this regulation is to establish uniform, national standards governing reserve financing arrangements pertaining to life insurance policies containing guaranteed nonlevel gross premiums, guaranteed nonlevel benefits and universal life insurance policies with secondary guarantees; and to ensure that, with respect to each such financing arrangement, funds consisting of Primary Security and Other Security, as defined in Section 5, are held by or on behalf of ceding insurers in the forms and amounts required herein. In general, reinsurance ceded for reserve financing purposes has one or more of the following characteristics: some or all of the assets used to secure the reinsurance treaty or to capitalize the reinsurer (1) are issued by the ceding insurer or its affiliates; or (2) are not unconditionally available to satisfy the general account obligations of the ceding insurer; or (3) create a reimbursement, indemnification or other similar obligation on the part of the ceding insurer or any if its affiliates (other than a payment obligation under a derivative contract acquired in the normal course and used to support and hedge liabilities pertaining to the actual risks in the policies ceded pursuant to the reinsurance treaty). -

One Policy, Two Benefits Your Group Variable Universal Life (GVUL) Policy Combines Valuable Life Insurance Protection with an Optional Investment Feature

Group Variable Universal Life One policy, two benefits Your Group Variable Universal Life (GVUL) policy combines valuable life insurance protection with an optional investment feature. So, in one policy, you can provide financial protection for your loved ones in the event of your death and build cash savings that you can use during your lifetime towards, for example, a child’s education, buying a home or living comfortably in retirement. Protection Savings Protection + Savings Life Insurance Investment Feature GVUL Life insurance Life insurance is an essential part of an overall financial plan. It’s important you plan ahead with enough life insurance coverage to help ensure a continued lifestyle for those who may depend on you. And, your financial plan doesn’t end when you “ Employees rely heavily on group life change jobs or retire, so it’s important to have life insurance that doesn’t end at that insurance, as evidenced by 71% of time as well. Your GVUL insurance coverage is an individually-owned and portable1 insurance proceeds coming from policy, which means you have the freedom to take it with you if you retire or leave the group policies.”2 company for any reason — at competitive group rates — keeping your financial plan intact to continue to provide your loved ones with valuable life insurance protection. Choose the right amount of life insurance coverage Update coverage as your needs change Providing financial protection to those who depend on you is important, but it Don’t forget as your life changes, so does your need doesn’t have to be difficult. -

Using Cash Value Life Insurance for Retirement Savings

One Resource Group 13548 Zubrick Road Roanoke, IN 46783 888-467-6755 [email protected] Using Cash Value Life Insurance for Retirement Savings August 03, 2017 Page 1 of 6, see disclaimer on final page Using Cash Value Life Insurance for Retirement Savings What is using cash value life insurance for retirement savings? One of the more popular uses for cash value life insurance is to save for retirement. Cash value life insurance refers to a wide variety of insurance policies that provide both a death benefit and the potential accumulation of cash value over a period of time. Cash value life insurance can range from a traditional level premium whole life policy to a single premium whole life policy to a universal life policy to a variable life insurance policy or a variable universal life policy . In today's insurance marketplace, there are a wide variety of cash value life insurance policies that a consumer can buy. These types of insurance policies are in contrast to a term life insurance policy in which the insured makes a series of premium payments and the beneficiaries collect the death benefit if the insured dies while the policy is still in effect. There is no buildup of cash value with a term life policy. Many people use a cash value life insurance policy to save for their retirement and to provide a death benefit to their beneficiaries. In very rare instances, companies may offer their employees an option under their retirement plan to purchase life insurance. Under a qualified retirement plan, amounts contributed to the plan by the employer will be tax deductible. -

7. Reinsurance

Syndicated Loans The primary credit indicator for syndicated loans is whether the loans are performing in accordance with the contractual terms of the syndication. Total nonperforming syndicated loans as of December 31, 2010 were $3 million. Consumer Bank Loans The Company considers the credit worthiness of borrowers (FICO score), collateral characteristics such as LTV and geographic concentration in determining the allowance for loan loss for residential mortgage loans, credit cards and other consumer bank loans. At a minimum, management updates FICO scores and LTV ratios semiannually. As of December 31, 2010, approximately 7% of residential mortgage loans and credit cards and other consumer bank loans had FICO scores below 640. At December 31, 2010, approximately 3% of the Company’s residential mortgage loans had LTV ratios greater than 90%. The Company’s most significant geographic concentration for the consumer bank loans is in California representing 33% of the portfolio as of December 31, 2010. No other state represents more than 10% of the total consumer bank loan portfolio. 7. Reinsurance Generally, the Company reinsures 90% of the death benefit liability related to almost all individual fixed and variable universal life and term life insurance products. As a result, the Company typically retains and is at risk for, at most, 10% of each policy’s death benefit from the first dollar of coverage for new sales of these policies, subject to the reinsurers fulfilling their obligations. The Company began reinsuring risks at this level during 2001 (2002 for RiverSource Life of NY) for term life insurance and 2002 (2003 for RiverSource Life of NY) for individual fixed and variable universal life insurance. -

Secondary Guarantee Universal Life: Practical Considerations

Secondary Guarantee Universal Life: Practical Considerations MILLIMAN INC . March 2007 Prepared by: Keith Dall Donna Megregian Rob Stone Executive summary Secondary guarantee universal life insurance (SGUL) has been a major product in the U.S. permanent life insurance market. This report discusses the history of SGUL products and the reserving mechanisms underlying product mechanics in each of several reserving eras. Pricing results are presented for sample protection and accumulation life products with a secondary guarantee. Stochastic results are presented for protection and accumulation versions of traditional fixed SGUL products along with accumulation product results for indexed and variable SGUL products. The potential for applying risk management techniques on SGUL products is also discussed, and sample Greeks are calculated and presented for a variable SGUL product. Principles-based reserving and its impact on SGUL products are reviewed; sample pricing results demonstrate reduced capital strain for two traditional fixed products under principles-based reserves. The report concludes with a discussion on pricing an SGUL product, assuming future surplus relief, including an AXXX securitization example that outlines the potential for improved profitability for an SGUL product coupled with a securitization solution. Acknowledgements This report has been prepared for clients and potential clients of Milliman. The primary authors are: Keith Dall Donna Megregian Rob Stone The authors would like to thank the following Milliman consultants for their contributions: Sam Nandi Karen Rudolph Steve Schreiber Eric Schwartz Dean Willman Wendy Yu Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS 2 2. OVERVIEW OF THE SGUL MARKET 3 3. PROTECTION-ORIENTED, TRADITIONAL FIXED SGUL 8 4. ACCUMULATION-ORIENTED, TRADITIONAL FIXED SGUL 12 5. -

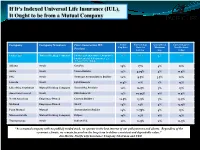

If It's Indexed Universal Life Insurance, It Ought to Be from A

If It’s Indexed Universal Life Insurance (IUL), It Ought to be from a Mutual Company IUL clients depend on the life insurance company to continue to offer competitive indexed growth cap rates over the life of their policy. Mutual companies are owned by their policyowners—not outside shareholders—and can make financial decisions without the pressure of providing a dividend to their stockholders. As a mutual holding company, Pacific Life Insurance Company answers to policyowners, not shareholders. As of October 1, 2013 , policyowners who purchased our very first IUL product in September 2005 still enjoy the same indexed growth cap (12%) as they did the day they bought the policy. Most other companies cannot make that claim (see the table below): Company Company Structure First-Generation IUL Initial Current Cap Guaranteed Current Cap for Cap Rate1 Rate for Minimum New Products Product Inforce2 Cap Today3 Pacific Life Mutual Holding Company Pacific Life Insurance Company’s 12% 12% 3% 12% Pacific Indexed Performer LT (Policy Form No. P11PIP) Allianz Stock GenDex 19% 17% 4% 12% Aviva Stock Vision Builder 12% 9.75% 4% 11.5% ING Stock Strategic Accumulation Builder 10% 9.5% 3.5% 12% Lincoln Stock Life Elements 11.5% 11% 1% 13% Life of the Southwest Mutual Holding Company SecurePlus Provider 12% 10.5% 3% 13% American General Stock Elite Index UL 12% 10.75% 0% 11.5% North American Employee-Owned Custom Builder 1 12.5% 13.5% 3% 13.5% Midland Employee-Owned XL-CV 14% 14% 4% 14.5% Penn Mutual Mutual Accumulation Builder 14% 11.75% 4% 13% Minnesota Life Mutual Holding Company Eclipse 17% 13% 0% 13% Transamerica Stock Indexed UL 21% 12.5% 0% 12.5% “As a mutual company with no publicly traded stock, we operate in the best interest of our policyowners and clients.