Game Narrative Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spiritfarer.7Z Spiritfarer.7Z

Spiritfarer.7z Spiritfarer.7z 1 / 2 Spiritfarer [NSZ], 2020-08-19 02:51:02, 1.45 GB. The Legend of Zelda Links ... 01 NS 1.8.2 全能模拟器 [密码 UFO] 12.25.7z, 2019-12-28 03:14:11, 261.61 MB.. Jan 16, 2021 — Really addicted to Spiritfarer lately. Anonymous 5 months ago No. 122523. I just beat Astral Chain on easy mode, and now I'm doing all the ... Project Wingman Walkthrough and Guide Spiritfarer Walkthrough and Guide ... Are in 7zip format stories for Langrisser 2, and langrisser iv walkthrough even .... ... N4, nt, uE, 20, 1S, Bd, WJ, 6l, 2Y, sC, pG, XX, Mr, ES, ds, 8Q, AC, 1B, di, nN, eE, 7z, kC, 2B, 3V, eH, 1w, 41, 8a, ... Spiritfarer has reached over 500k copies sold.. ... Battletoads, Wasteland 3, CK3, Tell Me Why, Spiritfarer, New Super Lucky's Tale ... make sure to get WinRAR or 7Zip to unpack existing RSN files to do this.. ... tony hawk's pro skater 1 + 2 podcast #411: blast for 15 minutes – spiritfarer, ... Step 1: right-click on your rar, zip, or 7z file in your downloads folder (you can .... Mar 20, 2021 — Step 2: Extract it using an archive manager such as WinRAR or 7Zip. You will then have two files, DS4Windows and DS4Update. spiritfarer spiritfarer, spiritfarer recipes, spiritfarer achievements, spiritfarer switch, spiritfarer release date, spiritfarer review, spiritfarer game, spiritfarer wiki, spiritfarer spirits, spiritfarer update, spiritfarer gameplay, spiritfarer gwen, spiritfarer xp potion, spiritfarer steam, spiritfarer guide, spiritfarer metacritic Game Info Game Mission - Impossible File Name Mission - Impossible.7z File ... Updates Spiritfarer Walkthrough and Guide Shining Beyond Walkthrough and ... -

Balasko-Mastersreport-2020

The Report Committee for Alexander Balasko Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: An Untitled Goose by Any Other Name: A Critical Theorization of the Indie Game Genre APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: _____________________________________ James Buhler _____________________________________ Bryan Parkhurst An Untitled Goose by Any Other Name: A Critical Theorization of the Indie Game Genre by Alexander Balasko Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 An Untitled Goose by Any Other Name: A Critical Theorization of the Indie Game Genre Alexander Balasko, M.Music The University of Texas at Austin, 2020 Supervisor: James Buhler As the field of ludomusicology has grown increasingly mainstream within music studies, a methodological trend has emerged in discussions of genre that privileges the formal attributes of game sound while giving relatively little attention to aspects of its production. The problems with this methodological bent become apparent when attempting to discuss the independent (“indie”) game genre, since, from 2010-2020 the indie game genre underwent a number of significant changes in aesthetic trends, many of which seem incoherent with one another. As such, the indie genre has received relatively little attention within the ludomusicological literature despite its enormous impact on broader gaming culture. By analyzing the growth of chiptune aesthetics beginning in 2008 and the subsequent fall from popularity towards 2020, this paper considers how a satisfying understanding of the indie game genre can be ascertained through its material cultures, rather than its aesthetics or gameplay. -

Player-Avatar Relationship Beyond the Fourth Wall

Journal of Games Criticism Volume 4, Issue 1 “Together They Are Twofold”: Player-Avatar Relationship Beyond the Fourth Wall Agata Waszkiewicz Abstract Although breaking the fourth wall is one of the most common ways to achieve com- ic relief in films and TV series, some argue for its meaningful function as a technique enhancing the audience’s informed experience of the text. While it seems obvious what “breaking the fourth wall” means in the theater context (Stevenson, 1995), in video game studies there seems to be a substantial confusion surrounding this term with multiple cases of varied use. A common voice seems to be the one negating not only the existence of the fourth wall in specific video games (Conway, 2010) but the sole possi- bility of its existence in the whole medium (Jørgensen, 2013). On the other hand, those who speak in favor of it seem to use this term very broadly (Kubiński, 2016). By reaching back to literary and theater theory, in this paper I aim to organize and clarify the various terms connected to metafiction, placing a particular emphasis on different definitions of the “fourth wall”. Furthermore, I will distinguish between fiction-aware characters who recognize their fictionality without the awareness of the player and the two types of game-player communication through the wall: one-directional and the twofold play of the player. A character in World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004–2017) stares blankly at the empty space in front of them and proclaims that their “inventory is full” when there is no one around to hear them. -

The Impact of Real Life Data on Player Experience

The impact of real life data on player experience A case study on the pervasiveness of encountering real life data in the videogame ‘OneShot’. Bart Wellens Snr. 2017791 Master Thesis Communication and Information Sciences Track: New Media Design School of Humanities and Digital Sciences Tilburg University, Tilburg Supervisor: Amalía Kallergi Second reader: Monique Pollman Augustus 2018 Word count: 15442 REAL LIFE DATA AND PLAYER EXPERIENCE Abstract This research focusses on the impact of real life data on the player experience in videogames. Including real life data in videogames is blurring the boundaries between the game world and the real world, these games are called pervasive. Pervasive games are often driven by technological advances. This often causes research to be interested in the functional aspects of user experiences, instead of the emotional gameplay experiences (Montola, 2011, p. 10). This means there is a gap in research literature on how players actually experience this blurring of boundaries. Building on theories of designed experience, fourth wall breaks, player experience and personalisation, this thesis conducts a case study, incorporating real life data from the game OneShot. A three-part method was used. First, qualitative content analysis using hybrid coding method over seven reviews (five official platform reviews, two user comments), provided general themes about player experience and encountering real life data. Second, auto-ethnographic research was conducted to gain better understanding of the themes and to give my expert opinion on the subject. Lastly, a video analysis capturing direct responses to encountering real life data was conducted. Seven themes emerged, which were used as a thread throughout the auto-ethnographic research and video analysis. -

This Is Your Last Warning Before You Click The

Define your needs Let’s say we need: • Funding to cover remaining developer costs • Marketing • Community building • Distribution to consoles and PC platforms • QA • Localization • General guidance Define your development timeline What work have you put into the project to date? Where are you today? What features are done? • We’re about 40% done with the game. Current investment is $10K + 32% royalties promised (post-agreements). This means I’ve brought people on who work for royalties and I’ve promised that they will (collectively) get 32% of the sale of each game after distribution and publishing cuts are taken. • We’ve implemented 2 of our 3 core gameplay mechanics, with 1 of them being fully polished. • Half of our characters, enemies, bosses and environments are implemented. What work is left to do to release the game (define what is R&D vs. known development)? • Implement the last gameplay mechanic (R&D) and polish the last 2 • Focus a significant amount of time on UX and tutorials • Wrap up our character art • Implement 3 of the 6 bosses • Implement 10 of the 22 minion enemies • Create 10 more environment locations, out of 20 total Define your market What platform(s) do you want your game to ship on? We want to be on PC and Consoles. For PC, we’re looking at Steam as well as other platforms like Epic Games Store, GOG, and Humble Bundle. For consoles, we haven’t begun development on any platforms, but we have been given dev access to Xbox and PlayStation. We’re still trying to get onto Switch but haven’t made much inroads. -

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

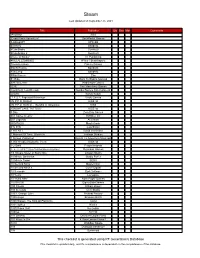

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Oneshot Download Blackbox

OneShot Download Blackbox Download ->>> http://bit.ly/2QR9spG About This Game www.oneshot-game.com A surreal puzzle adventure game with unique mechanics / capabilities. You are to guide a child through a mysterious world on a mission to restore its long-dead sun. ...Of course, things are never that simple. The world knows you exist. The consequences are real. Saving the world may be impossible. 1 / 15 You only have one shot. FEATURES Gameplay mechanics that go beyond the game window. A haunting original soundtrack and artwork designed to match. A unique relationship between a game and its player. A lingering feeling that you're not getting the full story unless you know where to look. CONTENT WARNING Although OneShot is not a horror game in the traditional sense, parts the game may induce some paranoia. Please proceed with caution. CLOSING THE GAME WINDOW Do not worry, it is safe to do so. It only saves your progress. 2 / 15 Title: OneShot Genre: Adventure, Casual, Indie Developer: Little Cat Feet Publisher: Degica Release Date: 8 Dec, 2016 7ad7b8b382 English,Japanese,French,Korean,Simplified Chinese 3 / 15 4 / 15 5 / 15 6 / 15 oneshot pickleball. oneshot memes. oneshot kelvin. oneshot reddit. oneshot maize. oneshot on little cat feet. oneshot story. oneshot lightbulb. oneshot network. oneshot meaning. one shot kayn build. oneshot jhin build. oneshot quiz. oneshot kernel. oneshot quinn. oneshot official art. oneshot length. oneshot karthus build. one shot prompts. oneshot niko fanart. oneshot outsider. oneshot light puzzle. one shot kill. oneshot fortnite. oneshot que significa. oneshot merch. oneshot photography. oneshot original version. -

The World Machine. Self-Reflexive Worldbuilding in Oneshot

The World Machine Self-Reflexive Worldbuilding in OneShot Theresa Krampe Abstract Worldbuilding in video games is typically associated with the cre- ation of immersive virtual environments. In the independent puzzle adventure OneShot (Little Cat Feet 2016), however, worldbuilding becomes the game’s central theme in a highly self-referential manner. OneShot presents a multilay- ered universe in which not only characters and players but the game’s very code seem to move freely between ontological levels. Drawing attention to the aes- thetics and mechanics of worldbuilding and deconstructing the architecture of its own game world, OneShot invites reflection on the relation between fiction and computation; the virtual and the actual. Keywords Worldbuilding, video games, self-reflexivity, metalepsis, immersion Introduction Imaginative worldbuilding, researchers from the cognitive sciences to transmedia nar- ratology agree, is an activity that comes naturally to us as human beings and helps us to make sense of the ‘real world’ (see Holland 2009; Wolf 2012; Ryan 2015a). We engage with the fictional worlds presented to us in various media or construct our own imaginary worlds because we take pleasure in the experience of being transported to a different reality. With the rise of cognitive narratology, engagement with fictional worlds has also been linked to empathic growth, attitude change, and improved theory of mind (Mar and Oatley 2008; Kidd and Castano 2013; Nünning 2014; Fitzgerald and Green 2017). While an increase in the popularity of worldbuilding can currently be observed across media (see Wolf 2012), video games seem to find themselves in a privileged position when it comes to creating elaborate simulated environments that the player can enter. -

Universidade Federal De Pernambuco Potencial Empático

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco Centro de Artes e Comunicação | Departamento de Design Programa de Pós-Graduação em Design _ Potencial Empático Visual em Personagens Pixel Art: um Referencial de Design para Jogos Digitais Rowan Henrique Sarmento Silveira Recife, Junho de 2017 Universidade Federal de Pernambuco Centro de Artes e Comunicação | Departamento de Design Programa de Pós-Graduação em Design Potencial Empático Visual em Personagens Pixel Art: um Referencial de Design para Jogos Digitais Dissertação apresentada à banca de Pós-Graduação em Design da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco como requisito para a obtenção do grau de Mestre. Área de Concentração: Design de Artefatos Digitais. Rowan Henrique Sarmento Silveira Orientação | Prof. Dr. André M. M. Neves Recife, Junho de 2017 Catalogação na fonte Bibliotecária Nathália Sena, CRB4-1719 S587p Silveira, Rowan Henrique Sarmento Potencial empático visual em personagens Pixel Art: um referencial de design para jogos digitais / Rowan Henrique Sarmento Silveira. – Recife, 2017. 166 f.: il. Orientador: André Menezes Marques das Neves. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Centro de Artes e Comunicação. Design, 2017. Inclui referências. 1. Personagens de vídeo game. 2. Pixel art. 3. Potencial empático. 4. Representação gráfica I. Neves, André Menezes Marques das (Orientador). II. Título. 794.8 CDD (22.ed.) UFPE (CAC 2017- 202) UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM DESIGN PARECER DA COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA DE DEFESA DE DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO ACADÊMICO DE Rowan Henrique Sarmento Silveira “Potencial Empático Visual em Personagens Pixel Art: um Referencial de Design para Jogos Digitais.” ÁREA DE CONCENTRAÇÃO: Planejamento e Contextualização de Artefatos. A comissão examinadora, composta pelos professores abaixo, sob a presidência do primeiro, considera o(a) candidato(a) Rowan Henrique Sarmento Silveira APROVADO. -

A Feminist Content Analysis of Female Video Game Characters, and Interviews with Female Gamers

“Pretty Good for a Girl”: A Feminist Content Analysis of Female Video Game Characters, and Interviews with Female Gamers Cardiff University School of Journalism, Media, and Culture Master of Philosophy (Journalism Studies) 2018 Elizabeth Munday Abstract Feminist media scholars have long sought to understand the representations of women in the media, in which women are consistently depicted as secondary to men, which they have used to highlight issues of gender relations. My research involved the analysis of representations of female characters in games and explored how female gamers make sense of them, providing a more in-depth look at women in the media, whilst also addressing issues of gender such as leisure time. The gendering of leisure is important as it provides a wider basis for my more nuanced arguments about video games and those who play them. Throughout my research I endeavoured to study not only how women are represented in video games, but also the experiences of female gamers and how they continue to interact with the gaming community. Drawing widely from existing feminist media research, I studied the common representations of women in video games, and what female gamers thought of them. I also researched their experiences as female gamers within the gaming community – how they had been treated as “gamers”, but also how they continued to engage and interact with the gaming community. In order to gather this information, I utilised Content Analysis to gather and analyse game content through further Visual Analysis. This provided me with a range of insights into common patterns in the representations of women across a wide range of currently popular games, such as the role of healer.