Airbnb NYCLU Testimony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPIC V. ICE Complaint (Palantir) V0.99

Case 1:17-cv-02684 Document 1 Filed 12/15/17 Page 1 of 11 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION CENTER 1718 Connecticut Avenue, NW Suite 200 Washington, DC 20009, Plaintiff, v. Civ. Action No. 17-2684 U.S. IMMIGRATION AND CUSTOMS ENFORCEMENT 500 12th Street SW Washington, DC 20536, Defendant. COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE RELIEF 1. This is an action under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), 5 U.S.C. § 552, for injunctive and other appropriate relief, seeking the release of agency records requested by the Plaintiff Electronic Privacy Information Center (“EPIC”) from Defendant Immigration and Customs Enforcement (“ICE”), a component of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”). 2. EPIC challenges ICE’s failure to make a timely response to EPIC’s Freedom of Information Act request (“EPIC’s FOIA Request”) for records about ICE’s contracts and other information related to the FALCON systems and the Investigative Case Management (“ICM”) system. 1 Case 1:17-cv-02684 Document 1 Filed 12/15/17 Page 2 of 11 Jurisdiction and Venue 3. This Court has subject matter jurisdiction over this action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1331 and 5 U.S.C. §§ 552, (a)(6)(E)(iii), (a)(4)(B). This Court has personal jurisdiction over Defendant ICE. 4. Venue is proper in this district under 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B). Parties 5. Plaintiff EPIC is a nonprofit organization, incorporated in Washington, DC, established in 1994 to focus public attention on emerging privacy and civil liberties issues. -

PETER THIEL Palantir Technologies; Thiel Foundation; Founders Fund; Paypal Co-Founder

Program on SCIENCE & DEMOCRACY Science, Technology & Society LECTURE SERIES 2015 HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL HARVARD UNIVERSITY PETER THIEL Palantir Technologies; Thiel Foundation; Founders Fund; PayPal co-founder BACK TO THE FUTURE Will we create enough new technology to sustain our society? WITH PANELISTS WEDNESDAY Antoine Picon Travelstead Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Design March 25, 2015 Margo Seltzer Harvard College Professor, School of Engineering and 5:00-7:00pm Applied Sciences Science Center Samuel Moyn Professor of Law and History, Harvard Law School Lecture Hall C 1 Oxford Street MODERATED BY Sheila Jasanoff Harvard University Pforzheimer Professor of Science and Technology Studies CO-SPONSORED BY Program on Harvard University Harvard School of Harvard University Center for the Engineering and Graduate School Science, Technology & Society Environment Applied Sciences of Design HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL HARVARD UNIVERSITY http://sts.hks.harvard.edu/ Program on SCIENCE & DEMOCRACY Science, Technology & Society LECTURE SERIES 2015 HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL HARVARD UNIVERSITY Peter Thiel is an entrepreneur and investor. He started PayPal in 1998, led it as CEO, and took it public in 2002, defining a new era of fast and secure online commerce. In 2004 he made the first outside investment in Facebook, where he serves as a director. The same year he launched Palantir Technologies, a software company that harnesses computers to empower human analysts in fields like national security and global finance. He has provided early funding for LinkedIn, Yelp, and dozens of successful technology startups, many run by former colleagues who have been dubbed the “PayPal Mafia.” He is a partner at Founders Fund, a Silicon Valley venture capital firm that has funded companies like SpaceX and Airbnb. -

Investments in the Fourth Industrial Revolution

THE NATIONAL SECURITY INNOVATION BASE: INVESTMENTS IN THE FOURTH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION Foreword by Chris Taylor, CEO COMPANIES INCLUDED AASKI Technology Inc. ERAPSCO Red River Inc. Abbott Laboratories (ABT) Esri RELX Group (RELX) Accenture PLC (ACN) Falcon Fuels Inc. Research Triangle Institute ActioNet Inc. FCN Inc. Rockwell Collins Inc. (COL) ADS Tactical Inc. FEi Systems Safran SA (SAF) AECOM (ACM) Fluor Corp. (FLR) SAIC Corp. (SAIC) Aerojet Rocketdyne Inc. (AJRD) Four Points Technology LLC Sanofi Pasteur (SNY) AeroVironment Inc. (AVAV) Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center SAP SE (SAP) AI Solutions Inc. Galois Inc. Savannah River AKESOgen Inc. General Atomics Inc. Science Systems and Applications Inc. Alion Science & Technology Corp. General Dynamics Corp. (GD) Serco Inc. American Type Culture Collection GlaxoSmithKline PLC (GSK) SGT Inc. Analytic Services Inc. Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Corp. Siemens Corp. (SIE) Analytical Mechanics Associates Inc. Harris Corp. Sierra Lobo Inc. Aptima Inc. Hewlett-Packard Co. (HPQ) Sigma Space Corp. Archer Western Aviation Partners Honeywell International Inc. (HON) Smartronix Inc. Arctic Slope Regional Corp. HRL Laboratories Soar Technology Inc. Astrazeneca PLC (AZN) Huntington Ingalls (HII) Sprint Corp. (S) AT&T Inc. (T) HydroGeoLogic Inc. Technologies Forensic AURA International Business Machines Corp. (IBM) Teledyne Technologies Inc. BAE Systems Inc. (BA) immixGroup Inc. Textron (TXT) Balfour Beatty PLC (BBY) InfoReliance Corp. The Shaw Group (CBI) Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. Insight Public Sector Inc. (NSIT) The Walsh Group Co. Battelle Memorial Institute Intelligent Automation Inc. Thermo Fisher Scientific (TMO) Bell-Boeing JP Intelligent Software Solutions Inc. Thomson Reuters Corp. (TRI) Boeing Co. (BA) Iridium Communications Inc. (IRDM) Torch Technologies Inc. Booz Allen Hamilton Inc. -

V4.4 Final Palantir NT4T PI Report Corrected

September 2020 September 2020 All roads lead to Palantir: A review of how the data analytics company has embedded itself throughout the UK privacyinternational.org notechfortyrants.org All Roads Lead to Palantir: A review of how the data analytics company has embedded itself throughout the UK Authors This report was compiled by No Tech For Tyrants, a student-led, UK-based organisation working to sever the links between higher education, violent technology, and hostile immigration environments, in collaboration with Privacy International. Find out more about No Tech For Tyrants: notechfortyrants.org Researchers: Mallika Balakrishnan Niyousha Bastani Matt Mahmoudi Quito Tsui Jacob Zionts 1 All Roads Lead to Palantir: A review of how the data analytics company has embedded itself throughout the UK ABOUT PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL Governments and corporations are using technology to exploit us. Their abuses of power threaten our freedoms and the very things that make us human. That’s why Privacy International campaigns for the progress we all deserve. We’re here to protect democracy, defend people’s dignity, and demand accountability from the powerful institutions who breach public trust. After all, privacy is precious to every one of us, whether you’re seeking asylum, fighting corruption, or searching for health advice. So, join our global movement today and fight for what really matters: our freedom to be human. Open access. Some rights reserved. No Tech for Tryants and Privacy International wants to encourage the circulation of its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. We has an open access policy which enables anyone to access its content online without charge. -

IPA, Palantir in Pact to Boost Qatar's Digital Transformation

Zoho partners with BNI to digitally enable local businesses in GCC PAGE 9 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 22, 2020 28,350.71 9,965.03 40707.31 1,926.70 +41.92 PTS -50.49 PTS +162.94 PTS GOLD +0.59 % US officials more optimistic on DOW QE SENSEX stimulus, timing unclear PAGE 10 PRICE PERCENTAGE PRICE PERCENTAGE 25.17 BRENT 41.77 -3.22% WTI 40.10 -3.84% SILVER +0.74% QIB closes $750 million 5-year Sukuk QNA DOHA QATAR Islamic Bank (QIB) has successfully closed a $750 million five-year Sukuk with a profit rate of 1.95 percent per annum, which is equivalent to a credit spread of 155 basis point (bps) over the 5-year Mid Swap Rate. Officials of Investment Promotion Agency Qatar and Palantir Technologies during a meeting to discuss best practices to accelerate Qatar’s big-data transformation. The transaction was ex- ecuted under QIB’s $4 bil- lion Trust Certificate Issuance Programme which is listed on Euronext Dublin. The profit rate achieved is the lowest IPA, Palantir in pact to boost ever paid by QIB on their fixed $4 billion rate Sukuk issuances. This is ● The transaction was QIB’s second public issuance in 2020, having issued the executed under QIB’s $4 first ever Formosa Sukuk ear- billion Trust Certificate Issu- Qatar’s digital transformation lier this year. ance Programme which is The success of this trans- listed on Euronext Dublin TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK unique infrastructure and logistical action came on the back of a ● This is QIB’s second DOHA challenges set out in the Qatar Nation- marketing strategy aimed at al Vision 2030. -

16-784 C Original Filed

Case 1:16-cv-00784-MBH Document 1 Filed 06/30/16 PageReceipt 1 number of 84 9998-3405680 ORIGINAL UNITED STATES COURT OF FEDERAL CLAIMS BID PROTEST PALANTIR TECHNOLOGIES INC., and PALANTIR USG, INC. Plaintiffs, Case No. ______16-784 C -vs.- UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, FILED Defendant. JUNE 30, 2016 U.S. COURT OF FEDERAL CLAIMS COMPLAINT Hamish P.M. Hume Stacey Grigsby Jon R. Knight BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER LLP 5301 Wisconsin Ave. NW Washington, DC 20015 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (202) 237-2727 (Telephone) (202) 237-6131 (Fax) Counsel for Plaintiff Palantir Case 1:16-cv-00784-MBH Document 1 Filed 06/30/16 Page 2 of 84 TABLE OF CONTENTS NATURE OF THE CASE .............................................................................................................. 1 PARTIES ...................................................................................................................................... 12 JURISDICTION ........................................................................................................................... 13 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................... 13 A. The Law Requires The Army To Procure Commercial Items To The Maximum Extent Practicable To Satisfy Its Requirements. ................................................... 13 B. The Army Admits It Has A Critical Requirement For A Data Management Platform That It Has Been Unable To Satisfy Despite Fifteen Years Of Effort And Billions Of Dollars -

Spooky Business: Corporate Espionage Against Nonprofit Organizations

Spooky Business: Corporate Espionage Against Nonprofit Organizations By Gary Ruskin Essential Information P.O Box 19405 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 387-8030 November 20, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 5 The brave new world of corporate espionage 5 The rise of corporate espionage against nonprofit organizations 6 NARRATIVES OF CORPORATE ESPIONAGE 9 Beckett Brown International vs. many nonprofit groups 9 The Center for Food Safety, Friends of the Earth and GE Food Alert 13 U.S. Public Interest Research Group, Friends of the Earth, National Environmental Trust/GE Food Alert, Center for Food Safety, Environmental Media Services, Environmental Working Group, Institute for Global Communications, Pesticide Action Network. 15 Fenton Communications 15 Greenpeace, CLEAN and the Lake Charles Project 16 North Valley Coalition 17 Nursing home activists 17 Mary Lou Sapone and the Brady Campaign 17 US Chamber of Commerce/HBGary Federal/Hunton & Williams vs. U.S. Chamber Watch/Public Citizen/Public Campaign/MoveOn.org/Velvet Revolution/Center for American Progress/Tides Foundation/Justice Through Music/Move to Amend/Ruckus Society 18 HBGary Federal/Hunton & Williams/Bank of America vs. WikiLeaks 21 Chevron/Kroll in Ecuador 22 Walmart vs. Up Against the Wal 23 Électricité de France vs. Greenpeace 23 E.ON/Scottish Resources Group/Scottish Power/Vericola/Rebecca Todd vs. the Camp for Climate Action 25 Burger King and Diplomatic Tactical Services vs. the Coalition of Immokalee Workers 26 The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association and others vs. James Love/Knowledge Ecology International 26 Feld Entertainment vs. PETA, PAWS and other animal protection groups 27 BAE vs. -

Who's Behind ICE: Tech and Data Companies Fueling Deportations

Who’s Behind ICE? The Tech Companies Fueling Deportations Tech is transforming immigration enforcement. As advocates have known for some time, the immigration and criminal justice systems have powerful allies in Silicon Valley and Congress, with technology companies playing an increasingly central role in facilitating the expansion and acceleration of arrests, detentions, and deportations. What is less known outside of Silicon Valley is the long history of the technology industry’s “revolving door” relationship with federal agencies, how the technology industry and its products and services are now actually circumventing city- and state-level protections for vulnerable communities, and what we can do to expose and hold these actors accountable. Mijente, the National Immigration Project, and the Immigrant Defense Project — immigration and Latinx-focused organizations working at the intersection of new technology, policing, and immigration — commissioned Empower LLC to undertake critical research about the multi-layered technology infrastructure behind the accelerated and expansive immigration enforcement we’re seeing today, and the companies that are behind it. The report opens a window into the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) plans for immigration policing through a scheme of tech and database policing, the mass scale and scope of the tech-based systems, the contracts that support it, and the connections between Washington, D.C., and Silicon Valley. It surveys and investigates the key contracts that technology companies have with DHS, particularly within Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and their success in signing new contracts through intensive and expensive lobbying. Targeting Immigrants is Big Business Immigrant communities and overpoliced communities now face unprecedented levels of surveillance, detention and deportation under President Trump, Attorney General Jeff Sessions, DHS, and its sub-agency ICE. -

Peter Thiel Joins Abcellera's Board of Directors

2215 Yukon St . Vancouver, BC Canada, V5Y 0A 1 T 1. 604.559.90 05 abcellera.com NEWS RELEASE Peter Thiel Joins AbCellera’s Board of Directors 11/19/2020 VANCOUVER, British Columbia, November 19, 2020 – AbCellera, a technology company that searches, decodes, and analyzes natural immune systems to nd antibodies that can be developed to prevent and treat disease, today announced the appointment of Peter Thiel to its Board of Directors. “Peter has been a valued AbCellera investor and brings deep experience in scaling global technology companies,” said Carl Hansen, Ph.D., CEO of AbCellera. “We share his optimistic vision for the future, faith in technological progress, and long-term view on company building. We’re excited to have him join our board and look forward to working with him over the coming years.” Mr. Thiel is a technology entrepreneur, investor, and author. He was a co-founder and CEO of PayPal, a company that he took public before it was acquired by eBay for $1.5 billion in 2002. Mr. Thiel subsequently co-founded Palantir Technologies in 2004, where he continues to serve as Chairman. As a technology investor, Mr. Thiel made the rst outside investment in Facebook, where he has served as a director since 2005, and provided early funding for LinkedIn, Yelp, and dozens of technology companies. He is a partner at Founders Fund, a Silicon Valley venture capital rm that has funded companies including SpaceX and Airbnb. “AbCellera is executing a long-term plan to make biotech move faster. I am proud to help them as they raise our expectations of what’s possible,” said Mr. -

Govcon5 Program Guide.Pdf 665.13 Kib Application/Pdf

AGENDA OPTIONAL PRE-CONFERENCE INTRODUCTION TO PALANTIR 8:30-9:30 PALANTIR 101 New to Palantir? This special pre-conference session will SALON cover the basics. Additionally, please see page 6 for the on- site training schedule. MAIN SESSIONS 10:00 WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION SALON Dr. Alex Karp, CEO, Palantir 10:10 HUNTING ADVANCED PERSISTENT THREATS IN CYBERSPACE SALON Rafal Rohozinski, Principal and CEO, SecDev Group Nart Villeneuve, Chief Security Officer, SecDev Group 10:50 USING PALANTIR TO ANALYZE IRANIAN GLOBAL INFLUENCE SALON Doug Philippone, Palantir 11:30 SIGINT & PALANTIR: THE FUSION OF TARGET DATA, REPORTING AND TRAFFIC SALON Trae Stephens, Forward Deployed Engineer, Palantir 12:00-13:00 LUNCH & DEMOS FOYER 13:15 USING PALANTIR WITH OPEN SOURCE DATA: FINDING AND PREVENTING FRAUD IN STIMULUS SPENDING SALON Douglas R. Hassebrock, Assistant Director, Investigations, Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board Alex Fishman, Forward Deployed Engineer, Palantir 13:45 WHAT’S NEW IN PALANTIR GOVERNMENT 2.4 SALON Bob McGrew, Director of Engineering, Palantir 14:15 ATTACK THE NETWORK SALON Bruce Parkman, CEO, NEK Advanced Securities Group 14:45-15:00 COFFEE BREAK FOYER 4 AGENDA CHOOSE YOUR NEXT SESSION - PART ONE 15:00-15:40 CYBER SECURITY ANALYSIS IN PALANTIR SALON Geoffrey Stowe, Forward Deployed Engineer, Palantir 15:00-15:40 PROTECTING PRIVACY AND CIVIL LIBERTIES WITH COMMERCIALLY AVAILABLE TECHNOLOGY PLAZA Bryan Cunningham, Senior Counsel and Advisory Board Member, Palantir 15:00-15:40 MANAGING A COMPLEX DISTRIBUTED SYSTEM: MADE -

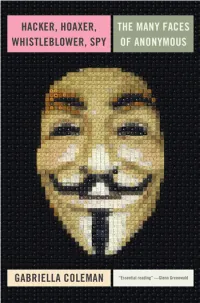

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future. -

Human and Machine Intelligence in the Petabyte Age

Programming Insight: Human and Machine Intelligence in the Petabyte Age by Osita Anders Udekwu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor David Bates, Chair Professor Charis Thompson Professor Michael Wintroub Summer 2017 Abstract Programming Insight: Human and Machine Intelligence in the Petabyte Age by Osita Anders Udekwu Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric University of California, Berkeley Professor David Bates, Chair This dissertation, entitled Programming Insight: Human and Machine Intelligence in the Petabyte Age, explores the ideal of “intelligent” organizations through a close reading of a data fusion and analysis environment for government and enterprise by Palantir Technologies. Using approaches from science and technology studies, human-computer interaction, and new media theory, the project links understandings of computation and interactivity with emerging infrastructures for knowledge practices. My work examines the relationships between epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics for a digital platform that works in support of organizations that, in the words of former NSA director Michael Hayden, “kill people based on metadata.” My dissertation examines the digital and human processes that purport to transform digital traces into knowledge and insight in domains from finance to counter-terror. Commonly cast as a generic surveillance technology, I argue that