Reading Dialectically: the Political Play of Form, Contingency, and Subjectivity in Rabindranath Tagore and C.L.R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rabindranath's Nationalist Thought

5DELQGUDQDWK¶V1Dtionalist T hought: A Retrospect* Narasingha P. Sil** Abstract : 7DJRUH¶VDQWL-absolutist and anti-statist stand is predicated primarily on his vision of global peace and concord²a world of different peoples and cultures united by amity and humanity. While this grand vision of a brave new world is laudable, it is, nevertheless, constructed on misunderstanding and misreading of history and of the role of the nation state in the West since its rise sometime during the late medieval and early modern times. Tagore views state as an artificial mechanism, indeed a machine thDWWKULYHVRQFRHUFLRQFRQIOLFWDQGWHUURUE\VXEYHUWLQJSHRSOH¶VIUHHGRPDQG culture. This paper seeks to argue that the state also played historically a significant role in enhancing and enriching culture and civilization. His view of an ideal human society is sublime, but by the same token, somewhat ahistorical and anti-modern., K eywords: Anarchism, Babu, Bengal Renaissance, deshaprem [patriotism], bishwajiban [universal life], Gessellschaft, Gemeinschaft, jatiyatabad [nationalism], rastra [state], romantic, samaj [society], swadeshi [indigenous] * $QHDUOLHUVKRUWHUYHUVLRQRIWKLVSDSHUWLWOHG³1DWLRQDOLVP¶V8JO\)DFH7DJRUH¶V7DNH5HYLVLWHG´ZDVSUHVHQWHGWR the Social Science Seminar, Western Oregon University on January 27, 2010 and I thank its convener Professor Eliot Dickinson of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration for inviting me. All citations in Bengali appear in my translation unless stated otherwise. BE stands for Bengali Era that follows the -

Government Advertising As an Indicator of Media Bias in India

Sciences Po Paris Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India by Prateek Sibal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master in Public Policy under the guidance of Prof. Julia Cage Department of Economics May 2018 Declaration of Authorship I, Prateek Sibal, declare that this thesis titled, 'Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India' and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that: This work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for Masters in Public Policy at Sciences Po, Paris. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Signed: Date: iii Abstract by Prateek Sibal School of Public Affairs Sciences Po Paris Freedom of the press is inextricably linked to the economics of news media busi- ness. Many media organizations rely on advertisements as their main source of revenue, making them vulnerable to interference from advertisers. In India, the Government is a major advertiser in newspapers. Interviews with journalists sug- gest that governments in India actively interfere in working of the press, through both economic blackmail and misuse of regulation. However, it is difficult to gauge the media bias that results due to government pressure. This paper determines a newspaper's bias based on the change in advertising spend share per newspa- per before and after 2014 general election. -

SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY 244 Theatrelog Issue 29/30 Jun 2001 Acknowledgements

2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 7 ‘My kind of theatre is for the people’ KUMAR ROY 37 ‘And through the poetry we found a new direction’ SHYAMAL GHO S H 59 Minority Culture, Universal Voice RUDRAPRA S AD SEN G UPTA 81 ‘A different kind of confidence and strength’ Editor AS IT MU K HERJEE Anjum Katyal Editorial Consultant Samik Bandyopadhyay 99 Assistants Falling in Love with Theatre Paramita Banerjee ARUN MU K HERJEE Sumita Banerjee Sudeshna Banerjee Sunandini Banerjee 109 Padmini Ray Chaudhury ‘Your own language, your own style’ Vikram Iyengar BI B HA S H CHA K RA B ORTY Design Sunandini Banerjee 149 Photograph used on cover © Nemai Ghosh ‘That tiny cube of space’ MANOJ MITRA 175 ‘A theatre idiom of my own’ AS IT BO S E 197 The Totality of Theatre NIL K ANTHA SEN G UPTA 223 Conversations Published by Naveen Kishore 232 for The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Appendix I 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 Notes on Classic Playtexts Printed at Laurens & Co. 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 234 Appendix II Notes on major Bengali Productions 1944 –-2000 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY 244 Theatrelog Issue 29/30 Jun 2001 Acknowledgements Most of the material collected for documentation in this issue of STQ, had already been gathered when work for STQ 27/28 was in progress. We would like to acknowledge with deep gratitude the cooperation we have received from all the theatre directors featured in this issue. We would especially like to thank Shyamal Ghosh and Nilkantha Sengupta for providing a very interesting and rare set of photographs; Mohit Chattopadhyay, Bibhash Chakraborty and Asit Bose for patiently answering our queries; Alok Deb of Pratikriti for providing us the production details of Kenaram Becharam; Abhijit Kar Gupta of Chokh, who has readily answered/ provided the correct sources. -

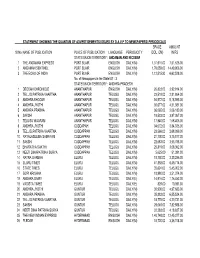

Statement Showing the Quantum of Advertisements

STATEMENT SHOWING THE QUANTUM OF ADVERTISEMENTS ISSUED BY D.A.V.P TO NEWSPAPERS/ PERIODICALS SPACE AMOUNT Sl No NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE OF PUBLICATION LANGUAGE PERIODICITY (COL .CM) IN RS STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,31,916.00 7,51,625.00 2 ANDAMAN SENTINEL PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,76,059.00 14,49,906.00 3 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,12,515.90 6,62,528.00 No. of Newspapers in the State/UT : 3 STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDHRA PRADESH 1 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 26,823.00 3,92,914.00 2 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,519.00 2,81,864.00 3 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 54,572.00 5,18,595.00 4 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 30,677.00 4,31,381.00 5 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 36,065.00 2,06,189.00 6 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,533.00 3,87,367.00 7 TELUGU WAARAM ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 17,940.00 1,68,405.00 8 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 34,072.00 3,84,335.00 9 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,566.00 2,68,399.00 10 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 21,700.00 3,75,877.00 11 SAKSHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 22,683.00 3,95,788.00 12 BHARATHA SAKTHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 25,819.00 3,08,362.00 13 NEETI DINAPATRIKA SURYA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 5,625.00 51,391.00 14 RATNA GARBHA ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,750.00 3,33,285.00 15 ELURU TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 41,858.00 6,49,774.00 16 STATE TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 35,624.00 -

Bengali Journal)

UnUnUniversityUn iversity of Calcutta DATABASE OF JOURNALS (OLD ISSUES) CENTRAL LIBRARY (Bengali Journal) Title Language Frequency Publisher Place ISSN Status Holdings Note Agrani Bengali Yearly Agrani Press Kolkata Discontinued V.8,1362; v.9,1363; v.10,1364 Archana Bengali Monthly Archana Kolkata Discontinued V.13,1322-1323; Karjalaya v.50,1359-1360 Aneek Bengali Monthly Dipankar Khagra, Active V.35,no.(8-12),1999; Chakrabarty Murshidabad v.36,no.(1-6), 1999; no.(Jan-Dec),2000; no.(Jan-July),2001; v.38,no.(1-12),2001; v.39,no.(1-6), 2002; no.(Jan-Dec), 2002; v.40,no.(7-11),2004; v.41,no.(1-3),2004; v.42,no.(Jan-June),2006; v.43,no.(7-12),2007; v.44,no.(1,3,6),2007; Anubad Bengali Baisampayan Kolkata Discontinued Saradiya, 1405 (1998); Patrika Ghose Saradiya, 1412 (2005); Anustup Bengali 3 issue per Anustup Kolkata Active V.2, 1374; v.20,no.(1),1985; 911 UnUnUniversityUn iversity of Calcutta Title Language Frequency Publisher Place ISSN Status Holdings Note year Karyalaya v.22, no.(2-3),1395; v.27, no.(4),1993; v.28, no.(2),1994; v.32,no.(3-4),1998; v.33,no.(2- 4),1999; v.34, no.(1-4), 1999- 2000; v.35, no.(1-4), 1407-08; v.36, no.(1-3), 2002; v.37, no.(1-4), 2002-03; v.38, no.(1- 4),2003-04; v.39, no.(1-4), 2004-05; v.Saradiya Anustup, 1412; v.40, no.(2-4), 1412; v.41, no.(1-4), 2006-07; v.42, no.(1-3), 1414(2008); v.43, no.(1-4), 2008-09; Amrita Bengali Amrita Kolkata Discontinued V.2,no.(1-25,38),1369; Karjalaya v.4,no.(28),1371; v.6,1373; v.8,no.(25-38),1375; v.15,1382 Amritaloke Bengali Amritaloke Midnapore 0971-4308 Active V.17,no.(2),1993; -

Status of Women Journalists in the Print Media

CHAPTER-1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY STATUS OF WOMEN JOURNALISTS IN THE PRINT MEDIA By Pamela Bhagat INTRODUCTION The project on the Status of Women Journalists in the Print Media was initiated by the National Commission for Women to look into issues affecting the role of women working in the print media. As part of a broader study on working women in India, it was executed by the Press Institute of India (PII), through empirical data that was collected from almost all the States and Union Territories of the country. The objective of the research was to examine the problems and issues confronting women working in the media, to gauge the extent of direct and indirect discrimination in the workplace and to identify contemporary issues that need to be addressed. METHODOLOGY The research was coordinated by me with the support of media representatives from various regions - Linda Chhakchhuak from Shillong, Rajashri Dasgupta from Calcutta, Sushmita Malaviya from Bhopal, R. Akhileshwari from Hyderabad and Surekha Sule from Mumbai - who together formed a National Study Group. The National Study Group assisted with the design and implementation of the 20-page questionnaire. Usha Rai, Deputy Director, Press Institute of India, guided and steered the group. A brain storming session with a focus group of women journalists in Delhi preceded the study, to ensure that the questionnaire was suitable and that critical aspects were addressed. The questionnaire was then pilot tested to iron out discrepancies and ambiguities. Experiences from the field surveys are outlined later in the report. SAMPLING AND RESPONSE RATE A total of 410 women working in the print media responded. -

Soviet Active Measures in the Era of Glasnost

SOVIET ACTIVE MEASURES IN THE ERA OF GLASNOST A Report to Congress by the United States Information Agency March 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW 1 DISINFORMATION IN THE MEDIA 4 Overview 4 Recent Appearances of Soviet Disinformation 7 AIDS Disinformation 10 The Ethnic Weapon 12 The 1978 Jonestown Mass Suicide 24 Body Parts Misinformation and Disinformation 32 Biological Warfare 50 Assassinations 50 FORGERIES 51 Characteristics of Soviet Forgeries 51 Silent Forgeries 52 Recent Forgery Activity 52 Copies of Recent Forgeries 56 FRONT GROUPS AND SOVIET MASS ORGANIZATIONS 57 Introduction 57 Recent Developments 57 COVERT MEDIA PLACEMENTS IN NIGERIA 61 Overview 61 USIS Lagos Report 64 Media Placements Using Disguised Attribution 64 Principal Themes 65 How Its Done 66 The Scope of Soviet Disinformation in Nigeria 68 SOVIET DISINFORMATION IN INDIA 71 Overview 71 USIS New Delhi Report 72 Major Disinformation Campaigns Since 1984 72 Subsidiary Disinformation Campaigns 74 Countering Soviet Disinformation 80 Analysis of Disinformation Trends 84 THE U.S. GOVERNMENT EFFORT TO COUNTER 86 SOVIET ACTIVE MEASURES The Organizational Structure 86 Efforts to Counter Soviet Active Measures 86 U.S. Versus Soviet Efforts 88 Budgetary Implications 89 FOOTNOTES 91 APPENDIX: SOVIET DISINFORMATION DURING PERIODS OF RELAXED EAST-WEST TENSIONS 1 OVERVIEW Active measures are carefully crafted influence operations, often covert or deceptive, which-the Soviets use, in addition to traditional diplomatic and informational activities, to support Soviet foreign policy. They range from the crude to the sublime, from vicious anti-American disinformation and forgeries to sophisticated, soothing influence operations. Soviet active mea- sures include: 0 Black KGB activities such as disinformation and forgeries. -

BENGALI Phone : + 91- 33-2414-6666 Fax : 91- 33- 2414-6008 Int

AR 2009 / 37 BENGALI Phone : + 91- 33-2414-6666 Fax : 91- 33- 2414-6008 Int. : 2232/2124 H.O.D : Dr. Ananya Barua E-mail: [email protected] .A1 . Course Offered : (Name of the course, Duration of course, No. of Students enrolled) B.A 3yrs no. of students – 150. M.A. 2Yrs no of students (Day & Evening) — 240 approx. M.Phil semester no. of student — 15. PhD scholar — 09 (With fellowship). B. Number of Faculty Member : Total : 16 (with lien 02) C. Area of Research Activity : Thurst area for DRS (under SAP) : Eastern Indian Society, Culture, Literature & Language : A Comprehensive and Comparative Study (With special reference to the indigenous ethnic groups of the region) D. Major Research Project : (Departmental/ Individual, Name of the project/ Funding Agency) 1. “Orally Performed Literature of the Painters of Southern Bengal : Video Recording, Digitalizing and to find out its Linguistic Features of Orality” — Prof. Udaykumar Chakraborty, UGC. 2. “Bengali Drama, Theatre of Bengal : Tradition and Modernity “ — Prof. Sekharkumar Samaddar, MRP, UGC. 3. “Partition : In the view of Class Response” — Dr. Ananya Baruya. 2.A. Invited Lectures Delivered/ Session Chaired Prof. Pinakeshchandra Sarkar 1. Delivered a lecture on ‘Western Impact on Tagore’s Poetry’ at Tagore Research Institute on Nov 16, 2008. 2. Delivered a lecture on “Kallol theke Krittibas : Bangla Little Magazine O Adhunik Bangla Kobita” as a resorse person in the Bengali Refresher Course organized by Jadavpur University on Nov 18, 2008. 3. Delivered a lecture on “Tagore’s Poetry : Pre-Manasi Phase” at Tagore Research Institute on Nov 23, 2008. 4. -

Bullets to Ballots: Maoists and the Lure of Democracy in India

BULLETS TO BALLOTS: MAOISTS AND THE LURE OF DEMOCRACY IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Government of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Rumela Sen January 2017 © 2017 Rumela Sen BULLETS TO BALLOTS: MAOISTS AND THE LURE OF DEMOCRACY IN INDIA Rumela Sen Cornell University 2017 Executive Summary How do insurgents give up arms and return to the same political processes that they had once sought to overthrow? A lot has been written on why men and women rebel, but we know very little about how rebels quit. This dissertation lays out the pro- tracted process of retirement of Maoist rebels through informal exit networks that grow in the grey zones of insurgency-democracy interface in India. Based on fine-grained fieldwork in conflict zones in North and South India, I argue that the biggest fear of retiring rebels is that they could be killed as soon as they disarmed, potentially by their former enemies, by former comrades, or by various state agencies. The state policies for surrender and rehabilitation, however, focus on post retirement livelihood provisions without addressing this apprehension of rebels that hinders retirement. During intimate conversations with the author former rebels com- plained that while they could possibly lose their lives after disarming, the state would not lose much if retired rebels were killed. This creates a problem of credible com- mitment, which, I show, is resolved locally by the informal exit networks that flourish in the shadow of grassroots associations of civic participation. -

A History of Arsenic Pollution Communication in West Bengal In

A History of Arsenic Pollution Communication in West Bengal in the light of Bengali Print Media (1982-2012) Malyaban Chattopadhyay Research Scholar of History, University of Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal Water is essential for the existence of everyone. Now a day’s water pollution has been emerging as an important environmental problem. There are two sources of water one is surface and another is subsurface water. In this present research I would like to explore the nature of a subsurface water pollution communication i.e. arsenic pollution communication in the light of Bengali print media of West Bengal (here after W.B). Arsenic is a natural component of the earth’s outer layer and is widely distributed throughout the environment in the air, water and land. It is highly toxic in its inorganic form. People are exposed to elevated levels of inorganic arsenic through drinking contaminated water, using contaminated water in food preparation and irrigation of food crops, industrial processes, eating contaminated food. World Health Organization says that the greatest threat to public health from arsenic originates from contaminated groundwater. Inorganic arsenic is naturally present at high levels in the groundwater of a number of countries, including Argentina, Bangladesh, Chile, China, India, Mexico, and the United States of America.1 If we go through some statistics related to the global water volume then it can be said that only 0.58% of Global Water Volume is originated from ground water and soil moisture.2 But in case of W.B as well as India this source became a crucial source to get drinking water or water for agriculture. -

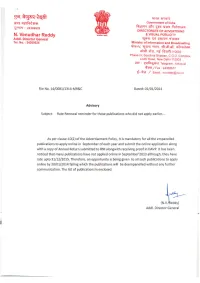

Rate Renewal Reminder for Those Publications Who Did Not

~.~R~¢ 'l1ffir m<PR 3TtR Si61f.'J~~ Government of India 'i~ l1Yffi f.R"mt>n.l ~: 24369526 ~ ~ Iq"1 31R DIRECTORATE OF ADVERTISING N. Venudhar Reddy & VISUAL PUBLICITY Add!. Director General ~~ ~ lfflRUT Ti~ Tel. No. : 24369526 Ministry of Information and Broadcasting ~\if-IV, ~~ 'IlCFf. ~.\Jfbn. ~<ffi "ffil:fi xt? ~ ~-110003 Phase-IV, Soochna Bhawan, c.G.a. Complex, Lodhi Road. New Delhi-110003 OR : ~3R1 Telegram: Advisual ~<ffi / Fax: 24369677 ~-~(>J / Email: [email protected] As per c1ause-10(2) of the Advertisement Policy, It is mandatory for all the em panelled publications to apply online in September of each year and submit the online application along with a copy of Annual Return submitted to RNI alongwith receiving proof in DAVP. It has been noticed that many publications have not applied online in September'20B although, they have rate upto 31/12/2015. Therefore, an opportunity is being given to all such publications to apply online by 30/01/2014 failing which the publications will be deempanelled without any further communication. The list of publications is enclosed. (N.V. eddy) Add!. Director General NP Code NP Name Periodicity Pub City 410512 NAVEENA VIDYA MONTHLY HYDERABAD 310662 KNOWLEDGE MEDIA WEEKLY AGARTALA 310573 TRIPURA SUNDARI DAILY(E) AGARTALA 131000 CITIZEN POWER MONTHLY AGRA 130169 JEEVAN NIDHI MONTHLY AGRA 130934 SACH KA UJALA DAILY(E) AGRA 210222 AVIRAT FORTNIGHTLY AHMEDABAD 210545 GUJARAT PRANAM DAILY(M) AHMEDABAD 210578 PRACHALIT DAILY(M) AHMEDABAD 210173 PRAJAJAN WEEKLY AHMEDABAD 210298 PUSHTI PARAG WEEKLY AHMEDABAD -

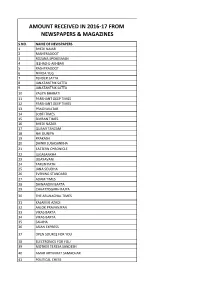

Annexure -A, for the Year 2016-17.Xlsx

AMOUNT RECEIVED IN 2016-17 FROM NEWSPAPERS & MAGAZINES S.NO. NAME OF NEWSPAPERS 1 BHEDI NAJAR 2 RASHTRADOOT 3 ROZANA SPOKESMAN 4 JEEHAD-E-AKHBAR 5 RASHTRADOOT 6 NIVIDA YUG 7 TENDER SATTA 8 JANATANTRIK SATTA 9 JANATANTRIK SATTA 10 YAGYA BHARATI 11 PARSHANT DEEP TIMES 12 PARSHANT DEEP TIMES 13 PRAGYAVATAR 14 SOBTI TIMES 15 SIMRAN TIMES 16 BHEDI NAZAR 17 QUAMI TANZAM 18 NAI DUNIYA 19 PRAKASH 20 DAINIK JUGASANKHA 21 EASTERN CHRONICLE 22 JUGASANKHA 23 UDAYAVANI 24 TARUN PATH 25 JANA SOUDHA 26 EVENING STANDARD 27 ADAM TIMES 28 DAINANDIN BARTA 29 CHHATTISGARH RAJYA 30 THE ARUNACHAL TIMES 31 KALAM KI AZADI 32 AALOK PRAVANJYAN 33 VIKAS BARTA 34 VIKAS BARTA 35 SALAHA 36 ASIAN EXPRESS 37 OPEN SOURCE FOR YOU 38 ELECTRONICS FOR YOU 39 MOTHER TERESA SANDESH 40 AMAR ARYAVRAT SAMACHAR 41 POLITICAL CHESS 42 SIRC NEWS LETTER 43 ABHIMANYU 44 PANKHRIAN 45 AGNIVARSHA 46 AIENA E CHASHM 47 MOOD OF INDIA 48 UBHARTA HARYANA 49 APNA BHARAT 50 NEWS COVER STORY 51 JYOTHISHAMALA 52 MARO PRASTHANAM 53 JANA JAGRUTHI 54 UDYOGULA GONTUKA 55 CRIME LOOK 56 SEEMA PRABHA 57 INDUSTRIAL VIEW 58 HOMOEO TODAY 59 TELANGANA SANJEEVINI 60 SHEETAL VANI 61 OMEGA NEWS 62 SEVEN NEWS 63 SNEHAWAANI 64 NEWS 13 65 NEWS 13 66 NEWS COVER STORY 67 NEWS COVER STORY 68 NEWS 13 69 NEWS 13 70 NEWS COVER STORY 71 PRAJAVELUTHURU 72 PUNJAB KESARI 73 JANAYUGOM 74 JANSATTA 75 INDIAN EXPRESS 76 BAKTHI SAMACHARAM 77 VIZAG METRO 78 HAKKIM 79 STUDENT LIFE 80 SAMACHARA BHARATHI 81 THE MILLENIUM ENGLISH 82 JANA PRABHANJANA VAHINI 83 PADMA PEETHAM 84 PRAJA DHWANI 85 VISWA SAKSHI 86 ASAM BANI 87 DAINIK ASSAM