College Radio Curricula: Las Vegas General Manager Views

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

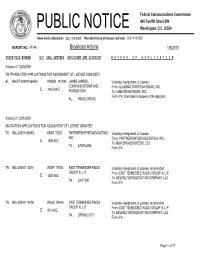

Broadcast Applications 12/2/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28377 Broadcast Applications 12/2/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N LOW POWER FM APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED AL BNPL-20131112AAC NEW 194121 NORTH SHELBY COMMUNITY Engineering Amendment filed 11/28/2014 RADIO E 93.3 MHZ AL , PELHAM FL BMPL-20141125AZY WJRQ-LP HISPANIC WOMEN OF Engineering Amendment filed 11/26/2014 192905 POINCIANA CORP E 97.1 MHZ FL , POINCIANA AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING NV BAL-20141126AJK KDWN 54686 KDWN LICENSE LIMITED Voluntary Assignment of License PARTNERSHIP E 720 KHZ From: KDWN LICENSE LIMITED PARTNERSHIP NV , LAS VEGAS To: BEASLEY MEDIA GROUP, LLC Form 316 NC BAL-20141126AJO WYDU 39240 WDAS LICENSE LIMITED Voluntary Assignment of License PARTNERSHIP E 1160 KHZ From: WDAS LICENSE LIMITED PARTNERSHIP NC , RED SPRINGS To: BEASLEY MEDIA GROUP, LLC Form 316 NJ BAL-20141126AJV WTMR 24658 WTMR LICENSE LIMITED Voluntary Assignment of License PARTNERSHIP E 800 KHZ From: WTMR LICENSE LIMITED PARTNERSHIP NJ , CAMDEN To: BEASLEY MEDIA GROUP, LLC Form 316 Page 1 of 23 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28377 Broadcast Applications 12/2/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER -

Komp Kxpt Kwwn Kkgk Vegas Golden Knights Playoff Ticket Giveaway

KOMP KXPT KWWN KKGK VEGAS GOLDEN KNIGHTS PLAYOFF TICKET GIVEAWAY No Purchase or obligation necessary to win CONTEST DESCRIPTION: Registration: June 14, 2021 – June 16, 2021 Requirements: must be a Nevada resident 21 years of age or older and have a valid Nevada Driver’s License or Government Issued photo Identification Card, and a valid social security number. Grand Prize winner will 2 tickets to see The Vegas Golden Knights vs Montreal Canadiens on Wednesday, June 16, 2021 at T Mobile Arena.. Tickets valued at approximately $250 and provided by The Vegas Golden Knights for promotional purposes. HOW TO ENTER/WIN: To participate, listeners must do the following: 1. From June 14, 2021 through June 16, 2021 listeners will be instructed to be a specific numbered caller on each stations designated request/listener line. (KOMP- 702 876 3692, KXPT 702 647 6468, KWWN 702 364 1100, and KKGK 702 876 1340). That caller will win a VGK hat provided by The VGK for promotional purposes and valued at approximately $20 and a 2 foot sub sandwich valued at approximately $20 provided by Port of Subs for promotional purposes. That caller will also qualify to win the grand prize. 2. On June 16, 2021 a grand prize random drawing will be conducted from all of the qualifiers from all stations and one grand prize winner will be selected. The grand prize winner name will be announced on the air. Grand prize winner will be notified by phone and/or email mail. 3. The winner must have a AXS ticket account to claim the grand prize ELIGIBILITY RESTRICTIONS: 1. -

Lana-Del-Golazo-Bmf-July-2021.Pdf

Reglas Oficiales 1. Nombre de la Promoción: ¡La Lana Del Golazo! NO ES NECESARIA LA COMPRA O EL PAGO ALGUNO PARA PARTICIPAR O GANAR. LA COMPRA NO MEJORARÁ SUS OPORTUNIDADES DE GANAR. INVALIDO DONDE PROHIBIDO. 1. Nombre y dirección del Patrocinador: Las estaciones de Univision Radio Inc., en; Los Ángeles, Inc., d/b/a KSCA 101.9FM con oficinas en 5999 Center Drive, Los Ángeles, CA 90045; San Francisco, Inc., d/b/a KSOL/KSQL 98.9 & 99.1FM con oficinas en 1940 Zanker Rd, San Jose, CA 95112; Phoenix, Inc d/b/a KHOT 105.9FM con oficinas en 6006 South 30th Street Phoenix, AZ 85042; Las Vegas, Inc., d/b/a KISF 103.5FM con oficinas en 6767 W. Tropicana Ave, ste 102 Las Vegas, NV 89103; Fresno, Inc d/b/a KOND 107.5FM con oficinas en 601 West Univision Plaza Fresno, CA 93704; Dallas, Inc., d/b/a KLNO 94.1FM con oficinas en 2323 Bryan St suite 1900, Dallas, TX 75201; Chicago, Inc., d/b/a WOJO 105.1FM con oficinas en 541 N. Fairbanks Ct, Ste 1100 Chicago, IL 60611; NM 87110;; Austin, Inc., d/b/a KLQB 104.3 FM con oficinas en 2233 W. North Loop Blvd, Austin, TX 78756 y las afiliadas siguientes: Nashville, Inc, d/b/a WNVL 105.1FM con oficinas en 3955 Nolensville Pike, Nashville, TN 37211; Greenville, Inc d/b/a WTOB 103.9 FM y 105.7 FM, 910AM con oficinas en 225 S. Pleasantburg Drive STE B-3 Greenville, SC 29607; Denver, Inc, d/b/a KBNO 97.7FM and 1280 AM con oficinas en777 Grant ST. -

Who Pays Soundexchange: Q1 - Q3 2017

Payments received through 09/30/2017 Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 - Q3 2017 Entity Name License Type ACTIVAIRE.COM BES AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES AURA MULTIMEDIA CORPORATION BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX MUSIC BES ELEVATEDMUSICSERVICES.COM BES GRAYV.COM BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IT'S NEVER 2 LATE BES JUKEBOXY BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MEDIATRENDS.BIZ BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES MUSIC CHOICE BES MUSIC MAESTRO BES MUZAK.COM BES PRIVATE LABEL RADIO BES RFC MEDIA - BES BES RISE RADIO BES ROCKBOT, INC. BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES STARTLE INTERNATIONAL INC. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STORESTREAMS.COM BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES TARGET MEDIA CENTRAL INC BES Thales InFlyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT MUSIC CHOICE PES MUZAK.COM PES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC SDARS 181.FM Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Christian Music) Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Religious) Webcasting 8TRACKS.COM Webcasting 903 NETWORK RADIO Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ABUNDANT RADIO Webcasting ACAVILLE.COM Webcasting *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright Act, and it does not waive the rights of artists or copyright owners that receive such payments. Payments received through 09/30/2017 ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting ACRN.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting ADORATION Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM CALIFORNIA - SAN LUIS OBISPO Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. -

NEVADA PUBLIC RADIO Local Content and Services Report 2017

NEVADA PUBLIC RADIO Local Content and Services Report 2017 1. Describe your overall goals and approach to address identified community issues, needs, and interests through your station’s vital local services, such as multiplatform long and short‐form content, digital and in‐person engagement, education services, community information, partnership support, and other activities, and audiences you reached or new audiences you engaged. Nevada Public Radio operates under a three year plan with current top line goals to grow audience on all platforms with an emphasis on reaching a younger more diverse audience. Organizationally we worked on a partnership with the University of Nevada Las Vegas to leverage our efficiencies in a local management agreement that would enhance the quality of student opportunities while relieving UNLV of expense and presenting the community with a station designed to appeal to a “younger than the npr” audience. Unfortunately that did not come to fruition. NVPR has been a first wave adopter of NPR ONE and other NPR initiatives to grow a digital audience, one proven to be younger and more diverse than broadcast. In 2016, we hired our first marketing manager to accelerate social media engagement. In the 13th year of our weekday original content KNPR’s State of Nevada, we continue to refine our editorial efforts with a full staff supported with an online editor. Responding to some critical issues in our community we’ve instituted a beat system to cover education (5th largest school district is under reorganization), a tax hike to support an NFL stadium project, “new Nevada” with Tesla and green energy investment and the successful effort to legalize recreational marijuana in the state. -

Progress Report Forest Service Grant / Agrreement No

PROGRESS REPORT FOREST SERVICE GRANT / AGRREEMENT NO. 13-DG-11132540-413 Period covered by this report: 04/01/2014—05/31/2015 Issued to: Center of Southwest Culture, Inc. Address: 505 Marquette Avenue, NW, Suite 1610 Project Name: Arboles Comunitarios Contact Person/Principal Investigator Name: Arturo Sandoval Phone Number: 505.247.2729 Fax Number: 505.243-1257 E-Mail Address: [email protected] Web Site Address (if applicable): www.arbolescomunitarios.com Date of Award: 03/27/2013 Grant Modifications: Date of Expiration: 05/31/2015 Funding: Federal Share: $95,000 plus Grantee Share: $300,000 = Total Project: $395,000 Budget Sheet: FS Grant Manager: Nancy Stremple / Address: 1400 Independence Ave SW, Yates building (3 Central) Washington, DC 20250-1151 Phone Number: 202/309-9873 Albuquerque Service Center (ASC) Send a copy to: Albuquerque Service Center Payments – Grants & Agreements 101B Sun Ave NE Albuquerque, NM 87109 EMAIL: [email protected] FAX: 877-687-4894 Project abstract (as defined by initial proposal and contract): Arboles Comunitarios is proposed under Innovation Grant Category 1 as a national Spanish language education program. By utilizing the expertise of the Center of Southwest Culture community and urban forestry partners along with the targeted outreach capacity of Hispanic Communications Network, this project will communicate the connection between the personal benefits of urban forest and quality of life in a manner that resonates specifically with the Hispanic community. Project objectives: • Bilingual website with -

Plan Ahead Nevada Brought to You by the State of Nevada, Department of Public Safety, Division of Emergency Management

TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW AND PREPAREDNESS LISTS INTRODUCTION LETTER PG. 3 STEP BY STEP PREPAREDNESS LIST PG. 4 FAMILY PREPAREDNESS PG. 6 At WORK PREPAREDNESS PG. 8 EVACUATION & SHELTER TIPS PG. 10 EMERGENCY COMMUNICATIONS PG. 11 BASIC EMERGENCY SUPPLY KIT PG. 12 TYPES OF DISASTER TO PREPARE FOR WILDLAND FIRE PG. 13 EARTHQUAKE PG. 14 FLOOD PG. 15 EXTREME WEATHER PG. 16 FLU PANDAMIC PG. 17 TERRORISM PG. 18 HAZARD MITIGATION WHAT IS HAZARD MITIGATION? PG. 19 MITIGATION FOR WILDFIRE PG. 20 MITIGATION FOR EARTHQUAKE PG. 20 MITIGATION FOR FLOODS PG. 21 YOUR COMMUNITY, YOUR PREPAREDNESS YOUR EVACUATION PLAN PG. 22 YOUR EMERGENCY CONTACTS PG. 23 MEDIA COMMUNICATIONS PG 24 YOUR COUNTY EVACUATION PLAN PG. 26 Plan Ahead Nevada Brought to you by The State of Nevada, Department of Public Safety, Division of Emergency Management. Content provided in part by FEMA. Funding Granted By U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2 STAT E DIVISION OF EM E RG E NCY MANAG E M E NT A MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF “Proudly serving the citizens of the State of Nevada, in emergency NEVADA preparedness response and recovery.” EMERGENCY MITIGATION GUIDE FRANK SIRACU S A , CHIE F This brochure, funded through the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, is the result of statewide participation from public safety officials and first responders in addressing “Preparedness Response and Recovery” emergency mitigation. It is developed to provide helpful tips and techniques in prepar- ing your family, friends and pets for emergency conditions. Hazard Mitigation is the cornerstone of the Four Phase of Emergency Management. The term “Hazard Mitigation” describes actions that can help reduce or eliminate long-term risks caused by natural hazards, or disasters, such as wildfires, earthquakes, thunderstorms, floods and tornadoes . -

Broadcast Actions 1/6/2010

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 47146 Broadcast Actions 1/6/2010 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 12/30/2009 FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE DISMISSED AL BALFT-20091106AAH W293BI 141199 JAMES JARRELL Voluntary Assignment of License COMMUNICATIONS AND From: ALABAMA CHRISTIAN RADIO, INC. E 106.5 MHZ FOUNDATION To: AUBURN NETWORK, INC. Form 314 Dismissed at request of the applicant AL , RIDGE GROVE Actions of: 12/31/2009 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED TX BAL-20091106AFD KEAS 70621 PARTNERSHIP BROADCASTING, Voluntary Assignment of License INC. From: PARTNERSHIP BROADCASTING, INC. E 1590 KHZ To: M&M BROADCASTERS, LTD. TX , EASTLAND Form 314 TN BAL-20091112AIV WDNT 70783 EAST TENNESSEE RADIO Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended GROUP III, L.P. From: EAST TENNESSEE RADIO GROUP III, L.P. E 1280 KHZ To: BEVERLY BROADCASTING COMPANY, LLC TN , DAYTON Form 314 TN BAL-20091112AIW WXQK 54469 EAST TENNESSEE RADIO Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended GROUP III, L.P. From: EAST TENNESSEE RADIO GROUP III, L.P. E 970 KHZ To: BEVERLY BROADCASTING COMPANY, LLC TN , SPRING CITY Form 314 Page 1 of 17 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. -

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1)

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1) Full Full Full Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation 2 Los Angeles, CA KTLA The CW 57 Mobile, AL WKRG CBS 111 Springfield, MA WWLP NBC 3 Chicago, IL WGN Independent WFNA The CW 112 Lansing, MI WLAJ ABC 4 Philadelphia, PA WPHL MNTV 59 Albany, NY WTEN ABC WLNS CBS 5 Dallas, TX KDAF The CW WXXA FOX 113 Sioux Falls, SD KELO CBS 6 San Francisco, CA KRON MNTV 60 Wilkes Barre, PA WBRE NBC KDLO CBS 7 DC/Hagerstown, WDVM(2) Independent WYOU CBS KPLO CBS MD WDCW The CW 61 Knoxville, TN WATE ABC 114 Tyler-Longview, TX KETK NBC 8 Houston, TX KIAH The CW 62 Little Rock, AR KARK NBC KFXK FOX 12 Tampa, FL WFLA NBC KARZ MNTV 115 Youngstown, OH WYTV ABC WTTA MNTV KLRT FOX WKBN CBS 13 Seattle, WA KCPQ(3) FOX KASN The CW 120 Peoria, IL WMBD CBS KZJO MNTV 63 Dayton, OH WDTN NBC WYZZ FOX 17 Denver, CO KDVR FOX WBDT The CW 123 Lafayette, LA KLFY CBS KWGN The CW 66 Honolulu, HI KHON FOX 125 Bakersfield, CA KGET NBC KFCT FOX KHAW FOX 129 La Crosse, WI WLAX FOX 19 Cleveland, OH WJW FOX KAII FOX WEUX FOX 20 Sacramento, CA KTXL FOX KGMD MNTV 130 Columbus, GA WRBL CBS 22 Portland, OR KOIN CBS KGMV MNTV 132 Amarillo, TX KAMR NBC KRCW The CW KHII MNTV KCIT FOX 23 St. Louis, MO KPLR The CW 67 Green Bay, WI WFRV CBS 138 Rockford, IL WQRF FOX KTVI FOX 68 Des Moines, IA WHO NBC WTVO ABC 25 Indianapolis, IN WTTV CBS 69 Roanoke, VA WFXR FOX 140 Monroe, AR KARD FOX WTTK CBS WWCW The CW WXIN FOX KTVE NBC 72 Wichita, KS -

Newspapers Nebraska Press Association (NPA)

411 SOUTH VICTORY 3 LITTLE ROCK AR 72201 NAA OFFERS FREE ARKANSAS Since 1873 4 SERIALIZED STORIES Publisher ‘A FEW WORDS Publisher ABOUT BUYING SIGNALS’ BY JOHN FOUST WEEKLY VOL. 11 | NO. 1 ° THURSDAY, JANUARY 7, 2016 SERVING PRESS and STATE SINCE 1873 Board elects Nat Lea president of APA APA recruiting judges The Arkansas Press Association (APA) 2016 convention when he will assume the role for Nebraska contest board of directors has elected Nat Lea, presi- of immediate past president on the APA board. This year’s Arkansas Press Association dent of Wehco Media, Inc. in Little Rock, to Other officers elected for the coming year (APA) Contests, both Advertising and News- serve as president next year. include Byron Tate, publisher of the Pine Blue Editorial, are being judged by members of the Lea will be installed on Friday, June 24, at Commercial and several other newspapers Nebraska Press Association (NPA). As part of a the annual SuperConvention to be held this owned by GateHouse Media, as vice president reciprocal arrangement between the two associ- year June 22-25 at the DoubleTree Hotel in and David Mosesso, publisher of The Sun in ations, APA has committed to judging the Bentonville. He will assume the office at the Jonesboro, as second vice president. Nebraska Press Association Better Newspaper conclusion of the convention. Other APA board members include Tom Contest. The installation will include the traditional White, publisher of the Advance APA is now looking for judges for the NPA “passing of the gavel” by APA past presidents Monticellonian of Monticello; Jay Edwards, contest. -

New Hampshire New Jersey

Radio Stations on the Internet *KMLV -88.1 FM- Ralston, NE WJYY-105.5 FM Concord, NH www.klove.com www.wjyy.com KNEB -960 AM- Scottsbluff, NE 'WVNH -91.1 FM- Concord, NH www.kneb.com www.wvnh.org KZKX -96.9 FM- Seward. NE WBNC -104.5 FM- Conway, NH www.kzkx.com www.valley1045.com KCMI -96.9 FM- Terrytown, NE WMWV-93.5 FM- Conway, NH www.kcmi.cc www.wmwv.com -1320 AM- KOAO -690 AM- Terrytown, NE WDER Derry, NH www.lifechangingradio.com www.tracybroadcasting.com WOKQ-97.5 FM- Dover, NH KTCH -1590 AM- Wayne, NE www.wokq.com www.ktch.com 'WUNH -91.3 FM- Durham, NH KTCH -104.9 FM- Wayne, NE www.wunh.unh.edu www.ktch.com WERZ -107.1 FM- Exeter, NH 'KWSC -91.9 FM- Wayne, NE www.werz.com www.wsc.edu /k92 WMEX -106.5 FM- Farmington, NH KTIC -840 AM- West Point, NE www.wzen.com www.kticam.com WFTN-94.1 FM- Franklin, NH KWPN-107.9 FM- West Point, NE www.mix941fm.com www.kwpnfm.com WSAK102.1 FM- Hampton, NH 'KFLV -89.9 FM- Wilber, NE www.shaark1053.com www.klove.com WNNH -99.1 FM- Henniker, NH KSUX -105.7 FM- Winnebago, NE www.wnnh.com www.ksux.com WYRY-104.9 FM- Hinsdale, NH www.wyry.com WEMJ -1490 AM- Laconia, NH Nevada www.wlnh.com KSTJ -105.5 FM- Boulder City, NV WEZS-1350 AM- Laconia, NH www.star1055.net www.wers.com KRJC -95.3 FM- Elko, NV WLNH-98.3 FM- Laconia, NH www.krjc.com www.wlnh.com KRNG -101.3 FM- Fallon, NV WXXK -100.5 FM- Lebanon, NH www.renegaderadio.org www.kixx.com KMZQ -100.5 FM- Henderson, NV WGIR-610 AM- Manchester, NH www.litelasvegas.com www.wgiram.com KWNR -95.5 FM- Henderson, NV WGIR-101.1 FM- Manchester, NH www.kwnr.com www.wgirtm.com KTHX -100.1 FM- Incline Village, NV WZID-95.7 FM- Manchester, NH www.kthxfm.com www.wzid.com KBAD -920 AM- Las Vegas, NV WBHG -101.5 FM- Meredith. -

Nevada Broadcasters Association Sober Moms Total Dollar Return

Sober Moms Total Dollar Return and Spots Aired For March 2016 Monthly Investment : $5000.00 Region Spots Aired Region Total Estimated Value Southern Radio 692 Southern Radio $69,200.00 Southern Television 321 Southern Television $53,025.00 Northern and Rural Radio 527 Northern and Rural Radio $39,525.00 Northern and Rural Television 960 Northern and Rural Television $151,800.00 Monthly Spot Total 2,500 Monthly Value Total $313,550.00 Campaign Spot Total 8,663 Campaign Value Total $1,095,120.00 Monthly Return on Investment 62:1 Total Return on Investment 54:1 Spots Aired Day Parts Spots Aired 35% 42% 6am to 7pm 6am to 7pm 871 7pm to 12am 573 7pm to 12am 12am to 6am 1056 23% 12am to 6am Station Frequency Format Spots Total Value* 6a-7p 7p-12a 12a-6a KBAD 920 AM Sports 9 $900.00 3 3 3 KCYE 102.7 FM Coyote Country 10 $1,000.00 0 0 10 KDWN 720 AM News/Talk 10 $1,000.00 0 0 10 KENO 1460 AM Sports 9 $900.00 3 3 3 KISF 103.5 FM Regional Mexican 23 $2,300.00 5 8 10 KJUL 104.7 FM Adult Standards 41 $4,100.00 4 27 10 KKLZ 96.3 FM Classic Rock 10 $1,000.00 0 0 10 KLAV 1230 AM Talk/Information 9 $900.00 3 3 3 KLSQ 870 AM Spanish Oldies/Talk 21 $2,100.00 10 2 9 KLUC 98.5 FM Contemporary Hits 42 $4,200.00 0 0 42 KMXB 94.1 FM Modern Adult Contemporary 44 $4,400.00 0 3 41 KMZQ 670 AM News/Talk 70 $7,000.00 35 15 20 KOAS 105.7 FM Jazz 10 $1,000.00 0 0 10 KOMP 92.3 FM Rock 8 $800.00 2 2 4 KPLV 93.1 FM Oldies 6 $600.00 1 0 5 KQLL 102.3 FM /1280 AM Oldies 24 $2,400.00 3 5 16 KQRT 105.1 FM Mexican Regional Music 36 $3,600.00 19 4 13 KRGT 99.3 FM Spanish Urban