'Ilo') Conventions, the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representations of Arab Men on Australian Screens

Heroes, Villains and More Villains: Representations of Arab Men on Australian Screens BY MEHAL KRAYEM Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology, Sydney December 2014 ii CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Name of Student: Mehal Krayem Signature of Student: Date: 5 December 2014 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many (too many) people to whom I owe a great deal of thanks. The last five years, and indeed this body of work, would not have been possible without the support and dedication of my wonderful supervisor, Dr Christina Ho. I thank her for taking a genuine interest in this research, her careful consideration of my work, her patience and her words of encouragement when the entire situation felt hopeless. I would also like to thank Professor Heather Goodall for her comments and for stepping in when she was needed. Much gratitude goes to my research participants, without whom this project would not exist – I thank them for their time and their honesty. Great thanks goes to Dr Maria Chisari, Dr Emma Cannen, Kelly Chan, Dr Bong Jong Lee, Jesica Kinya, Anisa Buckley, Cale Bain, Zena Kassir, Fatima El-Assaad and Chrisanthi Giotis for their constant support and friendship. -

Terror Nullius (2018) and the Politics of Sample Filmmaking

REVENGE REMIX: TERROR NULLIUS (2018) AND THE POLITICS OF SAMPLE FILMMAKING by Caitlin Lynch A Thesis SubmittEd for the DEgreE of MastEr of Arts to the Film StudiEs ProgrammE at ViCtoria University of WEllington – TE HErenga Waka April 2020 Lynch 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my supervisors, Dr. Missy Molloy and Dr. Alfio LEotta for their generous guidancE, fEEdbaCk and encouragemEnt. Thank you also to Soda_JErk for their communiCation and support throughout my resEarch. Lynch 3 ABSTRACT TERROR NULLIUS (Soda_JErk, 2018) is an experimEntal samplE film that remixes Australian cinema, tElEvision and news mEdia into a “politiCal revenge fablE” (soda_jerk.co.au). WhilE TERROR NULLIUS is overtly politiCal in tone, understanding its speCifiC mEssages requires unpaCking its form, contEnt and cultural referencEs. This thesis investigatEs the multiplE layers of TERROR NULLIUS’ politiCs, thereby highlighting the politiCal stratEgiEs and capaCitiEs of samplE filmmaking. Employing a historiCal mEthodology, this resEarch contExtualisEs TERROR NULLIUS within a tradition of sampling and other subversive modes of filmmaking, including SoviEt cinema, Surrealism, avant-garde found-footage films, fan remix videos, and Australian archival art films. This comparative analysis highlights how Soda_JErk utilisE and advancE formal stratEgiEs of subversive appropriation, fair usE, dialECtiCal editing and digital compositing to intErrogatE the relationship betwEEn mEdia and culture. It also argues that TERROR NULLIUS Employs postmodern and postColonial approaChes -

Australian Multicultural Policy and Television Drama in Comparative Contexts

Australian multicultural policy and television drama in comparative contexts Harvey May BA (Comm), BA, B Bus (Hons)(Comm), Post Grad Dip Ed A thesis submitted in 2003 for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Industries Research and Applications Centre Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology Key Words Multiculturalism, Cultural Diversity, Television, Drama, Casting, Minorities, Australia, United Kingdom, New Zealand, United States. Abstract This thesis examines changes which have occurred since the late 1980s and early 1990s with respect to the representation of cultural diversity on Australian popular drama programming. The thesis finds that a significant number of actors of diverse cultural and linguistic background have negotiated the television industry employment process to obtain acting roles in a lead capacity. The majority of these actors are from the second generation of immigrants, who increasingly make up a significant component of Australia’s multicultural population. The way in which these actors are portrayed on- screen has also shifted from one of a ‘performed’ ethnicity, to an ‘everyday’ portrayal. The thesis develops an analysis which connects the development and broad political support for multicultural policy as expressed in the National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia to the changes in both employment and representation practices in popular television programming in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The thesis addresses multicultural debates by arguing for a mainstreaming position. The thesis makes detailed comparison of cultural diversity and television in the jurisdictions of the United States, the United Kingdom and New Zealand to support the broad argument that cultural diversity policy measures produce observable outcomes in television programming. -

Annual Report 2014-2015

AUSTRALIAN FILM, TELEVISION AND RADIO SCHOOL Building 130, The Entertainment Quarter, Moore Park NSW 2021 PO Box 2286, Strawberry Hills NSW 2012 Tel: 1300 131 461 Tel: +61 (0)2 9805 6611 Fax: +61 (0)2 9887 1030 www.aftrs.edu.au © Australian Film, Television and Radio School 2015 Published by the Australian Film, Television and Radio School ISSN 0819-2316 The text in this Annual Report is released subject to a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND licence, except for the text of the independent auditor’s report. This means, in summary, that you may reproduce, transmit and otherwise use AFTRS’ text, so long as you do not do so for commercial purposes and do not change it. You must also attribute the text you use as extracted from the Australian Film, Television and Radio School’s Annual Report. For more details about this licence, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ deed.en_GB. This licence is in addition to any fair dealing or other rights you may have under the Copyright Act 1968. You are not permitted to reproduce, transmit or otherwise use any still photographs included in this Annual Report, without first obtaining AFTRS’ written permission. The report is available at the AFTRS website http://www.aftrs.edu.au Cover Image: Production still from AFTRS student film Foal 2014. Photo courtesy of Vanessa Gazy. LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 28 August 2015 Senator the Hon Mitch Fifield Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister It is with great pleasure that I present the Annual Report for the Australian Film, Television and Radio School (AFTRS) for the financial year ended 30 June 2015. -

Riot and Revenge: Symmetry and the Cronulla Riot in Abe Forsythe's

Riot and Revenge: Symmetry and the Cronulla Riot in Abe Forsythe’s Down Under Kenta McGrath Abstract: Abe Forsythe’s Down Under (2016) is the first narrative feature film about the Cronulla riot—the infamous event on 11 December 2005 where over 5000 white Australians, responding to a minor local incident, descended on Cronulla Beach in Sydney and proceeded to harass, chase and bash anybody who they perceived to be of Middle Eastern appearance. In the following nights, a series of violent retaliatory attacks took place, as community leaders called for calm. Suvendrini Perera identifies how a symmetrical narrative had emerged in the wake of the riot and its aftermath, whereby Cronulla Beach “comes to stand for a paired sequence of events, the riot and the revenge, in a fable of equivalence in which two misguided groups . mirror each other’s ignorance and prejudices”. This article considers how Down Under reinforces the distortive implications of this “riot and revenge” narrative by maintaining a structural equilibrium—through the rigorous balancing of its narrative and characters, and formally, via its soundtrack, cinematography and editing patterns. In so doing, and despite its antiracist sentiments, the film ultimately dilutes the issue of race and obscures the power imbalances that informed the riot, and which continue to this day. Introduction During the first week of December 2005, news of an incident on Cronulla Beach spread throughout Sydney: three white off-duty lifesavers had been involved in an altercation with four young men of Lebanese background and were bashed. Within the Sutherland Shire—known colloquially as “The Shire”, a predominantly Anglo area of southern Sydney which includes Cronulla Beach—a sense of communal outrage gained momentum as news, rumours and misinformation about the incident circulated. -

13/Australian Hip Hop's Multi

AUSTRALIAN HIP HOP’S MULTI- 13/ CULTURAL LITERACIES / A SUBCULTURE EMERGES INTO THE LIGHT / TONY MITCHELL uch has been written in recent years about the relationship between hip hop Mculture, pedagogy and youth literacies in an African-American context (Ibrahim 2003; Dimitriades 2004; Ginwright 2004; Richardson 2006). However, hip hop is also being used increasingly in the broader educational contexts of language learning and popular culture studies both in the US and throughout the rest of the world. Hip Hop Studies is now a discipline taught in US universities (Forman & Neal 2004) and is gradually spreading to educational contexts in other parts of the world. In Hiphop literacies, Elaine Richardson (2006) argues for “the depth, the importance, and the immediate necessity of acknowledging one of the most contemporary, accessible, and contentious of African American literacies, Hiphop literacies” (p.xv). She sets out to locate hip hop discourses “within a trajectory of Black discourses” and to consider hip hop as an oral and semiotic form of discourse, analysing “rap music and song lyrics, electronic and digital media, including video games, music videos, telecommunication 231 SOUNDS OF THEN, SOUNDS OF NOW / POPULAR MUSIC IN AUSTRALIA devices, magazines, ‘Hip hop’ novels, oral performances, and cinema” (Richardson 2006, p.xvi). Richardson’s study is restricted by two major limitations. Apart from looking at the use of African-American language in online German hip hop sites, neither considers the indigenising global spread of hip hop beyond the boundaries of African-American vernacular cultures, nor the non-linguistic but fundamentally semiotic aspects of hip hop such as beatboxing, DJing, breakdancing and graffiti writing, which are arguably of equal importance to MCing as hip hop literacies. -

Go Betweens 1426

PRESSPRESS KITKIT THE PRODUCTION: A feature documentary written & directed by KRIV STENDERS EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS David Alrich & Chris Hilton PRODUCER Joe Weatherstone CO-PRODUCER Kriv Stenders ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Penelope Jope EDITOR Karryn de Cinque DOP Mark Broadbent PRODUCTION COMPANY Essential Media and Entertainment DISTRIBUTOR Umbrella Entertainment DURATION 90 - 95 mins (TBC) CLASSIFICATION TBC RELEASE DATE 2017 WORLD PREMIERE Sydney Film Festival 2017 The Go-Betweens: Part CompanyScreen NSW – ABC TV Arts Documentary Feature Fund. Screen Australia © 2017 Essential Media and Entertainment 1 ONE LINE SYNOPSIS The Go-Betweens: Part Company uncovers the intensely passionate, creative and fraught relationships behind one of the most loved and influential bands in Australian rock history. SYNOPSIS The Go-Betweens : Part Company is the feature length documentary about the people who created the seminal rock band the Go-Betweens. © JEREMY BANNISTER It is a heartfelt story of discovery, uncovering the intensely passionate, creative and fraught relationships that formed one of the most loved and influential bands in Australian rock history. It is also the universal story of a great creative adventure that spanned three decades, through countless successes, failures, romances, break-ups, betrayals, triumphs and tragedies. The Go-Betweens: Part Company is a compelling investigation into the exhilarating, unpredict- able, and precarious lives of musicians, that reveals the true price paid by them to pursue their art. Directed by Kriv Stenders. The Go-Betweens: Part Company doesn’t assume knowledge of the band or their music, rather it offers an evolving revelation of them that truthfully exposes all the highs, the lows, the joy, the pain, the sorrow, and the beauty of being in a cult band and of trying to survive the harsh and brutal realities of an exploitative music industry. -

Flickerlab SESSION: from IDEA to PAGE 10.00Am

FLiCKERLAB A ONE-DAY JOURNEY FROM SHORTS TO FEATURES PRESENTED BY SAE Friday 18th January 10am - 5pm SESSION: FROM IDEA TO PAGE 10.00am – 11.30am Everyone will tell you a good script is an essential ingredient for any good film. Our panel of experienced screenwriters will discuss turning a good idea into a good script, looking in detail at development, collaboration and script editing. They will share their insights about their own transitions from independent shorts to lauded feature films. Discussions will also include observations about writing for some of television’s most successful and acclaimed dramas. This valuable session is a must for all budding screenwriters and filmmakers looking to develop and write scripts. WRITERS PANEL moderated by LOUISE GOUGH from Arenamedia feat. John Collee and Alena Lodkina JOHN COLLEE Writer/Producer John studied Medicine in Edinburgh, Scotland, and subsequently worked as a doctor in the UK and overseas. From 1991-96 he wrote a popular weekly medical column for The Observer Newspaper, UK. His novels - all published by Penguin - include “Kingsley's Touch”, “A Paper Mask” and “The Rig”. Since moving to Sydney in 1998 he has written or co-written a number of feature films including the Oscar nominated Master and Commander and the Oscar winning Happy Feet. More recent work includes Creation, Walking with Dinosaurs, Wolf Totem and Tanna, nominated for best foreign language Oscar. Current/upcoming projects include Hotel Mumbai. John is creative director of Hopscotch Features, also co-founder and board member of the climate action group 350.Org Australia. PARTHO SEN-GUPTA Writer/Director Partho is a film writer and director. -

Production Notes Dumb Criminals

PRODUCTION NOTES DUMB CRIMINALS Writer, Producer, Director: Paul Fenech Rabbit Productions Pty Ltd, A Transmissions Films Release Release Date: 21st October, 2015 Running time: 91 minutes Classification: CTC PUBLICITY REQUESTS Kabuku Public Relations (02) 9690 2115 Belinda Dyer [email protected] or 0415 686 014 Marissa Giannone [email protected] or 0421 801 929 Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films, 3 Little Collins St, Surry Hills NSW 2010 SYNOPSIS DUMB CRIMINALS – THE MOVIE THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE STUPID. From cult comedy hero Pauly Fenech comes ‘Dumb Criminals: The Movie’. Real dumb crimes recreated with the fictional wannabe gangsters; Rabbit, Rongo, Jimmy the Junkie, Pothead and Droptank. The crew lead by Rabbit (Paul Fenech) are on a mission to raise money to buy expensive medical care for a sick little girl. Dumb crimes, for a good cause. Sadly our anti-heroes fumble, bumble and stumble, often failing miserably. Their final mission, a hit on a dodgy accountant in Las Vegas. Can they over come their own stupidity to save the day? SYNOPSIS Based on real dumb crimes from all over the world, cult comedy hero Pauly Fenech reunites his comedy ensemble, including Angry Anderson, Elle Dawe and Kevin Taumata. The film follows 5 really stupid criminals trying to steal money in order to help save the life of a little girl who needs expensive medical treatment. Rabbit (Pauly Fenech) is the brains of the crew a wannabe bikers. He has many enemies including a ‘roid raging bikey called Tiny. Rongo (Kevin Taumata) is Rabbit’s best mate and the muscle of the crew. -

Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014 “Since its inception, SBS has grown into a world renowned leader in multicultural broadcasting, and the service that SBS provides ensures that millions of Australians from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds are actively engaged in Australian society.” – Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia, June, 2014. Contents About SBS 3 Letter to the Minister 4 SBS: Australia’s unique 6 broadcaster Organisational Structure 8 SBS Board of Directors 9 SBS Executive 12 Our Strategic Objectives 14 Year at a Glance 16 Content that explores and 18 celebrates diversity Organisation 52 Financial Statements 74 Appendices 134 Index of Annual Report 176 Requirements 2 SBS Annual Report 2014 SBS was established as an independent statutory authority on 1 January 1978 under the Broadcasting Act 1942. In 1991 the Special Broadcasting Service Act 1991 (SBS Act) came into effect and SBS became a corporation. The Minister responsible is the Honourable Malcolm Turnbull, Minister for Communications. During 2013-14 there was one other responsible Minister, the Honourable Anthony Albanese, Minister for Broadband, Communication and the Digital Economy (1 July to 18 September 2013). Charter The Charter of SBS, which sets out our principal function and duties, is contained in the SBS Act. (1) The principal function of SBS (e) as far as practicable, is to provide multilingual and inform, educate and multicultural radio, television entertain Australians in and digital media services their preferred languages; that inform, educate -

The Black List Is an Important Addition to Reference Material B

T h e Produced by Screen Australia’s Strategy & Research Unit, The Black List is an important addition to reference material B on Indigenous filmmaking in Australia, cataloguing the work l a of 257 Indigenous Australians with credits as producer, c director, writer or director of photography on a total of k 674 screen productions. L he i Listings go back as far as 1970 for feature films and telemovies, ! Film and TV to 1980 for documentaries and mini-series, and to 1988 for T shorts and series. projects since 1970 Titles are indexed by year and by filmmaker, and the book with also features a statistical summary and timeline of key titles and events. Indigenous Australians in key creative SCREEN A Black roles US TRALIA Li! he OVX:YD+1 T cf[TEChg gOYCEÐÖõÏ pOhM YDOLEY[jg jghf:VO:Yg OYUErCfE:hOoE Black f[VEg Li! ÛÛ #!1!1/ 0 .0 Yhf[DjChO[YÒ _nSKi@mnQKvxK@lm_JURK_apm~\^^@[KlmS@uKHla[K_nSlapRSna@ISUKuKHanSIlUnUI@\@_J Ia^^KlIU@\mpIIKmmvUnS-@ISK\*Kl[U_m¡3`O\?bS5OSn@[U_R^alKnS@_ Ý^U\\Ua_@nnSK Mf[Y[V[Lr[K pmnl@\U@_HawaQ~IK7@lvUI[0Sal_na_vU__U_RnSK @__Km @^Kl@J¡"lQalO[]\5SZWZOV YDOLEY[jgxVXò+1Ó @_J^p\nUi\K@v@lJmQalilaRl@^mmpIS@m7W`a2ba`OZWO\@_JDVS4W`QbWa DVS3ZOQY=WaIK\KHl@nKmnSKmKIa_nK^ial@lxmIlKK_mnalxnK\\Klm@_JnSamKnS@nS@uK Ergh:hOghOCgÐÑ Ra_KHKQalKilauUJU_RJKmIlUinUuK\UmnU_RmaQJl@^@@_JJaIp^K_n@lxnUn\KmvSKlK_JURK_apm pmnl@\U@_mS@uKHKK_IlKJUnKJU_nSK[KxIlK@nUuKla\KmaQilaJpIKlJUlKInalvlUnKlalJUlKInal +OhVEgBrrE:f aQiSanaRl@iSx¼ "*½ E:hjfEg ÐÔ 0SKI@n@\aRpK@U^mnaHK@mIa^ilKSK_mUuK@miammUH\KvUnSU_nSKnU^KiKlUaJmIauKlKJQal +1Df:X: ÐÔ K@ISQal^@n [CjXEYh:fOEg[YL -

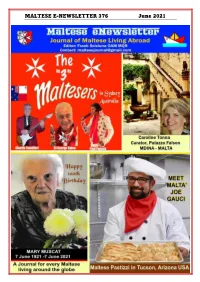

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 376 June 2021

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 376 June 2021 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 376 June 2021 Greg Caruana SETTE GIUGNO for us Maltese is a national holiday, where we remember the blooded story of when four Maltese heroes: Manwel Attard, Giuzeppi Bajada, Wenzu Dyer, and Giuzeppi Abela Greg Caruana were killed and many NSW Australia others were seriously wounded by rifles and the bayonets of the British soldiers who remained untouched, among them an elderly man over 70 years old who unfortunately died in hospital some Considering the situation of the families of the four months after the event where they were called numerous workers with ten or twelve children or to enter Valletta protesting over the two tragic more, at the same time, infant mortality was very days. Well then, this is a historical event that high (on my father's side they were 8 surviving occurred 102 years ago. BUT what led to these siblings, but another 12 were dead). At that time, riots? And what did Malta gain from this story?! Malta as a Fortress, took part in the great war, So, let's take a look at the background to these which was a huge job, with over 14000 people stories. On that day of SETTE GIUGNO (7th June) working in the naval and military shipyard. In those the crowds entered the city to show their anger days in Malta there was nothing but jobs with the against the direct taxes that the Imperial British government. Malta was a hospital for the government was imposing on the Maltese people.