The Soul-Hypothesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Meme Machine

spring books dimensions — the four dimensions of rela- zero) has always provoked the question of properties of replication, variation and tivistic space–time and six others of which whether spin is a property of particles or of competition is a “selfish replicator” that can we are unaware. Thus there is room for space. The materialization of particles from spread through populations by an analogue ample orthogonality to generate selection apparently empty space is similarly provok- of natural selection. Memes qualify as repli- rules that prevent bizarre happenings ing. String theory neatly answers them all. cators because bits of culture can be copied between particles. So what lies ahead? Not even Greene is by imitation and compete with other units The most persuasive part of Greene’s sure. String theory may not turn out to be for human attention. Thus, despite the dif- excellent book is that in which he persuades the cat’s whiskers he hopes. There are alter- ferences between memes and genes (genes, the reader that the problem of the six hidden natives, such as Roger Penrose’s twistor the- for example, are almost never passed to dimensions is not a problem but a matter of ory (which Greene reckons may say the same unrelated individuals), those memes most perspective. A garden hose seen from a great as strings). The most imaginative suggestion easily replicated and mimicked could prolif- distance looks like a one-dimensional object, in this imaginative book is that the time has erate, causing swift and important cultural but close up it is plainly a two-dimensional come to solve problems of quantum gravity change. -

Dennett's Theory of the Folk Theory of Consciousness

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Philsci-Archive Dennett’s Theory of the Folk Theory of Consciousness1 Justin Sytsma Abstract: It is not uncommon to find assumptions being made about folk psychology in the discussions of phenomenal consciousness in philosophy of mind. In this article I consider one example, focusing on what Dan Dennett says about the “folk theory of consciousness.” I show that he holds that the folk believe that qualities like colors that we are acquainted with in ordinary perception are phenomenal qualities. Nonetheless, the shape of the folk theory is an empirical matter and in the absence of empirical investigation there is ample room for doubt. Fortunately, experimental evidence on the topic is now being produced by experimental philosophers and psychologists. This article contributes to this growing literature, presenting the results of six new studies on the folk view of colors and pains. I argue that the results indicate against Dennett’s theory of the folk theory of consciousness. The existence of phenomenal consciousness is often taken for granted in the philosophical and scientific literature on the topic. Sometimes, this attitude is supported by claims that phenomenal consciousness is in some way evident in our ordinary experience itself.2 The prevalence of this attitude can also be seen in the way that some skeptics about phenomenal consciousness discuss the supposed phenomenon. For example, the qualia eliminativist Dan Dennett seems to accept that belief in qualia is part of our “folk theory of consciousness” (2005, 31). In contrast, I have argued that phenomenal consciousness is not evident in ordinary experience alone—that it is not phenomenologically obvious—and that this can be drawn out by 1 To appear in the Journal of Consciousness Studies. -

PHIL 306: Philosophy of Mind Introduction: Course Requirements: Materials

PHIL 306: Philosophy of Mind Fall 2016, MWF, 8:35—9:25, Currie 408/9 (Note: Conferences will replace the Friday lecture starting the week of Sep 12-16) Instructor: Robert Stephens Email: [email protected] Office: LEA916 Office hrs: Fridays 13:00-15:00, or by appointment Teaching assistants: Karina Vold Andre Martin [email protected] [email protected] Introduction: In this course, we will examine some of the major questions concerning the nature and functioning of the mind, as discussed in contemporary philosophy and cognitive science. What exactly is a mind? Where is it located? What is it composed of? How is it organized? How does it work? What are its limitations? We will look at a number of theories that attempt to answer various aspects of these questions, and we will zero in on a number of current philosophical debates that have grown out of and intertwined with these discussions. Some of the specific issues we will encounter include: o Is the mind something physical or not? Is my mind simply my brain? Or is it a product of my brain? Or is it something more than my physical brain? o Where does the mind fit into our scientific understanding of ourselves and our world? o What is the relationship between mind and behavior? How does mental causation work? o Do minds require brains? Or could there be many different sorts of minds? Artificial minds? o What is required for thinking? Language? Perception? Memory? Sensation? o Is the mind like a sort of computer? Or is that a misleading metaphor? o What are the different sorts of mental states? What characterizes and/or constitutes them? o What are concepts? How are they formed? How are they stored? How are they accessed? o How do we explain consciousness? Is consciousness necessarily subjective? o What role does the body play in the composition of mind? What about the environment? o What can delusions and other pathological mental states teach us about the nature of mind? Course Requirements: The reading load in this course is fairly demanding. -

Religion & Philosophy

Religion & Philosophy Books – General The Ego and the Id, Sigmund Freud Conscience: A Very Short Introduction, Paul Strohm On Liberty, J S Mill The Body and Society, Peter Brown Letters and Papers from Prison, Dietrich Bonhoeffer The Autobiography of Saint Teresa, Allison Peers Consciousness: An Introduction, Susan Blackmore The City of God, St Augustine The Concept of Mind, Gilbert Ryle Summa Theologiae, Aquinas The Blind Watchmaker, Richard Dawkins Natural Theology, Paley The Major Works, Anselm of Canterbury Books – Religion Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, David Christian Theology, Alister McGrath Hume A Theology: The Basics, Alister McGrath The Cost of Discipleship, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Books - Philosophy Jesus Through the Centuries, Jaroslav Pelikan An Introduction to Plato’s Republic, Julia Annas The Shadow of the Galilean, Gerd Theissen The Republic, Plato Humanae Vitae, Pope Paul VI Physics, Aristotle Issues in Human Sexuality, Church of England House of Bishops Metaphysics, Aristotle De Concordia, Anselm of Canterbury Principles of Philosophy, Rene Descartes The Coherence of Theism, Richard Swinburne Language, Truth and Logic, A J Ayer Principles of Christian Theology, John Macquarrie Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein Dynamics of Faith, Paul Tillich A Critique of Pure Reason, Kant Catechism of the Catholic Church Varieties of Religious Experience, William James Books – Philosophy of Religion Philosophy of Religion: A Guide and Anthology, Brian Davies God Talk is Evidently Nonsense, A J Ayer Consolation of Philosophy, -

The Science Studio with Daniel Dennett

The Science Studio With Daniel Dennett ROGER BINGHAM: My guest today in the Science Studio is Dan Dennett, who is the professor of philosophy and co-director for the Center For Cognitive Studies at Tufts University, co-founder and co-director of the Curricula Software Studio at Tufts, and he helped design museum exhibits on computers for the Smithsonian, the Museum of Science in Boston, and the Computer Museum in Boston. But more importantly he’s known as the author of many books, including most recently Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. So, Dan Dennett, let me just take you back to an interview, because this is Beyond Belief Two: Enlightenment 2.0. You were supposed to have been at the first meeting last year. There’s an interview that you did some time ago with our old friend, Susan Blackmore, where she asked you “I assume you don’t believe in God; do you think anything of the person survives physical death?” You got very close to physical death about a year ago. DANIEL DENNETT: I did, yeah. BINGHAM: Would you like to recount that wonderful experience? DENNETT: I had had a triple bypass in ‘99, but I was fine; I was in good shape. But then I had a so-called aortic dissection. My aorta, the main pipe from the heart up to the rest of the body, sort of blew out. It was held together by the scar tissue from the old operation; that’s what saved my life, first. And so I had that all replaced - I now have a Dacron aorta and a carbon fiber aortic valve, and I’m fine, as you can see. -

2006, in Science & Theology News Online, a Response to A

Science & Theology News http://www.stnews.org/print.php?article_id=2869 Daniel C. Dennett: Religion’s just a survival meme Daniel C. Dennett, director of Tufts University’s Center for Cognitive Studies, stands up for his book By Daniel C. Dennett (June 16, 2006) In his critique of my recent book, Breaking the Spell, Alister McGrath is pounding on an open door. Yes, of course, scientific ideas are memes and atheism is a meme. That’s not the point. The point is not to criticize anything by calling it a meme. On the contrary, it is to provide an explanatory basis. So, of course, psychologist and memeticist Susan Blackmore was right to say that atheism is a meme. How many of you readers think there are words? How many of you think that words are in your ontology? Do you believe in words, or are you not so sure that words exist? I think words exist, but if you think about them, they are extremely puzzling. What are they made of? They are not sounds. They’re not made of ink. It turns out that the concept of a word is abstract. They are so familiar to us that we don’t tend to realize how strange words are as a category. If you believe in words then you believe in memes because words are memes that can be pronounced. Then there are memes that can’t be pronounced, like fashions and other behaviors. And then there are large complexes of memes. The existence of memes is not in doubt at all. -

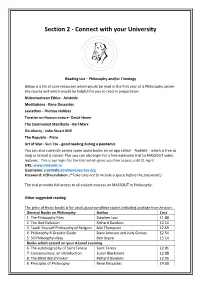

Section 2 - Connect with Your University

Section 2 - Connect with your University Reading List – Philosophy and/or Theology Below is a list of core resources which would be read in the first year of a Philosophy univer- sity course and which would be helpful for you to read in preparation: Nichomachean Ethics - Aristotle Meditations - Rene Descartes Leviathan - Thomas Hobbes Treatise on Human nature- David Hume The Communist Manifesto - Karl Marx On Liberty - John Stuart Mill The Republic - Plato Art of War - Sun Tzu - good reading during a pandemic You can also currently access some audio books on an app called - 'Audible' - which is free as long as School is closed. Plus you can also login for a free extended trial to MASSOLIT video lectures. This is our login for the trial which gives you free access until 31 April: URL: www.massolit.io Username: [email protected] Password: JCSFoundation (*Take care not to include a space before the password.) The trial provides full access to all subject courses on MASSOLIT in Philosophy. Other suggested reading The price of these books is for used, good condition copies including postage from Amazon: General Books on Philosophy Author Cost 1. The Philosophy Files Stephen Law £1.88 2. The God Delusion Richard Dawkins £2.14 3. Teach Yourself Philosophy of Religion Mel Thompson £2.69 4. Philosophy A Graphic Guide Dave Johnson and Judy Groves £2.54 5. 50 Philosophy Ideas Ben Dupre £5.14 Books which extend on your A Level Learning 6. The autobiography of Saint Teresa Saint Teresa £2.81 7. Consciousness; an introduction Susan Blackmore £2.88 8. -

Science and Near-Death Experience by Susan Blackmore

BOOK REVIEW Kenneth Ring, Ph.D. University of Connecticut Dying to Live: Science and Near-Death Experience, by Susan Blackmore. London, England: Grafton, 1993, 291 pp., 6.99 (Dis tributed in the United States by Prometheus Books, $23.95). Susan Blackmore is an English parapsychologist of skeptical lean ings who, thanks to this book and her frequent media appearances, is quickly becoming the critic near-death experience (NDE) lovers love to hate. And, as she herself has confessed (Blackmore, 1992), she fully expects many people to hate this book because it seeks to give a purely materialistic and reductive explanation for the NDE, and one that deprives it utterly of any implication of life after death. As a result of her provocative and uncompromising views and her interest to make them more widely known, Blackmore has cheerfully thrown herself into the unrewarding role of spoilsport at the NDErs' garden party, the Queen Skeptic on television talk shows and docu mentaries, and, not surprisingly, has lately made something of a ca reer as the combative heroine for such professionally debunking organizations as the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), on whose Executive Council she now sits. With opinions and affiliations like these, it would be un derstandable that persons sympathetic to the NDE and its spiritual import would be motivated either to avoid Blackmore's book in droves or, if they were to read it, to trash it unmercifully. Neither response, however, at least in my judgment, is warranted. This is a book that, like death itself, demands attention, and that offers not only a bracing challenge to persons interested in the NDE, Kenneth Ring, Ph.D., is Professor Emeritus of Psychology at the University of Con necticut. -

The Parallel Mind by Rana Zandi a Thesis Exhibition Presented To

The Parallel Mind By Rana Zandi A thesis exhibition presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Digital Futures April 2018 © Rana Zandi 2018 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. ii Rana Zandi, OCAD University, Parallel Mind, Master of Arts, Digital Futures, 2018 ABSTRACT Throughout the last century, Western scholars from various fields have contributed toward finding a general theory of consciousness that can accurately describe how the human brain processes information, and how it reflects and becomes aware of this information. In 2013, Michael Graziano an American scientist focused on the awareness aspect of consciousness and proposed the Attention Schema Theory of Consciousness (AST) to solve why the mind becomes aware in the first place. This thesis takes a stance that life on the screen has allowed us to extend our identities through embodiment of a second self in cyberspace. By using textual analysis, thought experiments, conceptual models, and mind activities, this work formulates parallel mind– as a self-aware digital entity that uses the content of the digital self. -

A Very Short Introduction by Susan Blackmore, Falls Into This Latter Camp

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 446–453, 2018 0892-3310/18 BOOK REVIEW Consciousness: A Very Short Introduction second edition by Susan Blackmore. Oxford University Press, 2018. 152 pp., $10.46 (paperback). ISBN: 978-0198794738. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31275/2018.1299 What is consciousness? What is this thing with which we are most intimate, yet remains outside of our best scientific understanding? In recent years, consciousness research has expanded its range of investigation, and these include new metaphysical approaches. However, we are still far from any kind of consensus on a theory of consciousness. In addition, scientists and philosophers remain divided on what a satisfactory theory or explanation might look like. Many are confident that consciousness will ultimately be explained through various materialistic processes that we do not yet understand. There are others who champion more radical approaches than more conventional, physicalist ones. Then there are those who insist that when we take the right approach, much of the mystery evaporates. Consciousness: A Very Short Introduction by Susan Blackmore, falls into this latter camp. The book does offer some attractive features. Blackmore uses an extremely bare bones approach to present a considerable range of information within its slender volume. Overall, her style is concise and engaging. She also provides many useful and interesting summaries on current work in neurobiology and cognitive science. That said, however, the book is flawed. As I’ll discuss, the book is far from a neutral and even-handed treatment for various theories of consciousness. Blackmore doesn’t waste much time before she begins to tilt the discussion toward her own view, which she calls delusionism. -

Fake News, a Construction of Reality

Fake news, a construction of reality »You can only find truth with logic, if you have already found truth without it.« G.K.Chesterton While we generally accept evolutionary mechanisms on the biological level, level of nature (gene interaction and replication), it seems that for human nature/nurture evolution rarely comes into play. Public relations research is especially prone to avoiding cross fertilization of not only natural sciences, but also evolutionary theory and philosophy in the wider sense of the term. It is one of the aims of this paper to point to various fields of knowledge that not only could but should serve as an important mental tool for any PR practitioner, not to mention researchers. Since we are confined to a memetic world, as it is going to be proven later, there are no obstacles for researchers of any field in understanding the findings from other fields from the (necessary) perspective limited by his so far acquired discourse. The main aim of this paper is to challenge the most widely accepted malicious nature and consequences of fake news. This paper does not limit fake news to media news, which were originally branded with that name, but to all instances of communication when some news/information is taken and defined as fake. It is not the purpose of this paper to go deeper into the genealogy of the term, which is interesting because fake is mostly assigned to opinion leaders. When public anonymous would say something that would be defined as fake if uttered by Donald Trump, we call this a lie. -

"Shakespeare and the 'Multiple-Drafts' Model of Consciousness" by Gabriel Egan

Egan, Gabriel. 2006g. 'Shakespeare and the 'Multiple-Drafts' Model of Consciousness': Paper delivered at the seminar 'The Possibility of Awareness' on 8 August at the 32th International Shakespeare Conference at the Shakespeare Institute, Stratford on Avon, 6-11 August "Shakespeare and the 'multiple-drafts' model of consciousness" by Gabriel Egan Preamble The following thoughts arise from a book that I am writing on the twentieth- century history of editorial theories in respect of Shakespeare. The New Bibliography that emerged from the work of A. J. Pollard, W. W. Greg, and R. B. McKerrow in the first decades of the century assumed a relatively unproblematic application of Platonic idealism for the relationship between the play as conceived in the mind of the dramatist and the play as performed or written down. Such idealism has in recent critical work (especially from the schools of New Historicism and Cultural Materialism) become decidedly unfashionable and associated with political conservatism. Coming to textual theory from the angle of Marxist ecocriticism, I wish to rehabilitate Platonic idealism as a reasonable way to unite progressive literary scholarship with the latest work in cognitive science. As any materialist must accept, ideas have a basis in the organization of matter in the human mind--ideas are to that extent physically real--and the new scientific studies of consciousness (especially memetics and the 'multiple- drafts' model of cognition) show that the Platonic analogy provides a good way to conceptualize the distinction between the play as abstract thought and its various extant physical embodiments in manuscript and print textualisations. * Theories of Mind Twentieth-century thinking on the nature of the mind has been notably resistant to unity.