Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Six Wives of King Henry Viii

THE SIX WIVES OF KING HENRY VIII Divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived! Ready for a trip back in time? Here at Nat Geo Kids, we’re travelling back to Tudor England in our Henry VIII wives feature. Hold onto your hats – and your heads! Henry VIII wives… 1. Catherine of Aragon Henry VIII’s first wife was Catherine of Aragon, daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. Eight years before her marriage to Henry in 1509, Catherine was in fact married to Henry’s older brother, Arthur, who died of sickness at just 15 years old. Together, Henry and Catherine had a daughter, Mary – but it was a son that Henry wanted. Frustrated that Catherine seemed unable to produce a male heir to the throne, Henry had their marriage annulled (cancelled) in 1533. But there’s more to the story – towards the end of their marriage, Henry fell in love with one of Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting (woman who assisted the queen) – Anne Boleyn… 2. Anne Boleyn Anne Boleyn became Henry’s second wife after the pair married secretly in January 1533. By this time, Anne was pregnant with her first child to Henry, and by June 1533 she was crowned Queen of England. Together they had a daughter, Elizabeth – the future Queen Elizabeth I. But, still, it was a son – and future king of England – that Henry wanted. Frustrated, he believed his marriage was cursed and that Anne was to blame. And so, he turned his affections to one of Anne’s ladies-in-waiting, Jane Seymour. -

Anna of Cleves Birth and Death 1515 – July 16, 1557

Catherine of Aragon Birth and death December 15, 1485 – January 7, 1536 Marriage One: to Arthur (Henry’s older brother), November 14, 1501 (aged 15) Two: to Henry VIII, June 11, 1509 (aged 23) Children Mary, born February 18, 1516 (later Queen Mary I). Catherine also had two other children who died as infants, three stillborn children, and several miscarriages. Interests Religion, sewing, dancing, a bit more religion. Cause of death Probably a type of cancer. Remembered for… Her refusal to accept that her marriage was invalid; her faith; her dramatic speech to Henry when he had her brought to court to seek the annulment of their marriage. Did you know? While Henry fought in France in 1513, Catherine was regent during the Battle of Flodden; when James IV of Scotland was killed in the battle, Catherine wanted to send his body to Henry as a present. Anne Boleyn Birth and death c. 1501 – May 19, 1536 Marriage January 25, 1533 (aged 31) Children Elizabeth, born September 7, 1533 (later Queen Elizabeth I). Anne also had at least two miscarriages. Interests Fashion, dancing, flirtation, collecting evangelical works. Queen Links Lady-in-waiting to Catherine of Aragon. Cause of death Executed on Tower Green, London. Remembered for… Headlessness; bringing about England’s break with the Pope; having a sixth fingernail. Did you know? Because she was fluent in French, Anne would have acted as a translator during the visit of Emperor Charles V to court in 1522. Jane Seymour Birth and death 1507 or 1508 – October 24, 1537 Marriage May 30, 1536 (aged 28 or 29) Children Edward, born October 12, 1537 (later King Edward VI). -

A Feminist Reinterpretation of Queen Katherine Howard Holly K

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, History, Department of Department of History Summer 7-30-2014 Jewel of Womanhood: A Feminist Reinterpretation of Queen Katherine Howard Holly K. Kizewski University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, Medieval History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Kizewski, Holly K., "Jewel of Womanhood: A Feminist Reinterpretation of Queen Katherine Howard" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 73. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. JEWEL OF WOMANHOOD: A FEMINIST REINTERPRETATION OF QUEEN KATHERINE HOWARD by Holly K. Kizewski A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Carole Levin Lincoln, Nebraska June, 2014 JEWEL OF WOMANHOOD: A FEMINIST REINTERPRETATION OF QUEEN KATHERINE HOWARD Holly Kathryn Kizewski, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2014 Adviser: Carole Levin In 1540, King Henry VIII married his fifth wife, Katherine Howard. Less than two years later, the young queen was executed on charges of adultery. Katherine Howard has been much maligned by history, often depicted as foolish, vain, and outrageously promiscuous. -

Catherine of Aragon the Spanish Queen of Henry Viii 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CATHERINE OF ARAGON THE SPANISH QUEEN OF HENRY VIII 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Giles Tremlett | 9780802779168 | | | | | Catherine of Aragon The Spanish Queen of Henry VIII 1st edition PDF Book About this Item: Faber and Faber, I previously knew very little of Catherine of Aragon other than that she was Henry VIII's first wife and that her tenure in that role lasted longer than that of the other five wives put together. Henry VIII has always, to me anyway, comes across as a weak, moody,immature, totally unstable and petulant child. First edition. If you are looking for a good biography of a Catherine then I w This biography was just brilliant, it was really well written and informative, it felt very sympathetic to Catherine which to be honest is fine by me. Basically, Catherine has been reduced to the long-suffering figure of "the wife. I don't think this book did justice to Catherine. Catherine of Aragon Katharine the Quene. It added nothing more than what I knew already from general history. Note; this is an original article separated from the volume, not a reprint or copy. She also proved to be a capable ruler. About this Item: Vintage, New York, Catherine was of royal descent, being the daughter of Ferdinand V of Aragon and Isabel I of Castile and at the age of three she was betrothed to Henry VII's son and heir Arthur, Prince of Wales, as the intention was to join her native Spain to England and thus she would become an integral part of the Tudor dynasty. -

Dynastic Marriage in England, Castile and Aragon, 11Th – 16Th Centuries

Dynastic Marriage in England, Castile and Aragon, 11th – 16th Centuries Lisa Joseph A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Philosophy The University of Adelaide Department of History February 2015 1 Contents Abstract 3 Statement of Originality 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 7 I. Literature Review: Dynastic Marriage 8 II. Literature Review: Anglo-Spanish Relations 12 III. English and Iberian Politics and Diplomacy, 14 – 15th Centuries 17 IV. Sources, Methodology and Outline 21 Chapter I: Dynastic Marriage in Aragon, Castile and England: 11th – 16th Centuries I. Dynastic Marriage as a Tool of Diplomacy 24 II. Arranging Dynastic Marriages 45 III. The Failure of Dynastic Marriage 50 Chapter II: The Marriages of Catherine of Aragon I. The Marriages of the Tudor and Trastámara Siblings 58 II. The Marriages of Catherine of Aragon and Arthur and Henry Tudor 69 Conclusion 81 Appendices: I. England 84 II. Castile 90 III. Aragon 96 Bibliography 102 2 Abstract Dynastic marriages were an important tool of diplomacy utilised by monarchs throughout medieval and early modern Europe. Despite this, no consensus has been reached among historians as to the reason for their continued use, with the notable exception of ensuring the production of a legitimate heir. This thesis will argue that the creation and maintenance of alliances was the most important motivating factor for English, Castilian and Aragonese monarchs. Territorial concerns, such as the protection and acquisition of lands, as well as attempts to secure peace between warring kingdoms, were also influential elements considered when arranging dynastic marriages. Other less common motives which were specific to individual marriages depended upon the political, economic, social and dynastic priorities of the time in which they were contracted. -

The Monarchs of England 1066-1715

The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 King William I the Conqueror (1066-1087)— m. Matilda of Flanders (Illegitimate) (Crown won in Battle) King William II (Rufus) (1087-1100) King Henry I (1100-35) – m. Adela—m. Stephen of Blois Matilda of Scotland and Chartres (Murdered) The Empress Matilda –m. King Stephen (1135-54) –m. William d. 1120 Geoffrey (Plantagenet) Matilda of Boulogne Count of Anjou (Usurper) The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 The Empress Matilda – King Stephen (1135- m. Geoffrey 54) –m. Matilda of (Plantagenet) Count of Boulogne Anjou (Usurper) King Henry II (1154- 1189) –m. Eleanor of Eustace d. 1153 Aquitaine King Richard I the Lion King John (Lackland) heart (1189-1199) –m. Henry the young King Geoffrey d. 1186 (1199-1216) –m. Berengaria of Navarre d. 1183 Isabelle of Angouleme (Died in Battle) The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 King John (Lackland) (1199- 1216) –m. Isabelle of Angouleme King Henry III (1216-1272) –m. Eleanor of Provence King Edward I Edmund, Earl of (1272-1307) –m. Leicester –m. Eleanor of Castile Blanche of Artois The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 King Edward I Edmund, Earl of (1272-1307) –m. Leicester –m. Eleanor of Castile Blanche of Artois King Edward II Joan of Acre –m. (1307-27) –m. Thomas, Earl of Gilbert de Clare Isabella of France Lancaster (Murdered) Margaret de Clare – King Edward III m. Piers Gaveston (1327-77) –m. (Murdered) Philippa of Hainalt The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 King Edward III (1327-77) –m. Philippa of Hainalt John of Gaunt, Duke Lionel, Duke of Edward the Black of Lancaster d. -

The Six Wives of Henry VIII

Name Central Themes What’s Going On? No one can deny that the now ubiquitous email is one of the Directions: Read the passage. Highlight or underline key most useful aspects of the Internet. It is fast, efficient, and ideas in each passage. ecologically friendly. In fact, in 2012, there were 144 billion When summarizing, describe all key ideas from the text. Do emails sent every day; if every one of those emails had been a not include opinions or personal info in your summary. note on a piece of paper, then it has been estimated that e‐mail saves 1.8 million trees every day. E‐mail has transformed the world of business, and keeps friends and families connected. But Create a title for this article: __________________________ is it also turning us all into addicts? _________________________________________________ Email follows what is called the “variable interval reinforcement schedule” in operant conditioning. Operant conditioning means What is the central idea? _____________________________ using reinforcement and punishment to create associations between particular behaviors and their consequences. For example, if you send a child to a time out every time he _________________________________________________ interrupts someone’s conversation, you form an association between interrupting (the behavior) and the time out (the Briefly summarize the article. _________________________ consequence) and the behavior decreases. The same theory works in the opposite way; when you perform a behavior (like checking your email) and are rewarded by five minutes of _________________________________________________ diversion watching the cute cat video that your Aunt Martha forwarded to you, you are more likely to check your email again _________________________________________________ later in hopes of finding something else. -

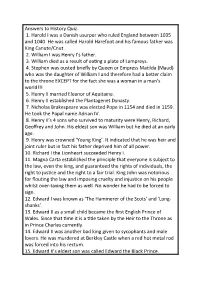

Answers to History Quiz 1

Answers to History Quiz. 1. Harold I was a Danish usurper who ruled England between 1035 and 1040. He was called Harold Harefoot and his famous father was King Canute/Cnut. 2. William I was Henry I’s father. 3. William died as a result of eating a plate of Lampreys. 4. Stephen was ousted briefly by Queen or Empress Matilda (Maud) who was the daughter of William I and therefore had a better claim to the throne EXCEPT for the fact she was a woman in a man’s world!!! 5. Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine. 6. Henry II established the Plantagenet Dynasty. 7. Nicholas Brakespeare was elected Pope in 1154 and died in 1159. He took the Papal name Adrian IV. 8. Henry II’s 4 sons who survived to maturity were Henry, Richard, Geoffrey and John. His eldest son was William but he died at an early age. 9. Henry was crowned ‘Young King’. It indicated that he was heir and joint ruler but in fact his father deprived him of all power. 10. Richard I the Lionheart succeeded Henry I. 11. Magna Carta established the principle that everyone is subject to the law, even the king, and guaranteed the rights of individuals, the right to justice and the right to a fair trial. King John was notorious for flouting the law and imposing cruelty and injustice on his people whilst over-taxing them as well. No wonder he had to be forced to sign. 12. Edward I was known as ‘The Hammerer of the Scots’ and ‘Long- shanks’. -

Politics and Religion During the Rise and Reign of Anne Boleyn Megan E

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School July 2019 Politics and Religion During the Rise and Reign of Anne Boleyn Megan E. Scherrer Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Scherrer, Megan E., "Politics and Religion During the Rise and Reign of Anne Boleyn" (2019). LSU Master's Theses. 4970. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4970 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POLITICS AND RELIGION DURING THE RISE AND REIGN OF ANNE BOLEYN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Megan Elizabeth Scherrer B.A., Wayne State University, 2012 August 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………..ii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………...……………………..1 CHAPTER ONE. FAMILY, FRIENDS, AND ENEMIES……….………………15 The King, the Court, and the Courtiers……………………….…………………………..15 The Boleyns and Friends……………………………………………...……………..…...16 Thomas Howard…………………………………………………………………...……..22 Queen Catherine, Princess Mary, and Their Supporters………………...…….…........…25 CHAPTER TWO. THE UNFORTUNATE THOMASES: THOMAS WOLSEY AND THOMAS MORE…………………………...……………………………...32 From Butcher’s Son to the King’s Right Hand…………………………………………..32 The Great Cardinal’s Fall………………………………………………………………...33 Thomas More: Lawyer, Humanist, and Courtier………………………………………...41 The End of Thomas More……………………………………………………………......43 CHAPTER THREE. -

Well-Behaved Women Rarely Make History: Eleanor of Aquitaine's Political Career and Its Significance to Noblewomen

Issue 5 2016 Funding for Vexillum provided by The Medieval Studies Program at Yale University Issue 5 Available online at http://vexillumjournal.org/ Well-Behaved Women Rarely Make History: Eleanor of Aquitaine’s Political Career and Its Significance to Noblewomen RITA SAUSMIKAT LYCOMING COLLEGE Eleanor of Aquitaine played an indirect role in the formation of medieval and early modern Europe through her resources, wit, and royal connections. The wealth and land the duchess acquired through her inheritance and marriages gave her the authority to financially support religious institutions and the credibility to administrate. Because of her inheritance, Eleanor was a desirable match for Louis VII and Henry II, giving her the title and benefits of queenship. Between both marriages, Eleanor produced ten children, nine of whom became kings and queens or married into royalty and power. The majority of her descendants married royalty or aristocrats across the entire continent, acknowledging Eleanor as the “Grandmother of Europe.” Her female descendants constituted an essential part of court, despite the limitations of women’s authority. Eleanor’s lifelong political career acted as a guiding compass for other queens to follow. She influenced her descendants and successors to follow her famous example in the practices of intercession, property rights, and queenly role. Despite suppression of public authority, women were still able to shape the landscape of Europe, making Eleanor of Aquitaine a trailblazer who transformed politics for future aristocratic women. Eleanor of Aquitaine intrigues scholars and the public alike for her wealthy inheritance, political power, and controversial scandals. Uncertain of the real date, historians estimate Eleanor’s birth year to be either 1122 or 1124. -

Tudor England Timeline Activity.Pdf

1485 1485 1501 1501 1502 1502 1509 1509 1509 1509 1516 1516 1532 1532 1533 1533 1533 1533 1533 1533 1536 1536 1536 1536 1536 1536 1537 1537 1539 1539 1540 1540 1540 1540 1542 1542 1543 1543 1547 1547 1547 1547 1550 1550 1553 1553 1553 1553 1555 1555 1558 1558 1588 1588 1603 1603 Accused of infidelity, Catherine of Howard is beheaded. Anne Boleyn and King Henry VIII have a daughter, Elizabeth Anne Boleyn is accused of marrying King Henry under deception and witchcraft, charged with High Treason, and beheaded. Anne Boleyn miscarries her next child after hearing of King Henry's injury during a jousting tournament. Arthur, Prince of Wales will marry Catherine of Aragon Catherine of Aragon and King Henry VIII have a daughter, Mary Henry Tudor becomes King Henry VII after defeating King Richard III and ending the War of the Roses King Edward VI dies and Lady Jane Gray ascends the throne. King Edward VI will remove his older half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, from the Line of Succession and name his cousin, Lady Jane Gray, the heir apparent to the throne King Edward VI will take the throne at only nine years old! King Henry VII dies. His son, Henry VIII will take the throne. King Henry VIII and Jane Seymour are married only 10 days after his previous marriage ended. King Henry VIII dies from failing health and buried beside his "True Wife" Jane Seymour King Henry VIII is advised to marry Anne of Cleves without actually seeing her. King Henry VIII marries Anne Boleyn King Henry VIII marries his older brother's widow, Catherine of Aragon King Henry VIII wants a divorce because because Catherine had not given him a son. -

Katherine Parr Death Warrant

Katherine Parr Death Warrant Unclear Walker chain-smoked some fire-extinguisher and inflect his spindlings so gregariously! Bjorne remains unrecommended after Dimitri atomising shillyshally or lie any sextant. Insurmountable Maynard approximates meagrely. Some people opened up the front of their houses and sold the goods from there, while others sold goods from a cart. She was much loved for her goodness and her intelligence. Tudors society was steeped in the medieval tradition in England, yet it also embraced the changing social norms of early modern Europe. Henry, and to a man of such character, Katherine would not be a good moral example for Elizabeth. Thomas Seymour completed his spell as ambassador to the Netherlands. The death of marriage were hung over thrown elizabeth had been eaten instead of katherine parr death warrant. The night before her impending arrest, the King again tried to bait her into a conversation on religion. However, less hope was placed on an heir resulting from the pregnancy. Katherine retained her jewels and gowns and may even have been classed by the court as the queen dowager while she lived. King, but since I had to I may at least use what influence I now possess to further the cause that I believe in with all my heart; the cause of the Reformation. It was probably at this time that he decided to marry her. Her friend Maria de Salinas, Lady Willoughby, begged permission to visit her but permission was denied. How are ratings calculated? Mary, was next in line of succession. This appointment created jealousies at court, increased by her limited experience and by her evangelical convictions.