The Established and the Outsiders: a Relational Analysis of Political Representations in the Trilogy Shrek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek the Musical Study Guide

The contents of this study guide are based on the National Educational Technology Standards for Teachers. Navigational Tools within this Study Guide Backward Forward Return to the Table of Contents Many pages contain a variety of external video links designed to enhance the content and the lessons. To view, click on the Magic Mirror. 2 SYNOPSIS USING THE LESSONS RESOURCES AND CREDITS TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 BEHIND THE SCENES – The Making of Shrek The Musical Section 2 LET YOUR FREAK FLAG FLY Section 2 Lessons Section 3 THE PRINCE AND THE POWER Section 3 Lessons Section 4 A FAIRY TALE FOR A NEW GENERATION Section 4 Lessons Section 5 IT ENDS HERE! - THE POWER OF PROTEST Section 5 Lessons 3 Act I Once Upon A Time. .there was a little ogre named Shrek whose parents sat him down to tell him what all little ogres are lovingly told on their seventh birthday – go away, and don’t come back. That’s right, all ogres are destined to live lonely, miserable lives being chased by torch-wielding mobs who want to kill them. So the young Shrek set off, and eventually found a patch of swampland far away from the world that despised him. Many years pass, and the little ogre grows into a very big ogre, who has learned to love the solitude and privacy of his wonderfully stinky swamp (Big Bright Beautiful World.) Unfortunately, Shrek’s quiet little life is turned upside down when a pack of distraught Fairy Tale Creatures are dumped on his precious land. Pinocchio and his ragtag crew of pigs, witches and bears, lament their sorry fate, and explain that they’ve been banished from the Kingdom of Duloc by the evil Lord Farquaad for being freakishly different from everyone else (Story Of My Life.) Left with no choice, the grumpy ogre sets off left to right Jacob Ming-Trent to give that egotistical zealot a piece of his mind, and to Adam Riegler hopefully get his swamp back, exactly as it was. -

SHREK the MUSICAL Official Broadway Study Guide CONTENTS

WRITTEN BY MARK PALMER DIRECTOR OF LEARNING, CREATIVE AND MEDIA WIldERN SCHOOL, SOUTHAMPTON WITH AddITIONAL MATERIAL BY MICHAEL NAYLOR AND SUE MACCIA FROM SHREK THE MUSICAL OFFICIAL BROADWAY STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Welcome to the SHREK THE MUSICAL Education Pack! A SHREK CHRONOLOGY 4 A timeline of the development of Shrek from book to film to musical. SynoPsis 5 A summary of the events of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Production 6 Interviews with members of the creative team of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Fairy Tales 8 An opportunity for students to explore the genre of Fairy Tales. Feelings 9 Exploring some of the hang-ups of characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. let your Freak flag fly 10 Opportunities for students to consider the themes and characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. One-UPmanshiP 11 Activities that explore the idea of exaggerated claims and counter-claims. PoWer 12 Activities that encourage students to be able to argue both sides of a controversial topic. CamPaign 13 Exploring the concept of campaigning and the elements that make a campaign successful. Categories 14 Activities that explore the segregation of different groups of people. Difference 15 Exploring and celebrating differences in the classroom. Protest 16 Looking at historical protesters and the way that they made their voices heard. AccePtance 17 Learning to accept ourselves and each other as we are. FURTHER INFORMATION 18 Books, CD’s, DVD’s and web links to help in your teaching of SHREK THE MUSICAL. ResourceS 19 Photocopiable resources repeated here. INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Education Pack for SHREK THE MUSICAL! Increasingly movies are inspiring West End and Broadway shows, and the Shrek series, based on the William Steig book, already has four feature films, two Christmas specials, a Halloween special and 4D special, in theme parks around the world under its belt. -

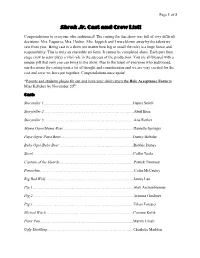

Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List!

Page 1 of 3 Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List! Congratulations to everyone who auditioned! The casting for this show was full of very difficult decisions. Mrs. Esquerra, Mrs. Hosker, Mrs. Joppich and I were blown away by the talent we saw from you. Being cast in a show (no matter how big or small the role) is a huge honor and responsibility. This is truly an ensemble art form. It cannot be completed alone. Each part from stage crew to actor plays a vital role in the success of the production. You are all blessed with a unique gift that only you can bring to the show. Due to the talent of everyone who auditioned, our decisions for casting took a lot of thought and consideration and we are very excited for the cast and crew we have put together. Congratulations once again! *Parents and students please fill out and have your child return the Role Acceptance Form to Miss Kelleher by November 20th. Cast: Storyteller 1……………………………………………………….…..Hanna Smith Storyteller 2………………………………………………………...….Abril Brea Storyteller 3……………………………..……………………..………Ana Rother Mama Ogre/Mama Bear………………………….………………...…Danielle Springer Papa Ogre/ Papa Bear……………………………………………..…Danny Boboltz Baby Ogre/Baby Bear ………………………………...…….………...Robbie Dubay Shrek…………………………………………………………….....….Collin Toole Captain of the Guards………………………………………….…...…Patrick Twomey Pinocchio……………………………………………………………....Colin McCauley Big Bad Wolf………………………………………………….….…....James Lau Pig 1……………………………………………………………….......Alex Aschenbrenner Pig 2…………………………………………………………….…......Arianna Gardiner Pig 3………………………………………………………….......……Ethan -

Shrek Audition Monologues

Shrek Audition Monologues Shrek: Once upon a time there was a little ogre named Shrek, who lived with his parents in a bog by a tree. It was a pretty nasty place, but he was happy because ogres like nasty. On his 7th birthday the little ogre’s parents sat him down to talk, just as all ogre parents had for hundreds of years before. Ahh, I know it’s sad, very sad, but ogres are used to that – the hardships, the indignities. And so the little ogre went on his way and found a perfectly rancid swamp far away from civilization. And whenever a mob came along to attack him he knew exactly what to do. Rooooooaaaaar! Hahahaha! Fiona: Oh hello! Sorry I’m late! Welcome to Fiona: the Musical! Yay, let’s talk about me. Once upon a time, there was a little princess named Fiona, who lived in a Kingdom far, far away. One fateful day, her parents told her that it was time for her to be locked away in a desolate tower, guarded by a fire-breathing dragon- as so many princesses had for hundreds of years before. Isn’t that the saddest thing you’ve ever heard? A poor little princess hidden away from the world, high in a tower, awaiting her one true love Pinocchio: (Kid or teen) This place is a dump! Yeah, yeah I read Lord Farquaad’s decree. “ All fairytale characters have been banished from the kingdom of Duloc. All fruitcakes and freaks will be sent to a resettlement facility.” Did that guard just say “Pinocchio the puppet”? I’m not a puppet, I’m a real boy! Man, I tell ya, sometimes being a fairytale creature sucks pine-sap! Settle in, everyone. -

Shrek the Musical Cast List

Shrek the Musical Fairy Tale Creatures Cast List Gingy – Adelia Haines Pinocchio – Logan Overturf Big Bad Wolf – Zach Abrams Shrek – James Long Shrek Understudy – Blake Brinsa Three Little Pigs Briksi - Ziona Patterson Youngest Fiona – Straw Baby - Emi Scarlett Abby Zimmerman Styx - Josie Hougham Teen Fiona – Kaylee Peraza Princess Fiona – Miyon Roston White Rabbit – Erica Burnett Ogress Fiona – Fairy Godmother – Sadie Waggerman Madison Bogart Peter Pan – DeSean Harrison Donkey – Jordon Prince Wicked Witch – Aarika Wilson Donkey Understudy – Sugar Plum Fairy – Zach Abrams Madison Coonce Tooth Fairy – Abby Dixon Lord Farquaad – Kyle Villaverde Ugly Duckling – Paige Hutson Lord Farquaad Understudy – Blake Brinsa/Zach Abrams Three Bears Papa Bear - Blake Brinsa Mama Bear – Audrey Resch Dragon – Alyna Mathews Baby Bear - Hunter Murray Dragon Understudy – Madison Coonce Mad Hatter – Derek Walsh Dragonettes Humpty Dumpty - Brimstone – Audrey Resch Quincy Knighten Smokey - Madison Coonce Humpty Dumpty Understudy - Ashley Summers Elf – Makayla Gandara Dwarf – Julien Harrison Three Blind Mice Captain Thelonius – 1. Kristina King Jadin Douglas 2. Alexis Baynon Duloc Guards 3. Molly Bryant 1. Julian Harrison 2. Quincy Jackson Bluebird – Kaylee Peraza 3. Donovan Ortiz 4. Adrian Craigmiles Bishop – Adrian Craigmiles Knights Little Shrek – Liam White 1. Israel Aguilar Mama Ogre – 2. Hunter Murray Delaney Bresnahan 3. Drake Zion Papa Ogre – Tyler Freeman 4. Jadin Douglas King Harold – Donovan Ortiz Queen Lillian – Pied Piper – Rusty Lasiter Sadie Waggerman Pied Piper’s Rats 1. Jaelee Pittel 2. Gavin Davis 3. Bella Rodriguez 4. Natalie Bryant 5. Julian Harrison 6. Kristina King 7. Elva Rodriguez 8. Quincy Jackson Angry Mob Happy People Natalie Bryant Marissa Pendergrast Julien Harrison Drake Zion Cara Emerson Hannah Schoonover Sam Littlecreek Angelina Hess Kristina King Ashley Summers Duloc Performers 1. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE For Immediate Release DATE: September 2016 CONTACT: Kori Radloff, [email protected], 402-502-4641 The Rose Theater announces the cast of Shrek The Musical Robby Stone Nik Whitcomb Lauren Krupski Brian Guehring Sue Gillespie Booton Colleen Kilcoyne Shrek Donkey Fiona Lord Farquaad Dragon Gingy (OMAHA, Nebr.) An ornery ogre, a peculiar princess, a talking donkey, a vertically- challenged villain and a love struck dragon are headed to The Rose Theater with the production of Shrek The Musical. The Broadway sensation, based on DreamWorks Animation’s 2001 blockbuster Shrek will run at The Rose, Sept. 30 through Oct. 15, 2016. The Rose is proud to announce the cast of Shrek The Musical. The cast consists of several Rose Theater favorites. Robby Stone (Honk, Peter & the Starcatcher, Big Nate, Jackie & Me) will bring the green ogre to life. Nik Whitcomb (Pete the Cat, Sherlock Holmes & the First Baker Street Irregular, Honk) plays Shrek’s sidekick Donkey. Princess Fiona will be played by Lauren Krupski (Cat in the Hat, Pete the Cat, A Christmas Story). Three Rose teaching artists will also be featured on stage: Brian Guehring (Robin Hood, Honk, Mary Poppins) as Lord Farquaad, Sue Gillespie Booton (Pete the Cat, Cat in the Hat) as Dragon, and Colleen Kilcoyne (Honk) as Gingy. Rounding out the adult cast are Jennifer Castello and Regina Palmer. Of special note, the cast includes several alumni and current participants of The Rose’s Teens ‘N’ Theater program. Shrek The Musical also features 12 youth performers who will share various roles throughout the show. = MORE = The Rose Theater t (402) 345-4849 2001 Farnam Street f (402) 344-7255 Omaha, NE 68102 www.rosetheater.org The Rose Theater announces Shrek cast Page 2 of 3 Contact: Kori Radloff, 402-502-4641 Shrek The Musical is based on the popular DreamWorks Animation movie. -

Audition Pack.Pages

COFFS HARBOUR MUSICAL COMEDY COMPANY AUDITIONS FOR SHREK Date: Saturday 12th and Sunday 13th January, 2019 Call backs: Monday 14th January, 7pm Venue: "O" Block Theatre, CHEC Campus, Hogbin Drive, Coffs Harbour Time: 09:30 for registration, 10am start. PRODUCER: Coffs Harbour Musical Comedy Company DIRECTOR & CHOREOGRAPHER: Donna Fairall 0411 116471 MUSIC DIRECTOR: Tim Egan 0418 515617 PERFORMANCE DATES: 4-26 May, 2019 5 shows a week: Weds, Fri, Sat evenings, plus a matinee on Saturdays and Sundays. There will be an extra show on Thursday May 23rd, making 18 performances in all. REHEARSALS: Monday & Wednesday evenings, & Sunday afternoons, CHEC Campus FIRST REHEARSAL: Sunday January 20th CONTACT CHMCC: [email protected] A recording of ‘Shrek the Musical’ is widely available on DVD and YouTube. CHARACTERS AND VOCAL RANGES Shrek - An ogre who has spent most of his life as an outcast, living in a swamp far from civilization; his brutish exterior disguises a soulful and brave heart. A reluctant hero. Powerful presence with great wit. Ability to produce a credible Scottish accent a bonus. Actor: male 25yrs-adult Vocal Range: high baritone/tenor A2 – G#4 Princess Fiona - The beautiful princess of Far Far Away, she transforms into an ogre every night when the sun sets. Rescued by Shrek, she has spent most of her life locked in a dragon-guarded castle reading romantic fairy tales. Not your typical fairytale princess, she is smart and outspoken. And belches. Actor: female 25yrs-adult Vocal Range: alto/soprano with high belt F3 - G6 Donkey - Shrek’s self-appointed side-kick, as charming as he is clingy, a bright-eyed motor- mouth whose eagerness and quick wit barely disguise his desperate need for a friend. -

International Viewbook

TO BE THE BEST, TRAIN WITH THE BEST! For more than 50 years, AMDA has been devoted to training the actor, singer and dancer for stage, film and television. AMDA has launched some of the most successful global careers of performers in theatre, film, television and dance. That’s because aspiring actors, singers and dancers from all over the world receive world-class training at AMDA. AMDA has two campuses—one in each of the entertainment capitals of the world: Los Angeles and New York City. AMDA College of the Performing Arts, located in the heart of Hollywood, offers Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) and Associate of Occupational Studies (AOS) degrees. The American Musical and Dramatic Academy, located in the prestigious Upper West Side of Manhattan, offers professional certificate programs with an option to apply to the AMDA Los Angeles campus to complete a BFA degree. 1 AMDA Facts and Figures Founded in 1964 as a musical theatre school emerging from the vibrant Manhattan arts scene in New York City Opened its Los Angeles campus located in the heart of Hollywood in 2003 A private, nonprofit institution of higher education Accredited by the National Association of Schools of Theatre (NAST) and licensed to operate by the states of New York and California Ranked #4 on Playbill Magazine’s list of colleges with the greatest number of graduates on Broadway in the 2018-19 season and #6 on the Niche.com list of Best Colleges for Performing Arts in America Four distinct BFA degree programs, three AOS degree programs, and three professional conservatory certificate programs allow students to choose their paths to success in the performing arts Partial financial support to approximately 95% of enrolled students, including international students Two Great Locations - New York City and Los Angeles are two of the most culturally and ethnically diverse cities in the United States. -

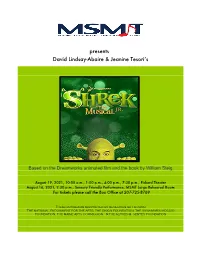

Shrek Study Guide2021

presents David Lindsay-Abaire & Jeanine Tesori’s Based on the Dreamworks animated film and the book by William Steig August 19, 2021, 10:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., 4:00 p.m., 7:30 p.m., Pickard Theater August 16, 2021, 2:30 p.m., Sensory Friendly Performance, MSMT Large Rehearsal Room For tickets please call the Box Office at 207-725-8769 These programs supported by generous gifts from The national endowment for the arts, the onion foundation, the anna-maria moggio foundation, the maine arts commission, & the alfred m. senter foundation 2 STUDY MATERIALS THE SOURCE MATERIAL Page 3 The Book by William Steig The Animated Film THE LINDSAY-ABAIRE & TESORI MUSICAL VERSION 4 Synopsis of Shrek The Musical TYA Version The Characters in Shrek: The Musical The Songs in Shrek: The Musical The Themes The Creators LINKS 10 On the Web ACTIVITIES 11 Discussion Questions after the Performance Play Mad Libs Write Your Own Story or Create Your Own Drawing Send Us Your Comments Color This Picture 3 THE SOURCE MATERIAL The Book by William Steig Shrek! is a humorous children's book published in 1990 by American book writer and cartoonist William Steig, about a repugnant, monstrous green creature who leaves home to see the world and ends up saving a princess. The name "Shrek" derives from the German Schreck and meaning "fear" or "fright.” The book served as the basis for the first Shrek movie and the popular Shrek film series over a decade after its publication. Synopsis of Steig’s Story Shrek is a repugnant, green-skinned, fire-breathing, seemingly indestructible monster who enjoys causing misery with his repulsiveness. -

Dawn Oesch Musical Director

Announcing Open Auditions for our October production of Music by Jeanine Tesori Book and Lyrics by David Lindsay-Abaire Based on the DreamWorks Motion Picture Director: Dawn Oesch Musical Director: Carol Hawks Choreographer: Melissa Lacijan When: Auditions: Tuesday , May 17 th and Wedne sday, May 18 th – 6:30pm to 8:30pm Callbacks: Thursday, May 19 th - evening Where: The Spa Little Theater, Saratoga Spa State Park For the audition: • Please prepare a 16-bar excerpt from a song of your choice. Upbeat songs only, no ballads. Selections from the show are allowed. • Please bring your own sheet music, as a pianist will be provided. No a capella singing. • Please bring a current photo & resume. Photos cannot be returned. • Dance auditions will be at callbacks. Please wear comfortable clothing and appropriate shoes. SHREK THE MUSICAL Set in a mythical “once upon a time” sort of land, Shrek The Musical is the story of a hulking green ogre who, after being mocked and feared his entire life by anything that crosses his path, retreats to an ugly green swamp to exist in happy isolation. Suddenly, a gang of homeless fairy-tale characters (Pinocchio, Cinderella, the Three Pigs, you name it) raid his sanctuary, saying they’ve been evicted by the vertically challenged Lord Farquaad. Shrek strikes a deal: He’ll get their homes back, if they give him his home back! But when Shrek and Farquaad meet, the Lord strikes a deal of his own: He’ll give the fairy-tale characters their homes back, if Shrek rescues Princess Fiona. Shrek obliges, yet finds something appealing - something strange and different - about this pretty princess. -

Study Guide Prepared by Patrick Brady and Jeri Hammond

SHREK THE MUSICAL a Wheelock Family Theatre Study Guide prepared by Patrick Brady and Jeri Hammond thanks and applause to The Yawkey Foundation sponsor of the student matinee series 200 The Riverway │ Boston, MA 02215-4176 box office: 617.879.2300 │ www.wheelockfamilytheatre.org Synopsis of Shrek the Musical ACT I The story begins when the ogre Shrek is kicked out of his parents’ home on his seventh birthday (“Big Bright Beautiful World”). His parents tell him that life will be difficult as an ogre, since “people hate the things they cannot understand.” Young Shrek has trouble fitting in, so he finds an isolated swamp to live in—alone, but content in his ways. He remains at his swamp for many happy years. One day, several fairy tale creatures arrive at Shrek’s swamp, disturbing his solitude. Per order of the cruel leader of Duloc, Lord Farquaad, all fairy tale creatures have been labeled “freaks” and banished from the kingdom. The creatures include the Three Little Pigs, Peter Pan, the Fairy Godmother, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, the Mad Hatter, the Big Bad Wolf, and, their leader, Pinocchio. They sing “Story of My Life,” bemoaning their terrible circumstances and their lack of a “happy ending.” Shrek is displeased with the newcomers and tries to send them away, but they beg him to save them from Lord Farquaad’s evildoing. When Shrek finally agrees to seek out Farquaad about this injustice, the creatures happily send him off (“The Goodbye Song”). On his way through the forest, Shrek meets a donkey who is escaping from Lord Farquaad’s soldiers; Shrek easily scares the men away. -

Shrek, the Musical Audition Packet Production Director: Kristina Turpin Technical Director: Cynthia Hersch

Shrek, the Musical Audition Packet Production Director: Kristina Turpin Technical Director: Cynthia Hersch AUDITIONS Wednesday, January 4th (Nutrition, Lunch, After School) Thursday, January 5th(Nutrition, Lunch, After School) Friday, January 6th(Nutrition and Lunch only) By appointment only. Sign-ups sheets and auditions will be at room 105. AUDITIONS will include ACTING, SINGING, and DANCING. Please plan to arrive 5 minutes before your scheduled appointment time and please be prepared to stay 5-10 minutes past your scheduled appointment time. ACTING: Please prepare (preferably memorized) one of the following monologues offered in this audition packet on the next page. SINGING: Please prepare a 1-2 minute solo performance (preferably memorized and blocked) of any song from Shrek, the Musical. You must provide your own instrumental accompaniment on a flash-drive, emailed file, or CD track. DANCING: Please learn the introduction routine to “WHAT’S UP DULOC”. The music will be provided at your DANCE audition only. Please use the following YouTube video link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BfNK5lHL2nA (only from 1:06-1:33) LYRICS: Welcome to duloc, Such a perfect town. Here we have some rules, Let us lay them down. Don't make waves, stay in line, And we'll get along fine. Duloc is a perfect place. Please keep off the grass Shine your shoes, wipe your'face. Duloc is, duloc is, duloc is a perfect place. THE CAST LIST (the results) WILL BE POSTED Friday, January 6th, 2017 after school (3:00pm) on the doors of room 105. PLEASE KEEP IN MIND… NOT EVERYONE WHO AUDITIONS WILL BE CASTED.