From Exchanging Weapons for Development to Security Sector Reform in Albania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mbi Shërbimet Sociale Në Territorin E Qarkut Elbasan

GUIDË mbi shërbimet sociale në territorin e Qarkut Elbasan Ky publikim është realizuar nga Këshilli i Qarkut Elbasan Guidë mbi shërbimet sociale Përmbajtja 1.Parathënia 2.Përshkrimi i bashkive sipas ndarjes së re territoriale 3.Hartëzimi i shërbimeve sociale (i shpjeguar) 4.Adresari 5.Sfidat dhe rekomandimet Kontribuan në realizimin e Guidës mbi shërbimet sociale në territorin e Qarkut Elbasan: Blendi Gremi, Shef i Sektorit të Kulturës dhe Përkujdesit Social, në Këshillin e Qarkut Elbasan Ardiana Kasa, Eksperte “Tjetër Vizion” Prill 2016 Guidë mbi shërbimet sociale Parathënie Kam kënaqësinë të shpreh të gjitha falenderimet e mia për drejtuesit dhe specialistët e Këshillit të Qarkut Elbasan si dhe ekspertët e fushës, të cilët u bënë pjesë e hartimit dhe finalizimit të Guidës mbi shërbimet sociale në Territorin e Qarkut Elbasan, një guidë e qartë e situatës aktuale sociale në Qarkun e Elbasanit. Publikimi ka si objektiv tё prezantojё nё mёnyrё tё plotё mundёsitё e ofruara nga shërbimet sociale publike dhe jo publike nё mbёshtetje tё njerëzve nё nevojë, si dhe shёrbimet ekzistuese nё territor pёr to. Nё kёtё këndvështrim, publikimi mund tё shihet si njё lloj “udhërrëfyesi” ku mund të sigurohen, nё mёnyrё sintetike e tё qartё, informacione nё lidhje me tё gjitha shёrbimet nё favor tё shtresave më në nevojë tё ofruara nga ente publike e private nё Qarkun e Elbasanit. Ky publikim përcakton, burimet ekzistuese, nevojat e ndërhyrjes, mungesat, sfidat e përballura si dhe rekomandimet për të ardhmen. Kjo guidë do t’i vijë në ndihmë hartimit të planveprimit të përfshirjes sociale të Bashkisë Elbasan si dhe bashkive të tjera, pjesë e Qarkut Elbasan dhe do t’i hapë rrugë përqasjes së donatorëve vendas dhe të huaj në zbatimin e projekteve të nevojshme në fushën sociale. -

Albania: Average Precipitation for December

MA016_A1 Kelmend Margegaj Topojë Shkrel TRO PO JË S Shalë Bujan Bajram Curri Llugaj MA LËSI Lekbibaj Kastrat E MA DH E KU KË S Bytyç Fierzë Golaj Pult Koplik Qendër Fierzë Shosh S HK O D Ë R HAS Krumë Inland Gruemirë Water SHK OD RË S Iballë Body Postribë Blerim Temal Fajza PUK ËS Gjinaj Shllak Rrethina Terthorë Qelëz Malzi Fushë Arrëz Shkodër KUK ËSI T Gur i Zi Kukës Rrapë Kolsh Shkodër Qerret Qafë Mali ´ Ana e Vau i Dejës Shtiqen Zapod Pukë Malit Berdicë Surroj Shtiqen 20°E 21°E Created 16 Dec 2019 / UTC+01:00 A1 Map shows the average precipitation for December in Albania. Map Document MA016_Alb_Ave_Precip_Dec Settlements Borders Projection & WGS 1984 UTM Zone 34N B1 CAPITAL INTERNATIONAL Datum City COUNTIES Tiranë C1 MUNICIPALITIES Albania: Average Produced by MapAction ADMIN 3 mapaction.org Precipitation for D1 0 2 4 6 8 10 [email protected] Precipitation (mm) December kilometres Supported by Supported by the German Federal E1 Foreign Office. - Sheet A1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Data sources 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 - - - 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 The depiction and use of boundaries, names and - - - - - - - - - - - - - F1 .1 .1 .1 GADM, SRTM, OpenStreetMap, WorldClim 0 0 0 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 associated data shown here do not imply 6 7 8 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 endorsement or acceptance by MapAction. -

Qendra Shëndetësore Adresa E Vendndodhjes Numër Kontakt Adresë E-Mail

Qendra Shëndetësore Adresa e vendndodhjes Numër kontakt Adresë e-mail Berat QSH Cukalat Cukalat 696440228 [email protected] Berat QSH Kutalli Kutalli 36660431 [email protected] Berat QSh Lumas Lumas 695305036 [email protected] Berat QSh Otllak Lapardha 1 696614266 [email protected] Berat QSH Poshnje Poshnje 682009616 [email protected] Berat QSH Nr.1 “Jani Vruho” 32236136 [email protected] Berat Qsh NR.2 “22 Tetori” 32231366 [email protected] Berat QSh Nr.3 “Muzakaj” 32230799 [email protected] Berat QSh Roshnik Roshnik 692474222 Berat QSh Sinje Sinje 674059965 Berat Qsh Terpan Terpan 694793160 Berat QSh Ura vajgurore L"18 tetori" 36122793 Berat QSH Velabisht Velabisht 694647940 Berat QSh Vertop Vertop 694034408 Berat QSH Kozare Mateniteti i vjetër ”Havaleas” 698905288 Berat QSH Perondi Perondi 692750571 Berat QSH Kuçove Lgj ’Vasil Skendo” 31122801 Berat QSH Bogove-Vendresh Bogove 692405144 Berat QSH Çepan Çepan 692169333 Berat QSH Poliçan Rr ”Miqesia" 36824433 QSH Qender-Leshnje- Berat "Hasan Seitaj" 682039993 Potom-Gjerbes-Zhepe Berat QSH Çorovode ”Hasan Seitaj” 698356399 Dibër Peshkopi Qytet 682061580 Dibër Arras Fshat 673000110 Dibër Fushe-Alie Fshat 674711166 Dibër Kala e Dodes Fshat 684060111 Dibër Kastriot Fshat 693941400 Dibër Lure Fshat 683425115 Dibër Luzni Fshat 672587497 Dibër Maqellare Fshat 684050700 Dibër Melan Fshat 682003899 Dibër Muhurr Fshat 684007999 Dibër Selishte Fshat 684007999 Dibër Sllove Fshat 682529544 Dibër Tomin Fshat 682012793 Dibër Zall-Dardhe Fshat 684007999 Dibër Zall-Reç Fshat 684007999 -

LIDHJA 1 Qarku Bashkia Njësia Administrative ZAZ Nr Zyra KZAZ-Ve

LIDHJA 1 Qarku Bashkia Njësia Administrative ZAZ Nr Zyra KZAZ-ve Koplik Gruemirë KOPLIK Kastrat MALËSI E MADHE 01 Drejtoria e Bujqesise Kelmend (Kati i dyte) Qendër Shkrel Ana Malit Bërdicë Dajç Gur i zi Postribë SHKODER 02 Pult Konvikti i shkolles pyjore Shosh Rrethinat Shalë Velipojë Shkodër (zona QV 0235 deri 0245, SHKODER Shkodër zona QV 0269, zona QV 0279, zona QV 0280, zona QV 0282, zona QV 03 Shkolla 9-vjecare SHKODËR 0284, zona QV 0286 deri 0297, dhe "Ismail Dervishi" zona QV 0299 deri 0304) Shkodër (zona QV 0246 deri 0263, zona QV 0265 deri 0268, zona QV SHKODER 0270, zona QV 0276, zona QV 0316, 04 Shkolla 9-vjecare zona QV 0318, zona QV 0319 dhe "Xheladin Fishta" zona QV 0321) Shkodër (zona QV 0271 deri 0275, zona QV 0277, zona QV 278, zona QV 281, zona QV 0283, zona QV SHKODER 0285, zona QV 0298, zona QV 0305 05 Shkolla Pyjore deri 0315, zona QV 0317, zona QV (Konvikti) 0320, zona QV 0322 dhe zona QV 0323) Vau - Dejës Temal BUSHAT Shkolla e Mesme Bushat VAU - DEJËS 06 Profesionale Hajmel “Ndre Mjeda” Vig-Mnelë ( Palestra) Shllak Pukë Pukë Rrapë Shkolla e Mesme e PUKË Gjegjan 07 Bashkuar Shkodër Qerret (Palestra) Qelëz Fushë-Arrëz Blerim Fushë Arrëz FUSHË ARRËZ Qafë Mali 08 Qendra e Kultures se Fierzë Femijeve Iballë Miratuar me Vendim të KQZ-së Nr.85, datë 07.04.2015 LIDHJA 1 Qarku Bashkia Njësia Administrative ZAZ Nr Zyra KZAZ-ve Bajram Curri Bujan KOPLIK Bytyc MALËSI E MADHE 01 Drejtoria e Bujqesise Fierzë Bajram Curri TROPOJË 09 (Kati i dyte) Lekbibaj Shkolla e Mesme Llugaj Margegaj Tropojë Krumë Krumë Gjinaj HAS 10 Zyra -

Dwelling and Living Conditions

Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC ALBANIA DWELLING AND LIVING CONDITIONS M a y, 2 0 1 4 ALBANIA DWELLING AND LIVING CONDITIONS Preface and Acknowledgment May, 2014 The 2011 Population and Housing Census of Albania is the 11th census performed in the history of Director of the Publication: Albania. The preparation and implementation of this commitment required a significant amount Gjergji FILIPI, PhD of financial and human resources. For this INSTAT has benefitted by the support of the Albanian government, the European Union and international donors. The methodology was based on the EUROSTAT and UN recommendations for the 2010 Population and Housing Censuses, taking into INSTAT consideration the specific needs of data users of Albania. Ledia Thomo Anisa Omuri In close cooperation with international donors, INSTAT has initiated a deeper analysis process in Ruzhdie Bici the census data, comparing them with other administrative indicators or indicators from different Eriona Dhamo surveys. The deepened analysis of Population and Housing Census 2011 will serve in the future to better understand and interpret correctly the Albanian society features. The information collected by TECHNICAL ASSISTENCE census is multidimensional and the analyses express several novelties like: Albanian labour market Juna Miluka and its structure, emigration dynamics, administrative division typology, population projections Kozeta Sevrani and the characteristics of housing and dwelling conditions. The series of these publications presents a new reflection on the situation of the Albanian society, helping to understand the way to invest in the infrastructure, how to help local authorities through Copyright © INSTAT 2014 urbanization phenomena, taking in account the pace of population growth in the future, or how to address employment market policies etc. -

Pa Sjell Harta.Pdf

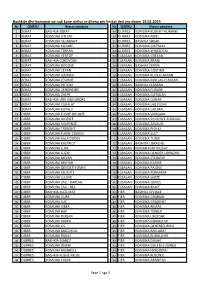

Bashkite dhe komunat qe nuk kane sjellur te dhena për hartat deri me daten 13.02.2015 Nr QARKU Njesia vendore Nr QARKU Njesia vendore 1 BERAT BASHKIA BERAT 49 DURRES KOMUNA KODER-THUMANE 2 BERAT KOMUNA OTLLAK 50 DURRES KOMUNA NIKEL 3 BERAT KOMUNA VELABISHT 51 DURRES BASHKIA SHIJAK 4 BERAT KOMUNA KOZARE 52 DURRES KOMUNA GJEPALAJ 5 BERAT KOMUNA TERPAN 53 DURRES KOMUNA XHAFZOTAJ 6 BERAT KOMUNA VERTOP 54 ELBASAN KOMUNA GREKAN 7 BERAT BASHKIA COROVODE 55 ELBASAN KOMUNA RRASE 8 BERAT KOMUNA BOGOVE 56 ELBASAN BASHKIA CERRIK 9 BERAT KOMUNA CEPAN 57 ELBASAN KOMUNA GOSTIME 10 BERAT KOMUNA GJERBES 58 ELBASAN KOMUNA KLOS-ELBASAN 11 BERAT KOMUNA LESHNJE 59 ELBASAN KOMUNA MOLLAS-ELBASAN 12 BERAT KOMUNA POTOM 60 ELBASAN BASHKIA ELBASAN 13 BERAT KOMUNA VENDRESHE 61 ELBASAN KOMUNA FUNARE 14 BERAT KOMUNA ZHEPE 62 ELBASAN KOMUNA GJERGJAN 15 BERAT BASHKIA URA VAJGURORE 63 ELBASAN KOMUNA GJINAR 16 BERAT KOMUNA CUKALAT 64 ELBASAN KOMUNA LAB.FUSHE 17 BERAT KOMUNA KUTALLI 65 ELBASAN KOMUNA LAB.MAL 18 DIBER KOMUNA FUSHE-BULQIZE 66 ELBASAN KOMUNA SHIRGJAN 19 DIBER KOMUNA GJORICE 67 ELBASAN KOMUNA SHUSHICE-ELBASAN 20 DIBER KOMUNA SHUPENZE 68 ELBASAN KOMUNA ZAVALIN 21 DIBER KOMUNA TREBISHT 69 ELBASAN KOMUNA PISHAJ 22 DIBER KOMUNA FUSHE-CIDHEN 70 ELBASAN KOMUNA SULT 23 DIBER KOMUNA KALA DODES 71 ELBASAN KOMUNA TUNJE 24 DIBER KOMUNA KASTRIOT 72 ELBASAN BASHKIA LIBRAZHD 25 DIBER KOMUNA LURE 73 ELBASAN KOMUNA HOTOLISHT 26 DIBER KOMUNA LUZNI 74 ELBASAN KOMUNA QENDER-LIBRAZHD 27 DIBER KOMUNA MELAN 75 ELBASAN KOMUNA STEBLEVE 28 DIBER KOMUNA MUHUR 76 ELBASAN KOMUNA KARINE -

Subjekte Të Autorizuar Për Ofrimin E Shërbimit Të Programit

TË DHËNA TË SUBJEKTIT KONTAKT EMRI I SUBJEKTIT NR. (OSHMA)IPTV/OTT/In EMRI I PERSONIT AFATI ternet/ Kabllorë NIPT-I ORTAKËT (AKSIONERËT) ZONA E LICENCIMIT/AUTORIZIMIT ADRESA TELEFON E-MAIL FIZIK (JURIDIK) LICENCIMIT/AUTORIZIMIT Rruga e "Durresit 1 Elida Llupa L81419038G Elida Llupa (100%) 16.05.2018 - 16.05.2023 Republika e Shqipërisë "pall.220/shk21/1/1, Tiranë. 0674037713 [email protected] "Elrodi Tv" Shoqëria “Premium Rruga “Ibrahim Rugova”, Pallatet Enver Mehmeti (70%) Media”sh.p.k. 07.12.2018 - 07.12.2023 Shallvare përballë Kompleksit 2 "Premium Travel" L72414030K Gentian Ferhati (30%) Republika e Shqipërisë 0693120307 [email protected] SH.P.K. Tajvan, Kati 2, Tiranë Rruga: “Muhamet Gjollesha”, Altin Cela (70%) Shoqëria “Super 19.05.2016 - 19.05.2021 pallati 60/1, shk. 1, ap. 2, Tiranë 3 L41407004E Diana Hoxha Cerova (15%) Online 0694041343 [email protected] “STV” Sonic” shpk Riza Hoxha Cerova (15%) Rruga: “Muhamet Gjollesha”, Altin Cela (70%) Shoqëria “Super pallati 60/1, shk. 1, ap. 2, Tiranë 4 L41407004E Diana Hoxha Cerova (15%) 19.05.2016 - 19.05.2021 Online 0694041343 [email protected] “STV Folk” Sonic” shpk Riza Hoxha Cerova (15%) Rruga: “Ismail Qemali”, pallati XI, Shoqëria “Tema TV” Soqëria “OTTIG” sh.p.k. 19.05.2016-19.05.2021 5 "Tema Tv" L42404004O Online kati 2 (sipër Eurolloto/telesport) 0692939256 [email protected]; shpk. (100%) Lagjja Popullore, Rruga Gani Keta, Shoqëria “TV Gold” Artan Xhaferi “ TV Gold” 21.08.2020- 21.08.2025 zone kadastrale 3369, nr pasurie 6 sh.p.k. M01324502F administrator(60%) Online 0682020291 jxhafa@gmail 102/1, nr godine 5, kati i pare, Ardjana Merko (40%) Shijak, Durres. -

K U K Ës S H K Od Ër

LIDHJA NR. 1 NJËSITË ADMINISTRATIVE KU DO TE KRIJOHEN SELITË E KZAZ-VE PËR ZGJEDHJET PËR KUVENDIN E SHQIPËRISË TË DATËS 25 PRILL 2021 Lidhja 1 Njesia admnistrative ku krijohet Selia e Nr. Qarku Nr. Bashkia Nr. Njësitë admnistrative ZAZ Nr KZAZ-së 1 Gruemirë 2 Kastrat 3 Kelmend 1 MALËSI E MADHE 01 Koplik 4 Koplik 5 Qendër-Malesi e Madhe 6 Shkrel 7 Ana Malit 8 Berdicë 9 Dajç 10 Gur i zi 11 Postribë 02 Shkodër 12 Pult 13 Rrethinat 14 Shalë,Shosh 15 Velipojë Shkodër (zona QV 0235 deri 0245, zona QV 0269, zona QV 0279, zona QV 0280, zona QV 0282, zona QV 0284, zona QV 03 Shkodër 2 SHKODËR 0286 deri 0297 dhe zona QV 0299 deri 0304) 1 Shkodër (zona QV 0246 deri 0263, zona QV 0265 deri 0268, zona QV 0270, zona 04 Shkodër Shkodër 16 QV 0276, zona QV 0316, zona QV 0318, zona QV 0319 dhe zona QV 0321) Shkodër (zona QV 0271 deri 0275, zona QV 0277, zona QV 278, zona QV 281, zona QV 0283, zona QV 0285, zona QV 05 Shkodër 0298, zona QV 0305 deri 0315, zona QV 0317, zona QV 0320, zona QV 0322 dhe zona QV 0323) 17 Bushat 18 Hajmel,Vig Mnele 3 VAU-DEJËS 06 Bushat 19 Shllak 20 Vau Dejes,Temal 21 Gjegjan 4 PUKË 22 Pukë,Rrapë 07 Pukë 23 Qerret,Qelëz 24 Fierzë 5 FUSHË-ARRËZ 25 Fushë Arrëz,Qafë Mali,Blerim 08 Fushë Arrëz 26 Iballë 27 B. Curri 28 Bujan 29 Bytyc 30 Fierzë 6 TROPOJË 09 Bajram Curri 31 Lekbibaj 32 Llugaj 33 Margegaj 34 Tropojë 2 Kukës 35 Fajzë 7 HAS 36 Golaj 10 Krumë 37 Krumë,Gjinaj 38 Bicaj,Ujmisht 8 KUKËS Miratuar me vendim nr.... -

Mapping of Hydropower Plant in Albania, Using Geographic Information System

Mapping of hydropower plant in Albania, using Geographic Information System © HELP-CSO project Compiled and prepared by: Author: Lorela Lazaj 1, Rineldi Xhelilaj 2 EcoAlbania 1GIS expert; [email protected] Miliekontakt Albania 2Architect; [email protected] LexFerenda April 2017 1 of 37 Mapping of hydropower plant in Albania, using Geographic Information System Abstract: The hydropower industry business has been growing very fast in Albania since 2007. Few studies have been published recently about the environmental and social impacts of this industry. Mapping of the existing hydropower plants and those which are planned to be developed is a must, in order to understand and estimate the consequences and to develop the proper conservation plans. GIS is shown to be a very useful tool, in environmental management and protection in different fields, including hydrology. This paper includes: a desk research on the identification of hydropower plants’ geographic location, and additional data associated with each one such as: the company’s name, power, capacity, basin, etc.; also the mapping and classification of the hydropower in different categories. The purpose of this project is to: create an open geodatabase, available to everyone who needs the information regarding the existing and planned hydropower plants in Albania; create an interactive map integrated into the webpage; mapping the HPPs conflicts. Keywords: GIS; hydropower; Albania; hydrology; environment; dam; protected areas Partnership was considered as a great 1. Introduction opportunity for the sector of hydropower. Albania is located in the western part of the Therefore, the interest for the hydropower sector Balkan Peninsula. Its hydrographic territory has grew rapidly, by providing enormous benefits a surface of 44,000 km square, with an average for the private sector and at the same time height of the hydrographic territory of about 700 meeting people’s needs for electricity. -

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION Republic of Albania – Local Government Elections, 8 May 2011

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION Republic of Albania – Local Government Elections, 8 May 2011 STATEMENT OF PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS Tirana, 10 May 2011– This Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions is the result of a common endeavour involving the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) and the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe (Congress). The 2011 local elections were assessed for their compliance with OSCE and Council of Europe commitments for democratic elections, as well as with the legislation of Albania. This statement is delivered prior to the completion of the election process. The OSCE/ODIHR will issue a comprehensive final report, including recommendations for potential improvements, some eight weeks after the completion of the election process. The Bureau of the Congress will discuss a report and will adopt a draft recommendation and resolution at its next meeting in mid-June. The report and texts will then be considered for adoption by the Congress at its next plenary session, in mid-October 2011. The institutions represented wish to thank the authorities, political parties and civil society for their co- operation and stand ready to continue their support for the conduct of democratic elections. PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS The 8 May 2011 local government elections in the Republic of Albania were competitive and transparent, but took place in an environment of high polarization and mistrust between parties in government and opposition. As in previous elections the two largest political parties did not discharge their electoral duties in a responsible manner, negatively affecting the administration of the entire process. -

Popullsia (Qytet, Bashki, Qark) Ministria E Puneve Te

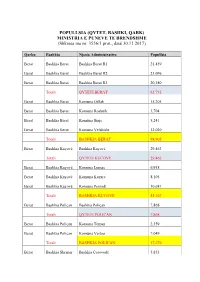

POPULLSIA (QYTET, BASHKI, QARK) MINISTRIA E PUNEVE TE BRENDSHME (Shkresa me nr. 3556/1 prot., datë 30.11.2017) Qarku Bashkia Njesia Administrative Popullsia Berat Bashkia Berat Bashkia Berat R1 21,459 Berat Bashkia Berat Bashkia Berat R2 21,096 Berat Bashkia Berat Bashkia Berat R3 20,180 Totali QYTETI BERAT 62,735 Berat Bashkia Berat Komuna Otllak 15,205 Berat Bashkia Berat Komuna Roshnik 3,704 Berat Bashkia Berat Komuna Sinje 5,241 Berat Bashkia Berat Komuna Velabisht 12,020 Totali BASHKIA BERAT 98,905 Berat Bashkia Kuçovë Bashkia Kuçovë 29,463 Totali QYTETI KUCOVE 29,463 Berat Bashkia Kuçovë Komuna Lumas 6,918 Berat Bashkia Kuçovë Komuna Kozare 8,105 Berat Bashkia Kuçovë Komuna Perondi 10,681 Totali BASHKIA KUCOVE 55,167 Berat Bashkia Poliçan Bashkia Poliçan 7,868 Totali QYTETI POLICAN 7,868 Berat Bashkia Poliçan Komuna Terpan 2,359 Berat Bashkia Poliçan Komuna Vertop 7,049 Totali BASHKIA POLICAN 17,276 Berat Bashkia Skrapar Bashkia Çorovodë 5,853 Totali QYTETI COROVODE 5,853 Berat Bashkia Skrapar Komuna Bogovë,Komuna Vendresh 2,884 Berat Bashkia Skrapar Komuna Cepan 968 Berat Bashkia Skrapar Komuna Gjerbes,Komuna Zhepë 2,050 Berat Bashkia Skrapar Komuna Potom 1,099 Komuna Qendër _ SKRAPAR,Komuna Berat Bashkia Skrapar Leshnjë 4,639 Totali BASHKIA SKRAPAR 17,493 Bashkia Ura Berat Vajgurore Bashkia Ura Vajgurore 11,809 Totali QYTETI URA VAJGURORE 11,809 Bashkia Ura Berat Vajgurore Komuna Kutalli 13,513 Bashkia Ura Berat Vajgurore Komuna Poshnje 10,295 Bashkia Ura Berat Vajgurore Komuna Cukalat 4,259 Totali BASHKIA URA VAJGURORE 39,876 -

Urban Rural Albanian Population

A NEW URBANRURAL CLASSIFICATION OF ALBANIAN POPULATION THE EU GEOGRAPHICAL TYPOLOGY BASED ON GRID DATA May, 2014 A NEW URBAN-RURAL CLASSIFICATION OF ALBANIAN POPULATION MAY, 2014 Director of the Publication: Gjergji FILIPI, PhD INSTAT Ervin Shameti Nexhmije Lecini EU TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE Roberto Bianchini Copyright © INSTAT 2014 No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Disclaimer: This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this European Union. Printed with the support of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. ISBN: 978 - 9928 - 188 - 10 -6 INSTITUTI I STATISTIKAVE Blv. “Zhan D’Ark” Nr. 3, Tiranë Tel : + 355 4 2222411 / 2233356 Fax : + 355 4 2228300 E-mail : [email protected] Printing house: Preface and acknowledgements Statistical data for urban and rural areas are of some considerable importance for the central government and for local authorities while planning and managing services for local communities. For instance, the allocation of health and social care funding, housing, roads, water and sewerage and the provision and maintenance of schools have all distinctive aspects in urban and rural areas. Employment for urban and rural population has different features as well. In Albania, as in most other countries, it is difficult to distinguish exactly the urban population from the rural one. Even though not always reflecting what is certainly urban or rural, in Albania, the administrative definition based on the law is used also for statistical purposes. However, the present availability of small-area data derived from the 2011 population and housing census covering the entire territory of the country, has made possible an attempt to introduce also in Albania new definitions and classifications of urban and rural areas for statistical purposes.