Fair Comment, Judges and Politics in Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hansard (English)

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 13 October 2005 45 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 13 October 2005 The Council met at Three o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. 46 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 13 October 2005 THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE YEUNG SUM THE HONOURABLE LAU CHIN-SHEK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. -

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

The 2012 Election Reforms

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: The 2012 Election Reforms (name redacted) Specialist in Asian Affairs February 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R40992 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: The 2012 Election Reforms Summary Support for the democratization of Hong Kong has been an element of U.S. foreign policy for over 17 years. The Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-383) states, “Support for democratization is a fundamental principle of United States foreign policy. As such, it naturally applies to United States policy toward Hong Kong. This will remain equally true after June 30, 1997” (the date of Hong Kong’s reversion to China). The Omnibus Appropriations Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-8) provides at least $17 million for “the promotion of democracy in the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan …” The democratization of Hong Kong is also enshrined in the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s quasi- constitution that was passed by China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) prior to China’s resumption of sovereignty over the ex-British colony on July 1, 1997. The Basic Law stipulates that the “ultimate aim” is the selection of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and the members of its Legislative Council (Legco) by “universal suffrage.” However, it does not designate a specific date by which this goal is to be achieved. On November 18, 2009, Hong Kong Chief Executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen released the long- awaited “consultation document” on possible reforms for the city’s elections to be held in 2012. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2016-17 Reply Serial No. HAB145 CONTROLLING OFFICER's REPLY (Question Serial No

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2016-17 Reply Serial No. HAB145 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY (Question Serial No. 3023) Head: (74) Information Services Department Subhead (No. & title): (-) Not Specified Programme: (2) Local Public Relations and Public Information Controlling Officer: Director of Information Services (Patrick T K NIP) Director of Bureau: Secretary for Home Affairs Question: Will the Government advise this Committee:- (1) the operational expenses, staff establishment and annual provision for salaries under this Programme in 2016-17; and (2) the respective expenditure on promoting “Appreciate Hong Kong” and the Basic Law in 2016-17? Asked by: Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip (Member Question No. 61) Reply: (1) Under Programme 2 “Local Public Relations and Public Information”, the financial provision for 2016-17 is $212.7 million including $172.7 million for personal emoluments, and the staff establishment is 249. (2) No expenditure is expected to incur in 2016-17 on promoting the “Appreciate Hong Kong” campaign which will run till end April 2016, and the Basic Law. - End - Session 10 HAB - Page 422 Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2016-17 Reply Serial No. HAB146 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY (Question Serial No.1479) Head: (74) Information Services Department Subhead (No. & title): (-) Not Specified Programme: (1) Public Relations Outside Hong Kong Controlling Officer: Director of Information Services (Patrick T K NIP) Director of Bureau: Secretary for Home Affairs Question: The Information Services Department (ISD) aims at projecting a good image of Hong Kong globally and says that it will make use of Facebook, YouTube and Instagram to extend the reach of publicity efforts around the world. -

Minutes of the 27Th Meeting Held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 Pm on Friday, 25 June 2021

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1238/20-21 Ref : CB2/H/5/20 House Committee of the Legislative Council Minutes of the 27th meeting held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 pm on Friday, 25 June 2021 Members present : Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, SBS, JP (Chairman) Hon MA Fung-kwok, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, GBS, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, GBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, GBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan, BBS, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, GBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, SBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP Hon Steven HO Chun-yin, BBS Hon Frankie YICK Chi-ming, SBS, JP Hon YIU Si-wing, BBS Hon CHAN Han-pan, BBS, JP Hon LEUNG Che-cheung, SBS, MH, JP Hon Alice MAK Mei-kuen, BBS, JP Hon KWOK Wai-keung, JP Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, SBS, JP Hon Elizabeth QUAT, BBS, JP Hon Martin LIAO Cheung-kong, GBS, JP Hon POON Siu-ping, BBS, MH Dr Hon CHIANG Lai-wan, SBS, JP Ir Dr Hon LO Wai-kwok, SBS, MH, JP Hon CHUNG Kwok-pan Hon Jimmy NG Wing-ka, BBS, JP Dr Hon Junius HO Kwan-yiu, JP Hon Holden CHOW Ho-ding Hon SHIU Ka-fai, JP Hon Wilson OR Chong-shing, MH Hon YUNG Hoi-yan, JP -2 - Dr Hon Pierre CHAN Hon CHAN Chun-ying, JP Hon CHEUNG Kwok-kwan, JP Hon LUK Chung-hung, JP Hon LAU Kwok-fan, MH Hon Kenneth LAU Ip-keung, BBS, MH, JP Dr Hon CHENG Chung-tai Hon Vincent CHENG Wing-shun, MH, JP Hon Tony TSE Wai-chuen, BBS, JP Members absent : Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, JP Clerk in attendance : Miss Flora TAI -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Legco Members Meet with Members of Kwai Tsing and Wong Tai Sin District Councils (With Photos)

LegCo Members meet with members of Kwai Tsing and Wong Tai Sin District Councils (with photos) The following is issued on behalf of the Legislative Council Secretariat: Members of the Legislative Council (LegCo) held separate meetings today (March 22) with members of the Kwai Tsing District Council (DC) and the Wong Tai Sin DC respectively at the LegCo Complex to discuss and exchange views on matters of mutual interest. During the meeting with the Kwai Tsing DC, LegCo Members discussed and exchanged views with DC members on the requests for constructing lift and footbridge facilities in Kwai Tsing District; the proposal for the Housing Department to install dog latrines in all housing estates in Hong Kong; the concerns about the use of Besser blocks for surfacing pavements; tackling the problem of shortage of parking spaces; and the enhancement of the follow-up work by the Department of Health with regard to the Colorectal Cancer Screening Programme. The meeting was convened by Dr Junius Ho and attended by Mr Abraham Shek, Ms Starry Lee, Mr Chan Han-pan, Ms Alice Mak, Dr Lo Wai- kwok, Mr Andrew Wan, Mr Chu Hoi-dick, Mr Holden Chow, Mr Shiu Ka-chun, Dr Pierre Chan, Mr Lau Kwok-fan, Dr Cheng Chung-tai and Mr Tony Tse. As for the meeting with the Wong Tai Sin DC, LegCo Members discussed and exchanged views with DC members on the request for the Government to engage independent third parties to review the workmanship of the canopy structures of buildings in Chuk Yuen (North) Estate; the retrofitting of barrier-free access facilities in Chuk Yuen (North) Estate; the retrofitting of lifts at the footbridge connecting Choi Fai Estate and Choi Wan (II) Estate; the redevelopment of Choi Hung Road Market to provide other community facilities; the provision of a dental clinic with general public sessions in Wong Tai Sin District; and the redevelopment of the Ngau Chi Wan Village Squatter Area. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 February 2015 6007 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11 February 2015 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. 6008 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 11 February 2015 THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONNY TONG KA-WAH, S.C. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

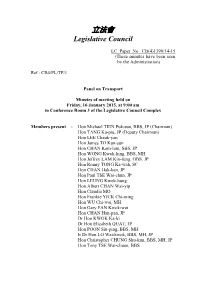

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(4)1390/14-15 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB4/PL/TP/1 Panel on Transport Minutes of meeting held on Friday, 16 January 2015, at 9:00 am in Conference Room 3 of the Legislative Council Complex Members present : Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP (Chairman) Hon TANG Ka-piu, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHAN Kam-lam, SBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-hing, BBS, MH Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Hon CHAN Hak-kan, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon Claudia MO Hon Frankie YICK Chi-ming Hon WU Chi-wai, MH Hon Gary FAN Kwok-wai Hon CHAN Han-pan, JP Dr Hon KWOK Ka-ki Dr Hon Elizabeth QUAT, JP Hon POON Siu-ping, BBS, MH Ir Dr Hon LO Wai-kwok, BBS, MH, JP Hon Christopher CHUNG Shu-kun, BBS, MH, JP Hon Tony TSE Wai-chuen, BBS - 2 - Members attending : Hon CHAN Yuen-han, SBS, JP Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung Member absent : Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Public Officers : Agenda item III attending Mrs Ingrid YEUNG, JP Commissioner for Transport Mr CHEUNG Jin-pang Assistant Commissioner for Transport/Administration & Licensing Ms Cordelia LAM Principal Assistant Secretary for Transport and Housing (Transport)2 Agenda item IV Mr YAU Shing-mu, JP Under Secretary for Transport and Housing Ms Rebecca PUN Ting-ting, JP Deputy Secretary for Transport and Housing (Transport)1 Miss Winnie WONG Ming-wai Principal Assistant Secretary for Transport and Housing (Transport)3 Mr Peter LAU Ka-keung, -

PDF Full Report

Heightening Sense of Crises over Press Freedom in Hong Kong: Advancing “Shrinkage” 20 Years after Returning to China April 2018 YAMADA Ken-ichi NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute Media Research & Studies _____________________________ *This article is based on the same authors’ article Hong Kong no “Hodo no Jiyu” ni Takamaru Kikikan ~Chugoku Henkan kara 20nen de Susumu “Ishuku”~, originally published in the December 2017 issue of “Hoso Kenkyu to Chosa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcast Research]”. Full text in Japanese may be accessed at http://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/oversea/pdf/20171201_7.pdf 1 Introduction Twenty years have passed since Hong Kong was returned to China from British rule. At the time of the 1997 reversion, there were concerns that Hong Kong, which has a laissez-faire market economy, would lose its economic vigor once the territory is put under the Chinese Communist Party’s one-party rule. But the Hong Kong economy has achieved generally steady growth while forming closer ties with the mainland. However, new concerns are rising that the “One Country, Two Systems” principle that guarantees Hong Kong a different social system from that of China is wavering and press freedom, which does not exist in the mainland and has been one of the attractions of Hong Kong, is shrinking. On the rankings of press freedom compiled by the international journalists’ group Reporters Without Borders, Hong Kong fell to 73rd place in 2017 from 18th in 2002.1 This article looks at how press freedom has been affected by a series of cases in the Hong Kong media that occurred during these two decades, in line with findings from the author’s weeklong field trip in mid-September 2017.