The Gist and Drift of God of Small Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

The 2019 JCB Prize for Literature Shortlist Announced

PRESS RELEASE th For Immediate Release: Friday 4 October 2019 The 2019 JCB Prize for Literature shortlist announced ➢ Two debut authors in the running for India’s richest literary award ➢ Shortlist reflects great diversity of Indian writing today ➢ Five bold novels share a deep sense of justice and injustice 4th October 2019, New Delhi: Roshan Ali, Manoranjan Byapari, Perumal Murugan, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar and Madhuri Vijay were announced today as the five authors shortlisted for the 2019 JCB Prize for Literature. The shortlist was announced this morning by Pradip Krishen, Chair of the 2019 jury, and Rana Dasgupta, Literary Director of the Prize, in a press conference at Oxford Bookstore in New Delhi. The shortlist was selected by a panel of five judges: Pradip Krishen, filmmaker and environmentalist (Chair); Anjum Hasan, author and critic; K.R. Meera, author; Parvati Sharma, author; and Arvind Subramanian, economist and former Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India. The JCB Prize for Literature celebrates the very finest achievements in Indian writing. It is presented each year to a distinguished work of fiction by an Indian writer, as selected by the jury. The 2019 shortlist is: ● Ib's Endless Search for Satisfaction by Roshan Ali (Penguin Random House India, 2019) ● There's Gunpowder in the Air by Manoranjan Byapari, translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha (Westland Publications, 2018) ● Trial by Silence and Lonely Harvest by Perumal Murugan, translated from the Tamil by Aniruddhan Vasudevan (Penguin Random House India, 2018) ● My Father's Garden by Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar (Speaking Tiger Publishing Private Limited, 2018) ● The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay (HarperCollins India, 2019) Commenting on the shortlist, the chair of the 2019 jury, Pradip Krishen, said, "Bringing voices from across the country, these novels address the many specific difficulties of living a life in Indian society. -

Duke Kunshan Conference on Environmental Humanities in Asia: Environmental Justice and Sustainable Citizenship

Duke Kunshan conference on Environmental Humanities in Asia: Environmental Justice and Sustainable Citizenship May 22-24, 2017 Draft Agenda (V4) – April 24, 2017 Environmental Justice and Sustainable Citizenship Duke Global Asia Initiative and Duke Kunshan University May 22 – 24, 2017 Speaker Biographies PLENARY SESSION: What can Humanities and Interpretive Social Sciences do for Environmental Studies? Moderator: Prasenjit Duara, Director, Global Asia Initiative, Duke University Shuyuan Lu Professor and Director of Research Center for Eco-Cultural Institute of Science, Huanghe Science & Technology College "Ecology, Religion and Modernization: The Maitraiya Bodhimanda/Dojo and Nuo Religion in Mt. Fangjing from a Deep Ecological Perspective” Lu Shuyuan, Professor and director of Research Center for Eco-Cultural Institute of Science, Huanghe Science & Techonogy College; Vice President of The Chinese Literary and Arts Theories Association; a committee of the UNESCO "Humans and Biosphere" program, China. Prof. Lu has been conducting interdisciplinary research in the areas of literature, psychology, and ecology. His most representative works include the following books: A Study of Creative Pscyhology, Beyond Language, The Space of Ecological Criticism, Tao Yuanming's Specter, and The Ecological Era and Classical Chinese Naturalism. Fanren Zeng Former President, Shandong University "Chinese and Western Eco-Aesthetics: A Cross-Cultural Perspective" (Interpreter for Profs, Lu & Zeng will be Prof Chia-ju Chang) Duke Kunshan conference on Environmental Humanities in Asia: Environmental Justice and Sustainable Citizenship May 22-24, 2017 Draft Agenda (V4) – April 24, 2017 Dan Guttman Clinical Professor of Environmental Studies and Law, New York University – Shanghai The Global Vernacular of Governance: Translating Between China and US Environmental OS: A Core Task for Humanities Dan Guttman, is teacher, lawyer, and has been public servant. -

Sabrang Elections 2004: FACTSHEETS

Sabrang Elections 2004: FACTSHEETS Scamnama: The unending saga of NDA’s scams – Armsgate, Coffinsgate, Customscam, Stockscam, Telecom, Pumpscam… Scandalsheet 2: Armsgate (Tehelka) __________________________________________________________________ ‘Zero tolerance of corruption’. -- Prime Minister Vajpayee’s call to the nation On October 16, 1999. __________________________________________________________________ March 13, 2001: · Tehelka.com breaks a story that stuns the nation and the world. Tehelka investigators had captured on spy camera the president of the BJP, Bangaru Laxman, the Samata Party president, Jaya Jaitly (described as the ‘Second Defence Minister’ by one of the middlemen interviewed on videotape), and several top Defence Ministry officials accepting money, or showing willingness to accept money for defence deals. · This they had managed to do through a sting operation named Operation West End, posing as representatives of a fictitious UK based arms manufacturing firm. · Tehelka claims it paid out Rs. 10,80,000 in bribes to a cast of 34 characters. · Among the shots forming part of the four-and-a-half hour documentary are those of Bangaru Laxman accepting one lakh and asking for the promised five lakhs in dollars! He did not deny accepting the money. Bangaru Laxman resigns as BJP president. · Even before screening of the tapes at a press conference at a leading hotel here was over, the issue rocked both Houses of Parliament forcing their adjournment with the opposition demanding an immediate government statement on the issue. · The Union government says it is prepared for an inquiry into the tehelka.com expose of the alleged involvement of top politicians and government officials in corrupt defence deals. At an emergency Union Cabinet meeting George Fernandes reportedly offers to resign but the offer is rejected by the Prime Minister. -

TIGERLINK from the Director's Desk

May 2014, Revived Volume 15 TIGERLINK From the Director's Desk ......... 1 A Network of Concerned People and Organisations Across the Globe to Save the Tiger Editorial ......... 2 National News ......... 3 NEWS Focus ......... 8 REVIVED VOL-15 MAY-2014 News from the States ......... 20 Ranthambhore Foundation ......... 27 Dear friends, save their habitats, which are under a lot of RBS 'Earth Heroes' Awards ......... 31 pressure. No one can question the fact that the principle and International News ......... 45 ethics of wildlife conservation in Indian politics All common-property land in India has now been Wildlife Crime ......... 52 began with Smt Indira Gandhi. Her son, Rajiv consumed and exhausted by human exploitation. Gandhi, who shared her personal love for wildlife, The only land left to exploit is forest land. How Science & Research ......... 56 contributed while he was Prime Minister. At least much of this will the new government spare? Awards ......... 57 environment could find mention in the Congress As we go to press, there is bad news from Manas Media & Books ......... 58 manifesto, and for the first time, in 1984, in the national budget. Tiger Reserve, once one of our finest reserves, and now threatened by the increasing unrest in the After thier tenure, we saw zero political will region, and the consequent lack of support. towards wildlife conservation for a long time. Conservationists have raised an alarm over the situation in Manas and called for securing the Over the past ten years, i.e., both terms of the UPA, reserve, which Ranthmabhore Foundation fully we have seen tremendous slide in this priority for endorses. -

Westminsterresearch Bombay Before Bollywood

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Bombay before Bollywood: the history and significance of fantasy and stunt film genres in Bombay cinema of the pre- Bollywood era Thomas, K. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Prof Katharine Thomas, 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] BOMBAY BEFORE BOLLYWOOD: THE HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE OF FANTASY AND STUNT FILM GENRES IN BOMBAY CINEMA OF THE PRE-BOLLYWOOD ERA KATHARINE ROSEMARY CLIFTON THOMAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University Of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Published Work September 2016 Abstract This PhD by Published Work comprises nine essays and a 10,000-word commentary. Eight of these essays were published (or republished) as chapters within my monograph Bombay Before Bollywood: Film City Fantasies, which aimed to outline the contours of an alternative history of twentieth-century Bombay cinema. The ninth, which complements these, was published in an annual reader. This project eschews the conventional focus on India’s more respectable genres, the so-called ‘socials’ and ‘mythologicals’, and foregrounds instead the ‘magic and fighting films’ – the fantasy and stunt genres – of the B- and C-circuits in the decades before and immediately after India’s independence. -

Siyahi-Catalogue-2015-16.Pdf

Siyahi, in Urdu means ‘ink’, the dye that stains the shape of our thoughts. Tell us your story. And we’ll help you tell it to the world. Here at Siyahi, we’re with you right from the beginning. From assessing and editing the manuscript to finding the right publisher and promoting the book after publication, we stand firm by our authors through it all. While we deal primarily with manuscripts in English, we are actively involved in facilitating translation of books to and from various languages. We also organize literary events – everything from intimate readings to international literary festivals. RIGHTS LIST ALL RIGHTS AVAILABLE WORLD RIGHTS AVAILABLE LANGUAGE RIGHTS AVAILBLE AUTHORS FORTHCOMING PUBLISHED EVENTS TEAM RIGHTS LIST ALL RIGHTS AVAILABLE FICTION All Our Days by Keya Ghosh An Excess of Sanity by Anshumani Ruddra In Another Time by Keya Ghosh Indophrenia by Sudeep Chakravarti Men Without God by Meghna Pant Mohini’s Wedding by Selina Hossain (English Translation by Arunava Sinha) No More Tomorrows by Keya Ghosh Poskem by Wendell Rodricks The Ceaseless Chatter of Demons by Ashok Ferrey You Who Never Arrived by Anshumani Ruddra NON-FICTION Dream Catchers: Business Innovators of Bollywood by Priyanka Sinha Jha Dream Moghuls: Business Leaders of Bollywood by Priyanka Sinha Jha Folk Music and Musical Instruments of Punjab by Alka Pande Indian Street Food by Rocky Singh, Mayur Sharma Like Cotton from the Kapok Tree by Kalpana Mohan Managing Success...and Some Seriously Good Food by Rocky Singh, Mayur Sharma Magician in the Desert -

Research Update (July-Dec 2020)

Azim Premji University Research Update (July-Dec 2020) 1 Note from the Research Centre 2020 has been one of the most difficult of years. It was listed by the UN as the “International Year of Plant Health” and by the World Health Organization as the “Year of the Nurse and Midwife”. Sadly, the main thing the year will be remembered for is the COVID-19 Pandemic. As the year draws to an end, it is time for us to look forth with hope and expectation to a very different 2021. For the past two years, Azim Premji University has brought out a newsletter at regular intervals, to keep us updated on the research we collectively conduct. What started as a simple exercise of collation became more than a summary, as we experimented with different sections, and added new formats. As 2020 draws to a close, we have changed the format to a ‘magazine-like’ version. In this issue, you will find the regular newsletter coverage of articles, journal papers, research, etc. In addition, you will also find a new thematic focus: with some crystal ball-gazing into the future, we collectively engage in “Heralding 2021”. We have tried to make it as readable and visually rich as possible. As said earlier, we are evolving with time, and if you have any comments to share on the content, format or look n feel, do drop us a mail on [email protected] In the end, as we ring in the new year – 2021, declared as the “International Year of Peace and Trust,” and “the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development” by the UN, one can only hope and pray that it does not get stamped by one label or defined by one trend. -

32. Film Review.Pmd

FILM REVIEW supposedly gives them an edge over other ordinary riff-raff also trying to The Electric Moon emulate the white sahibs. The two brothers and the sister by belong to an impoverished erstwhile Madhu Kishwar royal family, now reduced to selling themselves, their past and their privacy To an audience addicted to soppy, demeaning interaction between the to the foreigners who have come to sentimental, “permanently - and - people of the arrogantly dominant India in search of the Oriental mystique thoroughly - good - guys versus West and the grovelling Third World. — tigers, turbans, maharajas, snake permanently - and- irredeemably - bad The film does not have much of a charmers and the like and ‘an-easy-to- - guys” format of Indian cinema, this is conventional “story” — but is an digest dose of India’s poverty.’ What bound to present itself as a disturbing unfolding of characters through a was once probably the erstwhile film. At the Bangalore film festival the series of encounters. In the forests of maharaja’s es•tate, is now a “national director Pradip Krishen and script- Central India there is an expensive park”—in other words — property writer Arundhati Roy were flooded jungle lodge called the Machan which forcibly taken over by the Government with a barrage of hostile questions: caters exclusively to foreign tourists. and “managed” in characteristic “How dare you present Indians in such Desi elite are simply not allowed even rapacious and red tapist style by a bad light?”, “It will harm the national if they are willing to pay as much as sarkari babus. -

Arundhati Roy Although I Do Not Believe That Awards Are a Measure

11 Arundhati Roy Although I do not believe that awards are a measure of the work we do, I would like to add the National Award for the Best Screenplay that I won in 1989 to the growing pile of returned awards. Also, I want to make it clear that I am not returning this award because I am “shocked” by what is being called the “growing intolerance” being fostered by the present government. First of all, “intolerance” is the wrong word to use for the lynching, shooting, burning and mass murder of fellow human beings. Second, we had plenty of advance notice of what lay in store for us—so I cannot claim to be shocked by what has happened after this government was enthusiastically voted into office with an overwhelming majority. Third, these horrific murders are only a symptom of a deeper malaise. Life is hell for the living too. Whole populations—millions of Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims and Christians are being forced to live in terror, unsure of when and from where the assault will come. Today we live in a country in which, when the thugs and apparatchiks of the New Order talk of “illegal slaughter” they mean the imaginary cow that was killed—not the real man that was murdered. When they talk of taking “evidence for forensic examination” from the scene of the crime, they mean the food in the fridge, not the body of the lynched man. We say we have “progressed”—but when Dalits are butchered and their children burned alive, which writer today can freely say, like Babasaheb Ambedkar once did that “To the Untouchables, Hinduism is a veritable chamber of horrors,” (Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches, Volume 9 pg 296) without getting attacked, lynched, shot or jailed? Which writer can write what Saadat Hassan Manto wrote in his “Letter to Uncle Sam”? It doesn’t matter whether we agree or disagree with what is being said. -

635301449163371226 IIC ANNUAL REPORT 2013-14 5-3-2014.Pdf

2013-2014 2013 -2014 Annual Report IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 2013-2014 IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna Professor M.G.K. Menon Mr. L.K. Joshi Dr. (Smt.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. N. N. Vohra Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Professor Dinesh Singh Mr. K. Raghunath Dr. Biswajit Dhar Dr. (Ms) Sukrita Paul Kumar Cmde.(Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mrs. Meera Bhatia Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna, Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Chairman Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mr. M. Damodaran Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. Ashok K. Chopra, Chief Finance Officer Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. Gita Prakash Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar, Executive Chef Ms Premola Ghose, Chief, Programme Division Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief, Maintenance Division Ms Hema Gusain, Purchase Officer Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Ms Seema Kohli, Membership Officer Annual Report 2013-2014 It is a privilege to present the 53rd Annual Report of the India International Centre for the period 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2014. The Board of Trustees reconstituted the Finance Committee for the two-year period April 2013 to March 2015 with Justice B.N. -

Final Calendar Booklet.Cdr

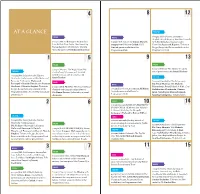

S4 T8 M12 AT A GLANCE THEATRE MUSIC MUSIC 8:00pm|Mera Bhaarat Pareshaan (English/Hindi/80mins) Standup Comedy 7:00pm|IHC Lok Sangeet Sammelan. 7:30pm|Sufi concert by Sanam Marvi & by Aditi Mittal and Varun Grover. Love Ballads From India - Pandavani by troupe from Pakistan Collab: ICCR Hosted by Rajneesh Kapoor. Tickets at Teejan Bai from Chattisgarh. Marathi Limited passes available at the Rs.350,Rs.250 and Rs.100 available at the Natya Sangeet by Dr.Suhasini Koratkar Programmes Desk. Programmes Desk T1 M5 F9 13T TALKS TALKS 7:00pm|Mozart: The Magic Flute (Die 7:00pm|Without The Lifeline An audio THEATRE Zauberfloete) (German with English visual presentation by Sohail Hashmi 7:00pm|New Tales from the Tilism-e subtitles/182mins) Introduction by THEATRE Hoshruba (Urdu/150mins) Dir.Mahmood Sunit Tandon Farooqui Performers: Mahmood 7:00pm|Atmakatha (Hindi/130mins) FILMS Farooqui & Danish Husain and Poonam MUSIC Dir.Vinay Sharma. Wri.Mahesh Girdhani & Namita Singhai. Tickets at 7:00pm|GUR PRASAD: The Grace Of Food Elkunchwar. Prod.Padatik & Rikh. Cast: 7:00pm|Sarod recital by Ayaan Ali Khan. Rs.350, Rs.250 & Rs.100 available at the (Punjabi with Eng sub-titles/58mins) Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Chetna Limited passes available at the Programmes Desk. An Old World Culture Dir.Meera Dewan. Followed by a panel Jalan, Sanchayita Bhattacharjee & Programmes Desk. presentation discussion Anubha Fatehpuria. Ticketed show. 2 6 TALKS 10 14 F T 9:30am-11:30am|HABITAT CHILDREN’SS W BOOK FORUM|Of Heroes And Villains - A Writers’ Workshop by Deepali Junjappa & Dalanglin Bryson Dkhar THEATRE FILMS 7:00pm|New Tales from the Tilism-e 10:00am onwards|A 2-day festival of THEATRE Hoshruba (Urdu/150mins) award winning documentaries by Public TALKS 7:00pm|Atmakatha (Hindi/130mins) Dir.Mahmood Farooqui Performers: Service Broadcasting Trust Mahmood Farooqui & Danish 7:00pm|ILLUSTRATED TALK|Raj, Samaj Dir.Vinay Sharma.