Whole Exome Sequencing Reveals NOTCH1 Mutations in Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma and Points to Notch Both As a Key Pathway and a Potential Therapeutic Target

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title a New Centrosomal Protein Regulates Neurogenesis By

Title A new centrosomal protein regulates neurogenesis by microtubule organization Authors: Germán Camargo Ortega1-3†, Sven Falk1,2†, Pia A. Johansson1,2†, Elise Peyre4, Sanjeeb Kumar Sahu5, Loïc Broic4, Camino De Juan Romero6, Kalina Draganova1,2, Stanislav Vinopal7, Kaviya Chinnappa1‡, Anna Gavranovic1, Tugay Karakaya1, Juliane Merl-Pham8, Arie Geerlof9, Regina Feederle10,11, Wei Shao12,13, Song-Hai Shi12,13, Stefanie M. Hauck8, Frank Bradke7, Victor Borrell6, Vijay K. Tiwari§, Wieland B. Huttner14, Michaela Wilsch- Bräuninger14, Laurent Nguyen4 and Magdalena Götz1,2,11* Affiliations: 1. Institute of Stem Cell Research, Helmholtz Center Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany. 2. Physiological Genomics, Biomedical Center, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, Germany. 3. Graduate School of Systemic Neurosciences, Biocenter, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, Germany. 4. GIGA-Neurosciences, Molecular regulation of neurogenesis, University of Liège, Belgium 5. Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB), Mainz, Germany. 6. Instituto de Neurociencias, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas and Universidad Miguel Hernández, Sant Joan d’Alacant, Spain. 7. Laboratory for Axon Growth and Regeneration, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), Bonn, Germany. 8. Research Unit Protein Science, Helmholtz Centre Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany. 9. Protein Expression and Purification Facility, Institute of Structural Biology, Helmholtz Center Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany. 10. Institute for Diabetes and Obesity, Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility, Helmholtz Center Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany. 11. SYNERGY, Excellence Cluster of Systems Neurology, Biomedical Center, Ludwig- Maximilian University Munich, Germany. 12. Developmental Biology Program, Sloan Kettering Institute, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA 13. -

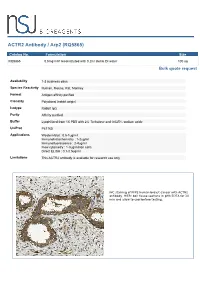

ACTR2 Antibody / Arp2 (RQ5865)

ACTR2 Antibody / Arp2 (RQ5865) Catalog No. Formulation Size RQ5865 0.5mg/ml if reconstituted with 0.2ml sterile DI water 100 ug Bulk quote request Availability 1-3 business days Species Reactivity Human, Mouse, Rat, Monkey Format Antigen affinity purified Clonality Polyclonal (rabbit origin) Isotype Rabbit IgG Purity Affinity purified Buffer Lyophilized from 1X PBS with 2% Trehalose and 0.025% sodium azide UniProt P61160 Applications Western blot : 0.5-1ug/ml Immunohistochemistry : 1-2ug/ml Immunofluorescence : 2-4ug/ml Flow cytometry : 1-3ug/million cells Direct ELISA : 0.1-0.5ug/ml Limitations This ACTR2 antibody is available for research use only. IHC staining of FFPE human breast cancer with ACTR2 antibody. HIER: boil tissue sections in pH8 EDTA for 20 min and allow to cool before testing. Immunofluorescent staining of FFPE human A549 cells with ACTR2 antibody (green) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue). HIER: steam section in pH6 citrate buffer for 20 min. Western blot testing of 1) rat kidney, 2) rat spleen, 3) mouse HEPA1-6, 4) mouse SP2/0, 5) monkey COS-7 and human 6) U-87 MG, 7) Jurkat, 8) PC-3 and 9) U-2 OS lysate with ACTR2 antibody. Predicted molecular weight ~45 kDa. Flow cytometry testing of human A431 cells with ACTR2 antibody at 1ug/million cells (blocked with goat sera); Red=cells alone, Green=isotype control, Blue= ACTR2 antibody. Flow cytometry testing of mouse ANA-1 cells with ACTR2 antibody at 1ug/million cells (blocked with goat sera); Red=cells alone, Green=isotype control, Blue= ACTR2 antibody. Description The specific function of this gene has not yet been determined; however, the protein it encodes is known to be a major constituent of the ARP2/3 complex. -

Prioritization and Evaluation of Depression Candidate Genes by Combining Multidimensional Data Resources

Prioritization and Evaluation of Depression Candidate Genes by Combining Multidimensional Data Resources Chung-Feng Kao1, Yu-Sheng Fang2, Zhongming Zhao3, Po-Hsiu Kuo1,2,4* 1 Department of Public Health and Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2 Institute of Clinical Medicine, School of Medicine, National Cheng-Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 3 Departments of Biomedical Informatics and Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, United States of America, 4 Research Center for Genes, Environment and Human Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan Abstract Background: Large scale and individual genetic studies have suggested numerous susceptible genes for depression in the past decade without conclusive results. There is a strong need to review and integrate multi-dimensional data for follow up validation. The present study aimed to apply prioritization procedures to build-up an evidence-based candidate genes dataset for depression. Methods: Depression candidate genes were collected in human and animal studies across various data resources. Each gene was scored according to its magnitude of evidence related to depression and was multiplied by a source-specific weight to form a combined score measure. All genes were evaluated through a prioritization system to obtain an optimal weight matrix to rank their relative importance with depression using the combined scores. The resulting candidate gene list for depression (DEPgenes) was further evaluated by a genome-wide association (GWA) dataset and microarray gene expression in human tissues. Results: A total of 5,055 candidate genes (4,850 genes from human and 387 genes from animal studies with 182 being overlapped) were included from seven data sources. -

Tumor Initiating but Differentiated Luminal-Like Breast Cancer Cells Are Highly Invasive in the Absence of Basal-Like Activity

Tumor initiating but differentiated luminal-like breast cancer cells are highly invasive in the absence of basal-like activity Jiyoung Kima, René Villadsena, Therese Sørlieb,c, Louise Fogha, Signe Z. Grønlunda,d, Agla J. Fridriksdottira, Irene Kuhne, Fritz Rankf,1, Vera Timmermans Wielengaf, Hiroko Solvangb,g, Paul A. W. Edwardsh, Anne-Lise Børresen-Daleb,i, Lone Rønnov-Jessend, Mina J. Bisselle,2, and Ole William Petersena,2 aDepartment of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Centre for Biological Disease Analysis and Danish Stem Cell Centre, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, DK-2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark; bDepartment of Genetics, Institute for Cancer Research, Oslo University Hospital Radiumhospitalet, Montebello 0310, Oslo, Norway; cCancer Stem Cell Innovation Center, Oslo University Hospital, Norwegian Radium Hospital, 0310 Oslo, Norway; dCell and Developmental Biology, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark; eLife Sciences Division, Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720; fDepartment of Pathology, Rigshospitalet, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark; gDepartment of Biostatistics, Institute of Basic Medical Science, University of Oslo, 0317 Oslo, Norway; hDepartment of Pathology and Hutchison/MRC Research Centre, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 0X2, United Kingdom; and iK. G. Jebsen Center for Breast Cancer Research, Institute for Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, 0318 Oslo, Norway Contributed by Mina J. Bissell, February 28, 2012 (sent for review January 10, 2012) The majority of human breast cancers exhibit luminal epithelial these contradictions is the concept of tumor cell plasticity, i.e., the differentiation. However, most aggressive behavior, including possibility that differentiated luminal cells must acquire basal-like invasion and purported cancer stem cell activity, are considered traits to become malignant (10–14). -

Synergistic Genetic Interactions Between Pkhd1 and Pkd1 Result in an ARPKD-Like Phenotype in Murine Models

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Synergistic Genetic Interactions between Pkhd1 and Pkd1 Result in an ARPKD-Like Phenotype in Murine Models Rory J. Olson,1 Katharina Hopp ,2 Harrison Wells,3 Jessica M. Smith,3 Jessica Furtado,1,4 Megan M. Constans,3 Diana L. Escobar,3 Aron M. Geurts,5 Vicente E. Torres,3 and Peter C. Harris 1,3 Due to the number of contributing authors, the affiliations are listed at the end of this article. ABSTRACT Background Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) are genetically distinct, with ADPKD usually caused by the genes PKD1 or PKD2 (encoding polycystin-1 and polycystin-2, respectively) and ARPKD caused by PKHD1 (encoding fibrocys- tin/polyductin [FPC]). Primary cilia have been considered central to PKD pathogenesis due to protein localization and common cystic phenotypes in syndromic ciliopathies, but their relevance is questioned in the simple PKDs. ARPKD’s mild phenotype in murine models versus in humans has hampered investi- gating its pathogenesis. Methods To study the interaction between Pkhd1 and Pkd1, including dosage effects on the phenotype, we generated digenic mouse and rat models and characterized and compared digenic, monogenic, and wild-type phenotypes. Results The genetic interaction was synergistic in both species, with digenic animals exhibiting pheno- types of rapidly progressive PKD and early lethality resembling classic ARPKD. Genetic interaction be- tween Pkhd1 and Pkd1 depended on dosage in the digenic murine models, with no significant enhancement of the monogenic phenotype until a threshold of reduced expression at the second locus was breached. -

Gene Regulation and Speciation in House Mice

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 26, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Gene regulation and speciation in house mice Katya L. Mack,1 Polly Campbell,2 and Michael W. Nachman1 1Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3160, USA; 2Department of Integrative Biology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078, USA One approach to understanding the process of speciation is to characterize the genetic architecture of post-zygotic isolation. As gene regulation requires interactions between loci, negative epistatic interactions between divergent regulatory elements might underlie hybrid incompatibilities and contribute to reproductive isolation. Here, we take advantage of a cross between house mouse subspecies, where hybrid dysfunction is largely unidirectional, to test several key predictions about regulatory divergence and reproductive isolation. Regulatory divergence between Mus musculus musculus and M. m. domesticus was charac- terized by studying allele-specific expression in fertile hybrid males using mRNA-sequencing of whole testes. We found ex- tensive regulatory divergence between M. m. musculus and M. m. domesticus, largely attributable to cis-regulatory changes. When both cis and trans changes occurred, they were observed in opposition much more often than expected under a neutral model, providing strong evidence of widespread compensatory evolution. We also found evidence for lineage-specific positive se- lection on a subset of genes related to transcriptional regulation. Comparisons of fertile and sterile hybrid males identified a set of genes that were uniquely misexpressed in sterile individuals. Lastly, we discovered a nonrandom association between these genes and genes showing evidence of compensatory evolution, consistent with the idea that regulatory interactions might contribute to Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities and be important in speciation. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Location Analysis of Estrogen Receptor Target Promoters Reveals That

Location analysis of estrogen receptor ␣ target promoters reveals that FOXA1 defines a domain of the estrogen response Jose´ e Laganie` re*†, Genevie` ve Deblois*, Ce´ line Lefebvre*, Alain R. Bataille‡, Franc¸ois Robert‡, and Vincent Gigue` re*†§ *Molecular Oncology Group, Departments of Medicine and Oncology, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada H3A 1A1; †Department of Biochemistry, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada H3G 1Y6; and ‡Laboratory of Chromatin and Genomic Expression, Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montre´al, Montreal, QC, Canada H2W 1R7 Communicated by Ronald M. Evans, The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA, July 1, 2005 (received for review June 3, 2005) Nuclear receptors can activate diverse biological pathways within general absence of large scale functional data linking these putative a target cell in response to their cognate ligands, but how this binding sites with gene expression in specific cell types. compartmentalization is achieved at the level of gene regulation is Recently, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) has been used poorly understood. We used a genome-wide analysis of promoter in combination with promoter or genomic DNA microarrays to occupancy by the estrogen receptor ␣ (ER␣) in MCF-7 cells to identify loci recognized by transcription factors in a genome-wide investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the action of manner in mammalian cells (20–24). This technology, termed 17-estradiol (E2) in controlling the growth of breast cancer cells. ChIP-on-chip or location analysis, can therefore be used to deter- We identified 153 promoters bound by ER␣ in the presence of E2. mine the global gene expression program that characterize the Motif-finding algorithms demonstrated that the estrogen re- action of a nuclear receptor in response to its natural ligand. -

Alagille Watson Syndrome (JAG1) Sequencing & Deletion/Duplication

Lab Dept: Anatomic Pathology Test Name: ALAGILLE WATSON SYNDROME (JAG1) SEQUENCING General Information Lab Order Codes: JAG1 Synonyms: Alagille Watson Syndrome; Cholestasis with Peripheral Pulmonary Stenosis; Arteriohepatic Dysplasia; Syndromatic Hepatic Ductular Hypoplasia; ALGS1 CPT Codes: Sequencing: 81407 – Molecular pathology Level 8 Deletion/Duplication- High Density Targeted Array 81406 – Molecular pathology Level 7 Test Includes: Analysis of bi-directional sequencing. Also includes a targeted array CGH analysis with exon-level resolution to evaluate for a deletion or duplication of one exon of this gene. Logistics Test Indications: Alagille Syndrome is one of the major forms of chronic liver disease in children and is an autosomal dominant disorder with high penetrance but variable expressivity. The main clinical findings include cholestatis due to bile duct paucity, a characteristic facial appearance, and cardiovascular, eye and skeletal abnormalities. Cardiovascular findings include tetralogy of Fallot or singular manifestations thereof, peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis, atrial and/or ventricular septal defects, and coarction of the aorta. Butterfly vertebra is the most common skeletal finding. Other findings include narrowing of interpeduncular spaces in the lumbar spine, spina bifida occulta, and short fingers and ulnae. Facial features consist of broad forehead, triangular face, prominent zygomatic arch and moderate hypertelorism. Posterior embryotoxon and retinal pigmentary changes are common opthalmological findings. ALGS1 is caused by mutations in the JAG1 gene. It encodes jagged-1, a ligand for the Notch receptors. Notch proteins are transmembrane receptors and are components of signaling pathways important for cell fate. JAG1 is expressed in the developing heart and other structures affected in Alagille syndrome. Over 90% of patients with Alagille syndrome have a mutation in the JAG1 gene. -

Epigenome-Wide Exploratory Study of Monozygotic Twins Suggests Differentially Methylated Regions to Associate with Hand Grip Strength

Biogerontology (2019) 20:627–647 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-019-09818-1 (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) RESEARCH ARTICLE Epigenome-wide exploratory study of monozygotic twins suggests differentially methylated regions to associate with hand grip strength Mette Soerensen . Weilong Li . Birgit Debrabant . Marianne Nygaard . Jonas Mengel-From . Morten Frost . Kaare Christensen . Lene Christiansen . Qihua Tan Received: 15 April 2019 / Accepted: 24 June 2019 / Published online: 28 June 2019 Ó The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Hand grip strength is a measure of mus- significant CpG sites or pathways were found, how- cular strength and is used to study age-related loss of ever two of the suggestive top CpG sites were mapped physical capacity. In order to explore the biological to the COL6A1 and CACNA1B genes, known to be mechanisms that influence hand grip strength varia- related to muscular dysfunction. By investigating tion, an epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) of genomic regions using the comb-p algorithm, several hand grip strength in 672 middle-aged and elderly differentially methylated regions in regulatory monozygotic twins (age 55–90 years) was performed, domains were identified as significantly associated to using both individual and twin pair level analyses, the hand grip strength, and pathway analyses of these latter controlling the influence of genetic variation. regions revealed significant pathways related to the Moreover, as measurements of hand grip strength immune system, autoimmune disorders, including performed over 8 years were available in the elderly diabetes type 1 and viral myocarditis, as well as twins (age 73–90 at intake), a longitudinal EWAS was negative regulation of cell differentiation. -

Supplemental Table 1. Complete Gene Lists and GO Terms from Figure 3C

Supplemental Table 1. Complete gene lists and GO terms from Figure 3C. Path 1 Genes: RP11-34P13.15, RP4-758J18.10, VWA1, CHD5, AZIN2, FOXO6, RP11-403I13.8, ARHGAP30, RGS4, LRRN2, RASSF5, SERTAD4, GJC2, RHOU, REEP1, FOXI3, SH3RF3, COL4A4, ZDHHC23, FGFR3, PPP2R2C, CTD-2031P19.4, RNF182, GRM4, PRR15, DGKI, CHMP4C, CALB1, SPAG1, KLF4, ENG, RET, GDF10, ADAMTS14, SPOCK2, MBL1P, ADAM8, LRP4-AS1, CARNS1, DGAT2, CRYAB, AP000783.1, OPCML, PLEKHG6, GDF3, EMP1, RASSF9, FAM101A, STON2, GREM1, ACTC1, CORO2B, FURIN, WFIKKN1, BAIAP3, TMC5, HS3ST4, ZFHX3, NLRP1, RASD1, CACNG4, EMILIN2, L3MBTL4, KLHL14, HMSD, RP11-849I19.1, SALL3, GADD45B, KANK3, CTC- 526N19.1, ZNF888, MMP9, BMP7, PIK3IP1, MCHR1, SYTL5, CAMK2N1, PINK1, ID3, PTPRU, MANEAL, MCOLN3, LRRC8C, NTNG1, KCNC4, RP11, 430C7.5, C1orf95, ID2-AS1, ID2, GDF7, KCNG3, RGPD8, PSD4, CCDC74B, BMPR2, KAT2B, LINC00693, ZNF654, FILIP1L, SH3TC1, CPEB2, NPFFR2, TRPC3, RP11-752L20.3, FAM198B, TLL1, CDH9, PDZD2, CHSY3, GALNT10, FOXQ1, ATXN1, ID4, COL11A2, CNR1, GTF2IP4, FZD1, PAX5, RP11-35N6.1, UNC5B, NKX1-2, FAM196A, EBF3, PRRG4, LRP4, SYT7, PLBD1, GRASP, ALX1, HIP1R, LPAR6, SLITRK6, C16orf89, RP11-491F9.1, MMP2, B3GNT9, NXPH3, TNRC6C-AS1, LDLRAD4, NOL4, SMAD7, HCN2, PDE4A, KANK2, SAMD1, EXOC3L2, IL11, EMILIN3, KCNB1, DOK5, EEF1A2, A4GALT, ADGRG2, ELF4, ABCD1 Term Count % PValue Genes regulation of pathway-restricted GDF3, SMAD7, GDF7, BMPR2, GDF10, GREM1, BMP7, LDLRAD4, SMAD protein phosphorylation 9 6.34 1.31E-08 ENG pathway-restricted SMAD protein GDF3, SMAD7, GDF7, BMPR2, GDF10, GREM1, BMP7, LDLRAD4, phosphorylation -

CRAVAT 4: Cancer-Related Analysis of Variants Toolkit David L

Cancer Focus on Computer Resources Research CRAVAT 4: Cancer-Related Analysis of Variants Toolkit David L. Masica1,2, Christopher Douville1,2, Collin Tokheim1,2, Rohit Bhattacharya2,3, RyangGuk Kim4, Kyle Moad4, Michael C. Ryan4, and Rachel Karchin1,2,5 Abstract Cancer sequencing studies are increasingly comprehensive and level interpretation, including joint prioritization of all nonsilent well powered, returning long lists of somatic mutations that can be mutation consequence types, and structural and mechanistic visu- difficult to sort and interpret. Diligent analysis and quality control alization. Results from CRAVAT submissions are explored in an can require multiple computational tools of distinct utility and interactive, user-friendly web environment with dynamic filtering producing disparate output, creating additional challenges for the and sorting designed to highlight the most informative mutations, investigator. The Cancer-Related Analysis of Variants Toolkit (CRA- even in the context of very large studies. CRAVAT can be run on a VAT) is an evolving suite of informatics tools for mutation inter- public web portal, in the cloud, or downloaded for local use, and is pretation that includes mutation mapping and quality control, easily integrated with other methods for cancer omics analysis. impact prediction and extensive annotation, gene- and mutation- Cancer Res; 77(21); e35–38. Ó2017 AACR. Background quickly returning mutation interpretations in an interactive and user-friendly web environment for sorting, visualizing, and An investigator's work is far from over when results are returned inferring mechanism. CRAVAT (see Supplementary Video) is from the sequencing center. Depending on the service, genetic suitable for large studies (e.g., full-exome and large cohorts) mutation calls can require additional mapping to include all and small studies (e.g., gene panel or single patient), performs relevant RNA transcripts or correct protein sequences.