Health and Welfare in Dutch Organic Laying Hens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Luis Obispo County 4-H Youth Development Program

SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY 4-H YOUTH DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM POULTRY LEVEL TEST STUDY GUIDE LEVELS I & II Passing Score for Level I is 50%, Passing Score for Level II is 75% FEEDS YOU SHOULD RECOGNIZE: Broiler Mash Lay Pellets Pigeon Feed Cracked Corn Lay Crumbles Rolled Oats Hen Scratch Milo Turkey Game and Grower Grit Oyster Shell Whole Corn POULTRY EQUIPMENT YOU SHOULD KNOW: Antibiotic-Water Soluble Electrolyte Solution Net Antibiotic-Injectable Feeder Poultry Dust Brooder Heat Lamp Waterer Egg Basket Incubator Wormer-Water Soluble Egg Candler Leg Bands Egg Scale Nest Eggs POULTRY BODY PARTS YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY: Back (Cape) Saddle Sickles Points Ear Blade Wattles Beak Comb Breast Body Hackle Eye Ear Lobes Primaries Main Sickles Lesser Sickles Saddle Feathers Fluff Shank Spur Claw Hock Thigh Secondaries Wing Bar Wing Bow STUDY GUIDE LEVELS ONE AND TWO Page 1 of 11 Revised 09/2008 BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY THE FOLLOWING TYPES OF STANDARD MALE COMBS (Level I & II) Single Comb Rose Comb Pea Comb Cushion Comb Buttercup Comb Strawberry Comb V- Comb (Sultans) BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY THE PARTS OF THE MALE CHICKEN (Level I) STUDY GUIDE LEVELS ONE AND TWO Page 2 of 11 Revised 09/2008 BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY THE PARTS OF THE FEATHER (Level I) Shaft Web Fluff Quill BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY THE PARTS OF THE EGG (Level II) 1. Cuticle 2. Shell 3. Yolk 4. Chalazae 5. Germinal Disc 6. Albumen 7. Air Cell STUDY GUIDE LEVELS ONE AND TWO Page 3 of 11 Revised 09/2008 BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY THE INTERNAL ORGANS (Level II) Lung Gizzard Crop Kidney Liver Esophagus Intestine Heart Trachea STUDY GUIDE LEVELS ONE AND TWO Page 4 of 11 Revised 09/2008 BE ABLE TO IDENTIFY THE PARTS OF THE WING (Level II) 1. -

Guidance for Assessing Animal Welfare on Organic Sheep Operations

National Organic Standards Board Livestock Committee Proposed Discussion Document March 28, 2012 Guidance for Assessing Animal Welfare on Organic Poultry Operations The following is provided to aid in assessment of whether or not the requirements of § 205.238-241 are being met sufficiently to demonstrate adequate animal welfare conditions on organic poultry operations. In addition, this document provides further guidance to producers for improving poultry welfare. The internationally recognized “five freedoms” (freedom from hunger, thirst and malnutrition; freedom from fear and distress; freedom from physical and thermal discomfort; freedom from pain, injury and disease; and freedom to express normal patterns of behavior) promulgated by the Farm Animal Welfare Council are a useful framework for considering animal welfare. Nutritional requirements Poultry must be fed a wholesome diet that meets their nutritional needs and promotes optimal health. Feed should be formulated to meet or exceed the National Research Council’s Nutrient Requirements of Poultry, and adjusted with bird age and stage of production. Feed and water should be palatable and free from contaminants. Unless using a commercially prepared complete feed, laying hens must have access to a course calcium source, such as ground limestone. Water should be fresh, potable, and clean. Feed and water delivery systems should be checked daily and kept clean and in good working order. Birds must be provided with feed on a daily basis and water should be available continuously, with the rare exception of withholding for medical treatment under the advice of a veterinarian. There should be enough feed and water space to prevent competition between birds. -

ISAE 2014.Pdf

edited by: Inma Estevez, Xavier Manteca, Raul H. Marin and Xavier Averós Applied ethology 2014: Moving on ISAE2014 Proceedings of the 48th Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology 29 July – 2 August 2014, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain Moving on edited by: Inma Estevez Xavier Manteca Raul H. Marin Xavier Averós Wageningen Academic Publishers Buy a print copy of this book at: www.WageningenAcademic.com/ISAE2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned. Nothing from this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a computerised system or published in any form or in any manner, including electronic, mechanical, reprographic or photographic, without prior written permission from the publisher: Wageningen Academic Publishers P.O. Box 220 EAN: 9789086862450 6700 AE Wageningen e-EAN: 9789086867974 The Netherlands ISBN: 978-90-8686-245-0 www.WageningenAcademic.com e-ISBN: 978-90-8686-797-4 [email protected] DOI: 10.3920/978-90-8686-797-4 The individual contributions in this publication and any liabilities arising from them remain First published, 2014 the responsibility of the authors. The publisher is not responsible for possible © Wageningen Academic Publishers damages, which could be a result of content The Netherlands, 2014 derived from this publication. Welcome to the 48th Congress of the ISAE What makes science most exciting is not how much you know, but how much you can still learn, widening the possibilities of exploring new horizons. In this learning process diversity of experiences, exposure to new ideas, concepts or methodologies enrich and expand our capacity for innovation. -

Cannibalism in Extensive Poultry Keeping: Interfacing Genetics and Welfare

CANNIBALISM IN EXTENSIVE POULTRY KEEPING: INTERFACING GENETICS AND WELFARE PaulKoene Department of Animal Sciences, Ethology Group, Wageningen Agricultural University, Marijkeweg 40, P.O. box 338, 6700 AH Wageningen, the Netherlands, [email protected], http://www.zod.wau.nl/~www-vh/etho SUMMARY Cannibalism frequently occurs in free-range poultry keeping. An inventory in the Netherlands showed the severity of the problem. Also in our neighbouring countries the problem of cannibalism is found. A short literature review showed that a wealth of factors - environmental, ontogenetical and genetical - may play a role in the development of cannibalism. The most promising way to reach a solution seems to be to adapt the animal to its - free-range - environment. Heritability estimates of feather pecking and cannibalism are reasonably high. Especially the molecular genetical analysis together with ethological analysis can show the genetic background (markers or even genes) that is responsible for the cannibalism. Selection against this vice must be feasible. Keywords: cannibalism, genetics, selection, welfare, Gallus domesticus INTRODUCTION The objective of this study is to determine the best way to diminish cannibalism in extensive poultry keeping (free-range hens) by adapting the bird to the free-range environment (Faure, 1980), where adapting the environment to the bird seems to have failed concerning animal welfare. Different breeding and selection strategies will be presented dependent on welfare criteria, rather than on production criteria. Extensive poultry keeping. The goal of free-range laying hen keeping is to provide the consumer with an animal-friendly egg from hens kept under animal-friendly conditions. During the last 40 years breeding programs were directed at intensive husbandry systems and changed markedly the genotypes of the animals involved. -

Poultry Industry Manual

POULTRY INDUSTRY MANUAL FAD PReP Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness & Response Plan National Animal Health Emergency Management System United States Department of Agriculture • Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service • Veterinary Services MARCH 2013 Poultry Industry Manual The Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP)/National Animal Health Emergency Management System (NAHEMS) Guidelines provide a framework for use in dealing with an animal health emergency in the United States. This FAD PReP Industry Manual was produced by the Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University of Science and Technology, College of Veterinary Medicine, in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service through a cooperative agreement. The FAD PReP Poultry Industry Manual was last updated in March 2013. Please send questions or comments to: Center for Food Security and Public Health National Center for Animal Health 2160 Veterinary Medicine Emergency Management Iowa State University of Science and Technology US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Ames, IA 50011 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Telephone: 515-294-1492 U.S. Department of Agriculture Fax: 515-294-8259 4700 River Road, Unit 41 Email: [email protected] Riverdale, Maryland 20737-1231 subject line FAD PReP Poultry Industry Manual Telephone: (301) 851-3595 Fax: (301) 734-7817 E-mail: [email protected] While best efforts have been used in developing and preparing the FAD PReP/NAHEMS Guidelines, the US Government, US Department of Agriculture and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and other parties, such as employees and contractors contributing to this document, neither warrant nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information or procedure disclosed. -

Performance of Laying Hens in a Cognitive Bias Task; the Effect of Time Since Change of Environment

Performance of laying hens in a cognitive bias task; the effect of time since change of environment Kognitiv förskjutning hos värphönor; effekten av förfluten tid sedan miljöbyte Lena Lindström Etologi och djurskyddsprogrammet ______________________________________________________________________________ Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Skara 2010 Studentarbete 189 Institutionen för husdjurens miljö och hälsa Etologi och djurskyddsprogrammet Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Student report 189 Department of Animal Environment and Health Ethology and Animal Welfare programme ISSN 1652-280X Performance of laying hens in a cognitive bias task; the effect of time since change of environment Kognitiv förskjutning hos värphönor; effekten av förfluten tid sedan miljöbyte Lena Lindström Studentarbete 189, Skara 2010 Grund C, 15 hp, Etologi och djurskyddsprogrammet, självständigt arbete i biologi, kurskod EX0293 Handledare: Jenny Loberg, institutionen för husdjurens miljö och hälsa, SLU Biträdande handledare: Anette Wichman, Köpenhamns universitet Examinator: Maria Andersson, institutionen för husdjurens miljö och hälsa, SLU Nyckelord: cognitive bias; laying hen; gallus gallus; animal behaviour; animal welfare Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Fakulteten för veterinärmedicin och husdjursvetenskap Institutionen för husdjurens miljö och hälsa Avdelningen för etologi och djurskydd Box 234, 532 23 SKARA E-post: [email protected], Hemsida: www.hmh.slu.se I denna serie publiceras olika typer av studentarbeten, bl.a. examensarbeten, vanligtvis omfattande -

Biological Sciences

A Comprehensive Book on Environmentalism Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction to Environmentalism Chapter 2 - Environmental Movement Chapter 3 - Conservation Movement Chapter 4 - Green Politics Chapter 5 - Environmental Movement in the United States Chapter 6 - Environmental Movement in New Zealand & Australia Chapter 7 - Free-Market Environmentalism Chapter 8 - Evangelical Environmentalism Chapter 9 -WT Timeline of History of Environmentalism _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Book on Enzymes Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction to Enzyme Chapter 2 - Cofactors Chapter 3 - Enzyme Kinetics Chapter 4 - Enzyme Inhibitor Chapter 5 - Enzymes Assay and Substrate WT _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Introduction to Bioenergy Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Bioenergy Chapter 2 - Biomass Chapter 3 - Bioconversion of Biomass to Mixed Alcohol Fuels Chapter 4 - Thermal Depolymerization Chapter 5 - Wood Fuel Chapter 6 - Biomass Heating System Chapter 7 - Vegetable Oil Fuel Chapter 8 - Methanol Fuel Chapter 9 - Cellulosic Ethanol Chapter 10 - Butanol Fuel Chapter 11 - Algae Fuel Chapter 12 - Waste-to-energy and Renewable Fuels Chapter 13 WT- Food vs. Fuel _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Introduction to Botany Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Botany Chapter 2 - History of Botany Chapter 3 - Paleobotany Chapter 4 - Flora Chapter 5 - Adventitiousness and Ampelography Chapter 6 - Chimera (Plant) and Evergreen Chapter -

British Poultry Standards

British Poultry Standards Complete specifi cations and judging points of all standardized breeds and varieties of poultry as compiled by the specialist Breed Clubs and recognised by the Poultry Club of Great Britain Sixth Edition Edited by Victoria Roberts BVSc MRCVS Honorary Veterinary Surgeon to the Poultry Club of Great Britain Council Member, Poultry Club of Great Britain This edition fi rst published 2008 © 2008 Poultry Club of Great Britain Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing programme has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered offi ce John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial offi ce 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, United Kingdom For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of the author to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. -

Unit 1 Breeds, Varieties and Strains

UNIT 1 BREEDS, VARIETIES AND STRAINS Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Origin of Fowl 1.3 Common Breeds of Poultry 1.3.1 Chicken 1.3.2 Duck 1.3.3 Emu 1.3.4 Geese 1.3.5 Guinea Fowl 1.3.6 Quail 1.3.7 Turkey 1.4 Let Us Sum Up 1.5 Glossary 1.6 Suggested Further Reading 1.7 References 1.8 Answers to Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVES After studying this unit, you will be able to: ””” describe the characteristics of common breeds, varieties and strains of poultry; ””” classify chicken based on their place of origin, commercial value and utility; ””” identify different breeds of chicken and duck; and ””” differentiate between egg and meat type birds. 1.1 INTRODUCTION During the past two centuries, more than 300 pure breeds and varieties of chicken have been developed. However, few have survived commercialization and are being used by modern chicken breeders; for instance White Leghorn, White Cornish, Red Cornish, New Hampshire etc. However, most of the other breeds are kept for exhibition purpose only; some have even been lost forever and others are maintained by private or Government breeding farms and are available to breeders, if necessary. 1.2 ORIGIN OF FOWL Domestication of poultry seems to have been undertaken in the south-east Asia. By 1000 BC, the chickens were brought to India and later on, they spread north, westwards and reached Greece by 525 BC. By the beginning of the Christian era, the birds were already popular in West Asia and East Europe, and then gradually reached South Africa, Australia, Japan, USSR and USA. -

The Development of a Predictive Model of Damaging Pecking in Laying Hens

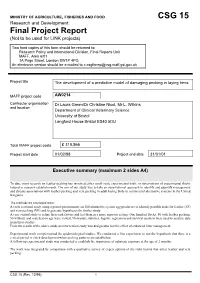

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FISHERIES AND FOOD CSG 15 Research and Development Final Project Report (Not to be used for LINK projects) Two hard copies of this form should be returned to: Research Policy and International Division, Final Reports Unit MAFF, Area 6/01 1A Page Street, London SW1P 4PQ An electronic version should be e-mailed to [email protected] Project title The development of a predictive model of damaging pecking in laying hens MAFF project code AW0214 Contractor organisation Dr Laura Green/Dr Christine Nicol, Mr L. Wilkins and location Department of Clinical Veterinary Science University of Bristol Langford House Bristol BS40 5DU Total MAFF project costs £ 318,566 Project start date 01/02/98 Project end date 31/01/01 Executive summary (maximum 2 sides A4) To date, most research on feather-pecking has involved either small-scale experimental trials, or observations of experimental flocks housed in research establishments. The aim of our study was to take an observational approach to identify and quantify management and disease associations with feather-pecking and vent pecking in adult laying birds in commercial alternative systems in the United Kingdom. The methods we employed were: A cross sectional study using a postal questionnaire on 200 alternative system egg producers to identify possible risks for feather (FP) and vent pecking (VP) and to generate hypotheses for further study. A case control study to refine these risk factors and test them in a more rigorous setting. One hundred flocks, 50 with feather pecking, 50 without, and matched on age were visited. -

RARE POULTRY CLASSES 8 Malay Pullet

ASIAN HARDFEATHER 36 Ko Shamo Black/White/Self Pullet Regional Show 37 Ko Shamo AOC Male Sec: Z Shakeshaft Tel: 07866 575316 38 Ko Shamo AOC Female Judges : Mr R Francis (Large Fowl) 39 Ko Shamo AOC Stag & Mr P Cox ( Bantams) 40 Ko Shamo AOC Pullet 0 41 Asil Male LARGE FOWL 42 Asil Female 43 Tuzo Male 1 Asil Male 44 Tuzo Female 2 Asil Female 45 Non Standard/AOV Male 3 Asil Stag 46 Non Standard/AOV Female 4 Asil Pullet See Juvenile section for entries 5 Malay Male 6 Malay Female 7 Malay Stag RARE POULTRY CLASSES 8 Malay Pullet 9 O Shamo Male (8.8lbs+) RARE POULTRY SOCIETY 10 O Shamo Female (6.6lbs+) Club Show 11 Chu Shamo Male (Under 8.8lbs) Sec: P M Fieldhouse Tel: 01934 12 Chu Shamo Female (under 6.6lbs) 824213 (eve) 13 Shamo Stag (Any size) Judges: Mr J Lockwood 14 Shamo Pullet (Any Size) (Hardfeather & Soft Feather Heavy) 15 Kulang Male Mr P Hayford (True Bantams, 16 Kulang Female Longtails, Juveniles, Pairs & Trios) 17 Satsumadori Male Mr A Hillary (Soft Feather Light 18 Satsumadori Female Breeds 1) 19 Yamato Gunkei Male Mr J Robertson (Soft Feather Light 20 Yamato Gunkei Female Breeds 2) 21 Yamato Gunkei Stag 22 Yamato Gunkei Pullet LONG TAILED LARGE 23 Non Standard/AOV Male 24 Non Standard/AOV Female 47 Yokohama Male See Juvenile section for entries 48 Sumatra Male 49 Yokohama Female BANTAMS 50 Sumatra Female 25 Malay Male LARGE SOFTFEATHER LIGHT 26 Malay Female BREEDS 27 Ko Shamo Black Red Male 28 Ko Shamo Black Red Stag 51 Andalusian Male 29 Ko Shamo Duckwing Male 52 Andalusian Female 30 Ko Shamo Duckwing Stag 53 Ayam Cemani M/F -

Poultry Talk the University of Arizona College of Agriculture Tucson, Arizona 85721 P’

Cooperative Exterisi S Poultry Talk The University of Arizona College of Agriculture Tucson, Arizona 85721 P’ Kenneth Olson, Extension Specialist, 4.H You won’t be around poultry breeders long before you will hear some strange sounding terms and you’ll be wondering what they mean. Poultry people like all groups have terms they understand, that are useful as they discuss their specialty with each other. As a newcomer to poultry either as a business or a hobby it is important that you learn these terms so that yoU too can take part in “Poultry Talk.” Here are some of the terms, listed in alphabetical order, for your convenience in looking up a term you may hear and not understand. ABDOMEN — The underpart of the body from the general weight, and often a variety of colors andlor breast to the tall. combs. A.B.A. — The initials of an organization devoted to the BRONZE — The metallic colored cast sometimes promotion of miniature sized poultry. (American found in plumage of black varieties. Bantam Association) BUTTERCUP COMB — A comb consisting of a single A.O.C. — The initials used to designate the remainder leader from the base of the beak to a hollow crown of the colors after listing several specific colors. set firmly on the center of the head surrounded by a (Any other color) circle of regular points. A.O.V. — The initials used to designate the remainder CAPE — The short feathers at the juncture of the back of ‘iarleties after listing some of the varieties in a and neck underneath the hackle and between the breed.