Indiana Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Revision Commission

Sen.R. Michael Young Sen. James Tomes Sen. James Arnold Sen. Greg Taylor Rep. Greg Steuerwald Rep. Thomas Washburne Rep. Charles Moseley Rep. Cherrish Pryor Gary Miller • Gretchen Gutman Mike McMahon Hon.Ma~retG.Robb CODE REVISION COMMISSION Jerry Bonnet Matt Light Legislative Services Agency 200 West Washington Street, Suite 301 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2789 Tel: (317) 233-0696 Fax: (317) 232-2554 John Stief(, Attorney for the Commission Authority: IC 2-5-1.1-10 MEETING MINUTES1 Meeting Date: October 15, 2013 Meeting Time: 1:30 P.M. Meeting Place: State House, 200 W. Washington St., Room 233 Meeting City: Indianapolis, Indiana· Meeting Number: 2 Members Present: Sen. R. Michael Young; Sen. James Tomes; Rep. Greg Steuerwald; Rep. Thomas Washburne; Rep. Charles Moseley; Rep. Cherrish Pryor; Gretchen Gutman; Mike McMahon; Hon. John G. Baker; Jerry Bonnet; Matt Light. Members Absent: Sen. James Arnold; Sen. Greg Taylor; Gary Miller. Staff Present: Mr. John Stieff, Director, Office of Code Revision, Legislative Services Agency; Mr. Craig Mortell, Attorney, Office of Bill Drafting and Research; Mr. John Kline, Attorney, Office of Code Revision; Ms. Stephanie Lawyer, Attorney, Office of Code Revision. 1 These minutes, exhibits, and other materials referenced in the minutes can be viewed electronically at http://www.in.gov/legislative Hard copies can be obtained in the Legislative Information Center in Room 230 ofthe State House in Indianapolis, Indiana. Requests for hard copies may be mailed to the Legislative Information Center, Legislative Services Agency, West Washington Street, Indianapolis, IN 46204-2789. A fee of$0.15 per page and mailing costs will be charged for hard copies. -

State-By-State Report on Authentication of Online Legal Resources

2009-10 UPDATES TO THE STATE-BY-STATE REPORT ON AUTHENTICATION OF ONLINE LEGAL RESOURCES AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF LAW LIBRARIES ELECTRONIC LEGAL INFORMATION ACCESS & CITATION COMMITTEE February 2010 Editor Tina S. Ching, Seattle University School of Law Authors Steven Anderson, Maryland State Law Library (Maryland) John R. Barden, Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library (Maine) Cathryn Bowie, State of Oregon Law Library (Oregon) Anne Burnett, Alexander Campbell King Law Library, University of Georgia School of Law (Georgia) A. Hays Butler, Rutgers Law School – Camden (New Jersey and Pennsylvania) Kathy Carlson, Wyoming State Law Library (Wyoming) Timothy L. Coggins, 2009-2010 Vice-Chair of the Electronic Legal Information Access and Citation Committee University of Richmond School of Law Library (Alabama, Arkansas and Vermont) Jane Colwin, Wisconsin State Law Library (Wisconsin) Terrye Conroy, Coleman Karesh Law Library University of South Carolina School of Law (South Carolina) Daniel Cordova, Colorado Supreme Court Library (Colorado) Jane Edwards, Michigan State University College of Law, and Ruth S. Stevens, Grand Valley State University (Michigan) Cynthia L. Ernst, Leon E. Bloch Law Library, University of Missouri – Kansas City (Missouri) Robert M. Ey, WolfBlock, LLP (Massachusetts) Janet Fisher and Tony Bucci, Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records (Arizona) Jenny R.F. Fujinaka, Hawai‘i Supreme Court Law Library (Hawaii) STATE-BY-STATE REPORT ON AUTHENTICATION OF ONLINE LEGAL RESOURCES 2009-10 UPDATE AUTHORS Barbara L. Golden, Minnesota State Law Library (Minnesota) Michael Greenlee, University of Idaho Law Library (Idaho) Kathleen Harrington, Nevada Supreme Court Library (Nevada) Stephanie P. Hess, Nova Southeastern Law School (Florida) Sarah G. -

City of Elwood, Indiana Code of Ordinances

CITY OF ELWOOD, INDIANA CODE OF ORDINANCES Contains 2018 S-9 Supplement, current through: Ordinance 2308, passed 8-6-18 and 2018 Advance Legislative Service Pamphlet No. 5 Published by: AMERICAN LEGAL PUBLISHING CORPORATION One West Fourth Street h 3rd Floor h Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 1-800-445-5588 h www.amlegal.com ELWOOD, INDIANA CODE OF ORDINANCES TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter TITLE I: GENERAL PROVISIONS 10. General Provisions TITLE III: ADMINISTRATION 30. Governmental Organization 31. City Officials 32. Common Council 33. Authorities, Boards, Commissions and Departments 34. City Court 35. Finance, Taxation and Funds 36. Personnel 37. City Policies TITLE V: PUBLIC WORKS 50. Garbage 51. Water 52. Sewers 53. Industrial Waste TITLE VII: TRAFFIC CODE 70. General Regulations 71. Traffic Rules 72. Parking 73. Recreational Vehicles 74. Traffic Schedules 75. Parking Schedules 76. Alternative Transportation 2009 S-5 1 2 Elwood - Table of Contents TITLE IX: GENERAL REGULATIONS 90. Abandoned Vehicles 91. Animals 92. Fair Housing 93. Fire Regulations 94. Nuisances 95. Parks 96. Streets and Sidewalks TITLE XI: BUSINESS REGULATIONS 110. Sexually Oriented Businesses 111. Amusements 112. Cable Television 113. Residential Sales 114. Peddlers, Itinerant Merchants, and Solicitors TITLE XIII: GENERAL OFFENSES 130. General Offenses TITLE XV: LAND USAGE 150. Building Regulations 151. Flood Hazard Prevention 152. Subdivisions 153. Zoning 154. Historic Buildings 155. Rental Registration Program 156. Abandoned Structure Monitoring Program TABLE OF SPECIAL ORDINANCES Table I. Franchise Agreements II. Street Closings 2018 S-9 Table of Contents 3 PARALLEL REFERENCES References to Indiana Code References to 1966 Code References to Ordinances INDEX 4 Elwood - Table of Contents PARALLEL REFERENCES References to Indiana Code References to 1966 Code References to Ordinances 1 2 Elwood - Parallel References REFERENCES TO INDIANA CODE I.C. -

The Laws of Indiana and Wisconsin

Chapter 7 Researching outside of Illinois: The Laws of Indiana and Wisconsin Heidi Frostestad Kuehl Foreign, Comparative, and International Law Librarian and Coordinator of Educational Programming and Outreach Pritzker Legal Research Center Northwestern University School of Law Beginning State-Specific Legal Research in Indiana or Wisconsin The first step of any type of legal research is finding background materials and sources for jurisdictional legal research. Legal researchers rely upon secondary sources, such as legal encyclopedias, American Law Reports, treatises, nutshells, or other types of books about legal topics, to begin their research in topics of the law or particular jurisdictions of law. Like with topical research or Federal research, it is wise to begin State law research with a legal encyclopedia (if the State has one) to decipher the terminology of particular State law research topics and collect citations to primary law that are found in the footnotes of a secondary source. For a national scope and treatment of States, researchers may choose to consult one or both of the two prominent legal encyclopedias: American Jurisprudence 2d (Am.Jur.2d) or Corpus Juris Secundum (C.J.S.). Both of these national legal encyclopedias are available in print in most academic law libraries or court libraries or are also available online on Westlaw/WestlawNext. In addition to national legal encyclopedias, there are also State-specific legal encyclopedias that provide great overviews and analysis for State-specific legal topics. For the laws of Indiana, researchers rely on West’s Indiana Law Encyclopedia to begin topical areas of legal research. In Wisconsin, legal researchers begin their research in other types of secondary sources, such as the Wisconsin Practice series or one of the national legal encyclopedias (Am.Jur.2d or C.J.S.), because there is not a State-specific legal encyclopedia. -

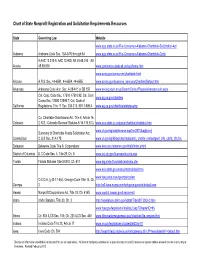

Chart of State Nonprofit Registration and Solicitation Requirements Resources

Chart of State Nonprofit Registration and Solicitation Requirements Resources State Governing Law Website www.ago.state.al.us/File-Consumer-Alabama-Charitable-Solicitation-Act Alabama Alabama Code Sec. 13A-9-70 through 84 www.ago.state.al.us/File-Consumer-Alabama-Charitable-Code 9 AAC 12.010-9. AAC 12.900; AS 45.68.010 - AS Alaska 45.68.900 www.commerce.state.ak.us/occ/home.htm www.azag.gov/consumer/charitable.html Arizona A.R.S. Sec. 44-6551, 44-6554, 44-6555 www.azsos.gov/business_services/Charities/Default.htm Arkansas Arkansas Code Ann. Sec. 4-28-401 or SB 156 www.arkleg.state.ar.us/SearchCenter/Pages/arkansascode.aspx Cal. Corp. Code Sec. 17510-17510.95; Cal. Govt www.ag.ca.gov/charities Codes Sec. 12580-12599.7; Cal. Code of California Regulations, Title 11 Sec. 300-310, 991.1-999.4 www.ag.ca.gov/charities/statutes.php Co. Charitable Solicitations Act, Title 6, Article 16, Colorado C.R.S.; Colorado Revised Statutes 6-16-110.5(3), www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/charities/charitable.htm www.ct.gov/ag/cwp/browse.asp?a=2074&agNav=| Summary of Charitable Funds Solicitation Act; Connecticut C.G.S Sec. 21A-175 www.ct.gov/ag/lib/ag/charities/public_charity_revisedgenl_info_cscfa_(2).doc Delaware Delaware Code Title 8: Corporations www.delcode.delaware.gov/title8/index.shtml District of Columbia D.C.Code Sec. 5, Title 29, Ch. 8 www.brc.dc.gov/licenses/dccode.asp Florida Florida Statutes Title XXXVI, Ch. 617 www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm www.sos.state.ga.us/securities/default.htm www.law.justia.com/georgia/codes/ O.C.G.A. -

INDIANA LAW UPDATE by Ronald J. Waicukauski and Brad A. Catlin ISSUE 2: 2017 SERIES – March 30, 2017 Available Online At

INDIANA LAW UPDATE by Ronald J. Waicukauski and Brad A. Catlin ISSUE 2: 2017 SERIES – March 30, 2017 Available online at: www.IndianaLawUpdate.com 301 Massachusetts Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 T: 317-633-8787 [email protected] [email protected] IN THE NEWS: Legal advertising blows past $1 billion and goes viral .................... 2 1. The Governor and Public Records; Groth v. Pence, 67 N.E.3d 1104 (Ind. Ct. App. 1/9/17) (Najam) .............................................................................................. 3 2. Personal Jurisdiction of BMV Depends on Service on Attorney General; Indiana Bureau of Motor Vehicles v. Watson, 70 N.E.3d 380 (Ind. Ct. App. 1/23/17) (Robb) ....................................................................................................... 5 3. 180-Day Extension for Med Mal Claims Strictly Applied; Dermatology Associates, P.C. v. White, 67 N.E.3d 1173 (Ind. Ct. App. 1/19/17) (Robb) ........... 6 4. No Constructive Fraud Without Concealment; Central Indiana Podiatry, P.C. v. Barnes & Thornburg, LLP, 2017 WL 819741 (Ind. Ct. App. 11/16/16) (May) . 9 5. A Voidable Error Will Not Satisfy Tr. R. 60(B)(6) Requirements for Relief from Judgment; Koonce v. Finney, 68 N.E.3d 1086 (Ind. Ct. App. 1/13/17 (May) ..... 11 6. Failing To Follow Proper Rule 60(B) Procedure Results In Dismissal Of Motion; Falatovics v. Falatovics, 2017 WL 943970 (Ind. Ct. App. 3/10/17) (Crone) .................................................................................................................. 13 7. Law Firms Must Comply With Credit Services Organizations Act; Consumer Attorney Services, P.A. v. State of Indiana, 2017 WL 1057413 (Ind. 3/21/17) (Massa) ................................................................................................................. 15 8. Person Who May Have Exerted Undue Influence Always Has The Burden Of Proof; Garrison v. -

Survey of Federal & State Laws

Survey of Federal & State Laws: Understanding Your Right To Be Treated Fairly and Without Discriminaon in Restaurants, Stores, and Other Businesses PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION LAWS BASED ON RACE, COLOR, AND/OR NATIONAL ORIGIN Last Updated : September 20, 2020 ** This survey is provided solely for informaonal purposes. Stop AAPI Hate does not warrant the accuracy of the informaon contained herein. Users are encouraged to seek advice from a licensed aorney regarding potenal violaons of any applicable public accommodaon laws. ** CAVEATS (1) This survey reviews general public accommodaon statutes under federal law and the laws of the states and District of Columbia. A review of case law interpreng the scope and applicaon of these statutes as well as a review of other statutes that may provide general an-discriminaon protecons or other indirect legal protecons are beyond the scope of this survey. (2) The scope of public accommodaon statutes differ from jurisdicon to jurisdicon based on differences in how key terms are statutorily defined and the existence of different statutory exempons to the statutes. (3) Addional public accommodaon laws may exist at the local (sub-federal/state) level. A comprehensive survey of which localies have enacted such laws is beyond the scope of this survey. However, in jurisdicons where no statewide public accommodaon laws for individuals based on race, color, or naonal origin exist, an aempt has been made to determine whether local public accommodaon laws exist in major urban centers in those jurisdicons. 1 (4) To the extent this survey indicates no private right of acon exists, that merely indicates no private right of acon is expressly authorized by that jurisdicon’s general public accommodaon statute. -

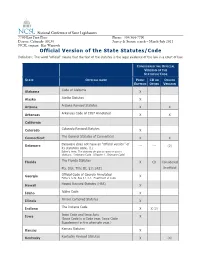

Official Version of the State Statutes/Code Definition: the Word "Official" Means That the Text of the Statutes Is the Legal Evidence of the Law in a Court of Law

National Conference of State Legislatures 7700 East First Place Phone: 303/364-7700 Denver, Colorado 80230 Survey & Statute search – March-July 2011 NCSL contact: Kae Warnock Official Version of the State Statutes/Code Definition: The word "official" means that the text of the statutes is the legal evidence of the law in a court of law. CONSIDERED THE OFFICIAL VERSION OF THE STATUTES/CODE STATE OFFICIAL NAME PRINT CD OR ONLINE EDITION OTHER VERSION Alabama Code of Alabama X Alaska Alaska Statutes X Arizona Arizona Revised Statutes X X Arkansas Arkansas Code of 1987 Annotated X X California Colorado Colorado Revised Statutes X Connecticut The General Statutes of Connecticut X X Delaware Delaware does not have an “official version” of --- --- (2) its statutory code. (1) Editor’s note: The statutes do give a name to use in citations. Delaware Code (Chapter 1. Delaware Code) Florida The Florida Statutes X CD Considered Fla. Stat. Title III, §11.2421 Unofficial Georgia Official Code of Georgia Annotated X Editor’s note: See § 1-1-1. Enactment of Code Hawaii Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS) X Idaho Idaho Code X Illinois Illinois Compiled Statutes X Indiana The Indiana Code X X (3) Iowa Iowa Code and Iowa Acts X (Iowa Code in a Code year. Iowa Code Supplement in the alternate year.) Kansas Kansas Statutes X Kentucky Kentucky Revised Statutes X (4) CONSIDERED THE OFFICIAL VERSION OF THE STATUTES/CODE STATE OFFICIAL NAME PRINT CD OR ONLINE EDITION OTHER VERSION Louisiana West's Louisiana Statutes Annotated X Editor’s note: See RS 1:1 §1. -

State of Indiana ) in the Marion Superior Court ) County of Marion ) Cause No

49D02-2104-PL-014586 Filed: 4/30/2021 3:06 PM Clerk Marion Superior Court 2 Marion County, Indiana STATE OF INDIANA ) IN THE MARION SUPERIOR COURT ) COUNTY OF MARION ) CAUSE NO. JOHN R. WHITAKER, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, as established ) by Indiana Code section 2-5-1.1-1, RODRIC ) BRAY in his official capacity as the President Pro ) Tempore of the Indiana State Senate and a member ) of the Indiana Legislative Council, TODD ) HUSTON, in his official capacity as the Speaker of ) the Indiana State House of Representatives and a ) member of the Indiana Legislative Council, and ) THE INDIANA GENERAL ASSEMBLY, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF The Plaintiff, John R. Whitaker (“Citizen”), by counsel, and for his request for declaratory and injunctive relief against the Defendants the Indiana Legislative Council as established by Indiana Code section 2-5-1.1-1, Rodric Bray, in his official capacity as the President Pro Tempore of the Indiana State Senate and a member of the Legislative Council, Todd Huston, in his official capacity as the Speaker of the Indiana State House of Representatives and a member of the Legislative Council, and the Indiana General Assembly (collectively, the “Defendants”) states the following: INTRODUCTION 1. This case seeks to put a stop to the Indiana General Assembly’s (“General Assembly”) unconstitutional attempt to grant itself the power to call a special session of its body, a function exclusively given to the Governor of the state of Indiana (“Governor”) under the Indiana Constitution. 2. The backdrop to this case is the historic public health crisis that Indiana, along with the rest of the world, has been waging against the coronavirus disease 2019 (“COVID-19”), which has been the single gravest public health threat in over a century. -

States with Laws Or Codes to Protect Police Service Dogs from Assault, Battery Or Death

States with Laws or Codes to Protect Police Service Dogs from Assault, Battery or Death By Terry Fleck States with Laws or Codes: There are forty-nine (49) states that have laws or codes to protect police service dogs from assault, battery or death. Here is a listing of those states in alphabetical order and their law: STATES: Alabama: Code of Alabama Section 13A-11-15 Alaska: Alaska Statute Sections 11.56.705, 11.56.710, 11.56.715, 11.81.900 Arizona: Arizona Revised Statute Section 13-2910 Arkansas: Arkansas Code Section 5-54-126 California: California Penal Code Section 600 Colorado: Colorado Revised Statute Sections 18-1.3-602, 18-9-202 Connecticut: Connecticut General Statute Sections 53-247, 53a-3, 5-249 Delaware: Delaware Code Title 11, Section 1250 Florida: Florida Statute: 843.19 Georgia: Official Code of Georgia Section 16-11-107 Hawaii: Hawaii Revised Statue Section 711-1109.4, 711-1109.5 Idaho: Idaho Code Section 18-7039 Illinois: 510 Illinois Compiled Statutes (ILCS) Sections 70/2.08, 70/4.03, 70/4.04 Indiana: Indiana Code Sections 35-46-3-11, 35-46-3-11.3 Iowa: Iowa Code Section 717B.9 Kansas: Kansas Statute Section 21-4318 Kentucky: Kentucky Penal Code, (Kentucky Revised Statue) KRS Sections 525.010, 525.200, 525.205, 525.210, 525.215, 525.220 Louisiana: Louisiana Revised Statute Section 14:102.8 Maine: Maine Revised Statute 17 Section 752-B Maryland: Maryland Criminal Law Code Section 10-606 Massachusetts: Laws of Massachusetts Chapter 272 Section 77A Michigan: Michigan Penal Code Section 750.50c Minnesota: Minnesota Statute -

2020 Interim Study Committee on Corrections and Criminal Code: CONSENT

2020 Interim Study Committee on Corrections and Criminal Code: CONSENT 9245 N. Meridian Street, Suite 227 Indianapolis, IN 46260 317.624.2370 icesaht.org It’s Simple “It’s time to recognize that physically penetrating another person’s body without their permission is serious misconduct that our society and our criminal law ought to condemn. The need for permission is elementary, and it need not be understood in terms of written contracts, artificial verbal formulas, or any other unrealistic behavioral ritual. Ordinary citizens know what it means to have permission, expressed or implied, and they know that it is unacceptable to take liberties with someone’s person or property without permission. That’s all that consent means, and it’s a matter of simple justice to require it.” – Stephen J. Schulhofer icesaht.org STATES WITH CONSENT LEGISLATION State Statute Definition All of these states have a definition requiring “freely given consent” or “affirmative consent” Illinois 720 ILCS 5/11-1.70. “Consent” means a freely given agreement to the act of sexual penetration or People v. Roldan, sexual conduct in question. Lack of verbal or physical resistance or submission 2015 IL App (1st) by the victim resulting from the use of force or threat of force by the accused 131962, ¶ 19. shall not constitute consent. The manner of dress of the victim at the time of the offense shall not constitute consent. A person who initially consents to sexual penetration or sexual conduct is not deemed to have consented to any sexual penetration or sexual conduct that occurs after he or she withdraws consent during the course of that sexual penetration or sexual conduct. -

Banking, Business, and Contract Law

BANKING, BUSINESS, AND CONTRACT LAW FRANK SULLIVAN, JR.*,** This Article describes in some detail an important statute enacted by the 2017 session of the Indiana General Assembly and surveys banking, business, and contract law decisions made by the Indiana Supreme Court and Indiana Court of Appeals between September 1, 2016, and August 31, 2017. This Article includes discussion of many so-called not-for-publication “memorandum” decisions of the court of appeals because such decisions often establish new law; clarify, modify, or criticize existing law; or involve legal or factual issues of unique interest or substantial public importance. Whatever the appellate rules are at the moment about the citation of memorandum decisions, they contain critical guidance on Indiana law and cannot be ignored.1 This Article will itemize neither every statutory change nor every such appellate case involving banking, business, and contract law decided during the survey period. Instead, it will highlight the big-picture issues in these fields as well as some practice pointers for both transactions lawyers and litigators. I. BUSINESS ENTITY STATUTE HARMONIZATION On April 21, Governor Eric Holcomb signed into law an enactment of the General Assembly2 that Secretary of State Connie Lawson called “the most far- reaching revision of Indiana business laws in more than two decades.”3 The new act consolidates in a single place in the Indiana Code and harmonizes certain administrative provisions and provisions governing transactions that had * Professor of Practice, Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. Justice, Indiana Supreme Court (1993-2012). LL.M., University of Virginia School of Law (2001); J.D., Indiana University Maurer School of Law (1982); A.B., Dartmouth College (1972).