Almost a Century of Central Bank Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

42Nd Annual Report of the Bank for International Settlements

BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS FORTY-SECOND ANNUAL REPORT 1st APRIL 1971 - 31st MARCH 1972 BASLE 12th June 1972 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction i I. The Crisis of the Dollar and the Monetary System 3 The US balance of payments (p. ß) ; US measures to limit the deficit (p. 11) ; the balance of surpluses and deficits (p. iß); the growing disequilibrium of the system (p. 16); prelude to 15 th August 1971 (p. 2ß); floating exchange rates (p. 27); the Smithsonian agreement (p. 29); post-Smithsonian developments (p. ßo) II. Survey of Economic and Monetary Developments and Policies 34 The domestic economic scene (p. ß4); money, credit and capital markets (p. ß8); developments and policies in individual countries: United States (p. 4;), Canada (p. 49), Japan (p. JI), United Kingdom (p. jß), Germany (p. JJ), France (p. 60), Italy (p. 6ß), Belgium (p. 6j), Netherlands (p. 66), Switzerland (p. 68), Austria (p. 69), Denmark (p. 70), Norway (p. 71), Sweden (p. 72), Finland (p. 74), Spain (p. 7j), Portugal (p. 76), Yugo- slavia (p. 77), Australia (p. 78), South Africa (p. 79); eastern Europe: Soviet Union (p. 80), German Democratic Republic (p. 80), Poland (p. 80), Chechoslovakia (p. 81), Hungary (p. 81), Rumania (p. 82), Bulgaria (p. 82) III. World Trade and Payments 83 International trade (p. 8ß); balances of payments (p. 8j): United States (p. 87), Canada (p. 89), Japan (p. 91), United Kingdom (p. 9ß), Germany (p. 94), France (p. 96), Italy (p. 98), Belgium-Luxemburg Economic Union (p. 100), Netherlands (p. ioi), Switzerland (p. 102), Austria (p. -

History of Federal Reserve Free Edition

Free Digital Edition A Visual History of the Federal Reserve System 1914 - 2009 This is a free digital edition of a chart created by John Paul Koning. It has been designed to be ap- chase. Alternatively, if you have found this chart useful but don’t want to buy a paper edition, con- preciated on paper as a 24x36 inch display. If you enjoy this chart please consider buying the paper sider donating to me at www.financialgraphart.com/donate. It took me many months to compile the version at www.financialgraphart.com. Buyers of the chart will recieve a bonus chart “reimagin- data and design it, any support would be much appreciated. ing” the history of the Fed’s balance sheet. The updated 2010 edition is also now available for pur- John Paul Koning, 2010 FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE, the Federal Reserve has Multiple data series including the Fed’s balance sheet, This image is published under a Creative Commons been governing the monetary system of the United States interest rates and spreads, reserve requirements, chairmen, How to read this chart: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 License since 1914. This chart maps the rise of the Fed from its inflation, recessions, and more help chronicle this rise. While Start origins as a relatively minor institution, often controlled by this chart can only tell part of the complex story of the Fed, 1914-1936 Willliam P. Harding $16 Presidents and the United States Department of the we trust it will be a valuable reference tool to anyone Member, Federal Reserve Board 13b Treasury, into an independent and powerful body that rivals curious about the evolution of this very influential yet Adviser to the Cuban government Benjamin Strong Jr. -

U.S. Policy in the Bretton Woods Era I

54 I Allan H. Meltzer Allan H. Meltzer is a professor of political economy and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University and is a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. This paper; the fifth annual Homer Jones Memorial Lecture, was delivered at Washington University in St. Louis on April 8, 1991. Jeffrey Liang provided assistance in preparing this paper The views expressed in this paper are those of Mr Meltzer and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System or the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. U.S. Policy in the Bretton Woods Era I T IS A SPECIAL PLEASURE for me to give world now rely on when they want to know the Homer Jones lecture before this distinguish- what has happened to monetary growth and ed audience, many of them Homer’s friends. the growth of other non-monetary aggregates. 1 am persuaded that the publication and wide I I first met Homer in 1964 when he invited me dissemination of these facts in the 1960s and to give a seminar at the Bank. At the time, I was 1970s did much more to get the monetarist case a visiting professor at the University of Chicago, accepted than we usually recognize. 1 don’t think I on leave from Carnegie-Mellon. Karl Brunner Homer was surprised at that outcome. He be- and I had just completed a study of the Federal lieved in the power of ideas, but he believed Reserve’s monetary policy operations for Con- that ideas were made powerful by their cor- gressman Patman’s House Banking Committee. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

The European Currency Snake

The European currency snake Source: CVCE. European NAvigator. Étienne Deschamps. Copyright: (c) CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/the_european_currency_snake-en-d4f8d8aa-a518- 4e56-9e19-957ea8d54542.html Last updated: 08/07/2016 1/2 The European currency snake Europe was seriously weakened by the currency turmoil in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The combined effect of the devaluation of the French franc, the upward revaluation of the German mark and the collapse of the Bretton Woods International Monetary System destabilised European markets. Furthermore, exchange rates between the currencies of the Member States had to be fixed before a common market could be created. The German Minister for Finance and Economic Affairs, Karl Schiller, advocated a rigorous stability policy in order to resolve the crisis. France hesitated at first but then came round to supporting the German idea of attaining monetary stability. The Smithsonian Agreement, signed in Washington on 18 December 1971, set new parities between European currencies and the dollar. It also introduced what was known as the currency tunnel, which extended the exchange rate fluctuation margins of the main European currencies to 2.25 % around a central rate. Meeting in Basle on 10 April 1972, the Committee of Governors of the European central banks introduced an additional mechanism to narrow exchange rate fluctuation. -

Macroeconomic Policy

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: International Economic Cooperation Volume Author/Editor: Martin Feldstein, ed. Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-24076-2 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/feld88-4 Publication Date: 1988 Chapter Title: Macroeconomic Policy Chapter Author: Stanley Fischer, W. Michael Blumenthal, Charles L. Schultze, Alan Greenspan, Helmut Schmidt Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c9786 Chapter pages in book: (p. 11 - 78) Macroeconomic 1 Policy 1. Stanley Fischer 2. W. Michael Blumenthal 3. Charles L. Schultze 4. Alan Greenspan 5. Helmut Schmidt 1. Stanley Fischer International Macroeconomic Policy Coordination International cooperation in macroeconomic policy-making takes place in a multitude of settings, including regular diplomatic contacts, the IMF, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the Eu ropean Monetary System (EMS), the OECD, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), and summits. It takes a multitude of forms, from sharing information about current and future policies, through consul tation about decisions, to actual coordination of policies. Coordination "implies a significant modification of national policies in recognition of international economic interdependence." 1 Coordination holds out the promise of mutual gains resulting from the effects of economic policy decisions in one country on the econ omies of others. The Bonn Summit of 1978, in which Germany agreed to an expansionary fiscal policy in exchange for a U.S. commitment to raise the price of oil to the world level, is a much quoted example of policy coordination. 2 That agreement, followed by the second oil shock and increased inflation, was later viewed by many as a mistake. -

The Decline of Sterling Managing the Retreat of an International Currency, 1945-1992

The Decline of Sterling Managing the Retreat of an International Currency, 1945-1992 Catherine R. Schenk CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Contents List of figures { page x List of tables xiii Acknowledgements xv 1 Introduction 1 Evolution of the international monetary system 7 Britain in the world economy 13 Measuring sterling's international role 21 Summary and outline of the book 27 Part I Reconstructing the International Monetary System 1945-1959 35 2 The post-war international monetary system 1945-1950 37 The post-war settlement 37 The 1947 convertibility crisis 60 Devaluation, .1949 68 Conclusions 80 3 The return to convertibility 1950-1959 83 Sterling as a reserve currency 83 Sterling as a trading currency 95 The sterling exchange rate 100 Convertibility on the current account 102 Conclusions 115 Part II Accelerating the Retreat: Sterling in the 1960s 117 4 Sterling and European integration 119 Erosion of traditional relationships in the 1960s 121 The first application, 1961-1963 124 The second application, 1967 131 The final battle for accession, 1970-1972 - 138 Conclusions 151 Contents The 1967 sterling devaluation: relations with the United States and the IMF 1964-1969 155 Devaluation and Anglo-American relations 157 Devaluation and the IMF 185 Conclusions 204 Sterling and the City 206 Measuring sterling as a commercial currency 208 Sterling in banking and finance 212 Capital controls on sterling 215 The eclipse of sterling, 1958-1970 224 Conclusions 238 Multilateral negotiations: sterling and the-reform of the international monetary -

Danmarks Nationalbank Working Papers 2004 • 12

DANMARKS NATIONALBANK WORKING PAPERS 2004 • 12 Kim Abildgren Danmarks Nationalbank A chronology of Denmark’s exchange-rate policy 1875-2003 April 2004 The Working Papers of Danmarks Nationalbank describe research and development, often still ongoing, as a contribution to the professional debate. The viewpoints and conclusions stated are the responsibility of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Danmarks Nationalbank. As a general rule, Working Papers are not translated, but are available in the original language used by the contributor. Danmarks Nationalbank's Working Papers are published in PDF format at www.nationalbanken.dk. A free electronic subscription is also available at this Web site. The subscriber receives an e-mail notification whenever a new Working Paper is published. Please direct any enquiries to Danmarks Nationalbank, Information Desk, Havnegade 5, DK-1093 Copenhagen K Denmark Tel.: +45 33 63 70 00 (direct) or +45 33 63 63 63 Fax : +45 33 63 71 03 E-mail:[email protected] Text may be copied from this publication provided that Danmarks Nationalbank is specifically stated as the source. Changes to or misrepresentation of the content are not permitted. Nationalbankens Working Papers beskriver forsknings- og udviklingsarbejde, ofte af foreløbig karakter, med henblik på at bidrage til en faglig debat. Synspunkter og konklusioner står for forfatternes regning og er derfor ikke nødvendigvis udtryk for Nationalbankens holdninger. Working Papers vil som regel ikke blive oversat, men vil kun foreligge på det sprog, forfatterne har brugt. Danmarks Nationalbanks Working Papers er tilgængelige på Internettet www.nationalbanken.dk i pdf- format. På webstedet er det muligt at oprette et gratis elektronisk abonnement, der leverer en e-mail notifikation ved enhver udgivelse af et Working Paper. -

From Bretton Woods to Brussels: a Legal Analysis of the Exchange-Rate Arrangements of the International Monetary Fund and the European Community

Fordham Law Review Volume 62 Issue 7 Article 9 1994 From Bretton Woods to Brussels: A Legal Analysis of the Exchange-Rate Arrangements of the International Monetary Fund and the European Community Richard Myrus Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard Myrus, From Bretton Woods to Brussels: A Legal Analysis of the Exchange-Rate Arrangements of the International Monetary Fund and the European Community, 62 Fordham L. Rev. 2095 (1994). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol62/iss7/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM BRETTON WOODS TO BRUSSELS: A LEGAL ANALYSIS OF THE EXCHANGE-RATE ARRANGEMENTS OF THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND AND THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY RICHARD MYR US INTRODUCTION Exchange rates represent the price at which the currency of one coun- try can be purchased with the currency of another.t These rates indi- rectly affect the costs of the goods, capital, and services that flow across national borders.2 According to Joseph Gold, former General Counsel of the International Monetary Fund, "[fqor most countries, there is no single price which has such an important influence on both the financial world-in terms of asset values and rates of return, and on the real world-in terms of production, trade and employment. -

Interview with Edwin M. Truman Former Staff Director, Division of International Finance

Federal Reserve Board Oral History Project Interview with Edwin M. Truman Former Staff Director, Division of International Finance Date: November 30, 2009, and December 22, 2009 Location: Washington, D.C. Interviewers: David H. Small, Karen Johnson, Larry Promisel, and Jaime Marquez Federal Reserve Board Oral History Project In connection with the centennial anniversary of the Federal Reserve in 2013, the Board undertook an oral history project to collect personal recollections of a range of former Governors and senior staff members, including their background and education before working at the Board; important economic, monetary policy, and regulatory developments during their careers; and impressions of the institution’s culture. Following the interview, each participant was given the opportunity to edit and revise the transcript. In some cases, the Board staff also removed confidential FOMC and Board material in accordance with records retention and disposition schedules covering FOMC and Board records that were approved by the National Archives and Records Administration. Note that the views of the participants and interviewers are their own and are not in any way approved or endorsed by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Because the conversations are based on personal recollections, they may include misstatements and errors. ii Contents November 30, 2009, Morning (Part 1 of 3 of the Interview) ..................................................... 1 General Background and Experience at Yale University ............................................................... 1 Joining the Federal Reserve Board Staff ...................................................................................... 23 Early Years in the Division of International Finance and Forecasting ................................... 25 November 30, 2009, Afternoon (Part 2 of 3 of the Interview) ................................................. 49 Early Projects and Reforming the International Monetary System ......................................... -

Download (Pdf)

For release on delivery Statement by Arthur F. Burns Chairman, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System before the Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs United States Senate February 24, 1972 The Board of Governors at the Federal Reserve System strongly supports enactment of the Par Value Modification Act. Prompt passage of this bill will fulfill an important commitment undertaken by the United States as part of the Smithsonian Agree- ment reached by the Group of Ten countries on December 18, 1971. The Par Value Modification Act The Par Value Modification Act proposes a new par value for the dollar in the International Monetary Fund. We will thus have a new official dollar price of gold: an ounce of gold will in the future be carried on the books at $38 instead of $35 as at present. The Act does not deal with the issue of convertibility, and therefore does not affect the present suspension of convertibility of dollars into gold or other international reserve assets. The proposed change in the par value of the dollar will have several financial and accounting consequences. First, the value of the Treasury's gold and other reserve assets will be written up by 8« 57 per cent, or about a billion dollars. Second, the Treasury will be able to issue new gold certificates to the Federal Reserve Banks for this amount, and its cash balance will rise to the extent that it does so. Third, the dollar value of subscriptions and contributions to several international financial organizations will need to be increased* -2- The net result of the various financial and accounting adjustments, as the Secretary of the Treasury has informed this Committee in detail, will somewhat improve the Treasury's cash position and leave both budgetary expenditures and the overall dollar assets and liabilities of the U.S. -

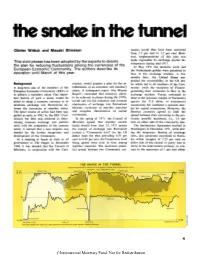

The Snake in the Tunnel

the snake in the tunnel Giinter Wittich and Masaki Shiratori rencies would thus have been narrowed from 1.5 per cent to 1.2 per cent. Ho- ever, implementation of this plan was made impossible by exchange market de- This vivid phrase has been adopted by the experts to denote velopments during mid-1971. the plan for reducing fluctuations among the currencies of the In May 1971 the deutsche mark and European Economic Community. The authors describe its the Netherlands guilder were permitted to operation until March of this year. float in the exchange markets. A few months later, the United States sus- pended the convertibility of the US dol- Background mission, would prepare a plan for the es- lar which led to all members of the Com- A long-term aim of the members of the tablishment of an economic and monetary munity (with the exception of France) European Economic Community (EEC) is union. A subsequent report (the Werner permitting their currencies to float in the to achieve a monetary union. One impor- Report) concluded that monetary union, exchange markets. France continued to tant feature of such a union would be to be achieved in phases during the 1970s, observe the previous margin of fluctuation either to adopt a common currency or to would call for the reduction and eventual against the U S dollar in commercial eliminate exchange rate fluctuations be- elimination of exchange rate fluctuations transactions but instituted a separate mar- tween the currencies of member states. between currencies of member countries ket for capital transactions. Moreover, the The latter course of action had been sug- and complete liberalization of capital Benelux countries agreed to limit the gested as early as 1962 by the EEC Com- movements.