The ORCA Foundation in Plettenberg Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds in Zoos in England: an Assessment of Welfare, Conservation and Education in 2013

Birds in Zoos in England: An Assessment of Welfare, Conservation and Education in 2013 Report by Craig Redmond Commissioned by the Captive Animals’ Protection Society This report has been researched and written by Craig Redmond on behalf of the Captive Animals’ Protection Society. Craig Redmond is an independent animal rights consultant who was previously CAPS’ Campaigns Director, having worked at the charity for over a decade. He has extensive knowledge of the zoo industry and has co- ordinated previous investigations and research projects into UK zoos. In addition, he has several years’ active involvement in programmes to protect migratory birds from illegal hunting across the Mediterranean. The Captive Animals’ Protection Society (CAPS) is a UK-based charity leading the campaign to end the use of animals in entertainment. Through a combination of undercover investigations, research, campaigns, political lobbying and education, CAPS aims to stop the exploitation of animals in entertainment, particularly in zoos, circuses and the exotic pet trade. The charity’s evidence-based campaigns and strong ethical basis ensure we can make a significant difference to the lives of animals in ending their exploitation. Working for a world without cages, CAPS encourages a more compassionate attitude and relationship between humans and other animals. The Captive Animals’ Protection Society is a registered charity and receives no government funding. Registered number: 1124436 We wish we could fly, We wish we could hear the tiniest of sounds And swoop gracefully and swiftly To the most definite of conclusions. The wind and wing’s secret is this; We do fly, We do hear the tiniest of sounds. -

2Nd Congress of the European Federation for Primatology

Abstracts Folia Primatol 2008;79:305–401 Published online: June 13, 2008 DOI: 10.1159/000137690 2nd Congress of the European Federation for Primatology Prague, September 3–7, 2007 Editors: Vaclav Vancata and Marina Vancatova, Prague, Czech Republic Do Capuchin Monkeys (Cebus apella) Deal with Tokens as They Do with Real Food? Elsa Addessia , Alessandra Mancini a, b , Lara Crescimbenea , b , Elisabetta Visalberghi a a Unit of Cognitive Primatology and Primate Centre, Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, CNR, Rome, b Università La Sapienza, Rome, Italy E-Mail: [email protected] Key Words: Transitivity ؒ Cebus apella ؒ T o k e n s Recent studies on the use of tokens (i.e., inherently non-valuable objects that acquire an associated value upon exchange for food with an experimenter) in non-human primates did not investigate whether individuals use tokens as symbols. Therefore, we evaluated this topic in capuchin monkeys. We trained 10 capuchins to associate two types of tokens (A and B) with different amounts of food. Then, we assessed performance in relative numerousness judgment tasks with food (Experiment 1) and with tokens A (Experiment 2). In both experiments, all ca- puchins chose the highest quantity regardless of the type of item presented. Then, in Experi- ment 3 one token B was presented against 1–5 tokens A. Four capuchins used a flexible strategy, maximizing their payoff. Experiment 4 required the capuchins to choose between 1 and 2 to- kens B, and 3 and 6 tokens A. Only one subject always maximized his payoff in this task. -

South Africa: Battlefields & Bodegas 18 March – 1 April 2020

SOUTH AFRICA: BATTLEFIELDS & BODEGAS 18 MARCH – 1 APRIL 2020 FROM £7,995 PER PERSON Tour Leader: Andrew Cumming DRAMATIC SCENERY AND EXHILARATING ADVENTURE South Africa is often described as ‘a world in one country’, and this tour combines four of her most enduring attractions: wildlife, battlefields, wine and culture. From the cosmopolitan city of Cape Town, to the rolling vineyards of the winelands, the spectacular coastal scenery and battlefields rich in history, South Africa needs little introduction. In the course of the tour we explore not only Cape Town itself, but also the beautiful Kirstenbosch National Botanical Gardens and the dramatic scenery of the Cape Point Nature Reserve. We then venture to the Cape Winelands to see some of its most historic wine estates and cellars. We will get in touch with nature at Bushmans Kloof Wilderness Reserve, a South African Natural Heritage Site. Bushmans Kloof is a sanctuary to more than 130 ancient Bushman rock art sites and home to many endangered species of flora and fauna. Exhilarating activities include nature drives and walks, canoeing and swimming in rock pools. Our next stop is the seaside town of Plettenberg Bay, a special treat for nature lovers, surrounded by ocean, lagoons, untamed forest, and lush countryside, with monumental mountains rising gracefully in the background. We will take a boat trip to see dolphins and visit pristine beaches, walk in the beautiful Featherbed Nature Reserve and visit bird and elephant sanctuaries. We end in Kwazulu-Natal, steeped in history and literally littered with battlefields; vestiges of the struggles of the Zulu Civil Wars and the clashes between the Boers and the British. -

October 2009 Newsletter

October 2009 http://www.wildlifedisease.org Jenny Powers, Editor Newsletter of the Wildlife Disease Association Members’ Corner 2009 WDA International Conference accepted an invitation from our president Charles van Ed Addison Riper to return and join us for our salmon barbecue th picnic the following evening. We very much appreci- The 58 Annual International Conference of the Wildlife ated the participation of the Rausch and Steele fami- Disease Association was held at the Semiahmoo Resort, lies. near Blaine, Washington, USA, 2-7 August 2009. The resort was located overlooking the ocean on a long sand The science program included approximately 132 oral spit only meters south of the Canada-U.S. border. presentations and 40 poster presentations. The social program included a fine welcoming reception; an ex- There were 273 registrants for the conference, one of cellent barbecue salmon picnic on the edge of the the largest number of attendees for WDA conferences. beach; the traditional WDA auction to raise funds for The participation of 27 registrants from Australia, Nation- student awards and activities; a half day of field excur- alist China, Korea, South Africa, United Arab Emirates, sions either whale watching, salmon fishing or river France, Switzerland, Swe- rafting; and our Thursday banquet. den, Spain and the Nether- Inside this issue lands enriched the diversity Drs. Buffy Howerth and Dave Stallknecht were both of topics presented. We presented with the WDA Distinguished Service Award recognize that it takes in recognition to their long and productive service to WDA News 3 added effort to attend by the Association in a wide variety of capacities, includ- those participants from out- ing their soon to be completed five year term as co- side of North America and editors of the Journal of Wildlife Diseases. -

Experience Management in the National Zoological Gardens of South Africa

EXPERIENCE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS OF SOUTH AFRICA By Maurice Craig Allenby Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MPhil in Tourism Management in the FACULTY OF ECONOMIC AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA Supervisor Dr Felicite Fairer-Wessels Date of submission April 2014 © University of Pretoria FACULTY OF ECONOMIC AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES Declaration Regarding Plagiarism The Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences emphasises integrity and ethical behaviour with regard to the preparation of all written assignments. Although the lecturer will provide you with information regarding reference techniques, as well as ways to avoid plagiarism, you also have a responsibility to fulfil in this regard. Should you at any time feel unsure about the requirements, you must consult the lecturer concerned before submitting an assignment. You are guilty of plagiarism when you extract information from a book, article, web page or any other information source without acknowledging the source and pretend that it is your own work. This does not only apply to cases where you quote the source directly, but also when you present someone else’s work in a somewhat amended (paraphrased) format or when you use someone else’s arguments or ideas without the necessary acknowledgement. You are also guilty of plagiarism if you copy and paste information directly from an electronic source (for example, a web site, e-mail message, electronic journal article, or CD-ROM) without paraphrasing it or placing it in quotation marks, even if you acknowledge the source. You are not allowed to submit another student’s previous work as your own. -

Visitors' Attitudes Toward Non-Human Primates in a Free

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 30 July 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202107.0684.v1 1 Visitors’ attitudes toward non-human primates in a free-roaming multi-species 2 sanctuary (Monkeyland, South Africa) 3 4 Christian Lenzi1, Chiara Grasso1*, Siobhan Speiran2 5 1 Associazione ETICOSCIENZA, Turin, Italy - [email protected] 6 2 The Lives of Animals Research Group, School of Environmental Studies, 7 Queen's University, 99 University Ave, Kingston, ON K7L 3N6 - [email protected] 8 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 9 10 The aim of the present study is to investigate themes related to visitors’ perceptions of captive 11 wildlife in particular, attitudes towards non-human primates (henceforth, primates). This 12 research took place in free-roaming, multi-species primate sanctuary, Monkeyland (South 13 Africa), where 400 visitors were interviewed using an anonymous survey both before and after 14 attending a guided tour. The answers were divided into different categories, in order to 15 standardize the motivations behind tourists’ choices. The results of the survey demonstrated 16 that most visitors agree that a primate would not be a good companion animal. Visitors’ desire 17 to touch primates was found to be positively correlated with desire for companion primates and 18 inversely associated with visitor age. In response to: “would you like to touch a monkey?”, the 19 majority of tourists who expressed this desire seemed aware that such interactions are not 20 appropriate, with concern for animal welfare and human health. Of the various primate species 21 present in the sanctuary, visitors preferred the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) and, generally 22 speaking, expressed appreciation for primates’ “cuteness”. -

The Rare Bali Starling | Birds of Eden the Largest Free Flight Bird Aviary in the World, Plettenberg Bay Activities Garden Route Adventures South Africa

9/24/13 The rare Bali Starling | Birds of Eden the largest free flight bird aviary in the world, Plettenberg Bay Activities Garden Route Adventures South Africa about Birds of Eden » The Rare Bali Starling about our birds about our forest » visit our sanctuaries bird feature news » photo album links » glossary contact us home A bird's heart beats 400 times per minute while they are at rest. When they are flying however, Leucopsar rothschildi their heart could beat up to 1000 beats per minute. The Bali Starling, also known as Rothschild’s Mynah, Bali Myna, or Bali Mynah is a medium-sized (up to 25 cm long), stocky myna, almost wholly white with a long, drooping crest, and black tips on the wings and tail. The bird has blue bare skin around the eyes, greyish legs and a yellow bill. Both sexes are similar. Naming Placed in the monotypic genus Leucopsar, it appears to be most closely related to Sturnia and the Brahminy Starling which is currently placed in Sturnus but will probably soon be split therefrom as Sturnus as presently delimited is highly paraphyletic (Jønsson & Fjeldså 2006). The specific name commemorates the British ornithologist Lord Rothschild. Distribution The Bali Starling is restricted to the island of Bali in Indonesia, where it is the island's only endemic vertebrate species. (An endemic subspecies, the Bali Tiger, has been extinct since 1937.) The bird was discovered in 1910, and in 1991 was designated the fauna symbol of Bali. Its local name is jalak Bali . Behaviour In its natural habitat however it is far less conspicuous, using tree tops for cover and–unlike other starlings–usually coming to the ground only to drink; this would seem to be an adaptation to the fact that it is instantly noticeable to predators when out in the open. -

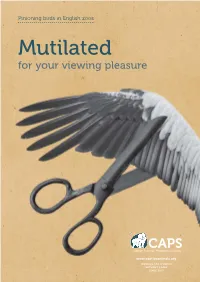

Mutilated for Your Viewing Pleasure. Pinioning Birds In

Pinioning birds in English zoos Mutilated for your viewing pleasure CAPS Captive Animals’ Protection Society www.captiveanimals.org WORKING FOR A WORLD WITHOUT CAGES SINCE 1957 Mutilated for your viewing pleasure In zoos and wildlife parks up and down the country, thousands of birds stand in large open enclosures, serenely surveying their surroundings. Flamingos pick their way delicately through shallow water and cranes stand on slender legs watching the world go by. The occasional flurry of wings flapping is seen but, strangely, none of the birds take flight. Are these birds simply content with their surroundings, choosing to stay conveniently within the boundaries of the zoo? Do they fly away at times and simply choose to return, safe in the knowledge they will find food in abundance and familiar flock mates? Is it a deep connection to their keepers that stops them from taking to the air? Or is it something else that holds these birds in the unnatural environment of a UK zoo? Look closely as wings are spread and you will find the answer... CAPS Captive Animals’ Protection Society PO Box 540, Salford, M5 0DS, UK Phone: +44 (0)845 330 3911 (local-call rate) or +44 (0)161 869 0020 E-mail: [email protected] Websites: www.captiveanimals.org www.irishcircuses.org The Captive Animals' Protection Society is a registered charity in England and Wales No.1124436 At just a few days old, thousands of birds in UK zoos have the end of one wing deliberately severed. • These birds will never fly. • These birds will never be released to the wild. -

South Africa 2018/19 Environment, Forestry and Fisheries

OFFICIAL GUIDE TO South Africa 2018/19 Environment, Forestry and Fisheries 99 Official Guide to South Africa 2018/19 Environment, Forestry and Fisheries 100 Following the reconfiguration of government departments in June 2019, the Department of the Environment, Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) was established after transferring the functions of forestry and fisheries from the then Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (now called Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development). Chapter 5 of the National Development Plan (NDP) emphasises the importance of environmental sustainability for robust socio-economic development. This is given expression by outcome 4 (decent employment through inclusive growth) and outcome 10 (protect and enhance our environmental assets and natural resources) of government’s 2014-2019 Medium Term Strategic Framework. Government prioritises the management, protection and conservation of South Africa’s environment and natural resources. According to Statistics South Africa’s General Household Survey (GHS) of 2018, waste removal problems and littering (42,6%), as well as land degradation and soil erosion (32,7%), were the two environmental problems that concerned the highest percentage of households in 2018. Strikingly, the percentage of households that considered land degradation and soil erosion a problem increased from 15,6% in 2003 to 34,1% in 2014 before dropping slightly to 32,7% in 2018. The proportion of households that felt that there were problems with littering and waste removal in their areas also increased notably since 2003 when 28,7% of households regarded this as a problem. Households that considered air pollution to be a problem decreased from 22,7% in 2003 to 18,9% in 2018. -

2Nd Congress of the European Federation for Primatology

Abstracts Folia Primatol 2008;79:305–401 Published online: June 13, 2008 DOI: 10.1159/000137690 2nd Congress of the European Federation for Primatology Prague, September 3–7, 2007 Editors: Vaclav Vancata and Marina Vancatova, Prague, Czech Republic Do Capuchin Monkeys (Cebus apella) Deal with Tokens as They Do with Real Food? Elsa Addessia , Alessandra Mancini a, b , Lara Crescimbenea , b , Elisabetta Visalberghi a a Unit of Cognitive Primatology and Primate Centre, Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, CNR, Rome, b Università La Sapienza, Rome, Italy E-Mail: [email protected] Key Words: Transitivity ؒ Cebus apella ؒ T o k e n s Recent studies on the use of tokens (i.e., inherently non-valuable objects that acquire an associated value upon exchange for food with an experimenter) in non-human primates did not investigate whether individuals use tokens as symbols. Therefore, we evaluated this topic in capuchin monkeys. We trained 10 capuchins to associate two types of tokens (A and B) with different amounts of food. Then, we assessed performance in relative numerousness judgment tasks with food (Experiment 1) and with tokens A (Experiment 2). In both experiments, all ca- puchins chose the highest quantity regardless of the type of item presented. Then, in Experi- ment 3 one token B was presented against 1–5 tokens A. Four capuchins used a flexible strategy, maximizing their payoff. Experiment 4 required the capuchins to choose between 1 and 2 to- kens B, and 3 and 6 tokens A. Only one subject always maximized his payoff in this task. -

Setting a Standard for the Future of All Sanctuaries

SETTING A STANDARD FOR THE FUTURE OF ALL SANCTUARIES Nestled in the heart of the beautiful Garden Route are three uniquely different sanctuaries; Monkeyland Primate Sanctuary, Birds of Eden and Jukani Wildlife Sanctuary. These sanctuaries come under the umbrella of the South Africa Animal Sanctuary Alliance (SAASA). SAASA takes the welfare of the animals and birds in their care very seriously and without exception. Therefore, Monkeyland, Birds of Eden and Jukani all abide by very exacting standards, ensuring the utmost quality of care together with promoting responsible tourism. In recognition of their high standards, SAASA has recently been awarded the highly acclaimed award, ‘Best Major Tourist Attraction’ in the SKAL International ‘Sustainable in Tourism Awards’ and furthermore won the Gold Award for ‘Best Animal Welfare Initiative’ and overall winner for the ‘World Responsible Tourism’ award. It is not only the animals that benefit from SAASA’s approach, Monkeyland and Birds of Eden are also Fairtrade accredited which means that we also take great care of the environment and our staff. Monkeyland and Birds of Eden are the only primate and bird sanctuaries to receive this accreditation in South Africa and it is hoped Jukani will soon follow suit. All SAASA controlled sanctuaries have a strict ‘no touch’ policy. These are not petting zoos and their purpose is not primarily entertainment. They are sanctuaries in every sense of the word, where previously abused animals and birds can develop a freedom they never had before and without human interference e. Monkeys play with monkeys, birds flock with their own kind and cats live out the rest of their lives in blissful laziness. -

Amphibian Husbandry Resource Guide, Edition 2.0

Amphibian Husbandry Resource Guide Edited by: Vicky A. Poole, National Aquarium – Baltimore Shelly Grow, Association of Zoos & Aquariums Edition 2.0, 4 April 2012 For more information about AZA and its amphibian programs, visit http://www.aza.org/ConScience/Amphibians_Intro/ Table of Contents Foreword………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….3 Chapter 1: General Amphibian Husbandry……………………..……………………………………………….….4 Chapter 2: Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) for Amphibians………………….60 Chapter 3: Hygiene and Disease Management: Field and Captivity…………………………..119 Chapter 4: Amphibian Quarantine and Isolation Guidelines……………………………………….129 Chapter 5: Creating Isolation Spaces for Amphibian Programs ……...……………..………..143 Chapter 6: Amphibian Population Management Guidelines*…………………………………….200 Chapter 7: Amphibian Data Entry Guidelines **……………………………………………………………232 * This chapter has been previously published. The recommended citation is: Schad, K., (ed.). 2008. Amphibian Population Management Guidelines. Amphibian Ark Amphibian Population Management Workshop; 2007 December 10-11; San Diego, CA, USA. Amphibian Ark. 31 p. ** This chapter has been previously published. The recommended citation is: Schad, K., (ed.). 2010. Amphibian Data Entry Guidelines. Population Management Center, Lincoln Park Zoo. Chicago, IL, USA. 7 p. Acknowledgements: The editors would like to thank the following people for their assistance in editing and reviewing this document: Daniel Beckwith (John G. Shedd Aquarium), Joseph R. Mendelson III, Ph.D. (Zoo Atlanta),