Grooming Structure and Function Crustacea M Some Terrestrial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Philosciidae" (Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea)

Org. Divers. Evol. 1, Electr. Suppl. 4: 1 -85 (2001) © Gesellschaft für Biologische Systematik http://www.senckenberg.uni-frankfurt.de/odes/01-04.htm Phylogeny and Biogeography of South American Crinocheta, traditionally placed in the family "Philosciidae" (Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea) Andreas Leistikow1 Universität Bielefeld, Abteilung für Zoomorphologie und Systematik Received 15 February 2000 . Accepted 9 August 2000. Abstract South America is diverse in climatic and thus vegetational zonation, and even the uniformly looking tropical rain forests are a mosaic of different habitats depending on the soils, the regional climate and also the geological history. An important part of the nutrient webs of the rain forests is formed by the terrestrial Isopoda, or Oniscidea, the only truly terrestrial taxon within the Crustacea. They are important, because they participate in soil formation by breaking up leaf litter when foraging on the fungi and bacteria growing on them. After a century of research on this interesting taxon, a revision of the terrestrial isopod taxa from South America and some of the Antillean Islands, which are traditionally placed in the family Philosciidae, was performed in the last years to establish monophyletic genera. Within this study, the phylogenetic relationships of these genera are elucidated in the light of phylogenetic systematics. Several new taxa are recognized, which are partially neotropical, partially also found on other continents, particularly the old Gondwanian fragments. The monophyla are checked for their distributional patterns which are compared with those patterns from other taxa from South America and some correspondence was found. The distributional patterns are analysed with respect to the evolution of the Oniscidea and also with respect to the geological history of their habitats. -

Optimization of Culture Conditions of Porcellio Dilatatus (Crustacea: Isopoda) for Laboratory Test Development Isabel Caseiro,* S

Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 47, 285}291 (2000) Environmental Research, Section B doi:10.1006/eesa.2000.1982, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Optimization of Culture Conditions of Porcellio dilatatus (Crustacea: Isopoda) for Laboratory Test Development Isabel Caseiro,* S. Santos,- J. P. Sousa,* A. J. A. Nogueira,* and A. M. V. M. Soares* ? *Instituto Ambiente e Vida, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade de Coimbra, 3004-517 Coimbra, Portugal; -Escola Superior Agra& ria de Braganma, Instituto Polite& cnico de Braganma, Braganma, Portugal; and ? Departamento de Biologia, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal Received December 21, 1999 in a tiered approach for evaluating the e!ects of toxic This paper describes the experimental results for optimizing substances in terrestrial systems (RoK mbke et al., 1996). Most isopod culture conditions for terrestrial ecotoxicity testing. The studies use animals coming directly from the "eld or main- in6uence of animal density and food quality on growth and tained in the laboratory as temporary cultures for that reproduction of Porcellio dilatatus was investigated. Results indi- speci"c purpose. These procedures, however, do not "t the cate that density in6uences isopod performance in a signi5cant needs of regular use of these organisms for the evaluation of way, with low-density cultures having a higher growth rate and several anthropogenic actions in the terrestrial environment better reproductive output than medium- or high-density cul- that require the maintenance of laboratory cultures under tures. Alder leaves, as a soft nitrogen-rich species, were found to controlled conditions. By using cultured individuals the be the best-quality diet; when compared with two other food mixtures, alder leaves induced the best results, particularly in necessary number and type of animals (sex, age class) can be terms of breeding success. -

THE NAUTILUS (Quarterly)

americanmalacologists, inc. PUBLISHERS OF DISTINCTIVE BOOKS ON MOLLUSKS THE NAUTILUS (Quarterly) MONOGRAPHS OF MARINE MOLLUSCA STANDARD CATALOG OF SHELLS INDEXES TO THE NAUTILUS {Geographical, vols 1-90; Scientific Names, vols 61-90) REGISTER OF AMERICAN MALACOLOGISTS JANUARY 30, 1984 THE NAUTILUS ISSN 0028-1344 Vol. 98 No. 1 A quarterly devoted to malacology and the interests of conchologists Founded 1889 by Henry A. Pilsbry. Continued by H. Burrington Baker. Editor-in-Chief: R. Tucker Abbott EDITORIAL COMMITTEE CONSULTING EDITORS Dr. William J. Clench Dr. Donald R. Moore Curator Emeritus Division of Marine Geology Museum of Comparative Zoology School of Marine and Atmospheric Science Cambridge, MA 02138 10 Rickenbacker Causeway Miami, FL 33149 Dr. William K. Emerson Department of Living Invertebrates Dr. Joseph Rosewater The American Museum of Natural History Division of Mollusks New York, NY 10024 U.S. National Museum Washington, D.C. 20560 Dr. M. G. Harasewych 363 Crescendo Way Dr. G. Alan Solem Silver Spring, MD 20901 Department of Invertebrates Field Museum of Natural History Dr. Aurele La Rocque Chicago, IL 60605 Department of Geology The Ohio State University Dr. David H. Stansbery Columbus, OH 43210 Museum of Zoology The Ohio State University Dr. James H. McLean Columbus, OH 43210 Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History 900 Exposition Boulevard Dr. Ruth D. Turner Los Angeles, CA 90007 Department of Mollusks Museum of Comparative Zoology Dr. Arthur S. Merrill Cambridge, MA 02138 c/o Department of Mollusks Museum of Comparative Zoology Dr. Gilbert L. Voss Cambridge, MA 02138 Division of Biology School of Marine and Atmospheric Science 10 Rickenbacker Causeway Miami, FL 33149 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF The Nautilus (USPS 374-980) ISSN 0028-1344 Dr. -

Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 63(2) 1996

July 1996 Number 2 Of of Washington A semiannual journal of research devoted to Helminthology and all branches of Parasitology Supported in part by the Brayton H. Ransom Memorial Trust Fund D. C. KRITSKY, W. A. :B6EC3ER, AND M, JEGU. NedtropicaliMonogehoidea/lS. An- — cyrocephalinae (Dactylogyridae) of Piranha and Their Relatives (Teleostei, JSer- rasalmidae) from Brazil and French Guiana: Species of Notozothecium Boeger and Kritsky, 1988, and Mymarotheciumgem. n. ..__ _______ __, ________ ..x,- ______ .s.... A. KOHN, C. P. SANTOS, AND-B. LEBEDEV. Metacdmpiella euzeti gen. n., sp, n., and I -Hargicola oligoplites~(Hargis, 1951) (Monogenea: Allodiscpcotylidae) from Bra- " zilian Fishes . ___________ ,:...L".. _______ j __ L'. _______l _; ________ 1 ________ _ __________ ______ _ .' _____ . __.. 176 C. P. SANTO?, T. SOUTO-PADRGN, AND R. M. LANFREDI. Atriasterheterodus (Levedev and Paruchin, 1969) and Polylabris tubicimts (Papema and Kohn, 1964) (Mono- ' genea) from Diplodus argenteus (Val., 1830) (Teleostei: Sparidae) from Brazil 181 . I...N- CAIRA AND T. BARDOS. Further Information on :.Gymnorhynchus isuri (Trypa- i/:norhyncha: Gymnorhynchidae) from the Shortfin Make Shark ...,.'. ..^_.-"_~ ____. ; 188 O. M. AMIN AND W. L.'MmcKLEY. Parasites of Some Fisji Introduced into an Arizona Reservoir, with Notes on Introductions — . ____ : ______ . ___.i;__ L____ _ . ______ :___ _ .193 O. M. AMIN AND O. SEY. Acanthocephala from Arabian Gulf Fishes off Kuwait, with 'Descriptions of Neoechinorhynchus dimorphospinus sp. n. XNeoechinorhyrichi- dae), Tegorhyrichus holospinosus sp. n. (l\lio&&ntid&e),:Micracanthorynchina-ku- waitensis sp. n. (Rhadinorhynchidae), and Sleriidrorhynchus breviclavipraboscis gen. n., sp. p. (Diplosentidae); and Key to Species of the Genus Micracanthor- . -

(Crustacea : Amphipoda) of the Lower Chesapeake Estuaries

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1971 The distribution and ecology of the Gammaridea (Crustacea : Amphipoda) of the lower Chesapeake estuaries James Feely Virginia Institute of Marine Science Marvin L. Wass Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Marine Biology Commons, Oceanography Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Feely, J., & Wass, M. L. (1971) The distribution and ecology of the Gammaridea (Crustacea : Amphipoda) of the lower Chesapeake estuaries. Special papers in marine science No.2. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. http://doi.org/10.21220/V5H01D This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DISTRIBUTION AND ECOLOGY OF THE GAMMARIDEA (CRUSTACEA: AMPHIPODA) OF THE LOWER CHESAPEAKE ESTUARIES James B. Feeley and Marvin L. Wass SPECIAL PAPERS IN MARINE SCIENCE NO. 2 VIRGIN IA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SC IE NCE Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1971 THE DISTRIBUTION AND ECOLOGY OF THE GAMMARIDEA (CRUSTACEA: AMPHIPODA) OF THE LOWER 1 CHESAPEAKE ESTUARIES James B. Feeley and Marvin L. Wass SPECIAL PAPERS IN MARINE SCIENCE NO. 2 1971 VIRGINIA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 This document is in part a thesis by James B. Feeley presented to the School of Marine Science of the College of William and Mary in Virginia in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. -

Crustacea, Oniscidea)

Carina Appel Análise e descrição de estruturas temporárias presentes no período ovígero de isópodos terrestres (Crustacea, Oniscidea). Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Instituto de Biociências da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Biologia Animal. Área de concentração: Biologia comparada Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Paula Beatriz de Araujo UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL PORTO ALEGRE 2011 Análise e descrição morfológica de estruturas temporárias presentes no período ovígero de isópodos terrestres (Crustacea, Oniscidea). Carina Appel Dissertação de mestrado aprovada em ______ de _______________ de _______. _____________________________________ Drª. Laura Greco Lopes _____________________________________ Drª. Suzana Bencke Amato _____________________________________ Drª. Carolina Coelho Sokolowicz II a Perfeição da Vida “Por que prender a vida em conceitos e normas?... ...Tudo, afinal, são formas...” “A resposta certa, não importa nada: o essencial é que as perguntas estejam certas.” Mário Quintana III Agradecimentos Ao encerrar esta etapa gostaria de lembrar e agradecer as pessoas e instituições que de alguma forma contibuíram para o desenvolvimento desta pesquisa. Assim, agradeço em primeiro lugar à minha orientadora, Profª. Paula, pela orientação, pelo incentivo, pelos ensinamentos compartilhados, pelo apoio nas horas difíceis, enfim por todo o carinho com que sempre me tratou. Obrigada do fundo do coração! À Aline que me auxiliou muitas vezes, obrigada pela paciência e atenção! Ao casal Buckup por toda a atenção, afeto, amizade, conselhos e conhecimentos compartilhados ao longo destes anos. Aos meus colegas e amigos Bianca, Ivan e Kelly, obrigada por todo o apoio, amizade e companheirismo, a amizade de vocês é algo que pretendo cultivar. -

Crustacea, Isopoda, Oniscidea) of the Families Philosciidae and Scleropactidae from Brazilian Caves

European Journal of Taxonomy 606: 1–38 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2020.606 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2020 · Campos-Filho et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY 4.0). Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:95D497A6-2022-406A-989A-2DA7F04223B0 New species and new records of terrestrial isopods (Crustacea, Isopoda, Oniscidea) of the families Philosciidae and Scleropactidae from Brazilian caves Ivanklin Soares CAMPOS-FILHO 1,*, Camile Sorbo FERNANDES 2, Giovanna Monticelli CARDOSO 3, Maria Elina BICHUETTE 4, José Otávio AGUIAR 5 & Stefano TAITI 6 1,5 Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia e Gestão de Recursos Naturais, Av. Aprígio Veloso, 882, Bairro Universitário, 58429-140 Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil. 2,4 Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Departamento de Ecologia e Biologia Evolutiva, Rodovia Washington Luis, Km 235, 13565-905 São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil. 3 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Departamento de Zoologia, Laboratório de Carcinologia, Av. Bento Gonçalves, 9500, Agronomia, 91510-979 Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. 6 Istituto di Ricerca sugli Ecosistemi Terrestri, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Via Madonna del Piano 10, 50019 Sesto Fiorentino (Florence), Italy. 6 Museo di Storia Naturale, Sezione di Zoologia “La Specola”, Via Romana 17, 50125 Florence, Italy. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] -

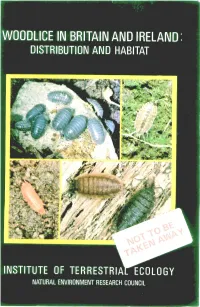

Woodlice in Britain and Ireland: Distribution and Habitat Is out of Date Very Quickly, and That They Will Soon Be Writing the Second Edition

• • • • • • I att,AZ /• •• 21 - • '11 n4I3 - • v., -hi / NT I- r Arty 1 4' I, • • I • A • • • Printed in Great Britain by Lavenham Press NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS ISBN 0 904282 85 6 COVER ILLUSTRATIONS Top left: Armadillidium depressum Top right: Philoscia muscorum Bottom left: Androniscus dentiger Bottom right: Porcellio scaber (2 colour forms) The photographs are reproduced by kind permission of R E Jones/Frank Lane The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to, and draws upon, the collective knowledge of the 13 sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man- made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. One quarter of ITE's work is research commissioned by customers, such as the Department of Environment, the European Economic Community, the Nature Conservancy Council and the Overseas Development Administration. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. ITE's expertise is widely used by international organizations in overseas projects and programmes of research. -

Orden Isopoda: Suborden Oniscidea

Revista IDE@ - SEA, nº 78 (30-06-2015): 1–12. ISSN 2386-7183 1 Ibero Diversidad Entomológica @ccesible www.sea-entomologia.org/IDE@ Clase: Malacostraca Orden ISOPODA: Oniscidea Manual CLASE MALACOSTRACA Orden Isopoda: Suborden Oniscidea Lluc Garcia *Museu Balear de Ciències Naturals, Sóller, Mallorca (Illes Balears) Imagen superior: Oniscus asellus. Fotografía LL. Garcia 1. Breve definición del grupo y principales caracteres diagnósticos 1.1. Morfología. Generalidades. Los isópodos terrestres (Oniscidea) son crustáceos eumalacostráceos pertenecientes al orden Isopoda, aunque reúnen una serie de características morfológicas y fisiológicas relacionadas con su modo de vida terrestre que permiten considerarlos como un grupo natural bien definido, considerado actualmente como monofilético (Schmidt, 2002, 2003, 2008). Como todos los representantes del orden, su cuerpo está dor- soventralmente aplanado y se divide en tres partes bien diferenciables a simple vista: 1. El céfalon, en el que sitúan los ojos, en la mayoría de los casos compuestos; dos pares de ante- nas; y el aparato masticador con un par de mandíbulas, que son asimétricas, y dos pares de maxilas. En los isópodos terrestres el céfalon está compuesto por la cabeza propiamente dicha y por el primer seg- mento del pereion, soldado a ésta y llamado también segmento maxilipedal por insertarse en él los maxilí- pedos, que cubren el resto de piezas bucales. La división entre este segmento y el resto de la cabeza es invisible en vista dorsal en la gran mayoría de isópodos terrestres aunque sí que es apreciable en forma surcos laterales que lo separan de la región cefálica. Por eso se debe considerar más propiamente como un cefalotórax. -

Bottom-Up Control of Parasites

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles 10-5-2017 Bottom-Up Control of Parasites David S. Johnson Virginia Institute of Marine Science, [email protected] Richard Heard Gulf Coast Research Laborartory Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Environmental Health Commons, and the Parasitology Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, David S. and Heard, Richard, "Bottom-Up Control of Parasites" (2017). VIMS Articles. 2. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bottom-up control of parasites 1, 2 DAVID SAMUEL JOHNSON AND RICHARD HEARD 1Department of Biological Sciences, The College of William and Mary, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, 1375 Greate Road, Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 USA 2Department of Coastal Sciences, Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, University of Southern Mississippi, 703 East Beach Street, Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39564 USA Citation: Johnson, D. S., and R. Heard. 2017. Bottom-up control of parasites. Ecosphere 8(10):e01885. 10.1002/ecs2.1885 Abstract. Parasitism is a fundamental ecological interaction. Yet we understand relatively little about the ecological role of parasites compared to the role of free-living organisms. Bottom-up theory predicts that resource enhancement will increase the abundance and biomass of free-living organisms. Similarly, para- site abundance and biomass should increase in an ecosystem with resource enhancement. We tested this hypothesis in a landscape-level experiment in which salt marshes (60,000 m2 each) received elevated nutri- ent concentrations via flooding tidal waters for 11 yr to mimic eutrophication. -

Benvenuto, C and SC Weeks. 2020

--- Not for reuse or distribution --- 8 HERMAPHRODITISM AND GONOCHORISM Chiara Benvenuto and Stephen C. Weeks Abstract This chapter compares two sexual systems: hermaphroditism (each individual can produce gametes of either sex) and gonochorism (each individual produces gametes of only one of the two distinct sexes) in crustaceans. These two main sexual systems contain a variety of alternative modes of reproduction, which are of great interest from applied and theoretical perspectives. The chapter focuses on the description, prevalence, analysis, and interpretation of these sexual systems, centering on their evolutionary transitions. The ecological correlates of each reproduc- tive system are also explored. In particular, the prevalence of “unusual” (non- gonochoristic) re- productive strategies has been identified under low population densities and in unpredictable/ unstable environments, often linked to specific habitats or lifestyles (such as parasitism) and in colonizing species. Finally, population- level consequences of some sexual systems are consid- ered, especially in terms of sex ratios. The chapter aims to provide a broad and extensive overview of the evolution, adaptation, ecological constraints, and implications of the various reproductive modes in this extraordinarily successful group of organisms. INTRODUCTION 1 Historical Overview of the Study of Crustacean Reproduction Crustaceans are a very large and extraordinarily diverse group of mainly aquatic organisms, which play important roles in many ecosystems and are economically important. Thus, it is not surprising that numerous studies focus on their reproductive biology. However, these reviews mainly target specific groups such as decapods (Sagi et al. 1997, Chiba 2007, Mente 2008, Asakura 2009), caridean Reproductive Biology. Edited by Rickey D. Cothran and Martin Thiel. -

(Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea) from Brazilian Caves

bs_bs_banner Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2014, 172, 360–425. With 40 figures Terrestrial isopods (Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea) from Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article-abstract/172/2/360/2433445 by Universidade de S�o Paulo user on 25 May 2020 Brazilian caves IVANKLIN SOARES CAMPOS-FILHO1*, PAULA BEATRIZ ARAUJO1, MARIA ELINA BICHUETTE2, ELEONORA TRAJANO3 and STEFANO TAITI4 1Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Departamento de Zoologia, Laboratório de Carcinologia, Av. Bento Gonçalves, 9500, Agronomia, 91510-070 Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 2Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Departamento de Ecologia e Biologia Evolutiva, Rodovia Washington Luis, Km 235, 13565-905 São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil 3Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Zoologia, Rua do Matão, trav. 14, n°. 321, Cidade Universitária, 05508-090 São Paulo, Brazil 4Istituto per lo Studio degli Ecosistemi, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Via Madonna del Piano 10, 50019 Sesto Fiorentino (Florence), Italy Received 16 December 2013; revised 5 May 2014; accepted for publication 8 May 2014 To date, six species of terrestrial isopods were known from Brazilian caves, but only four could be classified as troglobites. This article deals with material of Oniscidea collected in many Brazilian karst caves in the states of Pará, Bahia, Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso do Sul, and São Paulo, and deposited in the collections of the Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo, the Coleção de Carcinologia do Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, and the collection of the Natural History Museum, Section of Zoology ‘La Specola’, Flor- ence.