Evaluation on the Effect of Microfinance on Poor Rural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridges Across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia

Bridges across Oceans Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia April 2010 0 2010 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2010. Printed in the Philippines ISBN 978-971-561-896-0 Publication Stock No. RPT101731 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Bridges across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2010. 1. Transport Infrastructure. 2. Southeast Asia. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB encourages printing or copying information exclusively for personal and noncommercial use with proper acknowledgment of ADB. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of ADB. Note: In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 -

Prevalence and Natural History of X-Linked Dystonia Parkinsonism In

A Publication of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute Original Article Prevalence and Natural History of X-Linked Dystonia Parkinsonism in Koronadal City, South Cotabato Michael Dorothy Frances Montojo-Tamayo *1, Rachel Suarez-Uy 2, Donna Mae Lyn Buhat 3, Jeffrey Tamayo 4, Roland Dominic Jamora 5 1The Medical City, Ortigas Avenue, Pasig City; 2Dr. Arturo P. Pingoy Medical Center, Koronadal City, South Cotabato; 3St. Anthony Medical Hospital, Marikina City; 4Roel I Senador Memorial Hospital, South Cotabato; 5Movement Disorders Center and Section of Neurology, International Institute for Neurosciences, St Luke’s Medical Center –Quezon City and Global City, Philippines *Contact Details: [email protected] ABSTRACT: X-linked dystonia Parkinsonism (XDP) is an adult-onset, progressive, debilitating movement disorder, mani- festing predominantly with dystonia in combination with Parkinsonism. It was first reported in 1975 among males in Panay Island. Migrants from Panay Island occupied the region of South Cotabato in Mindanao with its capital Koronadal City. The estimated population of the region is 912,957 as of 2015 and the dominant ethnicity, comprising 51%, are from Panay Island. This paper calls attention to this migration and aimed to identify cases and describe the clinical picture of XDP in Koronadal City. A descriptive study using the screening questionnaire for XDP was used per barangay to look for possible cases. Cases were confirmed through interview and assessment by a movement disorder specialist. Four cases of XDP from Koronadal City were seen. They were all male, presenting with generalized dystonia. The phenomenology of these cases is similar to the 2011 study involving 312 patients. -

Indigenous People and Situation Analysis

CALL FOR PROPOSALS Technical Assistance on the Mapping of, and situation analysis of Indigenous People (IP), Collectively or Individually in SNIP 2 project sites (Aklan, Agusan del Sur and Davao Region) 1. Summary The World Health Organization (WHO) Philippines through the Subnational Initiative Project, Phase 2 (SNIP2) is looking for an individual or institution contractual partner to provide technical assistance on the mapping of, and situation analysis of Indigenous People (IP) in project sites, one APW each for Aklan, Agusan del Sur and Davao Region under an Agreement for Performance of Work (APW) contract. The applications are due by 5 September 2021. 2. Background The World Health Organization Philippines Country Office is currently implementing the Subnational Initiative Project Phase 2 in collaboration with the Philippines Department of Health and with funding support from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). The project is called “Strengthening Health Care Provider Network (HCPN) with Enhanced Linkage to Community for Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCAH). The objective is to improve the health systems of the three (3) regions for better health for maternal, child, and adolescent health. The project will respond based on the following health outcomes; supported communities to develop effective approaches to essential health services for RMNCAH, strengthened governance and management for the responsiveness of HCPN, and sustained and scaled up the initial gains in Region XI from the Subnational Initiative Phase 1 Project. Especially in Phase 2, participation of community level is one of the main activities and this can be achieved through engagement and empowerment of Municipal and Barangay level including indigenous people (IP). -

SEC 16. Transfer of Existing Facilities and Intangible Assets

FOURTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC ) OF THE PHILIPPINES ) 7 IIil -7 First Regular Session 1 INTRODUCED BY SEN. JINGGOY EJERCITO ESTRADA EXPLANATORY NOTE The world famous resort Boracay of the Province of Aklan is one of the top tourist destinations of the Philippines. Business activities also flourish in the area to cater to foreign and local visitors. Records show that volume of passenger air traffic flying the Kalibo-Manila- Kalibo, Manila-Caticlan-Manila and Kalibo-Cebu-Kalibo routes have steadily grown. There are now also a number of airlines operating along these routes. Hence, the need to improve, expand and upgrade the facilities in the two airports including night landing and all weather airport equipment and system. This bill seeks to achieve this by establishing the “Aklan Airport Authority” which shall have the power to administer and operate the Kalibo and Catiklan airports in the Province of Aklan. The approval of this bill is earnestly sought. NGGO EJERCITO ESTRAD Senator P FOURTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC ) OF THE PHILIPPINES ) 7 Jill--' First Regular Session 1 INTRODUCED BY SEN. JlNGGOY EJERCITO ESTRADA AN ACT CREATING THE AKLAN AIRPORT AUTHORITY, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of fhe Philippines in Congress assembled: SECTION 1. Title. This Act shall be known and cited as the "Charter of the Aklan Airport Authority". SEC 2. Creation of the Aklan Airport Authority. There is hereby established a body corporate to be known as the Aklan Airport Authority which shall be attached to the Department of Transportation and Communications. -

Binanog Dance

Gluck Classroom Fellow: Jemuel Jr. Barrera-Garcia Ph.D. Student in Critical Dance Studies: Designated Emphasis in Southeast Asian Studies Flying Without Wings: The Philippines’ Binanog Dance Binanog is an indigenous dance from the Philippines that features the movement of an eagle/hawk to the symbolic beating of bamboo and gong that synchronizes the pulsating movements of the feet and the hands of the lead and follow dancers. This specific type of Binanog dance comes from the Panay-Bukidnon indigenous community in Panay Island, Western Visayas, Philippines. The Panay Bukidnon, also known as Suludnon, Tumandok or Panayanon Sulud is usually the identified indigenous group associated with the region and whose territory cover the mountains connecting the provinces of Iloilo, Capiz and Aklan in the island of Panay, one of the main Visayan islands of the Philippines. Aside from the Aetas living in Aklan and Capiz, this indigenous group is known to be the only ethnic Visayan language-speaking community in Western Visayas. SMILE. A pair of Binanog dancers take a pose They were once associated culturally as speakers after a performance in a public space. of the island’s languages namely Kinaray-a, Akeanon and Hiligaynon, most speakers of which reside in the lowlands of Panay and their geographical remoteness from Spanish conquest, the US invasion of the country, and the hairline exposure they had with the Japanese attacks resulted in a continuation of a pre-Hispanic culture and tradition. The Suludnon is believed to have descended from the migrating Indonesians coming from Mainland Asia. The women have developed a passion for beauty wearing jewelry made from Spanish coins strung together called biningkit, a waistband of coins called a wakus, and a headdress of coins known as a pundong. -

Aklan Province

GENDER AND DEVELOPMENT LOCAL LEARNING HUBS Men advocates of MOVE-Aklan take a stand against VAWC Aklan Province ocal government units (LGUs) doing gender with the unique contexts and specific needs of LGUs, the mainstreaming need strong leadership and Philippine Commission on Women (PCW) then “localized” Lcommitment, organized women’s groups, adequate its Technical Assistance Blueprint in accordance with resources — and lots of inspiration — to see things gender-related mandates and as provided for by the through. In fact, when gender mainstreaming is not Magna Carta of Women (RA 9710). explicitly defined in the LGUs’ development plans, Gender and Development (GAD) efforts may not be In 2014, PCW added the GAD Local Learning Hubs realized at all. As a form of assistance and in keeping up (GAD LLHs) to its LGU-centered technical assistance portfolio, the aim of which is to showcase innovative Center for Women (ACCW). Since its establishment in GAD structures, processes, and programs that have 2001, the ACCW served as a 24-hour receiving and been sustained if not improved by LGUs through the action center for walk-ins, referrals, and rescued women years. GAD LLHs are meant for sharing and replicating and children under crisis — even to those from nearby good practices, ultimately giving other LGUs the provinces. Having learned from a decade of operations, opportunity to think outside the box when implementing the Child Protection Unit (CPU) was later organized to GAD initiatives. LGUs seeking to imbibe GAD innovations bolster ACCW’s counseling services, referral functions, can learn from the GAD LLHs and get inspiration on how and economic support for women survivors. -

MAKING the LINK in the PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment

MAKING THE LINK IN THE PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment The interconnected problems related to population, are also disappearing as a result of the loss of the country’s health, and the environment are among the Philippines’ forests and the destruction of its coral reefs. Although greatest challenges in achieving national development gross national income per capita is higher than the aver- goals. Although the Philippines has abundant natural age in the region, around one-quarter of Philippine fami- resources, these resources are compromised by a number lies live below the poverty threshold, reflecting broad social of factors, including population pressures and poverty. The inequity and other social challenges. result: Public health, well-being and sustainable develop- This wallchart provides information and data on crit- ment are at risk. Cities are becoming more crowded and ical population, health, and environmental issues in the polluted, and the reliability of food and water supplies is Philippines. Examining these data, understanding their more uncertain than a generation ago. The productivity of interactions, and designing strategies that take into the country’s agricultural lands and fisheries is declining account these relationships can help to improve people’s as these areas become increasingly degraded and pushed lives while preserving the natural resource base that pro- beyond their production capacity. Plant and animal species vides for their livelihood and health. Population Reference Bureau 1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, Suite 520 Washington, DC 20009 USA Mangroves Help Sustain Human Vulnerability Coastal Communities to Natural Hazards Comprising more than 7,000 islands, the Philippines has an extensive coastline that is a is Increasing critical environmental and economic resource for the nation. -

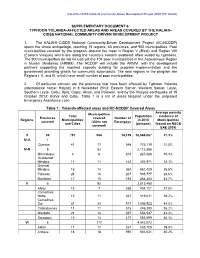

Supplementary Document 6: Typhoon Yolanda-Affected Areas and Areas Covered by the Kalahi– Cidss National Community-Driven Development Project

KALAHI–CIDSS National Community-Driven Development Project (RRP PHI 46420) SUPPLEMENTARY DOCUMENT 6: TYPHOON YOLANDA-AFFECTED AREAS AND AREAS COVERED BY THE KALAHI– CIDSS NATIONAL COMMUNITY-DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 1. The KALAHI–CIDDS National Community-Driven Development Project (KC-NCDDP) spans the whole archipelago, reaching 15 regions, 63 provinces, and 900 municipalities. Poor municipalities covered by the program abound the most in Region V (Bicol) and Region VIII (Eastern Visayas) which are along the country’s eastern seaboard often visited by typhoons. The 900 municipalities do not include yet the 104 poor municipalities in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The NCDDP will include the ARMM, with the development partners supporting the required capacity building for program implementation and the government providing grants for community subprojects. The new regions in the program are Regions I, II, and III, which have small number of poor municipalities. 2. Of particular concern are the provinces that have been affected by Typhoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) in 8 November 2013: Eastern Samar, Western Samar, Leyte, Southern Leyte, Cebu, Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, and Palawan, and by the Visayas earthquake of 15 October 2013: Bohol and Cebu. Table 1 is a list of areas targeted under the proposed Emergency Assistance Loan. Table 1: Yolanda-affected areas and KC-NCDDP Covered Areas Average poverty Municipalities Total Population incidence of Provinces covered Number of Regions Municipalities in 2010 Municipalities -

Here at Aklan State University Main Campus in Banga This July 4-6, 2019

1 We encourage you to use the website and mobile app for current information and to navigate the Symposium. Changes to the scientific program will be published on an addendum that will be posted on messages board. 2 In line with this year’s theme, the logo symbolizes the strategic cooperation between the scientific community and the different facets of the local institutions and the government to achieve wholesome and sustainable seas. The lower half signifies the ocean while the upper half shows the diversity of marine life and its interconnectivity with food security and environmental resilience. The halves meet at the center forming a handshake embodying the common understanding of the local communities, government, academe, private sector, NGOs, and especially the Filipino masses on the protection, management, and holistic conservation of the oceans. Lastly, the hues used also represent the colors of the sea at the break of dawn, signifying a new chapter for a more hopeful, science-based, and community- oriented future of the Philippine seas. Best logo design for PAMS15 Mr. John Michael Lastimoso 3 SYMPOSIUM SPONSORS 4 Welcome Message It is with great pleasure and excitement that we, the Philippine Association of Marine Science Officers 2017-2019, welcome you to the 15th National Symposium in Marine Science at the Aklan State University, Banga, Aklan on July 4-6, 2019 with the theme “Fostering synergy of science, community and governance for healthy seas.” As PAMS continues to undertake the task of promoting growth in marine science in the country, the PAMS15 will focus on highlighting the complex people-sea relationship and look more closely on the ways by which we can address the growing issues and risks to food security, biodiversity, and community resilience. -

Ati, the Indigenous People of Panay: Their Journey, Ancestral Birthright and Loss

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Dance MFA Student Scholarship Dance 5-2020 Ati, the Indigenous People of Panay: Their Journey, Ancestral Birthright and Loss Annielille Gavino Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/dancemfastudents Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons HOLLINS UNIVERSITY MASTER OF FINE ARTS DANCE Ati, the Indigenous People of Panay: Their Journey, Ancestral Birthright and Loss Monday, May 7, 2020 Annielille Gavino Low Residency Track- Two Summer ABSTRACT: This research investigates the Ati people, the indigenous people of Panay Island, Philippines— their origins, current economic status, ancestral rights, development issues, and challenges. This particular inquiry draws attention to the history of the Ati people ( also known as Aetas, Aytas, Agtas, Batak, Mamanwa ) as the first settlers of the islands. In contrast to this, a festive reenactment portraying Ati people dancing in the tourism sponsored Dinagyang and Ati-Atihan festival will be explored. This paper aims to compare the displacement of the Ati as marginalized minorities in contrast to how they are celebrated and portrayed in the dance festivals. Methodology My own field research was conducted through interviews of three Ati communities of Panay, two Dinagyang Festival choreographers, and a discussion with cultural anthropologist, Dr. Alicia P. Magos, and a visit to the Museo de Iloilo. Further data was conducted through scholarly research, newspaper readings, articles, and video documentaries. Due to limited findings on the Ati, I also searched under the blanket term, Negrito ( term used during colonial to post colonial times to describe Ati, Aeta, Agta, Ayta,Batak, Mamanwa ) and the Austronesians and Austo-Melanesians ( genetic ancestor of the Negrito indigenous group ). -

Iloilo Antique Negros Occidental Capiz Aklan Guimaras

Sigma Kalibo Panitan Makato Handicap International Caluya PRCS - IFRC Don Bosco Network Ivisan PRCS - IFRC Humanity First Tangalan CapizNED CapizNED Don Bosco Network PRCS - IFRC CARE Supporting Self Recovery PRAY PRCS - IFRC IOM Citizens’ Disaster Response Center New Washington CapizNED IOM Region VI Humanity First Caritas Austria Don Bosco Network PRAY PRAY of Shelter Activities Malay PRAY World Vision Numancia PRCS - IFRC Humanity First PRCS - IFRC Buruanga IOM PRCS - IFRC by Municipality (Roxas) PRCS - IFRC Nabas Buruanga Don Boxco Network Balasan Pontevedra Altavas Roxas City PRCS - IFRC Ibajay HEKS - TFM 3W map summary Nabas Libertad IOM Region VI Caritas Austria IOM R e gion VI World Vision PRCS - IFRC CapizNED Tangalan CapizNED World Vision Citizens’ Disaster Response Center Produced April 14, 2014 Pandan PRAY Batad Numancia Don Bosco Network IOM Region VI CARE IRC Makato PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC Malinao Makato Kalibo Panay MSF-CH Don BoSco Network Batan Humanity First Humanity First This map depicts data PRCS - IFRC Lezo IOM Caritas Austria Relief o peration for Northern Iloilo World Vision Lezo PRCS - IFRC CapizNED Solidar Suisse gathered by the Shelter CARE PRCS - IFRCNew Washington IOM Region VI Pilar Cluster about agencies Don Bosco Network HEKS - TFM Malinao HEKS - TFM Carles who are responding to Sebaste Banga Caritas Austria IOM Region VI PRAY DFID - HMS Illustrious Sebaste World Vision Welt Hunger Hilfe Typhoon Yolanda. PRCS - IFRC Concern Worldwide IOM Banga Citizens’ Disaster Response CenterRoxas City Humanity First IOM Region VI Batan Humanity First MSF-CH Carles Any agency listed may Citizens’Panay Disaster Response Center Save the Children Region VI Altavas Ivisan ADRA Ayala Land have projects at different Madalag AklanBalete SapSapi-Ani-An stages of completion (e.g. -

PRIVATE SECTOR INITIATED POWER PROJECTS (VISAYAS) INDICATIVE As of 31 October 2020

PRIVATE SECTOR INITIATED POWER PROJECTS (VISAYAS) INDICATIVE As of 31 October 2020 Committed / Indicative Name of the Project Project Proponent Location Rated Capacity (MW) Project Status Target Testing & Commissioning Target Commercial Operation COAL 600 FEASIBILITY STUDY • Pre-engineering activities (Topo, Bathymetry & Soil Investigation and etc.) in progress Indicative SMC Loboc Malabuyoc Coal-Fired Power Plant Project SMC Global Power Holdings Corp. Mactan, Cebu 300 TBD TBD 'PERMITS AND OTHER REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS: • Issued with SIS 24 July 2017 (DOE-EPIMB-SIS No. 2018-06-004) FEASIBILITY STUDY • Pre-engineering activities (Topo, Bathymetry & Soil Investigation and etc.) in progress Indicative SMC Global Negros Coal-Fired Power Plant Project SMC Global Power Holdings Corp. San Carlos, Negros Occidental 300 'PERMITS AND OTHER REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS: TBD TBD • Issued with SIS 12 January 2015 (DOE-EPIMB-SIS No. 2015-01-005) NATURAL GAS 0 OIL-BASED 37.2 FEASIBILITY: •on-going ARRANGEMENT DOE SECURING THE REQUIRED LAND: •N/A (to be built inside the existing plant. MARKET OF GENERATING CAPACITIES: •Coordination/consultancy with NGCP (reserve capacity off-taker). 'PERMITS AND OTHER REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS: Indicative Bohol Diesel Power Plant Capacity Expansion SPC Island Power Corporation Tagbilaran, Bohol 30 August 2021 November 2021 •Issued with SIS 12 March 2019 (DOE-EPIMB-SIS No. 2019-03-001); ECC on-going.; SIS on-going. ESTIMATED NUMBER OF JOBS GENERATED: •During Construction: 40 jobs and During Operation: 30 jobs GROUNDBREAKING SCHEDULES: February 2021 (target) FINANCING ARRANGEMENTS: Self-financed CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTS FOR PLANTS AND EQUIPMENT: Under negotiation ISSUES ENCOUNTERED RE: PROJECT DEVELOPMENT: No Advanced Contracting and Market and Regilatory Conditions PERMITS AND OTHER REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS: •Secured all rquired permits and clearance from various government agencies.