Ptsc 3/2 the Evolution of Wisdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8113-Yasham Neden Var-Nick Lane-Ebru Qilic-2015-318S.Pdf

KOÇ ÜNiVERSiTESi YAYINLARI: 87 BiYOLOJi Yaşam Neden Var? Nick Lane lngilizceden çeviren: Ebru Kılıç Yayına hazırlayan: Hülya Haripoğlu Düzelti: Elvan Özkaya iç rasarım: Kamuran Ok Kapak rasarımı: James Jones The Vital Question © Nick Lane, 2015 ©Koç Üniversiresi Yayınları, 2015 1. Baskı: lsranbul, Nisan 2016 Bu kitabın yazarı, eserin kendi orijinal yararımı olduğunu ve eserde dile getirilen rüm görüşlerin kendisine air olduğunu, bunlardan dolayı kendisinden başka kimsenin sorumlu rurulamayacağını; eserde üçüncü şahısların haklarını ihlal edebilecek kısımlar olmadığını kabul eder. Baskı: 12.marbaa Sertifika no: 33094 Naro Caddesi 14/1 Seyranrepe Kağırhane/lsranbul +90 212 284 0226 Koç Üniversiresi Yayınları lsriklal Caddesi No:181 Merkez Han Beyoğlu/lsranbul +90 212 393 6000 [email protected] • www.kocuniversirypress.com • www.kocuniversiresiyayinlari.com Koç Universiry Suna Kıraç Library Caraloging-in-Publicarion Dara Lane, Nick, 1967- Yaşam neden var?/ Nick Lane; lngilizceden çeviren Ebru Kılıç; yayına hazırlayan Hülya Haripoğlu. pages; cm. lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-605-5250-94-2 ı. Life--Origin--Popular works. 2. Cells. 1. Kılıç, Ebru. il. Haripoğlu, Hülya. 111. Tirle. QH325.L3520 2016 Yaşam Neden Var? NICKLANE lngilizceden Çeviren: Ebru Kılıç ffi1KÜY İçindeki le� Resim Listesi 7 TEŞEKKÜR 11 GiRİŞ 17 Yaşam Neden Olduğu Gibidir? BiRİNCi BÖLÜM 31 Yaşam Nedir? Yaşamın ilk 2 Milyar Yılının Kısa Ta rihi 35 Genler ve Doğal Ortamla ilgili Sorun 39 Biyolojinin Kalbindeki Kara Delik 43 Karmaşıklık Yo lunda Kayıp Adımlar -

Understanding Adaptation in Large Populations

Perspective Understanding Adaptation in Large Populations Nick Barton* Institute of Science and Technology (IST) Austria, Klosterneuburg, Austria For the past half-century, population independent of whatever long-term factors a surrounding genome whose diversity genetics has been dominated by studies determine neutral diversity. Resistance to depends only on the number of favour- of molecular evolution, interpreted under organophosphate insecticides is due to able mutations that enter in every gener- the neutral theory. This predicts that the specific amino-acid changes in the active ation, 2Nm, and whose length depends on rate of substitution equals the rate of site of the target enzyme acetyl-cholines- the inverse of the time to fixation, ,S/ neutral mutation and that the genetic terase, with the most resistant alleles log(S/m) (Figure 1). diversity within populations depends on having three changes. Karasov et al. show In very large populations, the distinc- the product of population size and that although the same amino acids tion between adaptation from new muta- neutral mutation rate, 4Nm.Yet,diver- (indeed, because of constraints from the tions—invoked here by Karasov et al. sity clearly does not increase in direct genetic code, the same nucleotide changes) [5]—and adaptation from standing varia- proportion to population size [1,2]. are always involved, these have arisen tion becomes blurred. If there is selection s Bacterial populations are typically more independently many times on different against resistance alleles before insecticide diverse than insects, which in turn are local haplotypes. Most striking is that is applied, then resistance alleles will be more diverse than mammals, but these complex resistance alleles have arisen present at a frequency of ,m/s, and each differences span only an order of magni- through successive mutations, with no allele will have originated on average tude, even though actual population sizes need for recombination, and all within ,1/s generations back; in this example, vary far more. -

Editor's Note

Volume 8: Issue 1 (2021) Editor’s Note CONTENTS Dear ICA Members, Editor’s Note .................. 1 Welcome to 2021! We are now a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, and with vaccines on the market, we are seeing the light at the end Meetings, of the tunnel. Announcements, and Calls for Papers .............. 3 The ICA Interest group will be meeting at this year’s virtual SAA Research Highlights ....... 4 meeting on April 16 from 12-1 PM EDT. Please join us to learn more about the group, get involved, and network with colleagues. All are Lapidary artwork in the welcome! Amerindian Caribbean, a regional, open, online Over the past year, there have been over 1000 new publications in database and GIS ....... 4 81 different journals in our field. In addition, several new books have The La Sagesse been published, four of which are featured in our “Recent Community Publications” section. The quantity and quality of new literature attests to the fact that, despite the pandemic, island and coastal Archaeology Project research is thriving. (LCAP) in Grenada, West Indies ................ 6 As always, please continue to send us your new publications. While Recent Publications ....... 7 we do not rely exclusively on sources sent to us by our members, we usually receive at least one member submission from a journal that Featured New Books: 7 we missed in our biannual literature review. Your submissions help Journals Featuring to provide publicity for your work and assists us in putting together a Recent Island and more thorough bibliography each cycle. Coastal Archaeology Papers: ....................... 8 The last issue of the Current appeared when wildfires and political scandal dominated news headlines, and coastal archaeologists faced New Papers in the reports of accelerating sea level rise. -

Directory 2016/17 the Royal Society of Edinburgh

cover_cover2013 19/04/2016 16:52 Page 1 The Royal Society of Edinburgh T h e R o Directory 2016/17 y a l S o c i e t y o f E d i n b u r g h D i r e c t o r y 2 0 1 6 / 1 7 Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Limited, Dorchester, DT1 1HD ISSN 1476-4334 THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH DIRECTORY 2016/2017 PUBLISHED BY THE RSE SCOTLAND FOUNDATION ISSN 1476-4334 The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street Edinburgh EH2 2PQ Telephone : 0131 240 5000 Fax : 0131 240 5024 email: [email protected] web: www.royalsoced.org.uk Scottish Charity No. SC 000470 Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Limited CONTENTS THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH .....................................................3 COUNCIL OF THE SOCIETY ..............................................................5 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE ..................................................................6 THE RSE SCOTLAND FOUNDATION ..................................................7 THE RSE SCOTLAND SCIO ................................................................8 RSE STAFF ........................................................................................9 LAWS OF THE SOCIETY (revised October 2014) ..............................13 STANDING COMMITTEES OF COUNCIL ..........................................27 SECTIONAL COMMITTEES AND THE ELECTORAL PROCESS ............37 DEATHS REPORTED 26 March 2014 - 06 April 2016 .....................................................43 FELLOWS ELECTED March 2015 ...................................................................................45 -

John Maynard Smith Archive (1948-2004) (Add MS 86569-86840) Table of Contents

British Library: Western Manuscripts John Maynard Smith Archive (1948-2004) (Add MS 86569-86840) Table of Contents John Maynard Smith Archive (1948–2004) Key Details........................................................................................................................................ 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................................... 2 Provenance........................................................................................................................................ 2 Add MS 86569–86574 Reprints and copies of articles and book chapters by John Maynard Smith (1952–2003)...................................................................................................................................... 3 Add MS 86575–86596 Correspondence files, F–Z (1975–1991).............................................................. 5 Add MS 86597–86830 Subject files (1948–2003).................................................................................. 18 Add MS 86831–86835 Notebooks and plant lists (1973–2003)............................................................... 223 Add MS 86836–86837 Lecture notes ([c 1990–c 1999])........................................................................ 226 Add MS 86838–86839 Artefacts and books (1983–2001)....................................................................... 227 Add MS 86840 Annotations and manuscripts with offprints received by John Maynard Smith (1952?–2003)................................................................................................................................... -

The Barrier to Genetic Exchange Between Hybridising Populations

Heredity 56 (1986) 357—376 The Genetical Society of Great Britain Received 13 February 1986 The barrier to genetic exchange between hybridising populations Nick Barton* and * Departmentof Genetics and Biometry, University College London, 4 Stephenson Way, London Bengt Olle Bengtssont NW1 2HE, U.K. tDepartmentof Genetics, University of Lund, Sölvegatan 29, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden. Suppose that selection acts at one or more loci to maintain genetic differences between hybridising populations. Then, the flow of alleles at a neutral marker locus which is linked to these selected loci will be impeded. We define and calculate measures of the barrier to gene flow between two distinct demes, and across a continuous habitat. In both cases, we find that in order for gene flow to be significantly reduced over much of the genome, hybrids must be substantially less fit, and the number of genes involved in building the barrier must be so large that the majority of other genes become closely linked to some locus which is under selection. This conclusion is not greatly affected by the pattern of epistasis, or the position of the marker locus along the chromosome. INTRODUCTION neutral. This selection pressure will only cease after the incoming alleles have recombined away from Theseparation of biological species requires the their old genetic background. The rate of flow of evolution of genetic barriers to gene exchange. a neutral marker into the new population will Thus, to understand the process of speciation, we therefore depend on the ratio between selection at need to know not only how genetic differences the "barrier locus", and recombination between evolve, but also the effect these differences have that locus and the marker locus. -

Sarah Perin Otto

Curriculum Vitae SARAH PERIN OTTO Address: Mail: Department of Zoology University of British Columbia 6270 University Boulevard Vancouver BC V6T 1Z4, CANADA Phone: (604) 822-2778 FAX: (604) 822-2416 E-mail: [email protected] Personal: Nickname: Sally Citizenship: United States & Canadian Education and Work Experience: Current position: Full Professor, Killam University Professor & Canada Research Chair (Tier I), Department of Zoology; 2000-2005: Associate Professor, Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia 1995-2000: Assistant Professor, Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia 1994-1995: SERC Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, University of Edinburgh, UK Sponsor: N. Barton 1992-1994: Miller Post-Doctoral Fellow, UC Berkeley, Berkeley, CA Department of Integrative Biology Sponsors: G. Thomson, M. Slatkin 1988-1992: Ph. D., Stanford University, Stanford, CA Department of Biological Sciences Committee: M. W. Feldman (advisor), L. L. Cavalli-Sforza, J. Roughgarden Thesis: Evolution in Sexual Organisms: The Role of Recombination, Ploidy Level, and Nonrandom Mating 1990: Complex Studies Summer School, Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM 1989,1991: Lab rotation (two semesters), Harvard University, Harvard, MA Advisor: R. C. Lewontin 1985-1988: B.Sc. with honors in Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA Advisors: V. Walbot, M. W. Feldman 1985: International Baccalaureate Degree, Washington International School Grant and Fellowship Support: 1. Discovery grant, Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council, Canada (2016-2021) C$92,000 per annum 2. International Research Roundtable grant, Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies (2015-2016) C$38,720 total 3. Discovery grant, Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council, Canada (2010-2015) C$82,000 per annum 4. Discovery Accelerator grant, Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council, Canada (2010-2013) C$40,000 per annum 5. -

Epistasis Can Facilitate the Evolution of Reproductive Isolation by Peak Shifts: a Two-Locus Two-Allele Model

Copyright 0 1994 by the Genetics Society of America Epistasis Can Facilitate the Evolution of Reproductive Isolation by Peak Shifts: A Two-Locus Two-Allele Model Andreas Wagner,* Giinter P. Wagner* and Philippe Similiont “Yale University, Department of Biology, Center for Computational Ecology, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8104 and Yale University, Department for Applied Physics, Becton Center, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-2157 Manuscript received October 13, 1993 Accepted for publication July 8, 1994 ABSTRACT The influence of epistasis on the evolution of reproductive isolation by peak shifts is studied in a two-locus two-allele model of a quantitative genetic character under stabilizing selection. Epistasis is in- troduced by a simple multiplicative term in the function that maps gene effects onto genotypic values. In the model with only additive effects on the trait, the probability of a peak shift and the amount of reproductive isolation are always inverselyrelated, i. e., the higherthe peak shift rate, thelower the amount of reproductive isolation caused by the peak shift. With epistatic characters there is no consistent rela- tionship between these two values. Interestingly, there are cases where both transition rates as well as the amount of reproductive isolation are increased relative to the additive model. This effect has two main causes: a shift in the location of the transition point, and the hybrids between the two alternative optimal genotypes have lower average fitnessin the epistatic case. A review of the empirical literature shows that the fitness relations resulting in higher peak shift rates and more reproductive isolation are qualitatively the same as those observed for genes causing hybrid inferiority. -

How Does Epistasis Influence the Response to Selection&Quest;

Heredity (2017) 118, 96–109 & 2017 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 0018-067X/17 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE How does epistasis influence the response to selection? NH Barton Much of quantitative genetics is based on the ‘infinitesimal model’, under which selection has a negligible effect on the genetic variance. This is typically justified by assuming a very large number of loci with additive effects. However, it applies even when genes interact, provided that the number of loci is large enough that selection on each of them is weak relative to random drift. In the long term, directional selection will change allele frequencies, but even then, the effects of epistasis on the ultimate change in trait mean due to selection may be modest. Stabilising selection can maintain many traits close to their optima, even when the underlying alleles are weakly selected. However, the number of traits that can be optimised is apparently limited to ~4Ne by the ‘drift load’, and this is hard to reconcile with the apparent complexity of many organisms. Just as for the mutation load, this limit can be evaded by a particular form of negative epistasis. A more robust limit is set by the variance in reproductive success. This suggests that selection accumulates information most efficiently in the infinitesimal regime, when selection on individual alleles is weak, and comparable with random drift. A review of evidence on selection strength suggests that although most variance in fitness may be because of alleles with large Nes, substantial amounts of adaptation may be because of alleles in the infinitesimal regime, in which epistasis has modest effects. -

Sewall Wright on Evolution in Mendelian Populations and the “Shifting Balance”

| CLASSIC Sewall Wright on Evolution in Mendelian Populations and the “Shifting Balance” Nicholas H. Barton1 Institute of Science and Technology Austria, A-3400 Klosterneuburg, Austria ORIGINAL CITATION Evolution in Mendelian Populations Sewall Wright GENETICS March 1, 1931 16: 97–159 fter the rediscovery of Mendel’s work in 1900, bitter similarrates ofselection,migration,and randomdrift.This would Adisputes erupted between the first geneticists and the allow more efficient exploration of the “adaptive landscape.” biometricians who studied quantitative traits. How could the Wright’stheorywashighlyinfluential, stimulating many discrete genes of the geneticists explain the continuous var- studies of natural population structure. Nevertheless, it is iation observed by biometricians? And could natural selec- not clear that his “shifting balance” mechanism actually tion shape variation in these genes? Eventually, the two operates in nature (Coyne et al. 1997). As Fisher argued, a camps came to understand that quantitative variation is changing environment allows continual evolution across the due to multiple Mendelian genes of small effect, and selec- vast space of possible genotypes (see Provine 1986 for the tion on this variation is highly effective. Yet in 1931, very few correspondence between Fisher and Wright on these issues). attempts had been made to formally describe the genetics of The roles of local fitness peaks and gene flow in adaptive evolving populations. By explicitly reconciling Mendel’s and evolution remain major open questions in evolutionary biol- Darwin’s theories, Sewall Wright and the other pioneers of ogy, nearly a century after Wright first raised the issue. population genetics laid an enduring mathematical founda- Communicating editor: C. -

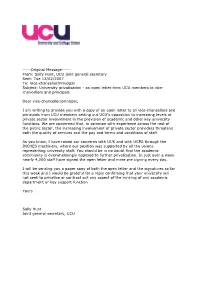

Tue 13/02/2007 To: Vice-Chancellor/Principal Subject: University Privatisation - an Open Letter from UCU Members to Vice- Chancellors and Principals

-----Original Message----- From: Sally Hunt, UCU joint general secretary Sent: Tue 13/02/2007 To: Vice-chancellor/Principal Subject: University privatisation - an open letter from UCU members to vice- chancellors and principals Dear vice-chancellor/principal, I am writing to provide you with a copy of an open letter to all vice-chancellors and principals from UCU members setting out UCU's opposition to increasing levels of private sector involvement in the provision of academic and other key university functions. We are concerned that, in common with experience across the rest of the public sector, the increasing involvement of private sector providers threatens both the quality of services and the pay and terms and conditions of staff. As you know, I have raised our concerns with UUK and with UCEA through the JNCHES machinery, where our position was supported by all the unions representing university staff. You should be in no doubt that the academic community is overwhelmingly opposed to further privatisation. In just over a week nearly 4,500 staff have signed the open letter and more are signing every day. I will be sending you a paper copy of both the open letter and the signatures so far this week and I would be grateful for a reply confirming that your university will not seek to privatise or contract out any aspect of the running of any academic department or key support function Yours Sally Hunt Joint general secretary, UCU An open letter to vice-chancellors and principals from UCU members We are writing to you to let you know of UCU's opposition to increasing levels of private sector involvement in the provision of academic and other key university functions. -

Volume 6, Issue 2

Volume 1: Issue 2/2 2018 CONTENTS Editor’s Note Dear ICA Members, Editor’s Note ............ 1 Happy New Year! We are pleased to announce the launch of the Island and Coastal Archaeology Interest Group e- Meetings, Communities webpage, which is automatically accessible to all Announcements & interest group members through the SAA’s newly updated Calls for Papers ........ 3 website. The e-Communities page is a venue to share and discuss new articles, workshops, grant opportunities, field methods, and laboratory analyses. It is also intended as a Research Highlight ... 6 venue to help coordinate events during annual meetings and to distribute interest group newsletters. When you have the Recent opportunity, please visit our e-Communities webpage and the Publications ............ 7 SAA e-Community Rules of Engagement. We hope the e- Communities platform will make it easier for ICA members to Submission communicate with one another and make us a tighter-knit and more engaged research community. Instructions ............ 57 The list of 550 recent publications demonstrates the breadth and depth of work taking place globally. Island and coastal archaeologists continue to be at forefront of knowledge concerning human-environment relationships in the past. However, there are also a number of publications highlighting aspects of ancient communities’ social and artistic lives. Especially notable is the amount of work coming from the underwater and maritime archaeology segment of our community. The word “shipwreck” alone occurs in the titles of thirteen publications from the list. If you have recent publications that have not appeared in one of our past issues, we encourage you to submit these for inclusion in our next issue.