UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

In the World, Brien Engel Is One of the Most Musically Accomplished

About Brien and Glass Harp Music: Among the very few professional glass harpists in the world, Brien Engel is one of the most musically accomplished. His glass harp is comprised of fi�y drinking glasses which are coaxed to astonishing musical life by his fingers. Brien delights audiences everywhere with singular mastery of his instrument, an outstanding repertoire of music for all se�ngs and warm stage presence. Brien has performed in countless K-12 schools across the na�on and in libraries, nightclubs, senior communi�es, fes�vals and college campuses. He has toured in Germany, Singapore, Hong Kong, HARP Dubai and Kuwait. Read the bio on the web site: www.glassharp.org GLASS Youtube Channel: Brien Engel On Facebook: Brien Engel – Glass Harp ENGEL (404) 633-9322 [email protected] BRIEN MEET THE ARTIST DETAILS: WHAT: For the five-day package, two op�onal half-hour “Meet the Ar�st” sessions are offered for students and teachers using Google Meet or Zoom conferencing, to supplement the movie Distance/Virtual Programming for ‘20-’21 and wrap up the program. Or one session, for the half-day package. WHEN: Half-hour Concert/Documentary offered: Over the period of access to movie, or as closely �med as possible. At the facilitator’s discre�on for best scheduling, but subject to ar�st’s calendar too. Brien Engel presents a brand new half-hourConcert/Documentary: “The Glass Harp and other Musical Oddi�es” (<--click for 3-min. preview) as part of WHAT HAPPENS: a distance learning package. The full movie will be accessible via secure link for either five days, or one half-day, to a school. -

Jason Robinson and Anthony Davis Dates Available in 2012-2014

Jason Robinson and Anthony Davis dates available in 2012-2014 “[For Robinson and Davis,] mood and interplay are more important than volume or scale.” -Ron Wynn, JazzTimes Magazine “[A] consummate summation of the jazz tradition in its most conversational and fundamental form.” -Troy Collins, All About Jazz “almost Ellingtonian in their lapidary elegance and beauty, highlighting the richness of Davis’ chordal voicings and Robinson’s big, brawny, Ben Webster-ish tone on tenor.” -The Stash Dauber “[I]nspired by their mutual passion for the music of Duke Ellington and spohisticated blues forms in a variety of hues, [their duet] is by turns lyrical and edgy, inviting and challenging. It’s steeped in jazz traditions that are handily extended, which is Robinson’s raison d’etre for making music.” -George Varge, San Diego Union-Tribune Moody, stark, and emotionally charged. Captured on their critically acclaimed debut recording Cerulean Landscape (Clean Feed, 2010), Robinson and pianist Anthony Davis have collaborated for more than ten years as a duo. Telepathic interplay, inspired improvisation, and dynamic original compositions carry listeners to a brilliant and evocative soundscape marked by emotional subtlety, a vast array of sounds, and poignant melodicism. With Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, and the post- 60s jazz avant-garde as central reference points, Robinson and Davis bring together their formidable experience in many different music worlds, spilling over the traditional boundaries of the horn/piano duo. One moment minimalist, another orchestral, another beautifully melodic – their duo invites us into a sound world of deep blues, a place of surreal horizons, intense emotions, and hypnotic melodies. -

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager����� Lewis, George E

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager Lewis, George E. Leonardo Music Journal, Volume 10, 2000, pp. 33-39 (Article) Published by The MIT Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lmj/summary/v010/10.1lewis.html Access Provided by University of California @ Santa Cruz at 09/27/11 9:42PM GMT W A Y S WAYS & MEANS & M E A Too Many Notes: Computers, N S Complexity and Culture in Voyager ABSTRACT The author discusses his computer music composition, Voyager, which employs a com- George E. Lewis puter-driven, interactive “virtual improvising orchestra” that ana- lyzes an improvisor’s performance in real time, generating both com- plex responses to the musician’s playing and independent behavior arising from the program’s own in- oyager [1,2] is a nonhierarchical, interactive mu- pears to stand practically alone in ternal processes. The author con- V the trenchancy and thoroughness tends that notions about the na- sical environment that privileges improvisation. In Voyager, improvisors engage in dialogue with a computer-driven, inter- of its analysis of these issues with ture and function of music are active “virtual improvising orchestra.” A computer program respect to computer music. This embedded in the structure of soft- ware-based music systems and analyzes aspects of a human improvisor’s performance in real viewpoint contrasts markedly that interactions with these sys- time, using that analysis to guide an automatic composition with Catherine M. Cameron’s [7] tems tend to reveal characteris- (or, if you will, improvisation) program that generates both rather celebratory ethnography- tics of the community of thought complex responses to the musician’s playing and indepen- at-a-distance of what she terms and culture that produced them. -

Brian Baldauff Treatise 11.9

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Percussion Music of Michael W. Udow: Composer Portrait and Performance Analysis of Selected Works Brian C. (Brian Christopher) Baldauff Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE PERCUSSION MUSIC OF MICHAEL W. UDOW: COMPOSER PORTRAIT AND PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS OF SELECTED WORKS By BRIAN C. BALDAUFF A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2017 Brian C. Baldauff defended this treatise on November 2, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: John W. Parks IV Professor Directing Treatise Frank Gunderson University Representative Christopher Moore Committee Member Patrick Dunnigan Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To Shirley. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document and degree would not have been possible without the support, guidance, and patience of numerous extraordinary individuals. My wife, Caitlin for her unwavering encouragement. Dr. John W. Parks IV, my major professor, Dr. Patrick Dunnigan, Dr. Christopher Moore, and Dr. Frank Gunderson for serving on my committee. All my friends and colleagues from The Florida State University, the University of Central Florida, the University of Michigan, West Liberty University, and the University of Wisconsin- Stevens Point for their advice and friendship. My parents Sharon and Joe, and all my family members for their love. -

How to Play the Musical

' '[! . .. ' 1 II HOW TO PLAY THE MUSI CAL SAW by RENE ' BOGART INTRODUCTION TO PLAYING THE MUSICA L SAW: It is unknown just when nor where THE MUSICAL SAW had it's origin and was first played. It ~s believed among some MUSICAL SAW players, however, that i t originated in South America in the 1800's and some believe the idea was imported into the U. S. from Europe . I well remember the fi r st time I heard it played. It wa s in Buffalo, N.Y. and played at the Ebrwood M!L6,£.c..Ha..U about 1910 when I was a boy. It has been used extensively in the ho me, on stage at private cl ubs, church fun ctions, social gatherings , hospita l s and nursing homes, in vaudevi l le and theaters for years, and more recently on Radio and Televisi on Programs in the enter tainmentfield. The late Cf.alte.nc..e.MM ~e.ht , of Fort Atkinson, Wi sconsin, was the first to introduce and suppl y Musical Saw Kits to the field under the name of M!L6 ~e. ht&Wutpha1.,** and did a great deal to develop the best line of SAWS suitable for this use, after considerable research. Before taking up the MUSICAL SAW and going into the detail s of there quired proceedure for playing it wel l , it is important to understand some of the basic rudiments and techniques involved for it's proper manipu l ation. While the MUSICAL SAW is essential l y a typi cal carpenter's or craftsman's saw, it' s use as a very unique musical instrument has gained in popu larity, and has recently become a means of expressing a very distinctive qua l ity of music. -

TIRESIAN SYMMETRY (Cuneiform Rune 346) Format: CD

Bio information: JASON ROBINSON Title: TIRESIAN SYMMETRY (Cuneiform Rune 346) Format: CD Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: 301-589-8894 / fax 301-589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / AVANT-JAZZ Saxophonist/Composer Jason Robinson Takes a Mythic Journey with New Album: Tiresian Symmetry featuring Robinson with All-Star Band: George Schuller, Ches Smith, Marty Ehrlich, Liberty Ellman, Drew Gress, Marcus Rojas, Bill Lowe, JD Parran A ubiquitous and often pivotal figure in the stories and myths of ancient Greece, the blind prophet Tiresias was blessed and cursed by the gods, experiencing life as both a man and a woman while living for hundreds of years. In saxophonist/composer Jason Robinson’s polydirectional masterpiece Tiresian Symmetry, he doesn’t seek to tell the soothsayer’s story. Rather for his seventh album as a leader, he’s gathered an extraordinary cast of improvisers to investigate the nature of narrative itself in a jazz context. The music’s richly suggestive harmonic and metrical relationships elicit a wide array of responses, but ultimately listeners find their own sense of order and meaning amidst the sumptuous sounds. For Robinson, a capaciously inventive artist who has flourished in a boggling array of settings, from solo excursions with electronics and free jazz quartets to roots reggae ensembles and multimedia collectives, Tiresian Symmetry represents his most expansive project yet. “I was attracted to the myth of the soothsayer, who tells the future even when it’s not welcome information,” Robinson says. “But on a more technical level I was intrigued by the numerical relationships. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO How Music Travels: the Opera Blood Hunger Child a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfac

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO How Music Travels: the Opera Blood Hunger Child A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Jon Forshee Committee in charge: Professor Anthony Davis, Chair Professor Katharina Rosenberger, Co-Chair Professor Norman Bryson Professor Amy Cimini Professor Aleck Karis Professor Lei Liang 2017 Copyright Jon Forshee, 2017. All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Jon Forshee is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………….……………………………iii Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………….iv List of Supplemental Files……………….…………..…………………………….…...v List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………...vi Vita……………………………………………………………………………….…..….vii Abstract of the Dissertation……………………………………………………...…...viii How Music Travels - The Opera Blood, Hunger, Child: Introduction…….…………1 Chapter 1: Sources and Background……….………………………………………...7 Chapter 2: The Story….……………………………………………………...………..15 Chapter 3: The Libretto in Verse…..………………………………………………… 19 Chapter 4: Vocal Types and Orchestration….……………………………………….31 Chapter 5: Transcription as Creative Practice...…………………………………….34 Chapter 6: Esu-Legba and the Orisha…...………………………………………….36 Chapter 7: The Story within the Story……………………………………………….54 References…………………………………………………………………………..…58 iv LIST OF SUPPLEMENTAL FILES Blood | Hunger | Child, Chamber Opera -

Percussion Instruments

Series In Popular Science - Vol. 3 SCIENCE OF PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS THOMAS D. ROSSING World Scientific S C I E N C E O F PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS SERIES IN POPULAR SCIENCE Editor-in-Chief: Richard J. Weiss Published Vol. 1 A Brief History of Light and Those That Lit the Way by Richard J. Weiss Vol. 2 The Discovery of Anti-matter: The Autobiography of Carl David Anderson, the Youngest Man to Win the Nobel Prize by C. D. Anderson Series in Popular Science - Vol. 3 SCIENCE O F PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS THOMAS D. ROSSING Northern Illinois University World Scientific `1 Singapore • New Jersey. London • Hong Kong Published by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. P O Box 128, Farrer Road, Singapore 912805 USA office: Suite 1B, 1060 Main Street, River Edge, NJ 07661 UK office: 57 Shelton Street, Covent Garden, London WC2H 9HE British Library Cataloguing -in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. First published 2000 Reprinted 2001 SCIENCE OF PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS Series in Popular Science - Volume 3 Copyright m 2000 by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof may not be reproduced in anyform or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permissionfrom the Publisher. For photocopying of material in this volume, please pay a copying fee through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. In this case permission to photocopy is not required from the publisher. -

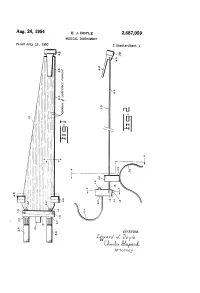

Aug. 24, 1954 E

Aug. 24, 1954 E. J. DOYLE 2,687,059 MUSICAL INSTRUMENT Filed July 12, 1950 2 Sheets-Sheet l Poy?eINVENTOR. Attorney Aug. 24, 1954 E. J. DOYLE 2,687,059 MUSICAL INSTRUMENT Filed July 12, 1950 2 Sheets-Sheet 2 | 8 NY 16 14. a2a2a22ZZZZZZZZ2 N NNS N F. E.E. fo Aaward / ZeyteINVENTOR, Y Caule as hepard Attorney Patented Aug. 24, 1954 2,687,059 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 2,687,059 MUSICAL INSTRUMENT Edward J. Doyle, Brighton, N.Y. Application July 12, 1950, Serial No. 173,330 Claims. (Cl. 84-402) 1. 2 The present invention relates to musical in or holding parts do not greatly damp the vibra struments and more particularly to the type in tions of the metal blade and yet do not them which a resonant metal body is vibrated While Selves vibrate to a sufficient extent to give rise the player manipulates its tension to produce a to undesirable Sounds of their own. Scale of musical notes as in the well known The butt or Wider end of the blade has an “musical saw' where an ordinary carpenter's abrupt reverse taper at 2, the extremity of saw is variously bent and struck with a mallet . which portion enters a kerf 4 in a cross bar 6 or similar percussion device or otherwise vibrated. Wherein it is tightly clamped by end bolts i8 The general object of this invention is to provide Which, it will be observed, are removed from con a simple but improved instrument of this charac 0. tact With the blade which throughout, has no ter that will be more convenient to hold and play metal to metal contacts. -

Eastman Opera Theatre

EASTMAN OPERA THEATRE OUR VOICES Wednesday, December 16, 2020 — 7:30 PM THE GREATEST LIBERTY with selected arias by Anthony Davis Thursday, December 17, 2020 — 7:30 PM HEART MELODIES music by Ricky Ian Gordon Friday, December 18, 2020 — 7:30 PM I SHALL NOT LIVE IN VAIN music of Lori Laitman Saturday, December 19, 2020 — 2:00 PM THIS WORLD WITHIN ME with selections from Song from the Uproar by Missy Mazzoli Saturday, December 19, 2020 — 7:30 PM THE JOURNEY TOWARDS FREEDOM with selected songs and arias by Ben Moore Sunday, December 20, 2020 — 2:00 PM THE JOURNEY TO HERE with songs by Errollyn Wallen ARTISTIC TEAM Artistic Director Music Director Steven Daigle Timothy Long Associate Artistic Director Assistant Music Director Stephen Carr Wilson Southerland Instructor of Opera Candidate for M.M. Opera Stage Directing Lindsay Warren Baker Madeleine Snow Graduate Assistant Collaborative Pianists Rebecca Golub Jenny Kirby Ava Linvog Evan Ritter PRODUCTION TEAM Production Designers Costume Designer Lighting Designer Daniel Hobbs Carly Holzwarth Nic Minetor Charles Murdock Lucas* Technical Director Sound Designer Production Stage Manager Mark Houser Rich Wattie Josh Lau Scenic Construction & Artists** Costumes & Wardrobe Ramon Rivera Claudette Hercules Jose Maisonet Leah Camilleri Nicole LaClair MaryPat Frohm Mountain House Media, Film Editors Andrew Sevigny Jeremiah Gryczka Nate Bellavia Matt Lombardo * United Scenic Artists, Local USA 829 of the IATSE is the union representing Scenic, Costume, Lighting, Sound, and Projection designers in Live Performance ** Additional Stage Hands provided by IATSE Local-25 CONCEPT OF OUR VOICES Eastman Opera Theatre has responded to the challenges of social distancing by focusing on the creative process through intimate, one-on- one musical collaborations with prominent composers for the voice and lyric stage. -

Creative Musical Instrument Design

CREATIVE MUSICAL INSTRUMENT DESIGN: A report on experimental approaches, unusual creations and new concepts in the world of musical and sound instruments. A thesis submitted to the SAE Institute, London, in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Recording Arts, awarded by Middlesex University. Author: Andrea Santini Student: 42792 Intake: RAD0503X Project Tutors: Christopher Hayne Darren Gash London, August 2004 c r e a t i v e m u s i c a l i n s t r u m e n t d e s i g n Abstract The following document presents the results of an investigation into the current reality of creative musical-instrument and sound-instrument design. The focus of this research is on acoustic and electro-acoustic devices only, sound sources involving oscillators, synthesis and sampling, be it analogue or digital, have therefore been excluded. Also, even though occasional reference will be made to historical and ‘ethnical’ instruments, they will not be treated as a core issue, the attention being primarily centered on contemporary creations. The study includes an overview of the most relevant “sonic creations” encountered in the research and chosen as representative examples to discuss the following aspects: o Interaction between body and instrument. o Sonic Space o Tuning and layout of pitches o Shapes, materials and elements o Sonic objects, noise and inharmonic sources o Aesthetics: sound instruments as art objects o Amplification and transducer technologies These where chosen to provide some degree of methodology during the research process and a coherent framework to the analysis of a subject which, due to its nature and to the scarcity of relevant studies, has unclear boundaries and a variety of possible interdisciplinary connections.