Ofsted Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caroline Benn

Caroline Benn: Champion of Democratic Education Jane Martin Department of Education and Social Justice, College of Social Science, University of Birmingham 21 June 2016 Caroline Benn Timeline 1926 Born October 13, Cincinnati, Ohio Ohio River flood 1937 1948 Graduates from Vassar College Meets Tony Benn 2 August Marries Tony Benn 17 June 1949 1951 Gives birth to her first child, Stephen; completes University of London MA Gives birth to her second child, Hilary 1953 1957 Gives birth to her third child, Melissa Gives birth to her fourth child, Joshua 1958 1962 Her novel Lion in a Den of Daniels published Labour Party win general election 1964 1965 Comprehensive Schools Committee Editor Comprehensive Education Reads Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White on 1966 Jackanory, BBC 1970 Chair of governors, Holland Park School Member Inner London Education Authority Co-author Half Way There: Report on the British Comprehensive School Reform (with Brian Simon) President Socialist Education Association 1973 1978 UNESCO Education Commissioner Television film, Carry On Comprehensives 1980 1982 Co-author Higher Education for Everyone Editor & contributor to National Labour Movement 1987 Inquiry Into Youth Unemployment & Training 1992 Author Keir Hardie: a biography Co-author Thirty Years On: is comprehensive 1996 education alive and well or struggling to survive? (with Clyde Chitty) 1998 Retires as governor of Holland Park School Dies at Charing Cross hospital, London, 22 2000 November “Caroline Benn was educated in the USA and Britain, and teaches in adult education. Since 1965 she has been the editor of Comprehensive Education and research officer of the national Campaign for Comprehensive Education. -

Your Kensington Schools Guide Selected Local Schools

Your Kensington Schools Guide Selected Local Schools Lycée Français Charles de Gaulle Chepstow House School An independent school for 3,660 boys and girls aged An independent school for 320 boys and girls aged from 3 to 19. from 2 to 13. The Good Schools Guide says… The Good Schools Guide says… This is a huge institution yet parents say children are With red carpet throughout, it feels more like a large, happy, well taught and love the cultural diversity. glamorous chalet than any school we’ve been to. Over the years, the Lycée has spread and now occupies Lots of smiling faces, on both parents and children when a city block across from the Natural History Museum. they arrive first thing. Kiss and Drop, as it is enchantingly When approaching the area during pick-up you might be called, is a system for parents who don’t want to come excused from thinking that you’ve alighted at the opposite into school and hang around until the official start time of end of the Eurostar. With such an enormous student body, 8:30am. “Any learning difficulties are identified quickly,” parents’ reports are mixed. Some parents insist the kids said the head. The school sets high standards for reading “don’t get lost, are well looked after,” while others said that and writing, and tracks development and progress in-house once in college “students are a number and their teachers with a reading test as well as SEN assessment. Sport has hardly know them.” also been taken up a notch since the school has grown. -

2014 Admissions Cycle

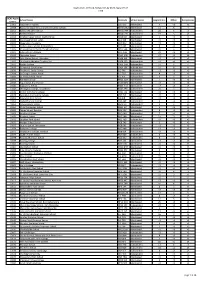

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

GIPSY HILL SECONDARY ACADEMY Completing and Submitting Your Application

Free school application form 2015 Mainstream and 16 to 19 (updated February 2015) GIPSY HILL SECONDARY ACADEMY Completing and submitting your application Before completing your application, please ensure that you have read both the relevant ‘How to Apply’ guidance and the assessment criteria booklet carefully. These can be found here. Please also ensure that you can provide all the information and documentation required. The free school application is made up of nine sections . Section A: Applicant details and declaration . Section B: Outline of the school . Section C: Education vision . Section D: Education plan . Section E: Evidence of need . Section F: Capacity and capability . Section G: Budget planning and affordability . Section H: Premises . Section I: Due diligence and other checks In Sections A and B we are asking you to tell us about your group and provide an outline of the school. This requires the completion of the relevant sections of the Excel application form. In Sections C to F we are asking for more detailed information about the school you want to establish and the supporting rationale. This requires the completion of the relevant sections of the Word application form. In Section G we are asking specifically about costs, financial viability and financial resilience. This requires the completion of the relevant sections of the Excel budget template and Word application form. In Section H we are asking for information about premises, including information about suitable site(s) you have identified. This requires the completion of the relevant section of the Excel application form. Section I is about your suitability to set up and then run a free school. -

20Th November 2015 Dear Request for Information Under the Freedom

Governance & Legal Room 2.33 Services Franklin Wilkins Building 150 Stamford Street Information Management London and Compliance SE1 9NH Tel: 020 7848 7816 Email: [email protected] By email only to: 20th November 2015 Dear Request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (“the Act”) Further to your recent request for information held by King’s College London, I am writing to confirm that the requested information is held by the university. Some of the requested is being withheld in accordance with section 40 of the Act – Personal Information. Your request We received your information request on 26th October 2015 and have treated it as a request for information made under section 1(1) of the Act. You requested the following information. “Would it be possible for you provide me with a list of the schools that the 2015 intake of first year undergraduate students attended directly before joining the Kings College London? Ideally I would like this information as a csv, .xls or similar file. The information I require is: Column 1) the name of the school (plus any code that you use as a unique identifier) Column 2) the country where the school is located (ideally using the ISO 3166-1 country code) Column 3) the post code of the school (to help distinguish schools with similar names) Column 4) the total number of new students that joined Kings College in 2015 from the school. Please note: I only want the name of the school. This request for information does not include any data covered by the Data Protection Act 1998.” Our response Please see the attached spreadsheet which contains the information you have requested. -

Hints and Tips for Applying to a Secondary School for Entry in September 2018

Hints and tips for applying to a secondary school For entry in September 2018 www.rbkc.gov.uk/schools/admissions Apply online: www.rbkc.gov.uk / schools/admissions The Pan-London eAdmissions site opens on 1 September 2017. If your child was born between 1 September 2006 and 31 August 2007, you will need to apply for a secondary school place by 31 October 2017. Information from this Admissions Team document can be made Green Zone, 2nd Floor available in alternative formats Town Hall, Hornton Street W8 7NX and in different languages. 020 7745 6432 If you require further assistance Email: [email protected] or more information, please use www.rbkc.gov.uk/schools/admissions the contact details opposite. The benefits of applying online l It is quick and easy to do. l You are able to attach additional documents. l The opportunity to apply from any location with internet access l During the evening of 1 March 24 hours a day, seven days a 2018, you will be sent an email week up until the closing date, informing you that your outcome 31 October 2017. is available. l You can log back on to change l Once you have received this email, or delete preferences up until you can log onto the Pan-London 11.59pm on the closing date. eAdmissions website to accept or decline your offer. l You can register your mobile phone number to receive reminder alerts. If you would prefer to complete a paper application form, please l You will automatically receive contact the Admissions Team. -

ROYAL BOROUGH of KENSINGTON and CHELSEA Family and Children's Services FAIR ACCESS PROTOCOL Background 1. the School Admission

ROYAL BOROUGH OF KENSINGTON AND CHELSEA Family and Children’s Services FAIR ACCESS PROTOCOL Background 1. The School Admissions Code 3.44 (statutory from 10 February 2009), imposes a mandatory duty on Local Authorities to have a Fair Access Protocol in place which ensures that access to education is secured quickly for children1 who have no school place and that all schools in an area admit their fair share of the most vulnerable children, including those with challenging behaviour. All schools and academies must2 agree and participate in the Fair Access Protocol and will be expected to admit children above their published admissions number if the school is already full. 1.2 The introduction of statutory In-Year Coordination of Admissions from September 2010 will improve the mechanisms for LAs in identifying children out of school and children who may require a school placement in accordance with the Fair Access Protocol. The Royal Borough Admissions Team will be the first point of contact for parents/carers resident in the Royal Borough seeking a school place for their child. In the majority of cases, children will be allocated a school place in accordance with normal in-year admission procedures in a Royal Borough school, or more often - due to geography and the local context (para. 3.3) - a neighbouring borough school. 1.3 In accordance with 3.47 of the Code, the Royal Borough’s Admissions Forum must monitor the effectiveness of the Fair Access Protocol and consider how well existing and proposed admissions arrangements meet the interests of children and parents/carers resident in the Royal Borough. -

Annual Report 2020

Holland Park School Consolidated Annual Report and Financial Statements Year to 31 August 2020 Company Limited by Guarantee Registration Number 8588099 (England and Wales) Contents Reports Reference and administrative information 1 Governors’ report 3 Governance statement 17 Statement of regularity, propriety and compliance 23 Statement of governors’ responsibilities 24 Independent auditor’s report on the financial statements 25 Independent accountant’s report on regularity 29 Financial statements Consolidated statement of financial activities 31 Balance sheets 32 Consolidated statement of cash flows 33 Principal accounting policies 35 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 41 Holland Park School Reference and administrative information Members Miss Margaret Allen Ms Anne Marie Carrie Professor Peter McCaffery Mrs Elizabeth Rutherford JP Dr Krish Soni Mr Michael Tory Governors Miss Margaret Allen Mrs Sally Bercow Ms Catherine Blackler* Ms Anne Marie Carrie (Chair) Mr David Chappell (Academy Head & Accounting Officer)* Mr Yasser el Gabry* Mr Colin Hall (Head) Professor Peter McCaffery Mrs Elizabeth Rutherford JP (Vice Chair) Dr Krish Soni* Mr Michael Tory *Members of the Resources & Audit Committee Clerk to the Governors Mrs Lyn Stanton Company Secretary Wilsons Solicitors LLP Leadership Team 2019 - 2020 Head Colin Hall Academy Head David Chappell (Accounting Officer) Associate Head Nicholas Robson Deputy Heads Ross Wilson Faye Mulholland Robert Orr Joseph Holloway Assistant Headteachers Simon Dobson Benjamin Arnold Chief Finance -

Pathways to Success

London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham | Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea Westminster City Council Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. APPLYING TO 6TH FORM OR COLLEGE ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. APPLYING FOR AN APPRENTICESHIP OR TRAINEESHIP .................................................................................................................................. 4 3. EMPLOYMENT WITH PART-TIME EDUCATION OR TRAINING .......................................................................................................................... 5 4. SUPPORTED INTERNSHIP FOR YOUNG PEOPLE WITH SEND .......................................................................................................................... 5 5. LINKS TO 14-19 WEBSITES .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 5.1. LONDON BOROUGH OF HAMMERSMITH AND FULHAM .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 5.2. ROYAL BOROUGH OF KENSINGTON AND CHELSEA.............................................................................................................................................................. -

Holland Park School

School report Holland Park School Airlie Gardens, Campden Hill Road, London, W8 7AF Inspection dates 12–13 November 2014 Previous inspection: Not previously inspected as an academy Overall effectiveness This inspection: Outstanding 1 Leadership and management Outstanding 1 Behaviour and safety of pupils Outstanding 1 Quality of teaching Outstanding 1 Achievement of pupils Outstanding 1 Sixth form provision Outstanding 1 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is an outstanding school. Students, staff and parents are immensely proud The headteacher is an inspiration to all. His to be part of this exceptional academy. relentless drive for improvement touches every Students make outstanding progress in a wide single aspect of this wonderful learning community. range of subjects and in all year groups. Leaders and teachers embrace the academy’s Students’ behaviour is exemplary. Their superb commitment to scholastic excellence with vigour. attitudes to learning permeate all lessons and play Their determination to challenge each other and all a key part in their outstanding progress. They feel students pervades the entire community. utterly safe and nurtured. The academy shows Governors are proud to lead the academy. They are excellent practice in the way it safeguards and unwavering in their commitment to its continued promotes their well-being. improvement. They are focused, skilled and Students’ desire for education has no bounds. assertive in their support and challenge for the They soak up enrichment with relish and seek academy. broader learning at every opportunity. They are A strong moral and spiritual purpose permeates the confident, curious and always compassionate. academy. Students are excited by the huge range Teaching is outstanding and often exceptional. -

Wood Lane and Notting Hill Gate

1 Appendix A Page number Questionnaire 2 Letters distributed in each 6 neighbourhood Letter distribution maps 16 Consultation leaflets 19 Emails to people who use public transport or cycle in the areas affected by 24 our proposals Stakeholder email 28 List of stakeholders invited to respond to 29 the consultation Press Release 35 Press advertisement 41 Digital advertisement 42 2 Questionnaire 1a. Thinking about our proposals as a whole, what effect do you think they will have on the way people choose to travel? A limited Many number more of extra I am unsure The Fewer people people people what effect proposals would choose would would the would have to travel in choose to choose proposals no effect this way travel in to travel might have this way in this way Walking Cycling Using public transport Using motor vehicles for personal journeys Using motor vehicles for business journeys It would help us if you could use the space below to explain your answers to the question above. If you are commenting on a particular location, please mention it to help us analyse the responses: 2, Which neighbourhoods do your views relate to, or are you commenting on the entire scheme? If you wish to comment on more than one section (but not the entire route) then you may find it easier to write to us at [email protected] or Freepost TfL Consultations (Wood Lane to Notting Hill Gate). Wood Lane Shepherd’s Bush Holland Park Avenue Notting Hill Gate The entire scheme 3 3. Please let us know if the proposals would have a positive or negative impact on you or the journeys you make.