A Qualitative Investigation of Diverse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 6 Fine Arts

Sixth Grade Fine Arts Activities Dear Parents and Students, In this packet you will find various activities to keep a child engaged with the fine arts. Please explore these materials then imagine and create away! Inside you will find: Tiny Gallery of Gratitude… Draw a picture relating to each prompt. Facial Expressions- Practice drawing different facial expressions. Proportions of the Face- Use this resource to draw a face with proper proportions. Draw a self-portrait- Use your knowledge from the proportions of the face sheet to create a self-portrait. Sneaker- Design your own sneaker. How to Draw a Daffodil- See if you can follow these steps to draw a daffodil. Insects in a Line- Follow the instructions to draw some exciting insects! Let’s Draw a Robot- Use these robot sheets to create your own detailed robot. Robot Coloring Sheet- Have fun. 100 Silly Drawing Prompts- Read (or have a parent or sibling read) these silly phrases and you try to draw them. Giggle and have fun! Musician Biographies- Take some time to learn about a few musicians and reflect on their lives and contributions to popular music. Louis Armstrong Facts EARLY LIFE ★ According to his baptismal records, Louis Armstrong was born in New Orleans, Louisiana on August 4, 1901, although for many years he claimed to have been born on July 4, 1900. ★ His mother, Mary Albert, was only sixteen when she gave birth to Louis; his father, William Armstrong, abandoned the family shortly after his birth - this resulted in Louis being raised by his grandmother until he was about five years old, when he returned to his mother’s care. -

Glitter the Deadline for Voting in the 2012 Fan Activity Achievement Awards (Faan Awards) Is March 9, 2012

1 FAAn Awards Deadline Is Today! Corflu Glitter The deadline for voting in the 2012 Fan Activity Achievement Awards (FAAn Awards) is March 9, 2012. That’s today, but there’s still (Corflu 29) time to get your choices for the best writers, artists, editors and posters of 2011. Voting is free, all knowledgeable fans are eligible to cast a ballot Sunset Station and it’s the fannish thing to do. The top finishers in each category and the Number One Fan Face (highest overall point getter) will receive Hotel-Casino awards at the Corflu Glitter banquet. All top finishers will be featured in a special results fanzine written Henderson, NV by Arnie Katz, Andy Hooper, Claire Brialey and other well-known fans. Volunteer writers are most welcome. If you’d like to help, write to Ar- nie ([email protected]). April 20-22, 2012 Full Website Poised to Go! The upgraded Corflu website ( www.Corflu.org ) is about to go live. Email: [email protected] This will replace the temporary site put up by Bill Burns. “The combined talent and energy of Corflu Web Host Bill Burns and Corflu Webmaster Tom Becker has finally triumphed over the sloth and Glitter #53, March 9, 2012 , The procrastination of the site’s head writer,” notes Arnie Katz, the head Glish, is the fanzine of Corflu Glit- writer. “A little polite whip-cracking has pried the needed content from ter, the 29th edition of what has the writer so that Tom and Bill can put the full site into place in the next become the World Trufandom few days.” Convention. -

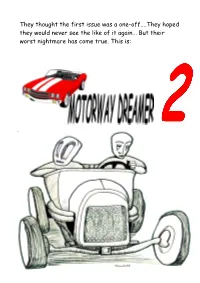

They Thought the First Issue Was a One-Off...They Hoped They Would

They thought the first issue was a one-off....They hoped they would never see the like of it again... But their worst nightmare has come true. This is: Motorway Dreamer is “edited” and published by John Nielsen Hall. Please direct all contributions, Letters of Comment, obscene suggestions, Statements of Claim, details of salacious fantasies etc. to: Coachmans Cottage, Marridge Hill Ramsbury, Wilts. SN8 2HG U.K. E-mail: [email protected] In This Issue: Bruce Townley Graham Charnock Ted White Even MORE obligatory poetry Art Credits: Bruce Townley ( cover), Harry Bell(Pages 5 + 14), Traditional Thangka Art- Tibetan – A Wrathful Vajrapani ( Page 8)Unknown( Good innit?)(Page 13) and clip art (Pages 10+11). THINGS YET TO COME The depressing rain fell heavily on the isolated cottage, the dark clouds galloped overhead driven by a relentless wind. At one of the upstairs windows, the pale glow of lights and computers would have been noticeable from the outside, if there had been anyone to notice. But there was no one. There wasn’t another living soul for many miles. Only on the inside was there human activity, represented by a frown of concentration, or an occasional twitch of the lips that may have been amusement, as an otherwise still figure hunched over a keyboard, hands and forearms encased in steel and rubber gloves, eyes fixed on the glowing screen. The figure was old – very old now. But the legend across the top of the frame of the window that held his work bore testimony to his industry. MOTORWAY DREAMER it read. -

A Study to Identify the Need for Videotaped Training Material for Civilian Clubs Terry Clark Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-1983 A study to identify the need for videotaped training material for civilian clubs Terry Clark Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14060846 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Hospitality Administration and Management Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Terry, "A study to identify the need for videotaped training material for civilian clubs" (1983). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2372. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2372 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY TO IDENTIFY THE NEED FOR VIDEOTAPED TRAINING MATERIAL FOR CIVILIAN CLUBS by TERRY CLARK A hospitality project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in HOTEL AND FOOD SERVICE MANAGEMENT at FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Committee in charge: Professor Ted White Doctor Donald Greenaway April 1983 To Doctor Donald Greenaway and Professor Ted White This hospitality project, having been approved in respect to form and mechanical execution, is referred to you for judgment upon its substantial merit. Dean Anthony G. Marshall School of Hospitality Management The hospitality project of Terry Clark is approvedo Professor Ted White Doctor Donald Greenaway Date of Review: ABSTRACT A STUDY TO IDENTIFY THE NEED FOR VIDEOTAPED TRAINING MATERIAL FOR CIVILIAN CLUBS by Terry Clark The purpose of this study is to determine if there is a need and a market for the production of video-taped employee training films specifically geared to subjects unique to club management. -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

Pixelthirteen View of Ahead

M a y 2 0 0 7 } Straight down does not give one a great PIXELThirteen view of ahead. ~ Edited and published monthly by David Burton 5227 Emma Drive, Lawrence IN 46236-2742 Contents E-mail: [email protected] (new address – please note!) Distributed in a PDF version only. Cover: A Blue Crescent Moon from Space Available for downloading at efanzines.com thanks to Bill Burns. Expedition 13 Crew, A Noah Count Press Publication. International Space Station, NASA Compilation copyright © 2007 by David Burton. Copyright reverts to individual contributors on publication. 3 Notes From Byzantium AMDG column by Eric Mayer Much Nothings About Ado Editorial deadline for Pixel Fourteen: May 26, 2007. 7 column by Lee Lavell 10 Whither Fandom? column by Ted White 16 Found In Collection column by Christopher Garcia 18 Being Frank zine reviews by Peter Sullivan 20 Pixelated Lettercolumn Pixel Thirteen 2 May 2007 Notes From Byzantium E R I C M A Y E R Dreams Die Thin As we age, life’s possibilities slip away from us. female models, would have to weigh less than 130 pounds to When I turned twenty I realized I would never become a fall short of the threshold. To get to that point, even a natural teenage science fiction pro like Isaac Asimov. When I took up run- waif would likely have to skip meals, exercise too much, or use ning at forty and labored to finish a mile in under eight minutes I diet aids. guessed I had long since missed my chance to be the second com- I hate to disagree with the experts but I’ve met the height and ing of Roger Bannister. -

Aretha Franklin Greatest Hits Mp3, Flac, Wma

Aretha Franklin Greatest Hits mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Funk / Soul Album: Greatest Hits Country: Europe Released: 2009 Style: Soul-Jazz, Soul MP3 version RAR size: 1386 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1231 mb WMA version RAR size: 1118 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 585 Other Formats: AIFF MMF AHX ADX MOD MIDI MPC Tracklist Hide Credits –Aretha Franklin With George I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me) A1 4:02 Michael Written-By – Dennis Morgan, Simon Climie Respect A2 –Aretha Franklin 2:25 Written-By – Otis Redding I Say A Little Prayer A3 –Aretha Franklin 3:34 Written-By – Burt Bacharach/Hal David* Think A4 –Aretha Franklin 2:17 Written-By – Aretha Franklin, Ted White (You Make Me Feel) Like A Natural Woman A5 –Aretha Franklin 2:46 Written-By – Gerry Goffin/Carole King*, Jerry Wexler I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Loved You) A6 –Aretha Franklin 2:51 Written-By – Ronnie Shannon You Are All I Need To Get By A7 –Aretha Franklin 3:36 Written-By – Nickolas Ashford/Valerie Simpson* Chain Of Fools A8 –Aretha Franklin 2:48 Written-By – Don Covay Spanish Harlem A9 –Aretha Franklin 3:30 Written-By – Jerry Leiber, Phil Spector Angel A10 –Aretha Franklin 4:29 Written-By – Carolyn Franklin, Sonny Saunders* Let It Be A11 –Aretha Franklin 3:32 Written-By – Lennon/McCartney* Until You Come Back To Me (That's What I'm Gonna Do) B1 –Aretha Franklin Written-By – Clarence Paul, Morris Broadnax, Steve 3:26 Wonder* Son Of A Preacher Man B2 –Aretha Franklin 3:16 Written-By – John Hurley, Ronnie Wilkins Don't Play That Song (You Lied) B3 –Aretha -

Mississippi Legislature First Extraordinary Session 2018

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE FIRST EXTRAORDINARY SESSION 2018 By: Representatives Scott, To: Rules Sykes, Perkins, Banks HOUSE RESOLUTION NO. 1 1 A RESOLUTION MOURNING THE LOSS AND COMMEMORATING THE LIFE AND 2 STELLAR MUSIC CAREER OF THE IRREFUTABLE QUEEN OF SOUL AND RHYTHM 3 AND BLUES LEGEND MRS. ARETHA LOUISE FRANKLIN AND EXPRESSING 4 DEEPEST SYMPATHY TO HER FAMILY AND FRIENDS UPON HER PASSING. 5 WHEREAS, it is written in Ecclesiastes 3:1, "To everything 6 there is a season, and a time for every purpose under the Heaven," 7 and as such, the immaculate author and finisher of our soul's 8 destiny summoned the mortal presence of a dearly beloved 9 international songbird and world-renowned singer, songwriter and 10 acclaimed pianist, the irrefutable Queen of Soul and incomparable 11 rhythm and blues legend, Mrs. Aretha Louise Franklin, as she has 12 made life's final transition from earthly travailing to heavenly 13 reward, rendering great sorrow and loss to her family, friends and 14 fan base; and 15 WHEREAS, born on March 25, 1942, in Memphis, Tennessee, the 16 daughter of Mississippi Delta natives, Reverend Clarence LaVaughn 17 (C.L.) Franklin and church pianist Barbara Siggers Franklin, the 18 State of Michigan and the entirety of the world's musical and 19 entertainment industry lost a wonderful friend and icon with the H. R. No. 1 *HR31/R8* ~ OFFICIAL ~ N1/2 181E/HR31/R8 PAGE 1 (ENK\JAB) 20 passing of Mrs. Franklin on Thursday, August 16, 2018, and there 21 is now a hush in our hearts as we come together to pay our 22 respects to the memory of one who has been called to join that 23 innumerable heavenly caravan as she now enjoys the eternal peace 24 described in Luke 2:29, "Lord, now you are letting your servant 25 depart in peace, according to your word"; and 26 WHEREAS, at the tender age of five, her father, renowned 27 preacher and gospel legend, Reverend C.L. -

Television Academy Awards

Outstanding Music Supervision All American The Bigger Picture This episode examines the impact of policing on the Black community. When a young Black woman is shot by the police, after being found sleeping in her car, Olivia uses her podcast to address social justice issues and leaks the damning body-cam footage. Madonna Wade-Reed, Music Supervisor All In: The Fight For Democracy All In: The Fight For Democracy follows Stacey Abrams’s journey alongside those at the forefront of the battle against injustice. From the country’s founding to today, this film delves into the insidious issue of voter suppression - a threat to the basic rights of every American citizen. Andrew Gross, Music Supervisor Amend: The Fight For America Citizen After escaping slavery, Frederick Douglass becomes a pivotal voice calling for citizenship for Black Americans, a dream realized in the 14th Amendment. Ian Broucek, Music Supervisor Kevin Writer, Music Supervisor American Idol My Personal Idol/Artist Singles As American Idol gets closer to crowning its winner when the top five becomes the top three in the live coast-to-coast vote, songwriter, producer and artist, FINNEAS, mentors the finalists, who perform three songs, including their recently recorded winner’s single, each produced by a renowned music producer. Robin Kaye, Music Supervisor Ashley Viergever, Music Supervisor American Soul: The Untold Story Of Soul Train Say You Love Me The story of entrepreneur Don Cornelius, who developed the Soul Train show, which rose to prominence in the 1970s. Don confronts Flo about moonlight for his competition, while The Godfather of Soul puts Soul Train on pause to reclaim his poached musicians from Parliament Funkadelic. -

Freedom (Stands For) Freedom (Oh) Freedom (Yeah) Freedom!

(Cause) Freedom (Stands For) Freedom (Oh) Freedom (Yeah) Freedom! It’s one word, really, repeated four times with interjections, echoed by a choir of women. But oh, how Aretha Franklin sang the bejesus out of the bridge to her 1968 hit “Think.” She built the stairway to the song’s climactic crescendo step-by-step. The first “freedom” is a statement, a tonic note, posed. The Queen of Soul takes the delivery up a notch on the second “freedom,” raising the scale and the stakes. She pitches a half step up on the third line, holding the note perilously, like a proposition or a promise. And then she lets that great big voice of hers loose, returning to the tonic but lifted an octave higher. That fourth “freedom” is a shout, a declaration, a testimonial, an exaltation. It’s everything that needs to be said, the word made an exclamation point in a way that only a woman born into the church and nursed by gospel could deliver it. “FREEDOM!” And then she repeats the whole thing one more time, for good measure. Contextually, this proclamation is a bit of a non sequitur — an abstract step away from the command tense of the rest of the song, in which Franklin tells her man what he needs to do to keep their relationship together: namely, “think.” “Think” has rightly been interpreted as one of the artist’s definitive feminist anthems. Ironically, her husband and manager Ted White, whom she later accused of abuse, is credited as a co-writer, but the singer’s sister Carolyn has said the song was all hers. -

“Respect”--Aretha Franklin (1967) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Meredith Ochs (Guest Post)*

“Respect”--Aretha Franklin (1967) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Meredith Ochs (guest post)* Aretha Franklin When she fell in love with Otis Redding’s “Respect,” Aretha Franklin didn’t know that her version would become one of the most important recordings of the 20th century. She wasn’t thinking about its place in the vortex of social movements--Civil Rights, women’s equality, Black Power. To her, it was a mainly relationship song, the opening track of a collection of relationship songs: “I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You,” her tenth album, and her Atlantic Records debut. There’s no question that “Respect” (which made it into the first class of the National Recording Registry in 2002) became a universal anthem for anyone or any group fighting for recognition, for equality, for justice. “But when I recorded it, it was pretty much a male-female kind of thing,” Aretha said. It was, however, “the right song at the right time,” she said. And she was the right medium. Aretha grew up singing in the Baptist church, raised by one of its most prominent leaders, the Reverend C.L. Franklin. The living room of their Detroit, Michigan, home was a revolving door of artists and activists deeply involved in Civil Rights. Among them was Martin Luther King, Jr., who road-tested his “I Have a Dream” speech alongside Reverend Franklin at Detroit’s 1963 Walk to Freedom two months before King gave its definitive version in Washington, DC. From a very early age, Aretha absorbed the notion that respect was not only a core principal of the Civil Rights movement--it was at her core as well. -

Farewell, Dr. Gafia

Farewell, Dr. Gafia 1 Good-Bye rich ::: Arnie Katz ::: 3 The Obituary ::: Dan Joy ::: 5 rich brown ::: Ted White ::: 6 rich brown and the Coffee Table Book ::: Dan Steffan ::: 8 It Started with a LoC ::: Linda Blanchard ::: 11 I Remember rich ::: Joyce Katz ::: 12 Recalling rich ::: Roxanne Mills ::: 15 In Capital Letters ::: Mike McInerney ::: 16 The Best Man ::: Steve Stiles ::: 18 Dr. Gafia’s Dictionary ::: Peter Sullivan ::: 20 My Friend rich ::: Shelby Vick ::: 21 Farewell to a Fan ::: Jack Calvert ::: 22 Golden Halls of Mirth ::: rich brown & Paul Stanberry ::: 24 2 Rich brown was an unshakably loyal friend, came friends almost immediately. an exemplary human being and one of the best Rich shepherded me through that meeting, pled damn fans of his era. He touched many lives, in- my case for admission with the other Fanoclasts variably for the good, including mine. and quickly took over my fannish education. He Rich wasn’t the first fan I met and, even at the told me anecdotes based on his personal experi- time, not the biggest BNF who had deigned to ac- ences and his knowledge of fanhistory, explained knowledge my existence. Yet from the moment I things I didn’t understand, and shared insights that met him, he exercised a powerful, positive influ- were well beyond my powers of perception at that ence on me as a human, a writer and a fan. time. Without taking away from the many others Rich and Mike were co-hosting FISTFA on who have taught me and helped me and nurtured alternate Fridays to Fanoclasts meetings.