Schutzhund and IPO Jim Engel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18 - Poodle Club of America, Inc

PERFORMANCE SWEEPSTAKES FOR POODLE CLUB OF AMERICA, INC. Rules and Procedures The Performance Sweepstakes is a Performance Event and is intended to be not only a competition, but more importantly a learning experience for those who enter and compete. With that in mind, the Performance Sweepstakes event will be run under the following rules and procedures. Eligibility: Any Poodle registered with the American Kennel Club (including those with Limited Registration) may compete as long as they have earned a title or certificate prior to the close of entries in one of the following disciplines: AKC Obedience, Rally, Agility, Coursing Ability, Fast CAT, Tracking, Barn Hunt, Dock Diving, Farm Dog, Retriever Hunt Tests, Spaniel Hunt Tests, Canine Good Citizen, Flyball, Therapy Dog, Trick Dog and Search and Rescue. Or have earned one of the following PCA certificates: PCA Working Certificate, Working Certificate Excellent, Upland Instinct Certificate, Upland Working Certificate, Upland Working Certificate Excellent (also includes Hunting Poodle and Hunting Poodle Excellent titles). Spayed and neutered dogs and bitches are eligible to participate and will be judged together with intact dogs and bitches. Honorable scars and injuries are to be expected with working dogs and are to be judged accordingly. Any trim is acceptable other than fancy grooming competition type trims. No attachments to the hair are allowed other than rubber bands as permitted in the Poodle breed standard. Classes: There will be 6 classes, split by age and sex: Junior Dog and Junior Bitch, for dogs 6 months and under 2 years Open Dog and Open Bitch, for dogs 2 years and under 7 years Senior Dog and Senior Bitch, for dogs 7 years and over All size Poodles will be shown together, to be judged against the breed standard with the dog's height being immaterial in the judging. -

Leerburg Dominant Dog Collar™ Leather Slip Collar

LEERBURG FOR ALL DOGS Your Puppy 8 Weeks to 8 Months How to Raise a Working Puppy 1 Hour, 59 Minutes | leerburg.com/120.htm 1 Hour, 15 Minutes | leerburg.com/117.htm DVD | #120-D $40.00 DVD | #117-D $40.00 Ed Frawley & Cindy Rhodes Video on Demand | #S120 $30.00 Video on Demand | #S117 $30.00 This is not a bite training video. It is a video teaching Over the years, this DVD has been one of our most 780 free streaming videos---all of which are available on Leerburg’s Video on De- people how we used to raise our pups here at popular training videos for new puppy owners. This Leerburg. This video outlines a step-by-step manner mand. The website also has a free training forum with nearly 20,000 registered training video answers all the questions new puppy members and over 380,000 posts. how to socialize, imprint, and prepare your puppy owners have concerning the care of their new pup- for his or her working career. This is a common sense Leerburg’s reputation has been built on customer service and quality products. py. This DVD was originally produced to be given to approach that anyone can do. The key to raising a From the very beginning, Ed’s philosophy on selling dog related products was to every Leerburg Puppy Customer. The intent was to successful working puppy is to have a plan and make only offer products he would use to train his personal dogs. He knew there were help Leerburg Puppy Customers get through the the best use of the time you spend with your dog. -

ARC VERSATILITY (V) and VERSATILITY EXCELLENT (VX) AWARD REQUIREMENTS Approved by ARC Board of Directors: 7/4/05

ARC VERSATILITY (V) AND VERSATILITY EXCELLENT (VX) AWARD REQUIREMENTS Approved by ARC Board of Directors: 7/4/05 The Versatility (V) and the Versatility Excellent (VX) titles are designed to spotlight the dog-handler teams who work with one another in a wide variety of events. They are awarded in recognition of the accomplishments of the dog in a wide range of activities: conformation, obedience, Schutzhund, agility, herding, and other activities in which certification is earned. Versatility (V) Award The Versatility (V) title is awarded to dogs whose achievements have been recognized in at least three (3) conformation and/or performance event categories (A through G). Dogs receiving the Versatility (V) title must have completed at least a CD or a BH and must have attained an advanced degree in obedience (CDX), Schutzhund (SchH I), tracking (VST or TDX), agility (OA), herding (HI), or carting (CX). (An advanced degree in Rally does not meet this requirement.) 1. A minimum of 13 versatility points must be earned. 2. The dog must have completed a CD or a BH. 3. At least 5 of the required points must come from a single working category (obedience, Schutzhund, tracking, agility, herding, carting), not a combination of working categories. (Rally points do not count toward this requirement.) 4. Points must be earned in no less than three (3) of the Categories A through G (Rally points do not count toward this requirement.) 5. No more than 3 points may come from Category I: Miscellaneous. Versatility Excellent (VX) Award The Versatility Excellent (VX) title is awarded to dogs by demonstrating the ability to perform at the highest levels by accumulating at least 9 points in a single working category (obedience, Schutzhund, tracking, agility, herding). -

Two Rivers Agility Club of Sacramento Tracking Dog

JUDGES TWO RIVERS AGILITY CLUB OF SACRAMENTO Kaye Hall, #6018 TRACKING DOG TEST 4516 Dry Creek Rd, Napa CA 94558 AKC Licensed Event 2021584205 Meg Azevedo #90144 [EMERGENCY JUDGE CHANGE AS OF 2/6/21) 8228 Woods Edge Ln, Elk Grove CA 95758 Julia Priest #92184 24313 Kennefick Rd, Galt CA 95632 TEST SECRETARY Karey Krauter 374 Stanford Ave, Palo Alto CA 94306 [email protected], 650-906-5146 TEST CHAIR Sharon Prassa CHIEF TRACKLAYER Sue Larson SUNDAY, February 21, 2021 TRACKING TEST COMMITTEE MATHER REGIONAL PARK Karey Krauter, Sue Larson, Sharon Prassa, Cathy Beam, RANCHO CORDOVA, CALIFORNIA All Officers and Directors of the Association ENTRIES LIMITED TO: 6 DOGS CLUB OFFICERS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Dogs registered in the AKC Canine Partners Program are accepted at this test. President: Kathie Leggett Vice-President Roger Ly Debby Thompson Treasurer Sandra Zajkowski Penny Larson ENTRIES CLOSE: Secretary Becky Hardenbergh Karen O’Neil 6:00 PM, Thursday, February 11, 2021 8027 Grinzing Way, Sacramento, CA 95829 Agility Coordinator: Tracking Coordinator: Entry fee: $60.00 Rosalie Ball Karey Krauter (Includes $0.50 AKC recording fee and $3.00 event fee) Draw for Entry: 6:15 PM, Thursday, February 11, 2021 VETERINARIANS ON CALL Starbucks, 2000 El Camino Real, Palo Alto CA 94306 Sacramento Animal Medical Group, (916) 331‐7430 TRACS is participating in the ‘AKC Rule: Chapter 1, Section 17d Test Worker Option.’ 4990 Manzanita Ave, Carmichael CA 95608 TRACS is setting aside 1 track in this test for workers that qualify for this draw. VCA Sacramento Veterinary Referral Center, (916) 362‐3111 American Kennel Club Certification 9801 Old Winery Place, Rancho Cordova CA Permission has been granted by the American Kennel Club for the holding of this event under the American Kennel Club IN CASE OF HUMAN EMERGENCY, DIAL 9-1-1 Rules and Regulations. -

Sled Dogs in Our Environment| Possibilities and Implications | a Socio-Ecological Study

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1996 Sled dogs in our environment| Possibilities and implications | a socio-ecological study Arna Dan Isacsson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Isacsson, Arna Dan, "Sled dogs in our environment| Possibilities and implications | a socio-ecological study" (1996). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3581. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3581 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I i s Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University ofIVIONTANA. Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** / Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Date 13 ^ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. SLED DOGS IN OUR ENVIRONMENT Possibilities and Implications A Socio-ecological Study by Ama Dan Isacsson Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Studies The University of Montana 1996 A pproved by: Chairperson Dean, Graduate School (2 - n-çç Date UMI Number: EP35506 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

The Cocker Spaniel Schutzhund Training Walking Down the Aisle

E E R F June 2006 | Volume 3 Issue 6 The Cocker Spaniel Schutzhund Training Walking Down the Aisle with Fido Debunking Common Canine Myths Protecting Family Pets During Domestic Abuse In-FFocus Photography We have a name for people who treat their dogs like children. Customer. There are people who give their dogs commands and those who give them back rubs. There are dogs who are told to stay off the couch and those with a chair at the table. And there are some who believe a dog is a companion and others who call him family. If you see yourself at the end of these lists, you’re not alone. And neither is your dog. We’re Central Visit centralbarkusa.com Bark Doggy Day Care, and we’re as crazy about for the location nearest you. your dog as you are. Franchise opportunities now available. P u b l i s h e r ’ s L e t t e r If your dog is 13 years old (in humane years), is he really 91 years old in dog years? Is the grass your dog eating merely for taste or is it his form of Pepto-Bismol®? When Fido cow- ers behind the couch, does he really know why you're unhappy? There are dozens of myths, or in other words, legends that we as dog lovers either want to believe or simply can't deny. Yet at the end of the day, they are still myths. Flip over to page 18 as we debunk some of the most popular myths found in the canine world. -

GREENSPRING POODLE CLUB, INC. (Unbenched-Indoors) (Licensed by the American Kennel Club)

#2020034303 (Saturday AM) #2020034304 (Saturday PM) #2020034305 (Sunday AM) #2020034306 (Sunday PM) ENTRIES CLOSE: 12:00 NOON, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2020 or when the numerical limit is reached AT SHOW SECRETARY'S OFFICE After Which Time Entries Cannot Be Accepted, Cancelled or Substituted EXCEPT as Provided for in Chapter 11, Section 6 of the Dog Show Rules. EACH SHOW IS LIMITED TO 100 ENTRIES. **ENTRIES OPEN 9:00 AM, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2020** Entries will not be taken prior to the date and time listed above. PREMIUM LIST GREENSPRING POODLE CLUB, INC. (Unbenched-Indoors) (Licensed by the American Kennel Club) Frederick Fairgrounds Building 14A 797 East Patrick St Frederick, MD 21705 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2020 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2020 SHOW HOURS: 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM Cullen Leck, Show Secretary c/o Rau Dog Shows, Ltd. P. O. Box 6898 Reading, PA 19610 1 Accommodations Please contact the individual hotel on pet policy – some restrictions may apply and a pet deposit may be required. Dogs should not be left in rooms unsupervised, We appreciate your cooperation in assuring that the hotel rooms and grounds are left in neat condition. Hampton Inn 5311 Buckeystown Pike, Frederick MD . 301-698-2500 Clarion Inn 5400 Holiday Drive, Frederick MD . 301-694-7500 Mainstay Suites 7310 Executive Way, Frederick MD . 301-668-4600 Days Inn Leesburg 721 E. Market Street, Leesburg VA . 703-777-6622 Comfort Inn 7300 Executive Way, Frederick, MD . 301-688-7272 Motel 6 999 W Patrick St, Frederick MD . 301-662-5141 Travelodge 620 Souder Road, Brunswick, MD 21716 Directions Baltimore & East, NE Take I-70 West to East Patrick Street, exit #56. -

Printable Dog Resource List

1 Dog Related Websites and Recommended Resources from A to Z Prepared by Dana Palmer, Sr. Extension Associate Department of Animal Science, Cornell University www.ansci.cornell.edu for March Dog Madness, March 17, 2018 No endorsement is intended nor implied by listing websites here. They are grouped by topic and compiled for your information. All links were functional as of March, 2018 using Firefox. The intent is to share resources related to Dogs. A Subject: Agility Did you know the sport of Dog Agility originated in England in 1977? Affordable Agility is a company that has been known to help local 4-H clubs in New York. Visit their website here www.affordableagility.com or contact them at P.O. Box 237 Bloomfield, NY 14469. 585-229- 4936. You’ll find reasonably priced equipment, including portable teeters! Business Owner, Pamela Spock, was a guest speaker at March Dog Madness 2004. Another private business, which sells inexpensive agility equipment, Agility of Course, is located at 458 Blakesley-Nurse Hollow Road, Afton, NY 13730. This company supplies equipment for large scale events. For more information see: www.max200.com or phone 1-800-446-2920, 2113 State Rt. 31, Port Byron, NY 13140. They are in the business to travel and rent whole courses for trials and an invited guest at March Dog Madness 2016. JFF (Just For Fun) agility equipment is whatever works. This website gives you tips for creating equipment using everyday objects. You will also find web links for Herd Dog Training. http://www.dog-play.com/agility/agilitye.html Diane Blackman is the Dog-Play Webmaster. -

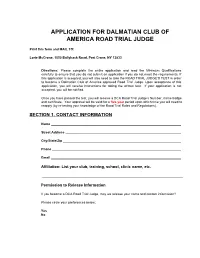

Road Trial Judge Application

APPLICATION FOR DALMATIAN CLUB OF AMERICA ROAD TRIAL JUDGE Print this form and MAIL TO: Lorie McCrone, 1050 Ballyhack Road, Port Crane, NY 13833 Directions: Please complete the entire application and read the Minimum Qualifications carefully to ensure that you do not submit an application if you do not meet the requirements. If this application is accepted, you will also need to take the ROAD TRIAL JUDGE’S TEST in order to become a Dalmatian Club of America approved Road Trial Judge. Upon acceptance of this application, you will receive instructions for taking the written test. If your application is not accepted, you will be notified. Once you have passed the test, you will receive a DCA Road Trial Judge’s Number, name badge and certificate. Your approval will be valid for a five-year period upon which time you will need to reapply (by re-testing your knowledge of the Road Trial Rules and Regulations). SECTION 1. CONTACT INFORMATION Name Street Address City/State/Zip Phone Email Affiliation: List your club, training, school, clinic name, etc. Permission to Release Information If you become a DCA Road Trial Judge, may we release your name and contact information? Please circle your preferences below: Yes No SECTION 2. MINIMUM QUALIFICATIONS Mounted and/or Course Judge. The following minimum qualifications must be met to become a DCA Road Trial Judge: 1) You must be an experienced equestrian. Do you own your own horse? Yes No OR Do you regularly ride at a stable or frequently rent and/or lease a horse? Yes No 2) You (personally) must have earned (as the designated handler) an AKC Performance title on a dog. -

Two Rivers Agility Club of Sacramento Tracking Dog

JUDGES TWO RIVERS AGILITY CLUB OF SACRAMENTO Meg Azevedo (#90144), 8228 Woods Edge Ln, Elk Grove CA 95758 Mr. Robert Rollins (#4553), 909 Los Robles St, Davis CA 95618 TRACKING DOG URBAN TEST 2020 CLUB OFFICERS AKC Licensed Event 2020584214 President: Kathie Leggett Vice-President Roger Ly Treasurer Sandra Zajkowski Secretary Becky Hardenbergh 8027 Grinzing Way, Sacramento, CA 95829 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Karen O’Neil, Penny Larson, Georgia Demetre Katrina Parkinson - Agility Coordinator Karey Krauter - Tracking Coordinator TEST SECRETARY Karey Krauter, [email protected], 650-906-5146 374 Stanford Ave, Palo Alto, CA 94306 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2019 TEST COMMITTEE Royana Palmer - Chair TRACS officers and board of directors ELK GROVE REGIONAL PARK, 9950 ELK GROVE-FLORIN RD, ELK GROVE CA 95823 CHIEF TRACKLAYER Colton Meyer ENTRIES LIMITED TO: 5 DOGS Dogs registered in the AKC Canine Partners Program are accepted at this test. Veterinarian on Call (916) 685-2494 VCA Bradshaw Animal Hospital ENTRIES CLOSE: 9609 Bradshaw Road, Elk Grove, CA, 95624 6:00 PM, Thursday, December 3, 2020 In Case of Human Emergency: Call 9-1-1 Entry fee: $75.00 (Includes $.50 AKC recording fee and $3.00 event fee) This club does not agree to arbitrate claims as set forth on the Official AKC entry Draw for Entry: form for this event. 6:15 PM, Thursday, December 3, 2020 outside Starbucks, 2000 El Camino Real, Palo Alto CA 94306 Exhibitors should follow their veterinarian’s recommendation to assure their TRACS is participating in the ‘AKC Rule: Chapter 1, Section 17d Test Worker Option.’ TRACS is setting aside 1 track in this test for workers that qualify for this draw. -

Dogsport Magazine

AUTUMN 2019 WGSDCA Dogsport Magazine WINTER WORKING GERMAN SHEPHERD AND DOGSPORT CLUBS OF AUSTRALASIA WGSDCA Contents WGSDCA Editor 2 A Word from the President 3 Editor Interview with Glynis Hendricks 8 from the desk WGSDCA Constitutional Changes 14 KARYN WORTH WGSDCA 17th IGP National Championship 17 Get ready to settle down for some great reading The Infamous BAN ... Political Expediency or in our winter edition of the WGSDCA’s Dogsport Genuine Concern 22 Magazine! In this issue we have a great article on an interview with one of our members who moved all the way from South Africa to Australia with her 10 German Shepherds and 1 cat. The interview talks about her love of animals and in-particular the GSD and her Dogsport journey. June 2019, saw our organisation hold its 17th National IGP Championship, the article on the event has some great photos taken and selected for this edition by Mike Harper from Wild Dog photography. On page 14, we have outlined our recent constitutional changes which should see the Dogsport fraternity in Australia become stronger and more united. Dogsport: In this edition we return to the story on the preservation of the banning of the GSD. Special thanks to Sister Jeannie Johnston for writing such a the working dog. comprehensive article. In closing, WGSDCA wishes Sanne Pedersen the very best in Modena Italy as she represents Australia at the WUSV World Championship. Sanne won her place as Australia’s representative Mission Statement after winning the 2019 WGSDCA IGP National To maintain and improve the Championship! There is still time to donate to temperament and physical soundness of Team Australia, details and links are included in the German Shepherd dog in Australasia. -

Tracking Regulations

Tracking Regulations Amended to April 1, 2019 Published by The American Kennel Club AMERICAN KENNEL CLUB’S MISSION STATEMENT The American Kennel Club is dedicated to upholding the integrity of its Registry, promoting the sport of purebred dogs and breeding for type and function. Founded in 1884, the AKC and its affiliated organizations advocate for the purebred dog as a family companion, advance canine health and well-being, work to protect the rights of all dog owners and promote responsible dog ownership. Revisions to the Tracking Regulations Effective January 1, 2021 This insert is issued as a supplement to the Tracking Regulations amended to April 1, 2019 and approved by the AKC Board of Directors November 10, 2020 CHAPTER 1 - GENERAL REGULATIONS Section 12. Dogs that May Not Compete. No dog less than six (6) months of age may participate in tracking events. No dog belonging wholly or in part to a judge, test secretary, test chair, chief tracklayer, superintendent, or any member of such a person’s household, may be entered in any tracking test at which such person officiates or is scheduled to officiate. Nor may they handle or act as agent for any dog entered at that tracking test. If allowed by the host club, the tracking test secretary may enter dogs owned or co-owned by the secretary and may handle dogs in the tracking test. The secretary’s priority must be the handling of official secretary duties in a timely manner. If participation in the test interferes with these duties, other arrangements for handling dogs must be made.