1 Overview of Megaflooding: Earth and Mars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remote Sensing of Alpine Lake Water Environment Changes on the Tibetan Plateau and Surroundings: a Review ⇑ Chunqiao Song A, Bo Huang A,B, , Linghong Ke C, Keith S

ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 92 (2014) 26–37 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/isprsjprs Review Article Remote sensing of alpine lake water environment changes on the Tibetan Plateau and surroundings: A review ⇑ Chunqiao Song a, Bo Huang a,b, , Linghong Ke c, Keith S. Richards d a Department of Geography and Resource Management, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong b Institute of Space and Earth Information Science, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong c Department of Land Surveying and Geo-Informatics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong d Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EN, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Alpine lakes on the Tibetan Plateau (TP) are key indicators of climate change and climate variability. The Received 16 September 2013 increasing availability of remote sensing techniques with appropriate spatiotemporal resolutions, broad Received in revised form 26 February 2014 coverage and low costs allows for effective monitoring lake changes on the TP and surroundings and Accepted 3 March 2014 understanding climate change impacts, particularly in remote and inaccessible areas where there are lack Available online 26 March 2014 of in situ observations. This paper firstly introduces characteristics of Tibetan lakes, and outlines available satellite observation platforms and different remote sensing water-body extraction algorithms. Then, this Keyword: paper reviews advances in applying remote sensing methods for various lake environment monitoring, Tibetan Plateau including lake surface extent and water level, glacial lake and potential outburst floods, lake ice phenol- Lake Remote sensing ogy, geological or geomorphologic evidences of lake basins, with a focus on the trends and magnitudes of Glacial lake lake area and water-level change and their spatially and temporally heterogeneous patterns. -

Prevention of Outburst Floods from Periglacial Lakes at Grubengletscher, Valais, Swiss Alps

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2001 Prevention of outburst floods from periglacial lakes at Grubengletscher, Valais, Swiss Alps Haeberli, Wilfried ; Kääb, Andreas ; Vonder Mühll, Daniel ; Teysseire, Philip Abstract: Flood and debris-flow hazards at Grubengletscher near Saas Balen in the Saas Valley, Valais, Swiss Alps, result from the formation and growth of several lakes at the glacier margin and within the surrounding permafrost. In order to prevent damage related to such hazards, systematic investigations were carried out and practical measures taken. The evolution of the polythermal glacier, the creeping permafrost within the large adjacent rock glacier and the development of the various periglacial lakes were monitored and documented for the last 25 years by photogrammetric analysis of annually flown high-resolution aerial photographs. Seismic refraction, d.c. resistivity and gravimetry soundings were performed together with hydrological tracer experiments to determine the structure and stability of a moraine dam at a proglacial lake. The results indicate a maximum moraine thickness of > 100 m; extremely high porosity and even ground caverns near the surface may have resulted from degradation of sub- and periglacial permafrost following 19th/20thcentury retreat of the partially cold glacier tongue. The safety and retention capacity of the proglacial lake were enhanced by deepening and reinforcing the outlet structure on top of the moraine complex. The water level of an ice-dammed lake was lowered and a thermokarst lake artficially drained. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3189/172756501781832575 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-63516 Journal Article Originally published at: Haeberli, Wilfried; Kääb, Andreas; Vonder Mühll, Daniel; Teysseire, Philip (2001). -

Washington's Channeled Scabland

t\D l'llrl,. \·· ~. r~rn1 ,uR\fEY Ut,l\n . .. ,Y:ltate" tit1Washington ALBEIT D. ROSEWNI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Dlnctor DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By J HARLEN BRETZ 9TAT• PIUHTIHO PLANT ~ OLYMPIA, WASH., 1"511 State of Washington ALBERT D. ROSELLINI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By .T HARLEN BRETZ l•or sate by Department or Conservation, Olympia, Washington. Price, 50 cents. FOREWORD Most travelers who have driven through eastern Washington have seen a geologic and scenic feature that is unique-nothing like it is to be found anywhere else in the world. This is the Channeled Scab land, a gigantic series of deeply cut channels in the erosion-resistant Columbia River basalt, the rock that covers most of the east-central and southeastern part of the state. Grand Coulee, with its spectac ular Dry Falls, is one of the most widely known features of this ex tensive set of dry channels. Many thousands of travelers must have wondered how this Chan neled Scabland came into being, and many geologists also have speculated as to its origin. Several geologists have published papers outlining their theories of the scabland's origin, but the geologist who has made the most thorough study of the problem and has ex amined the whole area and all the evidence having a bearing on the problem is Dr. J Harlen Bretz. Dr. -

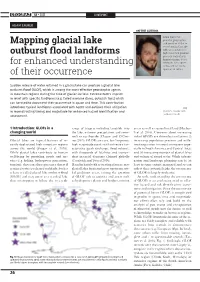

Mapping Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Landforms for Enhanced

GEOGRAZ 68 - 2021 SCHWERPUNKT ADAM EMMER ON THE AUTHOR Adam Emmer is physical geographer Mapping glacial lake and member of the re- search group Cascade with specialization in outburst flood landforms high mountain geomor- phology and natural hazard science. In his for enhanced understanding research, he focuses on hazardous conse- of their occurrence quences of retrea Sudden release of water retained in a glacial lake can produce a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF), which is among the most effective geomorphic agents in mountain regions during the time of glacier ice loss. Extreme GLOFs imprint in relief with specific landforms (e.g. failed moraine dams, outwash fans) which can be used to document their occurrence in space and time. This contribution introduces typical landforms associated with GLOFs and outlines their utilization ting in reconstructing timing and magnitude for enhanced hazard identification and glaciers, mainly lake outburst floods. assessment. 1 Introduction: GLOFs in a range of triggers including landslide into areas as well as agricultural land (Haeber- changing world the lake, extreme precipitation and snow- li et al. 2016). Concerns about increasing melt or earthquake (Clague and O’Con- risk of GLOFs are driven by two factors: (i) Glacial lakes are typical features of re- nor 2015). GLOFs are rare, low frequency, increasing population pressure and settle- cently deglaciated high mountain regions high magnitude events with extreme char- ment expansion in mountain regions (espe- across the world (Shugar et al. 2020). acteristics (peak discharge, flood volume), cially in South America and Central Asia); While glacial lakes contribute to human with thousands of fatalities and tremen- and (ii) increasing number of glacial lakes well-being by providing goods and ser- dous material damages claimed globally and volume of stored water. -

1 Reply to Comments 1 We Would Like to Thank the Three Anonymous

1 Reply to comments 2 We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers and Marco Jorge for their comments. We are 3 particularly pleased that three of the four reviews thought it was an important paper that should be 4 published, and their constructive criticisms have really helped to improve it. We are disappointed that 5 reviewer #2 thinks that we cannot extract information and meaning from the geomorphological 6 signature of tunnel valleys. But we strongly disagree with this view and our argument is laid out below. 7 That they ignore a large body of literature spanning many disciplines that has shown the importance of 8 geomorphology for investigating landforms genesis we find rather perplexing. The reviewer comments 9 are in black and our replies and revisions in blue. 10 - Stephen Livingstone and Chris Clark 11 12 Short Comment by Marco Jorge 13 INTRODUCTION 14 L80-84 (statement of objective): Consider rephrasing sentence (perhaps revise whole paragraph). 15 Suggest to remove “To rectify this” (to correct this error), because it is about the lack of data rather 16 than error. Scale -> geographic scale; Pattern -> spatial arrangement; Rectify “. .mapping of the size, 17 shape, pattern and [spatial] distribution to better understand spatial properties. .” L84: “constitution” 18 -> Composition? 19 We have replaced “to rectify this” with “Based on previous studies and the availability of DEMs, we 20 are now able to undertake…” (as suggested by reviewer #3), changed “pattern” to “spatial 21 arrangement” and “constitutes” to “is”. 22 Reword the rationale for study area selection; e.g., that the landforms can be mapped from a DEM is 23 unrelated to the study area. -

The 2015 Chileno Valley Glacial Lake Outburst Flood, Patagonia

Aberystwyth University The 2015 Chileno Valley glacial lake outburst flood, Patagonia Wilson, R.; Harrison, S.; Reynolds, John M.; Hubbard, Alun; Glasser, Neil; Wündrich, O.; Iribarren Anacona, P.; Mao, L.; Shannon, S. Published in: Geomorphology DOI: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2019.01.015 Publication date: 2019 Citation for published version (APA): Wilson, R., Harrison, S., Reynolds, J. M., Hubbard, A., Glasser, N., Wündrich, O., Iribarren Anacona, P., Mao, L., & Shannon, S. (2019). The 2015 Chileno Valley glacial lake outburst flood, Patagonia. Geomorphology, 332, 51-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2019.01.015 Document License CC BY General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 09. Jul. 2020 Geomorphology 332 (2019) 51–65 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph The 2015 Chileno Valley glacial lake outburst flood, Patagonia R. -

CATASTROPHIC FLOOD FEATURES at CAMAS PRAIRIE, MONTANA More Unusual Currents in Glacial Lake Missoula

CATASTROPHIC FLOOD FEATURES AT CAMAS PRAIRIE, MONTANA More Unusual Currents in Glacial Lake Missoula 2 CATASTROPHIC FLOOD FEATURES AT CAMAS PRAIRIE, MONTANA More Unusual Currents in Glacial Lake Missoula KEENAN LEE DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND GEOLOGICAL ENGINEERING COLORADO SCHOOL OF MINES GOLDEN COLORADO 80401 2009 3 CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 4 INTRODUCTION 5 LOCATION AND SETTING 5 THE CAMAS PRAIRIE BASIN 6 INFLOW SUBLAKE NOTCHES AND RELATED FEATURES 8 Wills Creek Pass Sublake Notch System 11 Markle Pass Sublake Notch System 13 Big Creek Pass Sublake Notch System 14 Duck Pond Pass Sublake Notch System 16 CAMAS PRAIRIE FLOOD OUTLETS 16 Rainbow Lake Outlet System 16 Perma Outlet System 21 GIANT CURRENT RIPPLES 23 Giant Current Ripple Fields 24 Characteristics of Giant Current Ripples 25 Analysis of Giant Current Ripple Data 28 Comparison of GCRs at Camas Prairie with Other Ripple Studies 29 Analysis of GCR Data to Estimate Paleohydraulic Parameters 30 SUMMARY 31 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 33 REFERENCES 33 TABLES 34 4 ABSTRACT Camas Prairie preserves landforms and bedforms that document catastrophic currents at the bottom of glacial Lake Missoula when its glacier dam broke. Although similar features occur in the scablands of eastern Washington, the currents there were channeled floods that flowed downhill; here the sublake currents often flowed uphill. Similar catastrophic lake-bottom currents have been documented elsewhere only in the Altai flood of Siberia. When the ice dam failed and flooding began, the northern rim of the Camas Prairie Basin and part of the eastern rim were under water, forming sublake divides, or ridges. All flow into the basin came over the basin rims, and all of the lake-bottom currents were flowing uphill to enter the basin. -

The Missoula Flood

THE MISSOULA FLOOD Dry Falls in Grand Coulee, Washington, was the largest waterfall in the world during the Missoula Flood. Height of falls is 385 ft [117 m]. Flood waters were actually about 260 ft deep [80 m] above the top of the falls, so a more appropriate name might be Dry Cataract. KEENAN LEE DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND GEOLOGICAL ENGINEERING COLORADO SCHOOL OF MINES GOLDEN COLORADO 80401 2009 The Missoula Flood 2 CONTENTS Page OVERVIEW 2 THE GLACIAL DAM 3 LAKE MISSOULA 5 THE DAM FAILURE 6 THE MISSOULA FLOOD ABOVE THE ICE DAM 6 Catastrophic Flood Features in Eddy Narrows 6 Catastrophic Flood Features in Perma Narrows 7 Catastrophic Flood Features at Camas Prairie 9 THE MISSOULA FLOOD BELOW THE ICE DAM 13 Rathdrum Prairie and Spokane 13 Cheny – Palouse Scablands 14 Grand Coulee 15 Wallula Gap and Columbia River Gorge 15 Portland to the Pacific Ocean 16 MULTIPLE MISSOULA FLOODS 17 AGE OF MISSOULA FLOODS 18 SOME REFERENCES 19 OVERVIEW About 15 000 years ago in latest Pleistocene time, glaciers from the Cordilleran ice sheet in Canada advanced southward and dammed two rivers, the Columbia River and one of its major tributaries, the Clark Fork River [Fig. 1]. One lobe of the ice sheet dammed the Columbia River, creating Lake Columbia and diverting the Columbia River into the Grand Coulee. Another lobe of the ice sheet advanced southward down the Purcell Trench to the present Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho and dammed the Clark Fork River. This created an enormous Lake Missoula, with a volume of water greater than that of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined [530 mi3 or 2200 km3]. -

Article in Press

ARTICLE IN PRESS Quaternary Science Reviews 24 (2005) 1533–1541 Correspondence$ Fresh arguments against the Shaw megaflood hypothesis. that the Lake Agassiz flood was the ‘‘largest in the last A reply to comments by David Sharpe on ‘‘Paleohy- 100,000 years’’ refers to a different publication (Clarke draulics of the last outburst flood from glacial Lake et al., 2003). We agree that, in terms of peak discharge, Agassiz and the 8200 BP cold event’’ both the Missoula floods (e.g., Clarke et al., 1984; O’Connor and Baker, 1992) and the Altay event (Baker et al., 1993) were indeed larger (roughly 17 Sv for Missoula and 418 Sv for Altay) but the released water 1. The megaflood hypothesis volume was a small fraction of that released from glacial Lake Agassiz (Table 1). Furthermore, the focus of We disagree with the premise underlying most of Clarke et al. (2003) was on abrupt climate change David Sharpe’s comments, namely that the Shaw triggered by freshwater injection to the North Atlantic subglacial megaflood hypothesis enjoys sufficient main- Ocean at 8200 BP: Freshwater volume rather than peak streamacceptance that we were negligent in failing to flood discharge is the relevant measure of flood cite it. Although the literature on Shavian megafloods magnitude for activation of this climate switch. Sharpe’s has grown over the past decade, it is less clear that the comment that ‘‘improved knowledge of additional flood ideas have gained ground. As a recent datum, Benn and terrains is important in assessing the impact of specific Evans (2005) assert that ‘‘most Quaternary scientists outburst floods on rapid climate change’’ seems to miss give little or no credence to the [Shaw] megaflood the point that flood intensity, which controls the interpretation, and it conflicts with an overwhelming geomorphic imprint, is only a second-order influence body of modern research on past and present ice sheet on the climate impact. -

Structural Controls on Englacial Esker Sedimentation: Skeiðara´Rjo¨Kull, Iceland

Annals of Glaciology 50(51) 2009 85 Structural controls on englacial esker sedimentation: Skeiðara´rjo¨kull, Iceland Matthew J. BURKE,1 John WOODWARD,1 Andrew J. RUSSELL,2 P. Jay FLEISHER3 1School of Applied Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST, UK E-mail: [email protected] 2School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK 3Earth Sciences Department, State University of New York, Oneonta, NY 13820-4015, USA ABSTRACT. We have used ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to observe englacial structural control upon the development of an esker formed during a high-magnitude outburst flood (jo¨kulhlaup). The surge- type Skeiðara´rjo¨kull, an outlet glacier of the Vatnajo¨kull ice cap, Iceland, is a frequent source of jo¨kulhlaups. The rising-stage waters of the November 1996 jo¨kulhlaup travelled through a dense network of interconnected fractures that perforated the margin of the glacier. Subsequent discharge focused upon a small number of conduit outlets. Recent ice-marginal retreat has exposed a large englacial esker associated with one of these outlets. We investigated structural controls on esker genesis in April 2006, by collecting >2.5 km of GPR profiles on the glacier surface up-glacier of where the esker ridge has been exposed by meltout. In lines closest to the exposed esker ridge, we interpret areas of englacial horizons up to 30 m wide and 10–15 m high as an up-glacier continuation of the esker sediments. High-amplitude, dipping horizons define the -

Pleistocene Lake Outburst Floods and Fan Formation Along the Eastern

ARTICLE IN PRESS Quaternary Science Reviews 25 (2006) 2729–2748 Pleistocene lake outburst floods and fan formation along the eastern Sierra Nevada, California: implications for the interpretation of intermontane lacustrine records Douglas I. Benna,b,Ã, Lewis A. Owenc, Robert C. Finkeld, Samuel Clemmense aSchool of Geography and Geosciences, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK bDepartment of Geology, UNIS, PO Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Norway cDepartment of Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221-0013, USA dCenter for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA 94550, USA eInstitute of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Wales, Aberystwyth SY23 3DB, UK Received 10 June 2005; accepted 5 February 2006 Abstract Variations in the rock flour fraction in intermontane lacustrine sediments have the potential to provide more complete records of glacier fluctuations than moraine sequences, which are subject to erosional censoring. Construction of glacial chronologies from such records relies on the assumption that rock flour concentration is a simple function of glacier extent. However, other factors may influence the delivery of glacigenic sediments to intermontane lakes, including paraglacial adjustment of slope and fluvial systems to deglaciation, variations in precipitation and snowmelt, and lake outburst floods. We have investigated the processes and chronology of sediment transport on the Tuttle and Lone Pine alluvial fans in the eastern Sierra Nevada, California, USA, to elucidate the links between former glacier systems located upstream and the long sedimentary record from Owens Lake located downstream. Aggradation of both fans reflects sedimentation by three contrasting process regimes: (1) high magnitude, catastrophic floods, (2) fluvial or glacifluvial river systems, and (3) debris flows and other slope processes. -

Poster C11E-0718

C11E-0718: What controlled the distribution of Laurentide eskers? Tracy A. Brennand1, Darren B. Sjogren2, and Matthew J. Burke1 1Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University; 2Department of Geography, University of Calgary; Corresponding author: [email protected]. 929 The Problem C) Numerical ice sheet models have been used to explain landform patterns [1] and landform patterns have been used to 919 test numerical ice sheet models [2]. Neither approach is robust unless underlying assumptions are consistent with the landform record. Eskers are the casts of ice-walled channels and are a common landform within the footprint of the last 0 macroform Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS). Most Laurentide eskers formed in subglacial to low englacial ice tunnels [3], a condition -scale 1 Ridge that likely favoured their preservation. However, there is considerable debate over a) whether they formed gradually 0 150 from astronomically-forced meltwater flows [1, 2] or rapidly from glacial lake or surge-related outburst floods [4, 5], b) 20 100 whether they formed in segments time-transgressively [1, 2] or synchronously along their length [3, 4, 5], and c) 929 whether their distribution is mainly controlled by bed deformability [6], bed permeability and groundwater flow [2, 7], 50 sediment supply [8] or climate/water supply [3]. It is imperative that these debates be resolved so that the underlying 919 40 0 9 Direction assumptions of numerical models are robust. Here we approach the problem from first principles, asking first what 29 Flow 50 B) ) basic conditions are required for esker formation and what controls these conditions, then assessing the evidence for l s 9 each of these controls 1) at the scale of the LIS and 2) in southern Alberta where eskers are relatively small.