SOME PROBLEMS PERTAINING to Tile PENINSULAR GNEISSIC COMPLEX Just As in Human Affairs Where the So-Called 'Eternal Triangle'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sedimentational, Structural and Migmatitic History of the Archaean Dharwar Tectonic Province, Southern India

Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. (Earth Planet. Sci.), Vol. 100, No. 4, December 1991, pp. 413-433. Printed in India. Sedimentational, structural and migmatitic history of the Archaean Dharwar tectonic province, southern India K NAHA 1, R SRINIVASAN 2 and S JAYARAMa 1Department of Geology and Geophysics, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur 721 302, India 2National Geophysical Research Institute, Hyderabad 500007, India aDepartment of Mines and Geology, Karnataka State, Lai Bagh Road, Bangalore,560027, India MS received 27 July 1991 Abstract. The earliest decipherable record of the Dharwar tectonic province is left in the 3-3 Ga old gneissic pebbles in some conglomerates of the Dharwar Group, in addition to the 3"3-3-4Ga old gneisses in some areas. A sialic crust as the basement for Dharwar sedimentation is also indicated by the presence of quartz schists and quartzites throughout the Dharwar succession. Clean quartzites and orthoquartzite-carbonate association in the lower part of the Dharwar sequence point to relatively stable platform and shelf conditions. This is succeeded by sedimentation in a rapidly subsiding trough as indicated by the turbidite-volcanic rock association. Although conglomerates in some places point to an erosional surface at the contact between the gneisses and the Dharwar supracrustai rocks, extensive remobilization of the basement during the deformation of the cover rocks has largely blurred this interface. This has also resulted in accordant style and sequence of structures in the basement and cover rocks in a major part of the Dharwar tectonic province. Isoclinal folds with attendant axial planar schistosity, coaxial open folds, followed in turn by non-coaxial upright folds on axial planes striking nearly N-S, are decipherable both in the "basement" gneisses and the schistose cover rocks. -

Streaming of Saline Fluids Through Archean Crust

Lithos 346–347 (2019) 105157 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Lithos journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/lithos Streaming of saline fluids through Archean crust: Another view of charnockite-granite relations in southern India Robert C. Newton a,⁎, Leonid Ya. Aranovich b, Jacques L.R. Touret c a Dept. of Earth, Planetary and Spaces, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA b Inst. of Ore Deposits, Petrography, Mineralogy and Geochemistry, Russian Academy of Science, Moscow RU-119017, Russia c 121 rue de la Réunion, F-75020 Paris, France article info abstract Article history: The complementary roles of granites and rocks of the granulite facies have long been a key issue in models of the Received 27 June 2019 evolution of the continental crust. “Dehydration melting”,orfluid-absent melting of a lower crust containing H2O Received in revised form 25 July 2019 only in the small amounts present in biotite and amphibole, has raised problems of excessively high tempera- Accepted 26 July 2019 tures and restricted amounts of granite production, factors seemingly incapable of explaining voluminous bodies Available online 29 July 2019 of granite like the Archean Closepet Granite of South India. The existence of incipient granulite-facies metamor- phism (charnockite formation) and closely associated migmatization (melting) in 2.5 Ga-old gneisses in a quarry Keywords: fl Charnockite exposure in southern India and elsewhere, with structural, chemical and mineral-inclusion evidence of uid ac- Granite tion, has encouraged a wetter approach, in consideration of aqueous fluids for rock melting which maintain suf- Saline fluids ficiently low H2O activity for granulite-facies metamorphism. -

Karnataka: State Geology and Mineral Maps – Geological Survey of India

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION NO. 30 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE STATES OF INDIA PART VII – Karnataka & Goa Compiled By GeologicalOPERATION :Survey Karnataka & Goa of India Bangalore 2006 CONTENTS Page No. Section-1: Geology and Mineral Resources of Karnataka I. Introduction 1 II. Physiography 1 III. Geology 2 Sargur Group 5 Peninsular Gneissic Complex and Charnockite 5 Greenstone belts 7 Closepet Granite 10 Mafic-ultramafic complexes 11 Dyke Rocks 12 Proterozoic (Purana) Basins 12 Deccan Trap 13 Warkali Beds 13 Laterite 13 Quaternary Formations 14 Recent alluvial soil and rich alluvium 14 IV. Structure 14 Folds 15 Shear zones, Faults and Lineaments 15 V. Mineral Resources Antimony 16 Asbestos 17 Barytes 17 Basemetals (Cu, Pb, Zn) 18 Bauxite 18 Chromite 21 Clay 22 Corundum 23 Diamond 24 Dolomite 25 Feldspar 25 GeologicalFuller's Earth Survey of India25 Garnet 26 Gemstones 26 Gold 28 Graphite 33 Gypsum 33 Iron Ore 33 Kyanite and sillimanite 35 ii Limestone 35 Lithium 37 Magnesite 38 Manganese ores 38 Molybdenite 40 Nickel 40 Ochre 40 Ornamental stones and dimension stones 41 Felsite, fuchsite quartzite 43 Phosphorite 43 Platinoids 43 Quartz 44 Silica sand 44 Radioactive and Rare Earth Minerals 45 Steatite (Soap stone) 45 Tin 46 Titaniferous & vanadiferous magnetite 46 Tungsten 47 Vermiculite 47 Section 2 Geology and Mineral Resources of Goa I. Introduction 48 II. Physiography 48 III. Geology 49 IV. Mineral Resources 51 Bauxite 51 Chromite 52 Clay 52 Iron Ore 52 Limestone 53 Manganese -

Subsurface Topography of Supra Crustals of Dharwar Craton Through Inversion of Regional Bouguer Gravity

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2016, 7(5): 54-89 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Subsurface topography of Supra crustals of Dharwar Craton through inversion of Regional Bouguer Gravity Bhagya K. and Ramadass G. Center of Exploration Geophysics, Osmania University, Hyderabad _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Regional gravity data have been analyzed to estimate the supra crustal thickness in parts of Dharwar Craton (73°30' E to 78° 30' E and latitude 12° N to 17°N). The depositions of supra crustal four deep seated faults and several other lineaments were delineated from qualitative analysis of Bouguer gravity. The supracrustal (Charnokite, Younger granites, Closepet granite, Sargur belt, Chitradurga schist belt, Bababudan group , Deccan Basalt, Bhima sediments, and western part of Cuddapah Sediments) as well as deep crustal (Peninsular gneiss, Upper crustal and deeper crust layer ( up to Moho) structural configuration in the Dharwar craton were obtained via the inversion of modeling of eleven east-west traverses ( T1 to T 11) digitized from the Bouguer gravity contour map. The sub-surface configuration of each of these supra crustal layers were obtained by digitizing the corresponding crustal structure and presented as 3D contour map reveal structural complexity with plunging synclines, anticlines and refolded along E-W trending warps. The peninsular gneissic layer is very uneven in geometry varying in thickness from 6.9 to 11 km, upper crustal layer varies between 18.2 to 24.55 km and deep crustal layer 34 km to 40 km . Key words: Crustal configuration, supracrustal, anticlines, synclines, up warps, plunging _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Earlier geophysical studies in the Dharwar craton include gravity [67]; [19]; [21]; [28]; Magsat [30]. -

Police Station List

PS CODE POLOCE STATION NAME ADDRESS DIST CODEDIST NAME TK CODETALUKA NAME 1 YESHWANTHPUR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 2 JALAHALLI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 3 RMC YARD PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 4 PEENYA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 5 GANGAMMAGUDI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 6 SOLADEVANAHALLI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 7 MALLESWARAM PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 8 SRIRAMPURAM PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 9 RAJAJINAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 10 MAHALAXMILAYOUT PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 11 SUBRAMANYANAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 12 RAJAGOPALNAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 13 NANDINI LAYOUT PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 14 J C NAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 15 HEBBAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 16 R T NAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 17 YELAHANKA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 18 VIDYARANYAPURA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 19 SANJAYNAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 20 YELAHANKA NEWTOWN PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 21 CENTRAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 22 CHAMARAJPET PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 23 VICTORIA HOSPITAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 24 SHANKARPURA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 25 RPF MANDYA MANDYA 22 MANDYA 5 Mandya 26 HANUMANTHANAGAR PS BANGALORE -

Tectonic Framework for Precambrian Sedimentary Basins in India

1 1 The Archean and Proterozoic History of Peninsular India: Tectonic 2 Framework for Precambrian Sedimentary Basins in India 3 4 Joseph G. Meert1 and Manoj K. Pandit2 5 1Department of Geological Sciences, 241 Williamson Hall, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611 USA 6 2Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur 302004, Rajasthan, India 7 2 8 Abstract 9 The Precambrian geologic history of peninsular India covers nearly 3.0 billion years of time. The Peninsula 10 is an assembly of five different cratonic nuclei known as the Aravall-Bundelkhand, Eastern Dharwar, Western 11 Dharwar, Bastar and Singhbhum cratons along with the Southern Granulite Province. Final amalgamation of these 12 elements occurred either by the end of the Archaean (2.5 Ga) or the end of the Paleoproterozoic (~1.6 Ga). Each of 13 these nuclei contains one or more sedimentary basins (or metasedimentary basins) of Proterozoic age. This paper 14 provides an overview of each of the cratons and a brief description of the Precambrian sedimentary basins in India 15 that form the focus of the remainder of this book. In our view, it appears that basin formation and subsequent clo- 16 sure can be grossly constrained to three separate intervals that are related to the assembly and disaggregation of the 17 supercontinents Columbia, Rodinia and Gondwana. The oldest Purana-I basins developed during the 2.5-1.6 Ga in- 18 terval, Purana-II basins formed during the 1.6-1.0 Ga interval and the Purana-III basins formed during the 19 Neoproterozoic-Cambrian interval. 20 21 Introduction 22 Peninsular India represents an amalgam of ancient cratonic nuclei that formed and 23 stabilized during Archaean to Paleoproterozoic (3.8-1.6 Ga). -

A Sage Par Excellence

A Sage Par Excellence Biography of Jagadguru Shankaracharya Sri Sacchidananda Shivabhinava Narasimha Bharati Mahaswamiji, the 33rd Acharya of Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri www.sringeri.net © Sri Sri Jagadguru Shankaracharya Mahasamsthanam Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri - 577 139 www.sringerisharadapeetham.org A Sage Par Excellence Published by: Vidya Bharati Press (An in-house publication wing of Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham Sringeri - 577 139, Karnataka Ph: 08265 250123) © Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri First Edition: May 2010 (1000 copies) ISBN: 978-81-910191-1-7 Printed at: Vidya Bharati Press Shankarapuram, Bangalore - 560 004 Contributionwww.sringeri.net value: Rs. 25/- This book is distributed at a highly subsidized value for the sustenance© and propagation of Sanatana Dharma, and to reach all sections of the society. The contribution value received for this book is used for charitable purposes. Copies available at: Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri – 577 139 ii Preface Twelve centuries back, Jagadguru Sri Adi Shankaracharya established His first and foremost Peetham, the Dakshinamnaya Sringeri Sri Sharada Peetham for the sustenance and propagation of Sanatana-Dharma. Since then, the Peetham has been adorned by an unbroken chain of Acharyas who have been erudite scholars and dispassionate saints. Out of their innate compassion, the Jagadgurus have been incessantly teaching the path of Dharma to the multitude of Their disciples, through Their very lives, Their teachings and by the establishment of temples, Pathashalas and other charitable institutions. The 33rd Acharya of the Peetham, Jagadguru Sri Sacchidananda Shivabhinava Narasimha Bharati Mahaswamijiwww.sringeri.net was a great yogi, a repository of Shastraic knowledge, an expert in Mantra-Shastra and an epitome of compassion.© A life sketch of the Mahaswamiji was first published in Kannada by the Peetham in 1924. -

01.Personal Profile 02. Educational Qualification

01.PERSONAL PROFILE Name DEEPA K C Designation ASSISTANT PROFESSOR Qualification M A .M.Ed. UGC NET Specialization FOLKLORE Research experience NIL Official Address PES COLLEGE OF SCIENCE,ARTS AND COMMERCE.MANDYA Residential Address W/O SURESH K R. #1876/2,Vinodha Road, 6th Cross Subhash Nagar,Mandya-571401 Date of Birth 20-07-1980 Contact Number 8453307784 E-Mail [email protected] 02. EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION SL.NO. DEGREE BOARD/UNIVERSITY YEAR OF GRADE PASSING 01 BA MYSORE 2001 SECOND UNIVERSITY CLASS 02 B.Ed, TUMKUR 2011 FIRST CLASS UNIVERSITY 03 M.A MYSORE 2003 DISTINCTION UNIVERSITY 04 M.Ed, UNIVERSITY OF 2014 DISTINCTION MYSORE 05 NET NEW DELHI 2013 PASS 03. TEACHING EXPERIENCE SL.NO. COLLEGE DESIGNATION CLASSES YEAR TAUGHT 01 P.E.S. College of Science Assistant Professor kannada 2014 to till Arts and Commerce, today Mandya 02 Jr.College Lecturer Kannada 2012 to 2014 Amruthur,Kunigal,Tumkur 04. RESEARCH ARTICLES PUBLICATION 1. I Have Published “AMBIGARA CHOWDAIAH” Articles in the year 2019. 05. RESEARCH PAPER PRESENTATIONS 01.Participated in Two Days National Seminor on “KARNATAKA NATAKA PARAMPARE” on 22nd to 23rd March 2019. Organized by KLE Shivayogi Murugendra Swamiji Mahavidyala, ATHANI, BELGUM. 02. Participated in One days Seminar on “VACHANA KRANTHIYA PUNARUTHHANA” on 23rd February 2018. Organized by Akhila Bharatha Sharana Sahithya Parishath, Mysore. 03. Participated in One days Seminar on “KANNADA SAHITYA MATTU JANAPADA” on 21st September 2018.Organized by Karnataka Janapada Parishad, Bengaluru. 04. Participated in One days Seminar on “MENTAL HEALTH SYMPOSIUM” on 20th August 2016.Organized by District Legal Services Authority, Mandya. 05. -

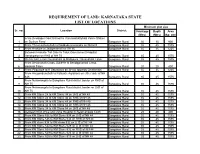

REQUIREMENT of LAND: KARNATAKA STATE LIST of LOCATIONS Minimum Plot Size Sr

REQUIREMENT OF LAND: KARNATAKA STATE LIST OF LOCATIONS Minimum plot size Sr. no. Location District Frontage Depth Area (Mtrs) (Mtrs) (Sq. mtr) From Devalapur Govt School to Thirumashettyhalli Police Station 1 on Soukya Road Bangalore Rural 30 30 900 2 From Thirumashettyhalli to Doddadunnasandra on NH 648 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 3 From Hoskote to Jadigenahalli on SH 95 Bangalore Rural 35 35 1225 Between Hoskote Toll Gate to Taluk Government Hospital, 4 Dandupalya on RHS of NH 75 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 5 On NH 648, From Devanahalli to Mallepura, Devanahalli Taluk Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 From Devanahalli Cross, Sulibele to Bendiganahalli Cross, 6 Hoskote Taluk Bangalore Rural 20 20 400 7 From Piligumpe to K Satyawara on SH 82 towards Chintamani Bangalore Rural 35 35 1225 From Anugondanahalli to Kalkunte Agrahara on either side of NH 8 648 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 From Nelamangala to Bangalore Rural district border on RHS of 9 NH 75 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 From Nelamangala to Bangalore Rural district border on LHS of 10 NH 75 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 11 From KM Stone 24 to KM Stone 34 on LHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 12 From KM Stone 24 to KM Stone 34 on RHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 13 From KM Stone 34 to KM Stone 44 on RHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 14 From KM Stone 44 to KM Stone 54 on RHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 15 From KM Stone 34 to KM Stone 54 on LHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 16 Between KEB office and Usha Hospital in Nelamangala Town Bangalore Rural 20 20 400 17 From -

Government of India Ministry of Mines Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 858 to Be Answered on 07.02.2019 Geological Survey Of

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF MINES LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 858 TO BE ANSWERED ON 07.02.2019 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA 858. DR. SHASHI THAROOR: Will the Minister of MINES be pleased to state: (a) whether the Geological Survey of India (GSI) has a comprehensive repository of geological structures in the country; (b) if so, the details thereof; (c) if not, whether the Government proposes to create such a repository and if so, the details thereof; (d) whether GSI has a policy for geological conservation, to protect unusual rock types, landforms that preserve records of natural events of the past, significant fossil localities, stratigraphic sections, areas where significant advances in geology have been made, and deposits of particular minerals; and (e) if so, the details thereof and if not, whether the Government proposes to create such a policy and if so, the details thereof? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE FOR MINES AND COAL (SHRI HARIBHAI PARTHIBHAI CHAUDHARY) (a) to (e): Geological Survey of India (GSI) has identified many sites of unique geological importance and exceptional geomorphic expression/ landscapes. It has designated 32 various such types of naturally preserved geological structures/ monuments as geo-heritage sites/ national geological monuments across the country for protection and maintenance. The details of these sites are as follows: S. Geological heritage site / S. Geological heritage site / No National geological monument No National geological monument ANDHRA PRADESH MAHARASHTRA 1. Volcanogenic bedded Barytes, 22. Lonar Lake, Buldana Dist. Mangampeta, Cuddapah District (Dist.). 2. Eparchaean Unconformity, Chittor Dist. CHATTISGARH 3. Natural Geological Arch, Tirumala Hills, 23. -

Statewise Food Safety Officers

Statewise Food Safety Officers SL. PHONE NO PHONE NO Sl. No DISTRICT NAME OF THE TALUKS NAME OF THE OFFICER E-Mail ID NO (MOBILE NUMBER) (OFFICE NUMBER) 1 1 Bagalkote Badami DR. TANDUR B.A 9448960239 08357 220194 [email protected] 2 2 Bagalkote Bagalkote DR. RAJKUMAR YARAGAL 9448103116 08354-201393 [email protected] 3 3 Bagalkote Bilagi DR. JAYASHREE 9902460600 08425-276451 [email protected] 4 4 Bagalkote Hungund DR. KUMAMAGI 9448730519 08351-260545 [email protected] 5 5 Bagalkote Jamkhandi Dr.BASAVARAJ 9902835559 08353-220384 [email protected] 6 6 Bagalkote Mudhol Dr. S M POJARI 9449768303 08350-281448 [email protected] 7 7 Bangalore Rural Devanahalli Dr.B A LATHA 9480316647 080-27403773 [email protected] 8 8 Bangalore Rural Doddaballapur Dr.SHIVARAJ 9341896005 080-7627174 [email protected] 9 9 Bangalore Rural Hoskote DR.SHAKILA 9008002511 080-27905910 [email protected] 10 10 Bangalore Rural Nelamangala Dr.NARSIMAJIIA 9916973248 080-7722808 [email protected] 11 11 Bangalore Urban Anekal Dr.KUMAR 9448560757 080-784451 [email protected] 12 12 Bangalore Urban Banagalore North Dr.MANGALAMBA.K.S. 9986545777 080-28461630 [email protected] 13 13 Bangalore Urban Bangalore East Dr.CHANDRASHEKARAIAH 9448332195 080-25612400 [email protected] 14 14 Bangalore Urban Bangalore South Dr. SRIVANI 8277515760 080-26320890 [email protected] 15 15 Belgaum Athani Dr.SANJAY R DUMGOL 9008927880 08289-285428 [email protected] 16 16 Belgaum Bailhongal Dr.RAJUPUT P U 9448758463 08288-237233 [email protected] 17 17 Belgaum Belgaum DR. GOPAL KRISHNA NAIK 9448870168 0831-2482886 [email protected] DR. ISHWARAPPA S 18 18 Belgaum Chikodi 9980418436 08338-275056 [email protected] HEBBALLI 19 19 Belgaum Gokak Dr.R S BENCHINAMARDI 9972619159 08332-229475 [email protected] 20 20 Belgaum Hukkeri Dr.S V MUNNYAL 9448132380 08333-266048 [email protected] 21 21 Belgaum Khanapur Dr. -

Political Milieu During Kempe Gowda: the Founder of Bangalore

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(5): 113-115 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Political milieu during Kempe Gowda: The founder of Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2016; 2(5): 113-115 Bangalore www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 27-03-2016 Accepted: 28-04-2016 Dr. Munirajappa, Dr. Venkatesha TS Dr. Munirajappa Principal and Associate Abstract Professor, Rural College, The Yelahanka Nadu, the minor principality contributed to the glory of Vijayanagara Empire during the Kanakapura- 562117 early part of the 14th Century AD. Hiriya Kempegowda was one of the three confidants of King Karnataka Krishna Devaraya which had brought him great reputation. The political dilemmas and the stalemate that cropped up after the demise of Sri Krishna Devaraya became the causes for the rise of Dr. Venkatesha TS Kempegowda, Contemporary political climate came to encounter the spreading popularity of UGC-Post Doctoral Fellow, Kempegowda who had by 1537 founded New Bangalore. This Paper deals the Historical significance, Department of Studies and Political situations, and contributions of Kempegowda during his Tenure. Research in History and Archaeology, Tumkur Keywords: Yelahanka Nada Prabhus, Bairava, Sri Rangaraya, Talikote, Dore Mane (Royal adobe). University, Tumkur- 572103 Karnataka Introduction th Vijayanagara Empire that rose during the early part of 14 Century manifested itself as a great source of cultural enrichment to Indian History, and the reign of the rulers of the empire stands out as a resplendent chapter in the cultural and political history of the country. Hampe dazzled as the capital of the great empire, also was the epitome of the cultural glory and remains today, though in ruins, as a heritage cultural site of world stature.