Music for Dancing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival 2018 Runs June 20-August 26 with 350+ Performances, Talks, Events, Exhibits, Classes & Works

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK FOR IMAGES AND MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Nicole Tomasofsky, Public Relations and Publications Coordinator 413.243.9919 x132 [email protected] JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE FESTIVAL 2018 RUNS JUNE 20-AUGUST 26 WITH 350+ PERFORMANCES, TALKS, EVENTS, EXHIBITS, CLASSES & WORKSHOPS April 26, 2018 (Becket, MA)—Jacob’s Pillow announces the Festival 2018 complete schedule, encompassing over ten weeks packed with ticketed and free performances, pop-up performances, exhibits, talks, classes, films, and dance parties on its 220-acre site in the Berkshire Hills of Western Massachusetts. Jacob’s Pillow is the longest-running dance festival in the United States, a National Historic Landmark, and a National Meal of Arts recipient. Founded in 1933, the Pillow has recently added to its rich history by expanding into a year-round center for dance research and development. 2018 Season highlights include U.S. company debuts, world premieres, international artists, newly commissioned work, historic Festival connections, and the formal presentation of work developed through the organization’s growing residency program at the Pillow Lab. International artists will travel to Becket, Massachusetts, from Denmark, Israel, Belgium, Australia, France, Spain, and Scotland. Notably, representation from across the United States includes New York City, Minneapolis, Houston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Chicago, among others. “It has been such a thrill to invite artists to the Pillow Lab, welcome community members to our social dances, and have this sacred space for dance animated year-round. Now, we look forward to Festival 2018 where we invite audiences to experience the full spectrum of dance while delighting in the magical and historic place that is Jacob’s Pillow. -

9/5/2011-4/21/2012. Letters from a Danceaturg. Neil Baldwin to Lori Katterhenry

9/5/2011-4/21/2012. Letters from a Danceaturg. Neil Baldwin to Lori Katterhenry. No.1 - September 5, 2011 Dear Lori: I am grateful to Ryoko Kudo, Maxine Steinman and our MSU dancers for opening the doors to the studio in Life Hall last week and welcoming me to sit in on three sessions of the setting of excerpts from There is a Time (1956) by Jose Limon. They worked on “Opening Circle,” “Plant and Reap,” “Mourn,” “Laugh and Dance,” and “Hate & War.” Reviewing and editing my on-site notes, I recalled a helpful observation by Doris Humphrey in The Art of Making Dances with regard to this work. She writes, “There is a Time states its thematic material in the opening section and builds all the rest of its many parts on variations of the same movements. Unfortunately, this escapes most people; what they see is a suite form, contrasted ideas of dramatic or lyric significance. This is because the eye is not sufficiently trained to remember movement themes, and will usually miss them completely.” Indeed, the fact that the original title of There is a Time was Variations on a Theme came through powerfully during these sessions. Ryoko’s precisely-planned and at the same time intuitively- executed method was the embodiment of Limon’s preliminary concept notes for the dance, when he said that “the community…form[s] a very close circle which pulsates symbolizing an ovum or womb in travail…[T]he large circle…symbolize[s] time – the great continuity – eternal, unbroken…without hurry and without end.” I was also mindful of a point that Carla Maxwell made in an interview with The New York Times ten years ago about classic modern dance: “What's indispensable is a consistent point of view that relates to the times,'' she said. -

Registration Packet 2015-16

! Registration Packet 2015-16 Faculty Artur Sultanov, Artistic Director Mr. Sultanov was born and raised in St. Petersburg, Russia. He trained at Vaganova Ballet Academy and at age 17, joined the Kirov ballet where he danced a classical repertoire. Artur has also performed with Eifman Ballet as a Soloist. In 2000 he moved to San Francisco to join Alonzo King’s Lines Ballet. In 2003 Artur joined Oregon Ballet Theatre. His principal roles at OBT include the Prince in Swan Lake, Ivan in Firebird, and the Cavalier in the Nutcracker, among others. Mr. Sultanov has performed on the stages of the Metropolitan Opera House, Kennedy Center, Bolshoi Ballet Theatre, and the Mariisnky Theatre in his native city of St. Petersburg. In addition to being an accomplished dancer, Mr. Sultanov has also taught extensively throughout his professional career. In the past eight years, Mr. Sultanov has taught and choreographed for the school of Oregon Ballet Theatre and Lines Contemporary Ballet School of San Francisco. His vast experience also includes holding master workshops in the Portland Metro Area, Seaside, OR, Vancouver and Tacoma, Washington. Artur Sultanov is excited to be a part of the Portland dance community and is looking forward to inspiring a new generation of dancers. Vanessa Thiessen Vanessa Thiessen is originally from Portland, OR. She trained at the School of Oregon Ballet Theatre, with James Canfield, and continued on to dance for Oregon Ballet Theatre from 1995-2003. At OBT she danced leading roles in Gissele and Romeo and Juliet. After moving to San Francisco in 2003, she danced with Smuin Ballet, ODC Dance, Amy Seiwert’s Imagery, Opera Parallele and Tanya Bello’s Project b. -

Securing Our Dance Heritage: Issues in the Documentation and Preservation of Dance by Catherine J

Securing Our Dance Heritage: Issues in the Documentation and Preservation of Dance by Catherine J. Johnson and Allegra Fuller Snyder July 1999 Council on Library and Information Resources Washington, D.C. ii About the Contributors Catherine Johnson served as director for the Dance Heritage Coalition’s Access to Resources for the History of Dance in Seven Repositories Project. She holds an M.S. in library science from Columbia University with a specialization in rare books and manuscripts and a B.A. from Bethany College with a major in English literature and theater. Ms. Johnson served as the founding director of the Dance Heritage Coalition from 1992 to 1997. Before that, she was assistant curator at the Harvard Theatre Collection, where she was responsible for access, processing, and exhibitions, among other duties. She has held positions at The New York Public Library and the Folger Shakespeare Library. Allegra Fuller Snyder, the American Dance Guild’s 1992 Honoree of the Year, is professor emeritus of dance and former director of the Graduate Program in Dance Ethnology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She has also served as chair of the faculty, School of the Arts, and chair of the Department of Dance at UCLA. She was visiting professor of performance studies at New York University and honorary visiting professor at the University of Surrey, Guildford, England. She has written extensively and directed several films about dance and has received grants from NEA and NEH in addition to numerous honors. Since 1993, she has served as executive director, president, and chairwoman of the board of directors of the Buckminster Fuller Institute. -

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 Pm

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 pm Photo:Photo: Benoit © Paul Lemay Kolnik 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PETER MARTINS ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATOR JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH THE DANCERS PRINCIPALS ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING CHASE FINLAY ABI STAFFORD SOLOIST UNITY PHELAN CORPS DE BALLET MARIKA ANDERSON JACQUELINE BOLOGNA HARRISON COLL CHRISTOPHER GRANT SPARTAK HOXHA RACHEL HUTSELL BAILY JONES ALEC KNIGHT OLIVIA MacKINNON MIRIAM MILLER ANDREW SCORDATO PETER WALKER THE MUSICIANS ARTURO DELMONI, VIOLIN ELAINE CHELTON, PIANO ALAN MOVERMAN, PIANO BALLET MASTERS JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH CRAIG HALL LISA JACKSON REBECCA KROHN CHRISTINE REDPATH KATHLEEN TRACEY TOURING STAFF FOR NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES COMPANY MANAGER STAGE MANAGER GREGORY RUSSELL NICOLE MITCHELL LIGHTING DESIGNER WARDROBE MISTRESS PENNY JACOBUS MARLENE OLSON HAMM WARDROBE MASTER MASTER CARPENTER JOHN RADWICK NORMAN KIRTLAND III 3 Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop Photo © Paul Kolnik for all of your instrument, EVENT SPONSORS accessory, and service needs! RICHARD AND MARY JO STANLEY ELLIE AND PETER DENSEN ALLYN L. MARK IOWA HOUSE HOTEL SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Season Sponsor! Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop for all of your instrument, accessory, and service needs! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! THE PROGRAM IN THE NIGHT Music by FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Choreography by JEROME ROBBINS Costumes by ANTHONY DOWELL Lighting by JENNIFER TIPTON OLIVIA MacKINNON UNITY PHELAN ABI STAFFORD AND AND AND ALEC KNIGHT CHASE FINLAY ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING Piano: ELAINE CHELTON This production was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. -

Alvinailey Study Guide 05 06.Indd

1906 05/06 Centennial Season 2006 Study Guide Alvin Ailey SchoolTime American Dance Theater Thursday, March 2, 2006, at 11:00 am Zellerbach Hall Welcome February 23, 2006 Dear Educator and Students, Welcome to SchoolTime! On Thursday, March 2, at 11:00 a.m., you will attend the SchoolTime performance of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. This study guide will help you prepare your students for their experience in the theater and give you a framework for how to integrate the performing arts into your curriculum. Targeted questions and activities will help students understand the context for Alvin Ailey’s world reknowned dance work, Revelations and provide an introduction to the art form of modern dance. Please feel free to copy any portion of this study guide. Study guides are also available online at http://cpinfo.berkeley.edu/information/education/study_guides.php. Your students can actively participate at the performance by: • OBSERVING the physical and mental discipline demonstrated by the dancers • LISTENING attentively to the music and lyrics of the songs chosen to accompany the dance • THINKING ABOUT how music, costumes and lighting contribute to the overall effect of the performance • REFLECTING on what they experienced at the theater after the performance We look forward to seeing you at the theater! Sincerely, Laura Abrams Rachel Davidman Director Education Programs Administrator Education & Community Programs About Cal Performances and SchoolTime The mission of Cal Performances is to inspire, nurture and sustain a lifelong appreciation for the performing arts. Cal Performances, the performing arts presenter and producer of the University of California, Berkeley, fulfi lls this mission by presenting, producing and commissioning outstanding artists, both renowned and emerging, to serve the University and the broader public through performances and education and community programs. -

Download Reviews

Book Reviews Ian Payne, The Almain in Britain, c.1549– c.1675: a dance manual from manuscript sources. Ashgate, Aldershot, 2003. ISBN 0-85967-965-9. xxi+268 pp, £42.50. This book is in essence an extended study of the ‘Old Measures in particular (1993) and he is prepared to accept Measures’ and of the seven manuscript sources in which they Ward’s conjecture that the Old Measures constituted a stand- are described. Payne focuses especially on the English Almain, ard beginners’ course in the dancing schools. From this it for which these manuscripts afford the only information, but seems to follow that, as far as Payne is concerned, no one went neglects none of the associated dances, whether they are to a dancing school and made notes of what he was taught formally part of the Old Measures or not. He provides unless he was already at the Inns of Court or was a child with reconstructions of most of the dances described, using a aspirations to do so. In truth, as Ward has cogently argued, for deliberately plain style, and makes informed comments about most of the manuscripts in which the Old Measures are the available music. The whole corpus is presented in the recorded, any connection with the Inns of Court is either context of his personal view of the development of social tenuous or non-existent. dance in Britain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Unfortunately, the author is not equally well equipped for Dating of the manuscripts every part of his task, with the result that the book inevitably When the contents of a commonplace book do not form a invites comparison with the Curate’s Egg. -

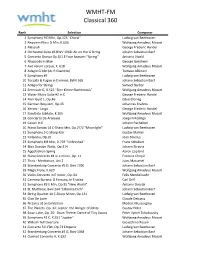

Top 360 Countdown

WMHT-FM Classical 360 Rank Selection Composer 1 Symphony 9 D Min, Op.125 "Choral" Ludwig van Beethoven 2 Requiem Mass D Min, K.626 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 3 Messiah George Frederic Handel 4 Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String Johann Sebastian Bach 5 Concerto Grosso Op.8/1 E Four Seasons "Spring" Antonio Vivaldi 6 Rhapsody in Blue George Gershwin 7 Ave verum corpus, K. 618 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 8 Adagio G Min (Ar R.Giazotto) Tomaso Albinoni 9 Symphony #5 Ludwig van Beethoven 10 Toccata & Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 Johann Sebastian Bach 11 Adagio for Strings Samuel Barber 12 Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 13 Water Music Suite #2 in D George Frederic Handel 14 Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 Edvard Grieg 15 German Requiem, Op.45 Johannes Brahms 16 Xerxes - Largo George Frederic Handel 17 Exsultate Jubilate, K 165 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 18 Concierto De Aranjuez Joaquin Rodrigo 19 Canon in D Johann Pachelbel 20 Piano Sonata 14 C-Sharp Min, Op.27/2 "Moonlight" Ludwig van Beethoven 21 Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min Gustav Mahler 22 Finlandia, Op.26 Jean Sibelius 23 Symphony 8 B Min, D.759 "Unfinished" Franz Schubert 24 Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 Johann Strauss 25 Appalachian Spring Aaron Copland 26 Piano Concerto #1 in e minor, Op. 11 Frederic Chopin 27 Thais - Meditation, Act 2 Jules Massenet 28 Brandenburg Concerto #5 D, Bwv 1050 Johann Sebastian Bach 29 Magic Flute, K.620 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 30 Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

The Power of Dance How Your Passion and Appreciation Provides Opportunity and Growth

BALLET ARIZONA DONOR IMPACT Foundation Highlight: Donor Spotlight: Letter From the Q&A: Mayo Clinic Tracy Olson Executive Director: Artistic Director REPORT Samantha Turner Ib Andersen TURNING POINTE The Power of Dance How your passion and appreciation provides opportunity and growth. Ballet Arizona dancers in Theme and Variations. Choreography by George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust. Photo by Rosalie O'Connor. SPRING From the main stage to classrooms across the Valley, dance continues to inspire and bring people together. As the curtain begins to close on our 2018 – 2019 season, I BEHIND THE SCENES am reminded about the power of dance. This spring season with Ib Andersen is an ode to that power and we begin with a celebration of George Balanchine. I am excited that we are finally bringing Q: What can audiences expect from the Emeralds to the Arizona stage for All Balanchine. This is one of Balanchine’s most poetic ballets. From the choreography to the Balanchine program this year? music, is it a treat for both dancers and audiences. Of course, A: A lot of dancing! But in all seriousness, this program is very rich we end the season at Desert Botanical Garden with Eroica. This with three very different ballets, all having three very distinct styles. is one of my favorite ballets that I have created and it should be even better than last year! Theme and Variations is so exciting to watch. Balanchine created this ballet in 1947 for American Ballet Theatre. It was an homage In this issue, Executive Director Samantha Turner talks about to Marius Petipa and a continuation of his old style of ballet the impact new works have on ballet in today’s world. -

Kinder Educational Materials 2020

“Rhythms and Patterns” Kinder Concert 2020Canton Symphony Orchestra Learning Materials PreK - 1st Grade The Canton Symphony Orchestra presents the “Rhythms and Patterns” learning materials. These lessons willchallenge students to see how math and music are intertwined. With orchestral music, students will discover patterns in music through these unique lessons. By looking for patterns, these activities willcreatively demonstrate the common ground between math and music, and show their deep connection. Use the following learning materials in lieu of our traditional concert experience to give students aglimpse of what would have been discussed at the concert. Provided are both simple and advanced musical activities that can be done in the home. Look through the activities and choose what will work for you. Page 2 - Vocab List Page 3 - Simple MusicActivities Pages 4-27 - Advanced Activities (For a link to all music recordings, visit https://www.cantonsymphony.org/kinder-concert/) Written By: Rachel Hagemeier, Holly Fox and Sandra Simpson For more information contact Rachel Hagemeier, Education andCommunity Kinder Concert 2020 - Vocab List • Overture - an orchestral piece at the beginning of an opera, suite, play, oratorio, or other extended composition. • Opera - a form of theatre in which music has a leading role and the parts are taken by singers. • Symphony - an elaborate musical composition for full orchestra, typically in four movements, at least one of which is traditionally in sonata form. • Musical Form - the structure of a musical composition or performance. • Pattern - a regular and intelligible form or sequence discernible in certain actions or situations. • Melody - a sequence of single notes that is musically satisfying. -

The Balanchine Trust: Dancing Through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing

Volume 6 Issue 2 Article 2 1999 The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing Cheryl Swack Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Cheryl Swack, The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing, 6 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 265 (1999). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol6/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Swack: The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licen THE BALANCHINE TRUST: DANCING THROUGH THE STEPS OF TWO-PART LICENSING CHERYL SWACK* I. INTRODUCTION A. George Balanchine George Balanchine,1 "one of the century's certifiable ge- * Member of the Florida Bar; J.D., University of Miami School of Law; B. A., Sarah Lawrence College. This article is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Allegra Swack. 1. Born in 1904 in St. Petersburg, Russia of Georgian parents, Georgi Melto- novich Balanchivadze entered the Imperial Theater School at the Maryinsky Thea- tre in 1914. See ROBERT TRAcy & SHARON DELONG, BALANci-NE's BALLERINAS: CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MUSES 14 (Linden Press 1983) [hereinafter TRAcY & DELONG]. His dance training took place during the war years of the Russian Revolution. -

Tarantism and Tarantella in a Doll's House

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives SANDRA COLELLA TARANTISM AND TARANTELLA IN A DOLL’S HOUSE MASTER THESIS IBSEN STUDIES 2007 INDEX INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………pg 3 CHAPTER 1 TARANTELLA IN A DOLL’S HOUSE . IBSENIAN SCHOLARS’ VIEWS..........………………………………………………...…...pg 15 CHAPTER 2 TARANTISM AND TARANTELLA. BERGSØE’S TREATISE AND THE SCANDINAVIAN STUDIES…………………………………………………….pg 31 CHAPTER 3 THE ITALIAN FOLK DANCE TARANTELLA………………………………………..….pg 45 CHAPTER 4 THE PHENOMENON OF TARANTISM. DE MARTINO’S WORKS AND THE OTHER STUDIES……………………………………………………………..…pg 55 CHAPTER 5 TARANTISM AND TARANTELLA IN A DOLL’S HOUSE . A NEW HYPOTHESIS OF INTERPRETATION……………………………………….…pg 85 CONCLUSION...………………………………………………………………………………pg 99 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………....…pg 101 2 INTRODUCTION Echoes of the controversies about the meaning of the drama A Doll’s House and Nora’s character continue to reach us from 1879, the year in which Ibsen completed his probably most famous work in Amalfi. Up till now, the complexity of the characters and the wise webbing of the drama, scattered of symbolic moments, widening its study, are the cause of divergent interpretations by the scholars. An example, exemplifying for all the discussions, could be the famous problem of Ibsen’s “feminism”. In the chapter “The poetry of feminism” in her book Ibsen’s women the American scholar Joan Templeton (2001) tries to say a definitive word about the sense to attribute to the drama. She quotes an impressive series of evidences with great accuracy, coming not only from works, but also from specific events and stands of which Ibsen was protagonist, to be opposed to only one point in favour of the detractors of the feminist vision about A Doll’s House .