Laurence S. Kuenning the Bunyan-Burrough Debate of 1656-7 Analysed Using a Computer Hypertext (Westminster Theological Seminary: Unpublished Phd Thesis, 2000)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Light Within the Light Within Is the Fundamental and Immediate Experience for Friends

Readings for “Quaker Basics”, Week 2 John 1:9 (NRSV)1 9 The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world. [a] John 1:9 Or He was the true light that enlightens everyone coming into the world Matthew 28:20 (NRSV) 20 and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” [a] Matthew 28:20 Other ancient authorities add Amen Isaiah 7:14 (NRSV) 14 Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. Look, the young woman[a] is with child and shall bear a son, and shall name him Immanuel. [b] Isaiah 7:14 Gk the virgin Isaiah 7:14 That is God is with us Matthew 1:23 (NRSV) 23 “Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel,” which means, “God is with us.” http://www.pym.org/faith-and-practice/friends-beliefs-and- practices/the-light-within/ The Light Within The Light Within is the fundamental and immediate experience for Friends. It is that which guides each of us in our everyday lives and brings us together as a community of faith. It is, most importantly, our direct and unmediated experience of the Divine. Friends have used many different terms or 262.09607 phrases to designate the source and inner certainty B655Q of our faith—a faith which we have gained by direct Week2 1 New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), copyright © 1989 the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. -

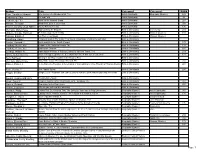

Column1 Column2 Column3 Column4 Column5 Column6 Column7 Column8 Column9 Column10 Column11 AUTHOR TITLE CALL PUBLISHER City PUB

Column1 Column2 Column3 Column4 Column5 Column6 Column7 Column8 Column9 Column10 Column11 AUTHOR TITLE CALL PUBLISHER City PUB. COPY# SUBJECT 1 SUBJECT 2 SUBJECT 3 NOTES NUMBER DATE Aarek, William From Loneliness to Fellowship: a Swarthmore George Allen London 1954 1 Quakerism, Psychology study in psychology and Lecture & Unwin Ltd. Introduction Quakerism Pamphlets Aarek, William From Loneliness to Fellowship: a Swarthmore George Allen London 1954 2 Quakerism, Psychology study in psychology and Lecture & Unwin Ltd. Introduction Quakerism Pamphlets Abbott, Margery Post Christianity and the Inner Life: PH #402 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 2009 1 Christianity - Twenty-First Century Reflections Spiritual Life on the Words of Early Friends Abbott, Margery Post To Be Broken and Tender: A 289.6 Western 2010 1 Quaker Quaker theology for today Ab2010to Friend Theology Abbott, Margery Post, Walk Worthy of Your Calling, 289.6 Friends Richmond, IN 2004 1 Pastoral Travel - Parsons, Peggy Quakers and the Traveling Ministry Ab2004wa United Press Theology - Religious Senger eds. Society of Aspects Friends Abbott, Margery Post; Historical Dictionary of Friends 289.6 Scarecrow Lanham, MD 2003 1 Society of Chijoke, Marry Ellen; (Quakers) Ab2003hi Press Friends - Dandelion, Pink; History - Oliver, John William Dictionary Abrams, Irwin To the Seeker Brochure Friends Philadelphia ND 1 Quakerism, General Introduction Conference Alexander, Horace Everyman's Struggle For Peace PH #74 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 1953 2 Pendle Hill Pamphlet Alexander, Horace G. Gandhi Remembered PH#165 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 1969 1 Pendle Hill Gandhi, Pamphlet Mohandas - Non- violence Alexander, Horace G. Quakerism in India PH #31 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA ND 1 Pendle Hill Pamphlet Alexander, Horace G. -

Early Friends

Children of the Light-Roots and Transitions, 1647-1677 Robert Griswold Talk given at the Colorado Regional Spring Gathering April 18, 2021 Though reality is all around us, people have always preferred to live in a virtual reality of their own making. There was, however, a strange group of people who arose in England in the mid-17th century. They didn’t fit in socially. And they scorned all of the available religions known to them. This included all the branches of Christianity. They considered the steeple houses, the creeds, the hireling priests, the sacraments and rituals all to be an abomination and corruption. They were certain that these religions were deceptions that shut people into a virtual reality and away from any real spiritual life. They had a new vision that arose from within them, not from what they might have been told. They gathered in homes and in open places, sitting or standing in silence. Sometimes these odd folks came into the local churches and castigated the people there for being all wrong in their religious practice. They often got beat up or thrown out. They claimed to have a new authority called an inward light. They said what mattered was being true to the Inward Light found in silence. They had a life changing vision. What worried people around them was that this group of “light” folks kept growing until there were hundreds of them. And this group challenged the virtual reality constructed by the society around them. I think it is hard for us today to realize just how radical this vision was and how much it worried the people around them. -

Quaker Manual of Style and Glossary

make these apparent and assure an appropriate group has reached a particular place of decision or outcome. shared understanding, and to test whether this sense Quaker: Originally, a derogatory term applied to Friends of the meeting is in accord with the group’s faithful Quakers because their excitement of spirit when led to speak in obedience to the leading of the Spirit. a meeting for worship was sometimes expressed in a Silence/Silent Worship: Expectant, living silence, not shaking or quaking motion. Now this term is simply merely the absence of noise. The quietude of Friends an alternative designation for a member of the meeting for worship—and other periods of observant Religious Society of Friends. worship—embodies the special quiet of listeners, the Quaker Process: A catch-all expression often used to special perception of seekers, the special alertness of describe the various and collective techniques by those who wait. The silence invites the sharing of which Quakers make decisions and go about their messages which arise from a stirring of the Spirit. Quaker other business. Quaker process can include discern- Standing Aside: An action taken by an individual who has ment, threshing, worship-sharing, sense of the genuine reservations about a particular decision, but Meeting, and other methodological terms described who also recognizes that the decision is clearly sup- Manual of in this glossary. These constituent aspects have in ported by the weight of the Meeting. The action of common a commitment to obedience to the leading standing aside allows the Meeting to reach unity. of the Spirit. -

From Plainness to Simplicity: Changing Quaker Ideals for Material Culture J

Chapter 2 From Plainness to Simplicity: Changing Quaker Ideals for Material Culture J. William Frost Quakers or the Religious Society of Friends began in the 1650s as a response to a particular kind of direct or unmediated religious experience they described metaphorically as the discovery of the Inward Christ, Seed, or Light of God. This event over time would shape not only how Friends wor shipped and lived but also their responses to the peoples and culture around them. God had, they asserted, again intervened in history to bring salvation to those willing to surrender to divine guidance. The early history of Quak ers was an attempt by those who shared in this encounter with God to spread the news that this experience was available to everyone. In their enthusiasm for this transforming experience that liberated one from sin and brought sal vation, the first Friends assumed that they had rediscovered true Christianity and that their kind of religious awakening was the only way to God. With the certainty that comes from firsthand knowledge, they judged those who op posed them as denying the power of God within and surrendering to sin. Be fore 1660 their successes in converting a significant minority of other English men and women challenged them to design institutions to facilitate the ap proved kind of direct religious experience while protecting against moral laxity. The earliest writings of Friends were not concerned with outward ap pearance, except insofar as all conduct manifested whether or not the person had hearkened to the Inward Light of Christ. The effect of the Light de pended on the previous life of the person, but in general converts saw the Light as a purging as in a refiner’s fire (the metaphor was biblical) previous sinful attitudes and actions. -

A Quaker Weekly

• A Quaker Weekly VOLUME 3 DECEMBER 7, 1957 NUMBER 49 IN THIS ISSUE ~TAND ruham'd and Collecting Whittieriana almost despairing before holy and pure ideals. As I read the by C. Marshall Taylor New Testament I feel how weak, irresolute, and frail I am, and how little I can rely Whittier~ Quaker Liberal and Reformer on any thing save our God's by Howard W. Hintz mercy and infinite compas sion, which I reverently and thankfully own have followed me through life, and the as Most Winning Spokesman of the surance of which is my sole Moral Life ground of hope for myself, and for those I love and pray by Anna Brinton for. -JoHN GREENLEAF WHITTIER William Edmondson and Ireland's -First Quaker Meeting by Caroline N. Jacob PRICE OF THIS SPECIAL ISSUE TWENTY CENTS Internationally Speaking $4.50 A YEAR 786 FRIENDS JOURNAL Decennber 7, 1957 Internationally Speaking FRIENDS JOURNAL RESIDENT EISENHOWER, speaking to the nation Pabout science and security, referred to "a great step toward peace" as being as necessary as a great leap into • outer space in connpetition with the developnnents of the Russian satellites. The probability that space satellites are a step toward the developnnent of intercontinental nnissiles ennphasizes the innportance of the great step toward peace, as does the suggestion that local NATO connnnanders are to have authority to decide whether a' Published weekly at 1616 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 2, situation requires response with atonnic weapons. This Pennsylvania (Rittenhouse 6-7669) By Friends Publishing Corporation latter suggestion innplies the end of national sovereignty. -

Quakers in America

“I expect to pass through life but once. If therefore, there be any kindness I can show, or any good thing I can do to any fellow being, let me do it now, and not defer or neglect it, as I shall not pass this way again.” - William Penn Quaker Affirmations Quaker History, Part 2: W M Penn, Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-00455 Quakers in America Quaker Affirmation, Lesson 2 Quaker history in 3 segments: 1. 1647 – 1691: George Fox • Begins with the ministry of George Fox until the time of his death, and encompasses the rise and swift expansion of the Friends movement 2. 1691 – 1827: The Age of Quietism 3. 1827 – present: Fragmentation, Division & Reaffirmation 2 Review: • Fox sought to revive “Primitive Christianity” after a revelation of Christ in 1647 and a vision of “a great people to be gathered” in 1652. • Many people in England were resentful of the government-led church and longed for a more meaningful spiritual path. • A group of Friends dubbed “The Valiant Sixty” traveled the country and the world to preach Fox’s message. • Around 60,000 people had joined the Society of Friends by 1680. • Friends in mid-1600s were often persecuted for their George Fox beliefs, and George Fox was often in prison. • George Fox and many other Friends came to America 1647 - 1691 to preach. 3 George Fox, Courtesy Library of Congress, LC=USZ62-5790 Review: What was the essence of Fox’s message? • There is that of God in everyone. • The Inner Light lives within; it discerns between good and evil and unites us. -

Faith and Practice (1960) Pacific Yearly Meeting: Faith and Practice (1973) Philadelphia Yearly Meeting: Faith and Practice (Revised 1972)

FAITH AND PRACTICE THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE OHIO VALLEY YEARLY MEETING OF THE RELIGIOUS SOCIETY OF FRIENDS June 24, 2019 Revision Committee Edition Ohio Valley Yearly Meeting is in the process of revising its Book of Faith & Practice, formerly known as the Book of Discipline. Revisions and additions that have been updated by the revision committee or proposed for approval by the Yearly Meeting are included in this electronic version. Because the revision process is not complete, there is no printed version of the book that includes the new material. Last Fully Revised in 1978 1 Selected Sections Revised in 2007, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019 (see footnotes) Ohio Valley Yearly Meeting received inspiration and adapted language from materials in the Suggested Reading List and from the following Friends Disciplines: Iowa Yearly Meeting of Friends (Conservative) Discipline (1974) London Yearly Meeting Christian Faith and Practice (1960) Pacific Yearly Meeting: Faith and Practice (1973) Philadelphia Yearly Meeting: Faith and Practice (Revised 1972) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................... 5 Civic Responsibilities ................................. 25 Citizenship .............................................. 25 Listening to the Spirit ...................................... 6 Obedience to Law & Civil Disobedience 25 Meeting for Worship ..................................... 6 Treatment of Civic Offenders ................. 25 Preparation for Worship ........................... -

The Religion Quaker Journalist

The Religion of the Quaker Journalist By Howard H. Brinton SHREWSBURY LECTURE THE SHREWSBURY LECTURES Shrewsbury Meeting was already established in 1672, when George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, visited America. He says in his Journal, published by Cambridge University Press: “And soe wee came to Shrewsberry & on the first day of the weeke wee had a pretious meet- tinge… & friends & other people came farr to this Meettinge; & on ye 2d of the 7th month wee had a mens (& weomens) Meettinge, out of the most parts of ye new Country Jarsie, which will be of great service in keepinge ye Gospell order & Government of Christ Jesus…and there is a Monthly & A Generall Meettinge sett up and they are buildinge A Meettinge place in the midst of them.” In preparation for the tercentenary, in 1972, of George Fox’s visit to America, an annual Shrewsbury Lecture is given on some basic aspect of Quakerism. A particular phase of the spe- cial emphasis which Quakerism gives to the Christian message is presented. The community and Monmouth County in particular are invited on this occasion, known as Old Shrewsbury Day, to join with Friends who “came farr to this Meettinge” to learn together from him who is the Light of the World. The Religion of the Quaker Journalist By Howard H. Brinton SHREWSBURY LECTURE Given at Shrewsbury Friends Meeting Highway 35 and Sycamore Avenue Shrewsbury, New Jersey Sixth Month 17, 1962 JOHN WOOLMAN PRESS, INC. 4002 North Capitol Avenue Indianapolis 8, Indiana 1962 Copyright 1962, JOHN WOOLMAN PRESS, INC. PREFACE “Journals” were not an exclusively Quaker phenomenon. -

Edna M. Hall the Theology of Samuel Fisher, Quaker (University of Birmingham: Bachelor of Divinity Thesis, 1960)

Edna M. Hall The Theology of Samuel Fisher, Quaker (University of Birmingham: Bachelor of Divinity thesis, 1960) An analysis of the theology of Samuel Fisher, in the context of the controversies in which he engaged, and centred on his view of the doctrine of the inner light, and its implications for soteriology (doctrine of salvation), ecclesiology (doctrine/study of the church), and pneumatology (doctrine/study of the Holy Spirit), and the authority of Scripture. Keywords: Samuel Fisher; Light, Christ, Holy Spirit, Church, Scripture and its authority; early Quaker theology, soteriology, ecclesiology, pneumatology, controversy between Quakers and Protestants. Who it would be useful for: Theologians and historians of Quakerism. Biographical Introduction Fisher was born in Northampton in 1605, the son of a local tradesman, and ordained in the Church of England after graduating from Oxford in 1630. He became a Baptist in 1643, and after an active and disputatious ministry, underwent convincement as a Quaker in 1655 as a result of the preaching of Caton and Stubbs at Dover. The year after his convincement he attempted to deliver a ‘prophetic message’ before Lord Protector Cromwell and Parliament, but was held down and silenced. Thereafter he was active as a minister and writer, travelled extensively, including on the continent, and was imprisoned several times. His most notable work is Rusticos ad Academicos, the subject of Hall’s study, the only apology for Quakerism ‘from the early period undertaken by a writer with a training in the ancient languages and in theology’. As such he is an important figure. However, as a theologian he is ‘able rather than profound’, and a ‘shrewd controversialist rather than a powerful thinker’. -

Author Title Category1 Category2 PHP# Page 1

Author Title Category1 Category2 PHP# Blom, Dorothea Johnson Life Journey of a Quaker Artist, The Arts & Spirituality Biography (Quaker) 232 Eichenberg, Fritz Art and Faith Arts & Spirituality 68 Eichenberg, Fritz Artist on the Witness Stand Arts & Spirituality 257 Havens, Teresina Mind What Stirs in your Heart Arts & Spirituality 304 Thorne, Dorothy Lloyd Gilbert Poetry Among Friends Arts & Spirituality 130 Morrison, Mary Chase Approaching the Gospels Bible & Christianity Community 219 Lantero, Erminie Huntress Feminine Aspects of Divinity Bible & Christianity Women (Quaker) 191 Watson, Elizabeth Let Their Lives Speak Bible & Christianity Women (Quaker) Armstrong, Karen History of God, A: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam Bible & Christianity Brinton, Howard H. Light and Life in the Fourth Gospel Bible & Christianity 179 Cadbury, Henry Joel Eclipse of the Historical Jesus, The Bible & Christianity 133 Cadbury, Henry Joel Behind the Gospels Bible & Christianity 160 Durland, William R. Apocalyptic Witness: A Radical Calling for our own Times, The Bible & Christianity 279 Jones, Rufus Matthew Thou Dost Open Up My Life: Selections from the Rufus Jones Collection Bible & Christianity 127 Kern, Kathleen Getting in the Way: Studies in the Book of Acts Bible & Christianity Morrison, Mary Chase Way of the Cross: The Gospel Record, The Bible & Christianity 260 Palmer, Parker J. In the Belly of a Paradox: A Celebration of Contradictions in the Thought of Thomas Merton Bible & Christianity 224 Peck, George T. The Psalms Speak Bible & Christianity 298 Phipps, Beckey Simple Lives * Radiant Faith: Bible Lessons from the 2004 Annual Gathering of Friends Bible & Christianity Spears, Joanne and Larry Friendly Bible Study Bible & Christianity Urner, Carol R. -

Reading Background on Readings Reflections

Quakerism 101 Unit C Quaker Universalism January 31, 2010 Reading Samuel D. Caldwell, ªThe Inward Light: How Quakerism Unites Universalism and Christianity.º Dan Seeger, ªThe Place of Universalism in the Society of Friends, or Is Coexistence Possible?º Background on Readings Samuel D. Caldwell, former General Secretary of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, presented ªThat Blessed Principal ¼ ª as an address to the Quaker Universalist Fellowship in 1988. It is a clear, succinct argument for a Quaker Christian Universalist perspective. Dan Seeger, Executive Secretary of Pendle Hill until 2002, is a writer and spokesperson for a Quaker universalism that recognizes and draws from the spiritual wealth of many religious traditions. This article is one of many he has written on this general theme. Reflections Please reflect on the following questions as you read and once you have read the reading. What do you believe? Write down, in a few sentences, some of the religious beliefs you hold that are important to you. How did you come to these beliefs? What experiences in your life have shaped your religious beliefs? What characteristics does Sam Caldwell list for the light? How does his description fit your experience? How is Friends© concept of the Light universalist? How is it Christian? What is ªpseudo-universalismº? Why does Sam Caldwell see it as threatening to Quakerism? Do you agree? Defend your perspective. How would you react if Milwaukee Meeting declared that it was not a Christian group? Why? How would you respond if Milwaukee Meeting said