Evaluation of the Economic and Social Impacts of the Skye Bridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

From Portree, Isle of Skye (A87 Heading South)

From Portree, Isle of Skye (A87 heading South) 2 Main Routes are outlined. Route 1 is the most direct over the Bealach Na Ba. Own Road Route 1 Transport 1. Head South on the A87 (signposted Kyleakin, Kyle of Lochalsh); 2. At the Kyleain Roundabout take the 1st exit onto the A87; 3. Cross the Skye Bridge; 4. Drive through Kyle of Lochalsh, (turn left at the 2nd set of lights and then right then left you should see signposts for Lochcarron); 5. Continue through Balmacara to Auchtertyre; 6. Just past Auchtertyre, turn left onto the A890 (signposted Gairloch, Locharron); 7. Continue towards Lochcarron passing Achmore, Stromeferry and Strathcarron; 8. Just past Strathcarron, turn left at the junction onto the A896; 9. You will see Applecross on the signpost!; 10. Continue and pass through Lochcarron and then on through Kishorn; 11. You will start to see the hills of Applecross on your left as you drive past Loch Kishorn; 12. At Tornapress turn left onto the Bealach Na Ba, prepare to be amazed; 13. Continue until you reach Applecross at the other side!; 14. Once you have come over the cattlegrid continue around the bend to the bottom of the brae (hill); 15. Turn left here and the Inn is approx. 300m on your left. Route 2 – as route 1 until point 11 THEN 12. At Tornapress continue towards Sheildaig on the A896 through the glen; 13. About a mile before Sheildaig turn left towards Applecross; 14. Continue, passing through Arrina, Kenmore, Fernamore, Callakille and Lonbain; 15. You will pass a big sand dune on your right as you go up a hill; 16. -

The Manse, Main Street, Kyle of Lochalsh, IV40 8DA Property Description

The Manse, Main Street, Kyle of Lochalsh, IV40 8DA Property Description Five-bedroom extended detached bungalow located in the picturesque village of Kyle. Set within the beautiful Scottish landscape in the county of Ross-shire the property presents a wonderful opportunity to purchase on the much sought after northwest coast of Scotland. The bright and spacious property benefits from a flexible floor plan and good sized rooms throughout. It has scope for many future uses and has excellent features including double glazing and storage space. The accommodation comprises: Ground Floor - Entrance porch, hall, living room, dining room, kitchen, utility room, five bedrooms, bathroom and shower room. Gross Internal Floor Area: 145 square metres. Externally the property features garden grounds to the front side and rear. The front garden is a mixture of grass, colourful trees and shrubbery. A driveway with space for numerous cars leads to a detached garage which offers a multi-use space. There is also a fully enclosed rear garden. Local Area Kyle of Lochalsh is a lively highland village with many local amenities including banks, shops, supermarket and butchers. There are many leisure activities in the area such as a leisure pool & gym, hotels, restaurants and bars. Additional facilities include a chemist, dentist surgery & medical centre. There is a primary school within the village and secondary schooling is available in the nearby village of Plockton to which a school bus runs daily. There is a railway station within the village which offers direct services to Inverness where the airport (106 miles) has regular domestic and international flights. -

John Clegg & Co

BROADFORD FARM LAND Broadford, Isle of Skye 33.23 Hectares / 82.11 Acres John Clegg & Co CHARTERED SURVEYORS & FORESTRY AGENTS BROADFORD FARM LAND Lot 1 Development Plot 0.22 Ha/0.54 Ac Offers over £45,000 Broadford 1 mile Kyle of Lochalsh 10 miles Portree 26 miles Fort William 83 miles (Distances are approximate) BROADFORD FARM LAND 33.23 Hectares / 82.11 Acres Lot 3 An opportunity to acquire potential development and forestry planting land in a striking location on the beautiful Isle of Skye. FREEHOLD FOR SALE IN 3 LOTS OR AS A WHOLE Lot 1 Lot 2 Lot 3 Development Plot Riverside Fields Potential Planting Scheme 0.22 Ha/0.54 Ac 7.07 Ha / 17.47 Ac 25.94 Ha / 64.10 Ac Offers over £45,000 Offers over £35,000 Offers over £35,000 AS A WHOLE OFFERS OVER £115,000 SOLE SELLING AGENTS John Clegg & Co, 2 Rutland Square, Edinburgh EH1 2AS Tel: 0131 229 8800 Fax: 0131 229 4827 Ref: J M Lambert MRICS Lot 3 Lot 1 Lot 2 LOCATION AUTHORITIES Broadford Farm Land is located just south of the village of Favourable grants provide excellent financial incentives for Forestry Commission Scotland The Highland Council Broadford, on the eastern side of the Isle of Skye. The farm woodland creation with potential returns available from the Highland & Islands Conservancy Glenurquhart Road benefits from local amenities and breath-taking landscapes, sitting establishment of a commercial crop. ‘Woodlands’ - Fodderty Way Inverness both in the shadow of Beinn na Caillich and less than two miles Dingwall IV15 9XB IV3 5NX from Broadford Bay. -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

Towards a Sonic Methodology Cathy

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 11, No. 2, 2016, pp. 343-358 Mapping the Outer Hebrides in sound: towards a sonic methodology Cathy Lane University of the Arts London, United Kingdom [email protected] ABSTRACT: Scottish Gaelic is still widely spoken in the Outer Hebrides, remote islands off the West Coast of Scotland, and the islands have a rich and distinctive cultural identity, as well as a complex history of settlement and migrations. Almost every geographical feature on the islands has a name which reflects this history and culture. This paper discusses research which uses sound and listening to investigate the relationship of the islands’ inhabitants, young and old, to placenames and the resonant histories which are enshrined in them and reveals them, in their spoken form, as dynamic mnemonics for complex webs of memories. I speculate on why this ‘place-speech’ might have arisen from specific aspects of Hebridean history and culture and how sound can offer a new way of understanding the relationship between people and island toponymies. Keywords: Gaelic, island, landscape, memory, Outer Hebrides, place-speech, sound © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction I am a composer, sound artist and academic. In my creative practice I compose concert works and gallery installations. My current practice focuses around sound-based investigations of a place or theme and uses a mixture of field recording, interview, spoken text and existing oral history archive recordings as material. I am interested in the semantic and the abstract sonic qualities of all this material and I use it to construct “docu-music” (Lane, 2006). -

2019 Scotch Whisky

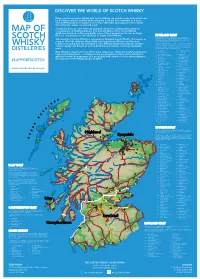

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

14 Kyleside, Kyleakin, Isle of Skye, IV41 8PW

The Isle of Skye Estate Agency Portree Office: [email protected] The Isle of Skye Estate Agency 01478 612 683 Kyle Office: [email protected] www.iosea.co.uk 01599 534 555 14 Kyleside, Kyleakin, Isle of Skye, IV41 8PW. Offers Over £165,000 Semi Detached House Sea Views Oil Central Heating, Double Glazing 3 Bedrooms Enclosed Garden Grounds Private Residents Only Parking Description: 14 Kyleside is a well presented three bedroom semi detached property located in the picturesque village of Kyleakin affording wonderful sea views over Loch Alash, the Skye Bridge and the mainland. 14 Kyleside is a delightful three bedroom property centrally located in Kyleakin close to all amenities and facilities the village has to offer. The property has been well maintained by the current owner and is presented in walk-in condition with bright and spacious living accommodation. The accommodation within is set out over two floors and comprises of hallway, lounge, kitchen, rear porch and bathroom on the ground floor with three bedrooms located on the first floor. The property is decorated in neutral tones throughout and further benefits from UPVC double glazing, oil fired central heating and neat garden grounds. Externally the property sits within well maintained garden grounds which are mainly laid to lawn with shrubs, bushes and an established hedge providing privacy. Additionally the garden hosts two sheds, one with power and private residents only parking is available to the front of the property. 14 Kyleside would make the perfect family home or buy to let property located close to all the local amenities Kyleakin has to offer, all with exclusive sea views. -

Your Detailed Itinerary Scotland Will Bring You to the A96 to the North- Its Prehistory, Including the Standing This Is the ‘Outdoor Capital’ of the UK

Classic Scotland Classic Your Detailed Itinerary Scotland will bring you to the A96 to the north- its prehistory, including the Standing This is the ‘outdoor capital’ of the UK. east. At Keith, you can enjoy a typical Stones at Calanais, a setting of great Nearby Nevis Range, for example, is a Day 1 distillery of the area, Strathisla. presence and mystery which draws ski centre in winter, while, without Day 13 From Jedburgh, with its abbey visitor many to puzzle over its meaning. snow, it has Britain’s longest downhill Glasgow, as Scotland’s largest city, centre, continue northbound to (Option here to stay for an extra day mountain bike track, from 2150 ft offers Scotland’s largest shopping experience the special Borders to explore the island.) Travel south to (655m), dropping 2000ft (610m) over choice, as well as museums, galleries, landscape of rolling hills and wooded Day 4/5 Tarbert in Harris for the ferry to Uig almost 2 miles (3km). It’s fierce and culture, nightlife, pubs and friendly river valley. Then continue to Go west to join the A9 at Inverness in Skye. demanding but there are plenty of locals. Scotland’s capital, Edinburgh, with its for the journey north to Scrabster, other gentler forest trails nearby. Fort choice of cultural and historic ferryport for Orkney. From Stromness, William also offers what is arguably attractions. Explore the Old Town, the Stone Age site of Skara Brae lies Scotland’s most scenic rail journey, the city’s historic heart, with its quaint north, on the island’s west coast. -

Scottish Isles and Norwegian Fjords

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Scottish Isles AND Norwegian Fjords UNESCO World Heritage Site Cruise Itinerary Aurlandsfjord Land Routing Norwegian Sognefjord Train Routing Sea Flåm Air Routing Pre-Program Routing Myrdal Lerwick Shetland Islands Stalheim Kirkwall Bergen Oslo Portree Orkney Islands NORWAY Isle of Skye Kyle of Lochalsh Fort William Glencoe Edinburgh Glasgow DENMARK SCOTLAND Irish North Sea Copenhagen Sea May 26 to June 3, 2022 Sognefjord u Shetland Islands u Orkney Islands Join us for this custom-designed, seven-night Isle of Skye u Scottish Highlands u Glasgow voyage to Norway’s majestic fjords and Scotland’s 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada Orkney and Shetland Islands. Cruise from Bergen, Norway, 2 Bergen, Norway/ to Glasgow, Scotland, aboard the exclusively chartered, Embark Le Dumont-d’Urville Five-Star small ship Le Dumont-d’Urville. 3 Bergen Travel in the wake of Viking explorers, cruising into 4 Flåm Railway/Cruising Sognefjord ports accessible only by small ship. Ride Norway’s Flåm Railway, one of the world’s most scenic rail 5 Lerwick, Shetland Islands, Scotland, for Jarlshof journeys, and enjoy a full-day excursion into the 6 Kirkwall, Orkney Islands, Scottish Highlands. Visit Neolithic Orkney— for Ring of Brodgar and Skara Brae including a special presentation by the Ness of Brodgar 7 Kyle of Lochalsh for Portree, Isle of Skye archaeological site director and head archaeologist, 8 Fort William for the Scottish Highlands Nick Card—and tour Bergen’s UNESCO-inscribed 9 Glasgow, Scotland/Disembark ship/ Bryggen. Norway/Copenhagen Pre-Program and Return to the U.S. -

Sustainability Profile for North Uist and Berneray North Uist & Berneray

Sustainability Profile for North Uist and Berneray North Uist & Berneray CONTENTS Page Introduction 3 Goal 1: Making the most of natural and cultural resources without damaging them 6 Objective 1: Protecting and enhancing natural resources and promoting their value 6 (Includes key topics – sea; fresh water; land; biodiversity; management) Objective 2: Protecting and enhancing cultural resources and promoting their value 9 (Includes key topics – language; arts; traditions; sites/ monuments: management, interpretation) Objective 3: Promoting sustainable and innovative use of natural resources 11 (Includes key topics – agriculture; fisheries and forestry; game; minerals; tourism; marketing) Objective 4: Promoting sustainable and innovative use of cultural resources 13 (Includes key topics – cultural tourism; facilities; projects; products; events; marketing) Goal 2: Retaining a viable and empowered community 14 Objective 5: Retaining a balanced and healthy population 14 (Includes key topics – age structure; gender balance; health; population change; population total/ dispersal) Objective 6: Supporting community empowerment 16 (Includes key topics – community decision-making; control of natural resources; access to funds, information, skills, education, expertise) Objective 7: Ensuring Equal access to employment 18 (Includes key topics – range/ dispersal of jobs; training; childcare provision; employment levels; skills base; business start-up) Objective 8: Ensuring equal access to essential services 20 (Includes key topics – housing; utilities; -

Kyleakin Fish Feed Factory Marine Harvest

Kyleakin Fish Feed Factory Marine Harvest Environmental Impact Assessment - Volume 2 of 4: Main Report Chapter 12: Socio Economic Final May 2017 Marine Har vest Envir onmental Impact Assessment - Volume 2 of 4: Mai n R eport Kyleakin Fish Feed Factory Environmental Statement Contents 12. Socio Economic .................................................................................................................................... 12-1 12.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 12-1 12.1.1 Geographical Scope ............................................................................................................................... 12-1 12.1.2 Planning and Policy Context .................................................................................................................. 12-2 12.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................... 12-3 12.2.1 Assessment Approach............................................................................................................................ 12-3 12.3 Baseline Conditions ................................................................................................................................ 12-4 12.3.1 Population ..............................................................................................................................................