Radiation Pattern, Gain, and Directivity James Mclean, Robert Sutton, Rob Hoffman, TDK RF Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of Radiation Patterns Using Modified Design of Yagi-Uda Antenna G

Adv. Eng. Tec. Appl. 5, No. 1, 7-9 (2016) 7 Advanced Engineering Technology and Application An International Journal http://dx.doi.org/10.18576/aeta/050102 Study of Radiation Patterns Using Modified Design of Yagi-Uda Antenna G. M. Thakur1, V. B. Sanap2,* and B. H. Pawar1. PI, Wireless section, DPW &Adl DG office, Pune (M.S.), India. Yeshwantrao Chavan College, Sillod Dist Aurangabad (M.S.), India. Received: 8 Aug. 2015, Revised: 20 Oct. 2015, Accepted: 28 Oct. 2015. Published online: 1 Jan. 2016. Abstract: Antenna is very important in wireless communication system. Among the most prevalent antennas, Yagi-Uda antenna is widely used. To improve the antenna gain and directivity, design of antenna is always important. In this paper, the Yagi Uda antenna is modified by adding two more reflectors instead of single and the gain, directivity & radiation pattern were studied. This antenna is designed to give better gain in one particular direction as well as somewhat reduced gain in other directions. The direction of "reduced gain" and gain at particular direction are not controllable in Yagi Uda. This paper provides a design which modifies radiation pattern of Yagi as per user requirement. The experiment is carried out at 157 MHz and all readings are taken for vertical polarization, with the help of Radio Communication Monitor. Keywords: Wireless communication, Yagi-Uda, Communication Service Monitor, Vertical polarization. 1 Introduction three) are used. The said antenna is designed with following set of parameters, Antennas have numerous advantages such as they can be Type:- Yagi-Uda antenna with additional two suitably used for wide range of applications such as reflectors wireless communications, satellite communications, pattern Input :- FM modulated signal of 157 MHz, with stability combining and antenna arrays. -

Radiometry and the Friis Transmission Equation Joseph A

Radiometry and the Friis transmission equation Joseph A. Shaw Citation: Am. J. Phys. 81, 33 (2013); doi: 10.1119/1.4755780 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.4755780 View Table of Contents: http://ajp.aapt.org/resource/1/AJPIAS/v81/i1 Published by the American Association of Physics Teachers Related Articles The reciprocal relation of mutual inductance in a coupled circuit system Am. J. Phys. 80, 840 (2012) Teaching solar cell I-V characteristics using SPICE Am. J. Phys. 79, 1232 (2011) A digital oscilloscope setup for the measurement of a transistor’s characteristic curves Am. J. Phys. 78, 1425 (2010) A low cost, modular, and physiologically inspired electronic neuron Am. J. Phys. 78, 1297 (2010) Spreadsheet lock-in amplifier Am. J. Phys. 78, 1227 (2010) Additional information on Am. J. Phys. Journal Homepage: http://ajp.aapt.org/ Journal Information: http://ajp.aapt.org/about/about_the_journal Top downloads: http://ajp.aapt.org/most_downloaded Information for Authors: http://ajp.dickinson.edu/Contributors/contGenInfo.html Downloaded 07 Jan 2013 to 153.90.120.11. Redistribution subject to AAPT license or copyright; see http://ajp.aapt.org/authors/copyright_permission Radiometry and the Friis transmission equation Joseph A. Shaw Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana 59717 (Received 1 July 2011; accepted 13 September 2012) To more effectively tailor courses involving antennas, wireless communications, optics, and applied electromagnetics to a mixed audience of engineering and physics students, the Friis transmission equation—which quantifies the power received in a free-space communication link—is developed from principles of optical radiometry and scalar diffraction. -

25. Antennas II

25. Antennas II Radiation patterns Beyond the Hertzian dipole - superposition Directivity and antenna gain More complicated antennas Impedance matching Reminder: Hertzian dipole The Hertzian dipole is a linear d << antenna which is much shorter than the free-space wavelength: V(t) Far field: jk0 r j t 00Id e ˆ Er,, t j sin 4 r Radiation resistance: 2 d 2 RZ rad 3 0 2 where Z 000 377 is the impedance of free space. R Radiation efficiency: rad (typically is small because d << ) RRrad Ohmic Radiation patterns Antennas do not radiate power equally in all directions. For a linear dipole, no power is radiated along the antenna’s axis ( = 0). 222 2 I 00Idsin 0 ˆ 330 30 Sr, 22 32 cr 0 300 60 We’ve seen this picture before… 270 90 Such polar plots of far-field power vs. angle 240 120 210 150 are known as ‘radiation patterns’. 180 Note that this picture is only a 2D slice of a 3D pattern. E-plane pattern: the 2D slice displaying the plane which contains the electric field vectors. H-plane pattern: the 2D slice displaying the plane which contains the magnetic field vectors. Radiation patterns – Hertzian dipole z y E-plane radiation pattern y x 3D cutaway view H-plane radiation pattern Beyond the Hertzian dipole: longer antennas All of the results we’ve derived so far apply only in the situation where the antenna is short, i.e., d << . That assumption allowed us to say that the current in the antenna was independent of position along the antenna, depending only on time: I(t) = I0 cos(t) no z dependence! For longer antennas, this is no longer true. -

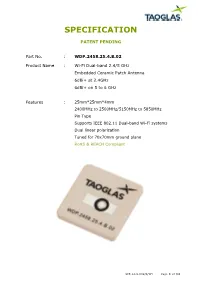

WDP.2458.25.4.B.02 Linear Polarization Wifi Dual Bands Patch

SPECIFICATION PATENT PENDING Part No. : WDP.2458.25.4.B.02 Product Name : Wi-Fi Dual-band 2.4/5 GHz Embedded Ceramic Patch Antenna 6dBi+ at 2.4GHz 6dBi+ on 5 to 6 GHz Features : 25mm*25mm*4mm 2400MHz to 2500MHz/5150MHz to 5850MHz Pin Type Supports IEEE 802.11 Dual-band Wi-Fi systems Dual linear polarization Tuned for 70x70mm ground plane RoHS & REACH Compliant SPE-14-8-039/B/WY Page 1 of 14 1. Introduction This unique patent pending high gain, high efficiency embedded ceramic patch antenna is designed for professional Wi-Fi dual-band IEEE 802.11 applications. It is mounted via pin and double-sided adhesive. The passive patch offers stable high gain response from 4 dBi to 6dBi on the 2.4GHz band and from 5dBi to 8dBi on the 5 ~6 GHz band. Efficiency values are impressive also across the bands with on average 60%+. The WDP.25’s high gain, high efficiency performance is the perfect solution for directional dual-band WiFi application which need long range but which want to use small compact embedded antennas. The much higher gain and efficiency of the WDP.25 over smaller less efficient more omni-directional chip antennas (these typically have no more than 2dBi gain, 30% efficiencies) means it can deliver much longer range over a wide sector. Typical applications are • Access Points • Tablets • High definition high throughput video streaming routers • High data MIMO bandwidth routers • Automotive • Home and industrial in-wall WiFi automation • Drones/Quad-copters • UAV • Long range WiFi remote control applications The WDP patch antenna has two distinct linear polarizations, on the 2.4 and 5GHz bands, increasing isolation between bands. -

Development of Earth Station Receiving Antenna and Digital Filter Design Analysis for C-Band VSAT

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 3, ISSUE 6, JUNE 2014 ISSN 2277-8616 Development of Earth Station Receiving Antenna and Digital Filter Design Analysis for C-Band VSAT Su Mon Aye, Zaw Min Naing, Chaw Myat New, Hla Myo Tun Abstract: This paper describes the performance improvement of C-band VSAT receiving antenna. In this work, the gain and efficiency of C-band VSAT have been evaluated and then the reflector design is developed with the help of ICARA and MATLAB environment. The proposed design meets the good result of antenna gain and efficiency. The typical gain of prime focus parabolic reflector antenna is 30 dB to 40dB. And the efficiency is 60% to 80% with the good antenna design. By comparing with the typical values, the proposed C-band VSAT antenna design is well optimized with gain of 38dB and efficiency of 78%. In this paper, the better design with compromise gain performance of VSAT receiving parabolic antenna using ICARA software tool and the calculation of C-band downlink path loss is also described. The particular prime focus parabolic reflector antenna is applied for this application and gain of antenna, radiation pattern with far field, near field and the optimized antenna efficiency is also developed. The objective of this paper is to design the downlink receiving antenna of VSAT satellite ground segment with excellent gain and overall antenna efficiency. The filter design analysis is base on Kaiser window method and the simulation results are also presented in this paper. Index Terms: prime focus parabolic reflector antenna, satellite, efficiency, gain, path loss, VSAT. -

Design and Application of a New Planar Balun

DESIGN AND APPLICATION OF A NEW PLANAR BALUN Younes Mohamed Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Shengli Fu, Major Professor and Interim Chair of the Department of Electrical Engineering Hualiang Zhang, Co-Major Professor Hyoung Soo Kim, Committee Member Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the College of Engineering Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Mohamed, Younes. Design and Application of a New Planar Balun. Master of Science (Electrical Engineering), May 2014, 41 pp., 2 tables, 29 figures, references, 21 titles. The baluns are the key components in balanced circuits such balanced mixers, frequency multipliers, push–pull amplifiers, and antennas. Most of these applications have become more integrated which demands the baluns to be in compact size and low cost. In this thesis, a new approach about the design of planar balun is presented where the 4-port symmetrical network with one port terminated by open circuit is first analyzed by using even- and odd-mode excitations. With full design equations, the proposed balun presents perfect balanced output and good input matching and the measurement results make a good agreement with the simulations. Second, Yagi-Uda antenna is also introduced as an entry to fully understand the quasi-Yagi antenna. Both of the antennas have the same design requirements and present the radiation properties. The arrangement of the antenna’s elements and the end-fire radiation property of the antenna have been presented. Finally, the quasi-Yagi antenna is used as an application of the balun where the proposed balun is employed to feed a quasi-Yagi antenna. -

Log Periodic Antenna

TE0321 - ANTENNA & PROPAGATION LABORATORY Laboratory Manual DEPARTMENT OF TELECOMMUNICATION ENGINEERING SRM UNIVERSITY S.R.M. NAGAR, KATTANKULATHUR – 603 203. FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION ONLY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SRM UNIVERSITY Faculty of Engineering & Technology Department of Telecommunication Engineering S. No CONTENTS Page no. Introduction – antenna & Propagation 1 6 Arranging the trainer & Performing functional Checks List of Experiments 1 12 Performance analysis of Half wave dipole antenna 2 15 Performance analysis of Folded dipole antenna 3 19 Performance analysis of Loop antenna 4 23 Performance analysis of Yagi ‐Uda antenna 5 38 Performance analysis of Helix antenna 6 41 Performance analysis of Slot antenna 7 44 Performance analysis of Log periodic antenna 8 47 Performance analysis of Parabolic antenna 9 51 Radio wave propagation path loss calculations ANTENNA & PROPAGATION LAB INTRODUCTION: Antennas are a fundamental component of modern communications systems. By Definition, an antenna acts as a transducer between a guided wave in a transmission line and an electromagnetic wave in free space. Antennas demonstrate a property known as reciprocity, that is an antenna will maintain the same characteristics regardless if it is transmitting or receiving. When a signal is fed into an antenna, the antenna will emit radiation distributed in space a certain way. A graphical representation of the relative distribution of the radiated power in space is called a radiation pattern. The following is a glossary of basic antenna concepts. Antenna An antenna is a device that transmits and/or receives electromagnetic waves. Electromagnetic waves are often referred to as radio waves. Most antennas are resonant devices, which operate efficiently over a relatively narrow frequency band. -

Log Periodic Antenna (LPA)

Log Periodic Antenna (LPA) Dr. Md. Mostafizur Rahman Professor Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering (ECE) Khulna University of Engineering & Technology (KUET) Frequency Independent Antenna : may be defined as the antenna for which “the impedance and pattern (and hence the directivity) remain constant as a function of the frequency” Antenna Theory - Log-periodic Antenna The Yagi-Uda antenna is mostly used for domestic purpose. However, for commercial purpose and to tune over a range of frequencies, we need to have another antenna known as the Log-periodic antenna. A Log-periodic antenna is that whose impedance is a logarithmically periodic function of frequency. Not only this all the electrical properties undergo similar periodic variation, particularly radiation pattern, directive gain, side lobe level, beam width and beam direction. These are broadband antenna. Bandwidth of 10:1 is achieved easily and even 100:1 is feasible if the theoretical design closely approximated. Radiation pattern may be bidirectional and unidirectional of low to moderate gain. Frequency range The frequency range, in which the log-periodic antennas operate is around 30 MHz to 3GHz which belong to the VHF and UHF bands. Construction & Working of Log-periodic Antenna The construction and operation of a log-periodic antenna is similar to that of a Yagi-Uda antenna. The main advantage of this antenna is that it exhibits constant characteristics over a desired frequency range of operation. It has the same radiation resistance and therefore the same SWR. The gain and front-to-back ratio are also the same. The image shows a log-periodic antenna. -

LECTURE 11: Loop Antennas (Radiation Parameters of a Small Loop

LECTURE 11: Loop Antennas (Radiation parameters of a small loop. A circular loop of constant current. Equivalent circuit of the loop antenna. The small loop as a receiving antenna. Ferrite loops.) Introduction Loop antennas form another antenna type, which features simplicity, low cost and versatility. Loop antennas can have various shapes: circular, triangular, square, elliptical, etc. They are widely used in applications up to the microwave bands (up to ≈ 3 GHz). In fact, they are often used as electromagnetic (EM) field probes in the microwave bands, too. Loop antennas are usually classified as electrically small (0.1C < λ ) and electrically large (C ∼ λ ). Electrically small loops of single turn have very small radiation resistance (comparable to their loss resistance). Their radiation resistance though can be substantially improved by adding more turns. Multi-turn loops have better radiation resistance but their efficiency is still very poor. That is why they are used predominantly as receiving antennas, where losses are not so important. The radiation characteristics of a small loop antenna can be additionally improved by inserting a ferromagnetic core. Radio-receivers of AM broadcast are usually equipped with ferrite-loop antennas. Such antennas are widely used in pagers, too. The small loops, regardless of their shape, have a far-field pattern very similar to that of a small dipole (normal to the plane of the loop), which is to be expected because of the equivalence of a magnetic dipole and a small current loop. Of course, the field polarization is orthogonal to that of a dipole. As the circumference of the loop increases, the pattern maximum shifts towards the loop’s normal, and when C ≈ λ , the maximum of the pattern is at the loop’s normal. -

3.1Loop Antennas All Antennas Used Radiating Elements That Were Linear Conductors

SECX1029 ANTENNAS AND WAVE PROPAGATION UNIT III SPECIAL PURPOSE ANTENNAS PREPARED BY: MS.L.MAGTHELIN THERASE 3.1Loop Antennas All antennas used radiating elements that were linear conductors. It is also possible to make antennas from conductors formed into closed loops. Thereare two broad categories of loop antennas: 1. Small loops which contain no morethan 0.086λ wavelength,s of wire 2. Large loops, which contain approximately 1 wavelength of wire. Loop antennas have the same desirable characteristics as dipoles and monopoles in that they areinexpensive and simple to construct. Loop antennas come in a variety of shapes (circular,rectangular, elliptical, etc.) but the fundamental characteristics of the loop antenna radiationpattern (far field) are largely independent of the loop shape.Just as the electrical length of the dipoles and monopoles effect the efficiency of these antennas,the electrical size of the loop (circumference) determines the efficiency of the loop antenna.Loop antennas are usually classified as either electrically small or electrically large based on thecircumference of the loop. electrically small loop = circumference λ/10 electrically large loop - circumference λ The electrically small loop antenna is the dual antenna to the electrically short dipole antenna. That is, the far-field electric field of a small loop antenna isidentical to the far-field magnetic Page 1 of 17 SECX1029 ANTENNAS AND WAVE PROPAGATION UNIT III SPECIAL PURPOSE ANTENNAS PREPARED BY: MS.L.MAGTHELIN THERASE field of the short dipole antenna and the far-field magneticfield of a small loop antenna is identical to the far-field electric field of the short dipole antenna. -

ANTENNA INTRODUCTION / BASICS Rules of Thumb

ANTENNA INTRODUCTION / BASICS Rules of Thumb: 1. The Gain of an antenna with losses is given by: Where BW are the elev & az another is: 2 and N 4B0A 0 ' Efficiency beamwidths in degrees. G • Where For approximating an antenna pattern with: 2 A ' Physical aperture area ' X 0 8 G (1) A rectangle; X'41253,0 '0.7 ' BW BW typical 8 wavelength N 2 ' ' (2) An ellipsoid; X 52525,0typical 0.55 2. Gain of rectangular X-Band Aperture G = 1.4 LW Where: Length (L) and Width (W) are in cm 3. Gain of Circular X-Band Aperture 3 dB Beamwidth G = d20 Where: d = antenna diameter in cm 0 = aperture efficiency .5 power 4. Gain of an isotropic antenna radiating in a uniform spherical pattern is one (0 dB). .707 voltage 5. Antenna with a 20 degree beamwidth has a 20 dB gain. 6. 3 dB beamwidth is approximately equal to the angle from the peak of the power to Peak power Antenna the first null (see figure at right). to first null Radiation Pattern 708 7. Parabolic Antenna Beamwidth: BW ' d Where: BW = antenna beamwidth; 8 = wavelength; d = antenna diameter. The antenna equations which follow relate to Figure 1 as a typical antenna. In Figure 1, BWN is the azimuth beamwidth and BW2 is the elevation beamwidth. Beamwidth is normally measured at the half-power or -3 dB point of the main lobe unless otherwise specified. See Glossary. The gain or directivity of an antenna is the ratio of the radiation BWN BW2 intensity in a given direction to the radiation intensity averaged over Azimuth and Elevation Beamwidths all directions. -

Antenna Characteristics Page 1

Antenna Characteristics Page 1 Antenna Characteristics 1 Radiation Pattern The radiation pattern of an antenna is a graphical representation of the radiation properties of the antenna. Graphically, we surround the antenna by a sphere and evaluate the electric / magnetic fields (far field radiation fields) at a distance equal to the radius of the sphere. Figure 1: Radiated fields evaluated on an imaginary sphere surrounding a dipole [1] Usually we will focus on one field component (Eff or Hff ) radiated by the antenna. Usually we plot the dominant component of the E-field (e.g. Eθ for a dipole). This can be done by plotting the field component over all angles (θ; φ), yielding a 3D plot. For a dipole, this leads to the doughnut pattern in 3D because of the dependence of Eθ on sin θ. Figure 2: 3D radiation pattern of an ideal dipole [1] Usually, it is easier and more meaningful to plot a field in a number of principal planes in 2D in a polar plot. A plane containing the electric field vector is called the E-plane of the antenna. For a dipole, φ = constant is the E-plane; the constant can be any angle since there is no field variation with φ. The corresponding plot is a cross section of the doughnut: Similarly, a plane containing the H vector is called the H-plane. For the dipole, θ = 90◦ is appropriate: Prof. Sean Victor Hum Radio and Microwave Wireless Systems Antenna Characteristics Page 2 Figure 3: Radiation pattern of a dipole in the E-plane (polar form) [1] Figure 4: Radiation pattern of a dipole in the H-plane (polar form) [1] Since there is no variation of the radiated E/H fields with azimuth angle (φ), we call this type of antenna pattern omnidirectional 1.