Defining Community Art : Theoretical and Practical Reconstruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^ e w rite r free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnation Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Aibor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE INFUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICAN ART FROM EIGHTEEN-EIGHTY TO THE EARLY NINETEEN-NINETIES FOR MIDDLE AND HIGH SCHOOL ART EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ronald Wayne Claxton, B.S., M.A.E. -

I “BOYS SHOULDN't HAVE to JUST BE BOYS”: the ROLE of ART

“BOYS SHOULDN’T HAVE TO JUST BE BOYS”: THE ROLE OF ART THERAPY IN HELPING ADOLESCENT MALES TO OVERCOME HARMFUL PARADIGMS OF MASCULINITY NIA NEUMANN A Research Paper in The Department of Creative Arts Therapies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada AUGUST 2020 © NIA NEUMANN 2020 i CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This research paper prepared By: Nia Neumann Entitled: “Boys shouldn’t have to just be boys”: The role of art therapy in helping adolescent males to overcome harmful paradigms of masculinity and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Creative Arts Therapies; Art Therapy Option) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality as approved by the research advisor. Research Advisor: Heather McLaughlin, MA, RMFT, ATR-BC, ATPQ Department Chair: Guylaine Vaillancourt, PhD, MTA August 2020 ii ABSTRACT “BOYS SHOULDN’T HAVE TO JUST BE BOYS”: THE ROLE OF ART THERAPY IN HELPING ADOLESCENT MALES TO OVERCOME HARMFUL PARADIGMS OF MASCULINITY NIA NEUMANN Studies of masculinity and its construction have been the subject of gender studies for decades; however, perspectives on its nature and value are evolving. Masculine denotes a particular and celebrated way of being in the world for boys, and is perpetuated through institutions, families, peers and the media. But what about those individuals who identify as male and do not represent stereotypical qualities of masculinity? How does this incongruence complicate their sense of identity or authenticity, and affect their relationships with others? The common trope “boys will be boys” has reverberated through Western society, dismissing male behavior as a simple and harmless inevitability of biology. -

Mick Jagger © Felix Aeppli 04-2020 / 09-2021

Memo From Turner Mick Jagger © Felix Aeppli 04-2020 / 09-2021 1001 July 26, 1943 Born in Dartford, Kent: Michael Philip Jagger. 1001A Late 1961 Bob Beckwith’s home, Bexleyheath, near Dartford, and/or Dick Taylor’s home, Dartford, Kent: LITTLE BOY BLUE AND THE BLUE BOYS, SOME OLD SONGS (Download EP, Promotone / iTunes, May 27, 2013: cuts 1-6, 8 [1, 4, 5 plus repeats of 2, 3 all incomplete]); THE ROLLING STONES FILES 1961-1964 (BT CD: cuts 1-6, 8 [1, 4, 5 plus repeats of 2, 3 all incomplete]); THE ROLLING STONES, REELIN’ & ROCKIN’ (BT CD: cuts 1-5 [all incomplete]); DOWN THE ROAD APIECE (STONES TOURING HISTORY VOL. 1) (BT CD: cuts 1, 9 [1 longer, but still incomplete]); HOW BRITAIN GOT THE BLUES (BT CD: cuts 2, 3, 6, 8), BILL WYMAN’S BLACK BOX (BT CD [VGP]: cuts 2, 3, 6, 8); GENUINE BLACK BOX (BT CD box set [Disc 1]: cuts 5, 11-13); REEL TIME TRIP (BT CD: cut 7): 1. Around And Around, 2. Little Queenie, 3. Beautiful Delilah (all Berry), 4. La Bamba (Trad. arr. Valens), 5. Go On To School (Reed) [not Wee Baby Blues (Turner, John- son)], 6. I Ain’t Got You (Carter), 7. I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone (Kesler, Taylor), 8. Down The Road Apiece (Raye), 9. Don’t Stay Out All Night (Arnold), 10. I Ain’t Got You (Carter), 11. Johnny B. Goode, 12. Little Queenie, 13. Beautiful Delilah (all Berry) MJ: vocals; Keith Richards: guitar, Bob Beckwith: guitar, and maybe harmonica (13); Dick Taylor: bass, guitar, drums (probably 13); Alan Etherington: maracas, drums, back-up vocals; – NOTES: Cuts 1-13: 30 minutes reel-to-reel tape of which the original was bought by Mick Jagger at Christie’s auction house, London, May 25, 1995, for £ 50,250; Cut 10: Existence unconfirmed; Cuts 11-13: Might come from a January, 1962, session at Dick Taylor’s home; – In spite of respective rumours, LITTLE BOY BLUE AND THE BLUE BOYS just rehearsed in their parents homes and never had a public appearance. -

Biographies of the Speakers in Order of Appearance

International Conference MYSORE MODERNITY, ARTISTIC NATIONALISM & THE ART OF K VENKATAPPA 25 26 27 November 2016 Venkatappa Art Gallery & NGMA Bengaluru Biographies of the Speakers In Order of Appearance ABHISHEK HAZRA is a visual artist whose close yet idiosyncratic study of the historiography of science has led him to explore various practices of knowledge production and dispersion. Hazra uses text, video, online interventions, performance and prints that often draw from speculative scenarios. Abhishek has exhibited widely including Science Gallery, Dublin, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bose Pacia, New York, MAXXI Museum, Rome, Kiran Nadar Museum, Delhi, and OCAD, Toronto. He has been an artist-in-residence in various prominent residences including Gasworks, London, Art Omi, New York and SymbioticA, Centre of Excellence in Biological Arts, Perth. Abhishek has been the recipient of multiple awards including the 2011 Sanskriti Award for Visual Art. He is currently a faculty at the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. PARTHA MITTER (Honorary D.Lit. Courtauld Institute, London), is Emeritus Professor Art History, University of Sussex. He has been a Junior Research Fellow, Churchill College, Cambridge, Open Research Fellow of Clare Hall, Cambridge; Mellon Fellow, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton; Member, Getty Research Institute LA; Fellow, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass, Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; He was also Radhakrishnan Memorial Lecturer at All Souls College, Oxford. Books include Much Maligned Monsters: History of European Reactions to Indian Art, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1977; Art and Nationalism in Colonial India 1850-1922, Cambridge University Press, 1994, Indian Art, Oxford University Press, 2002; The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant-Garde 1922-1947, Reaktion Books 2007. -

Lafa M Baskbl 2012 13 Misc

2012-2013 2012-2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION OPPONENTS Quick Facts ................................... 2 Media Policies ................................ 3 2012-13 Non-Conference GoLeopards.com Audio .................... 4 Opponents ............................ 47-49 Lafayette on Television ................... 5 2012-13 Patriot League Traveling to Lafayette ..................... 6 Opponents ............................ 49-50 Overall Series Records ....................51 2012-13 SEASON Patriot League Composite Schedule ..52 2012-13 LAFAYETTE The Patriot League ........................54 MEn’S BASKETBALL Season Outlook .............................. 8 MEDIA GUIDE TV/Radio Lineup ...........................12 2011-12 SEASON REVIEW The 2012-13 Lafayette Men’s 2012-13 Rosters ............................13 Basketball Media Guide is a Levi Giese ....................................14 Season In Review ..........................56 production of the Lafayette Tony Johnson ...............................16 Game By Game Recaps .............. 57-64 College Athletic Communications Statistics .....................................65 and Promotions Office. It was Jack Detmer .................................18 written and edited by Mark Les Smith .....................................20 Patriot League Standings ................66 Mohrman. Additional assistance provided by Phil LaBella, Scott Alan Flannigan .............................22 Morse, Brian Ludrof, Matt Panto, Seth Hinrichs ................................23 TRADITION Chris Cordero, -

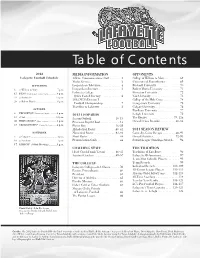

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 2012 MEDIA INFORMATION OPPONENTS Lafayette Football Schedule Athletic Communications Staff ....... 2 College of William & Mary ......... 68 Media Services ................... 3 University of Pennsylvania ......... 69 SEPTEMBER Leopards on Television ............. 4 Bucknell University ............... 70 8 at William & Mary ..............................7 p.m. Leopards on Internet............... 5 Robert Morris University........... 71 15 PENN (Student Appreciation Night) ...........6 p.m. Lafayette College Princeton University .............. 72 22 at Bucknell* .....................................12 p.m. Quick Facts/Directory............. 6 Yale University .................. 73 2012 NCAA Division I College of the Holy Cross .......... 74 29 at Robert Morris .................................6 p.m. Football Championship............ 7 Georgetown University ............ 75 Traveling to Lafayette.............. 8 Colgate University................ 76 OCTOBER Fordham University .............. 77 6 PRINCETON (Community Night) ..........6 p.m. 2012 LEOPARDS Lehigh University ................ 78 13 at Yale ..............................................12 p.m. Season Outlook ................10-15 The Rivalry................. 79, 124 20 HOLY CROSS* (Homecoming) ...........1 p.m. Preseason Depth Chart ............ 14 Overall Series Records...........80-84 27 GEORGETOWN* (Family Weekend) .....6 p.m. Player Bios ...................16-39 Alphabetical Roster .............40-41 2011 SEASON REVIEW NOVEMBER Numerical Roster ..............42-43 -

CURRICULUM VITAE Revised September 2011

CURRICULUM VITAE Revised September 2011 ADRIAN MARGARET SMITH PIPER Born 20 September 1948, New York City TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Educational Record ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Languages...................................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Philosophy Dissertation Topic.................................................................................................................. 2 4. Areas of Special Competence in Philosophy ......................................................................................... 2 5. Other Areas of Research Interest in Philosophy ................................................................................... 2 6. Teaching Experience ................................................................................................................................... 2 7. Fellowships and Awards in Philosophy................................................................................................. 3 8. Professional Philosophical Associations................................................................................................. 4 9. Service to the Profession of Philosophy.................................................................................................. 4 10. Invited Papers and Conferences in Philosophy ................................................................................. -

LM0320 Kirby-Fredendall-Profile Lores.Pdf

Morning Sun Far Shore, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches Nature Study Pennsylvania-based artist KIRBY FREDENDALL paints modernist landscapes that seek to engender the feelings of introspection and calm she experiences in the outdoors. BY JASON EDWARD KAUFMAN 192 LUXURY MAGAZINE SPRING 2020 LUXURY MAGAZINE SPRING 2020 193 irby Fredendall enjoyed painting She paints in the second floor of the building of abstraction and impressionism conveys as a child but never imagined and uses the ground floor as a showcase fleeting effects of light, seasons, and a career as an artist. Even still, for her works, mainly oil paintings of weather in a way that really lets you feel the writing was on the wall. She lakeside scenes. the scene. Her recording of these peaceful grew up on the western bank of Fredendall earned a B.A. in art history moments of reverie and delight in a solitary Kthe Delaware River, in a rural region known from Duke University in 1988, and after encounter with nature has struck a chord as Bucks County, Pennsylvania. It was here, a course at Le Cordon Bleu in London, with her audience. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, returned home to work as a pastry chef. Then Fredendall’s artworks have been presented that the Pennsylvania impressionists took she befriended a group of art students from in numerous group and solo shows, mainly up residence in inexpensive farmhouses and the University of Pennsylvania and began in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and she has disused industrial properties. They set about making abstract paintings, some of which had a one-artist exhibition at the Michener painting sylvan fields and rustic scenes along were exhibited and sold locally. -

An Ethnographic Exploration of Visual Sovereignty and Contemporary Native American Art

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 2020 Framing Representation: An Ethnographic Exploration of Visual Sovereignty and Contemporary Native American Art Laura A. Hughes University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Laura A., "Framing Representation: An Ethnographic Exploration of Visual Sovereignty and Contemporary Native American Art" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1782. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1782 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Framing Representation: An Ethnographic Exploration of Visual Sovereignty and Contemporary Native American Art ______________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences University of Denver ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________ by Laura A. Hughes August 2020 Advisor: Dr. Christina Kreps ©Copyright by Laura A. Hughes 2020 All Rights Reserved Author: Laura A. Hughes Title: Framing Representation: An Ethnographic Exploration of Visual Sovereignty and Contemporary Native American Art Advisor: Dr. Christina Kreps Degree Date: August 2020 Abstract The nature of this research is to explore the idea of visual sovereignty within contemporary Native American art, and how this concept engages with practices of decolonization. Through conducting semi-structured interviews with five artists who self- identify as Native American, I explore how the artists engage with this concept, what visual narratives their artwork presents, and how their works function as acts of decolonization. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Jeffrey F. Hamburger

CURRICULUM VITAE Jeffrey F. Hamburger (revised January 1, 2020) BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION/ADDRESS Born 2.19.1957, London, United Kingdom (U.S. citizen from birth) Dept. of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Sackler Museum 485 Broadway Cambridge MA 02138 USA Dept. Phone: 617 495–2377 Office Phone/Voice Mail: 617 495–8732 Fax: 617 495–1769 Email: [email protected] Home address 46 Orchard St. Belmont MA 02478 EDUCATION: Ph.D., 1987, Department of the History of Art, Yale University “The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland ca. 1300,” supervisor, Prof. Walter Cahn, awarded the Francis Blanshard Prize for “the outstanding doctoral dissertation submitted to the History of Art Department,” and the Theron Rockwell Field Prize for an “outstanding “poetic, literary or religious work” in the Humanities. M.A., 1982, Department of the History of Art, Yale University. B.A, 1979, Yale College, Summa cum laude. Warren Scholarship, for the graduating senior with the highest academic standing in the Humanities. Mark Dietz Memorial Prize, for original research in the History of Art. Tinker Prize, for the outstanding senior in the English department. Bergin Cup, for achievement in the Humanities. Distinction in the History of Art; Distinction in English; Phi Beta Kappa, 1977. EMPLOYMENT: Harvard University, Dept. of History of Art and Architecture, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Culture, 2008–; Full Professor, 2000–2007 University of Toronto, Dept. of History of Art, Full Professor, 1998–, Associate Professor, 1997–1998 Oberlin College, Irving E. Houck (Associate) Professor in the Humanities, 1992–1997; Associate Professor with tenure, 1991–1992; Assistant Professor, 1987–1991; Instructor, 1986–1987. -

Bogdan Achimescu Matilda Aslizadeh Rebecca Belmore Jake & Dinos

Bogdan Achimescu Matilda Aslizadeh Rebecca Belmore Jake & Dinos Chapman Dana Claxton Douglas Coupland Jeremy Deller Mario Doucette David Garneau William Kentridge Fawad Khan 1 Wanda Koop Emanuel Licha Shirin Neshat Michael Patterson-Carver Dan Perjovschi Raymond Pettibon Nancy Spero Althea Thauberger Jason Thiry Scott Waters Balint Zsako Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina, SK Part I: July 17 – August 30, 2009 Part II: September 4 – October 18, 2009 Galerie de l’UQAM, Montreal, QC January 15 – February 13, 2010 The Military Museums, Calgary, AB July 22 – October 2, 2011 curated by Amanda Cachia. essays by Dick Averns, Amanda Cachia, Randal Rogers and Sunera Thobani, with an Introduction by Amanda Cachia, and Forewords by Louise Déry and Tom Doucette. Contents Contenu introduction Amanda Cachia, Director/Curator Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina, SK 6 préface 8 Amanda Cachia, Directrice/Commissaire d’exposition forewords Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina, SK Louise Déry, Director, Galerie de l’UQAM, Montreal, QC 10 Tom Doucette, Director, The Military Museums, Calgary, AB 12 avant-propos 11 Louise Déry, Directrice, Galerie de l’UQAM, Montreal, QC curator’s acknowledgements 14 13 Tom Doucette, Directeur Exécutif, The Military Museums, Calgary, AB 4 Map of Blood 18 16 les remerciements de la commissaire 5 Amanda Cachia 32 Carte de sang In Deference to a New Diabolique 48 Amanda Cachia Dick Averns 56 Eu Égard à un Nouveau Diabolique Everyday Violence and Violence, Everyday 62 Dick Averns Randal Rogers 69 La Violence Quotidienne et la Violence au Quotidien Race and the Art of War 75 Randal Rogers Sunera Thobani 81 La Race et L’Art De la Guerre artist biographies 87 Sunera Thobani writer biographies 152 87 biographies des artistes list of works 155 152 biographies des auteurs 155 liste des œuvres INTRODUCTION too much for the more liberal-minded. -

Curriculum Vitae

DOMENICO DE CLARIO – CURRICULUM VITAE Domenico de Clario was born in Trieste, Italy, in 1947 and migrated to Australia with his family in 1956. EDUCATION 1966-69 Bachelor of Architecture, Bachelor of Town Planning, Melbourne University 1967-68 Painting Diploma, Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milan, Italy 1968 Lithography Diploma, Accademia di Belle Arti di Urbino, Italy 1973-75 Diploma of Art, Preston Institute of Technology, Melbourne 1996-98 Master of Arts, Victoria University, Faculty of Human Movement 1998-2001 PhD, Performance Studies, Faculty of Human Movement, Victoria University, Melbourne ACADEMIC POSITIONS/EMPLOYMENT 1973-1996 Undergraduate and postgraduate teaching, supervision and administration at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology 1996-1998 Teaching Performance Studies, Victoria University; teaching at VCA (Centre for Ideas) 2001-2006 Head of the School of Contemporary Art and Associate Dean, Research and Development, Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts, Edith Cowan University, Perth, West Australia. 2006-2009 Head of Department of Fine Arts, Faculty of Art, Architecture and Design, Monash University, Melbourne. 2009-2012 Artistic and Managing Director, Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide. 2010- Adjunct Professor, School of Art, Design and Architecture, University of South Australia, Adelaide 2014 – Chair, Mildura Palimpsest Biennale Committee 2016 – Chair, Arts Mildura 2016 – Co-ordinator, museum of innocence mildura AWARDS AND RESIDENCIES 2015 Creative Victoria, Artists in Schools Grant: