2012 Updated Consensus Guidelines for Managing Abnormal Cervical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developmental Abnormalities Easy to Misdiagnose

8 Gynecology O B .GYN. NEWS • March 15, 2005 Developmental Abnormalities Easy to Misdiagnose BY JANE SALODOF MACNEIL inappropriate surgery, according to Dr. even an entity called obstructed hemi- Abnormalities of the vulva include con- Contributing Writer Zurawin, chief of the section of pediatric vagina.” genital labial fusion, which he said could and adolescent gynecology at Baylor and Clitoral hypertrophy is the only devel- be corrected with a simple flap proce- H OUSTON — Developmental abnor- of the gynecology service at Texas Chil- opmental abnormality of the clitoris, ac- dure. Surgery is rarely used, however, for malities of the vulva and vagina are often dren’s Hospital in Houston. cording to Dr. Zurawin. It used to be acquired labial agglutination. “This is one easy to correct, but also easy to misdiag- “You need to be familiar with the syn- treated by clitoridectomy with “very un- of most common referrals from pediatri- nose, Robert K. Zurawin, M.D., warned at dromes before you treat. Many people satisfactory results,” he said, describing cians, because they don’t know what to do a conference on vulvovaginal diseases are confronted with these conditions, and more conservative procedures in use to- with it and they are afraid,” Dr. Zurawin sponsored by Baylor College of Medicine. they don’t know what they really are,” he day. “This is mainly a cosmetic problem said. Many physicians have not been trained said. “With the obstructions, for example, for patients, and the surgical management He attributed most cases to diaper rash, to recognize these rare disorders and, as a they may just think it is an imperforate hy- is resection of the enlarged clitoris,” he bubble baths, and detergents that can in- result, run the risk of doing excessive or men and are not even aware that there is said. -

2021 – the Following CPT Codes Are Approved for Billing Through Women’S Way

WHAT’S COVERED – 2021 Women’s Way CPT Code Medicare Part B Rate List Effective January 1, 2021 For questions, call the Women’s Way State Office 800-280-5512 or 701-328-2389 • CPT codes that are specifically not covered are 77061, 77062 and 87623 • Reimbursement for treatment services is not allowed. (See note on page 8). • CPT code 99201 has been removed from What’s Covered List • New CPT codes are in bold font. 2021 – The following CPT codes are approved for billing through Women’s Way. Description of Services CPT $ Rate Office Visits New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; straightforward decision making; 15-29 minutes 99202 72.19 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; low level decision making; 30-44 minutes 99203 110.77 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; moderate level decision making; 45-59 minutes 99204 165.36 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; high level decision making; 60-74 minutes. 99205 218.21 Established patient; evaluation and management, may not require presence of physician; 99211 22.83 presenting problems are minimal Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, straightforward decision making; 10-19 99212 55.88 minutes Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, low level decision making; 20-29 minutes 99213 90.48 Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, moderate level decision making; 30-39 99214 128.42 minutes Established patient; comprehensive history exam, high complex decision making; 40-54 minutes 99215 128.42 Initial comprehensive -

Agreement Between Endocervical Brush and Endocervical Curettage in Patients Undergoing Repeat Endocervical Sampling

Agreement Between Endocervical Brush and Endocervical Curettage in Patients Undergoing Repeat Endocervical Sampling Meredith J. Alston MD David W. Doo MD Sara E. Mazzoni MD MPH Elaine H. Stickrath MD Denver Health Medical Center University of Colorado Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Background • Women with abnormal Pap tests referred for colposcopy frequently require sampling of the endocervix • ASCCP deems both the endocervical brush (ECB) and the endocervical currette (ECC) appropriate means of collecting endocervical samples (1) • Both have advantages and disadvantages, and it is unclear if one modality is superior Background • ECB has good sensitivity for endocervical lesions, it has poor specificity, ranging from 26- 38%2,3 • ECC has an excellent negative predictive value of 99.4% in women who had a satisfactory colposcopy • ECB is better tolerated by the patient, but runs the risk of contamination from the ectocervix • ECC is less likely to obtain an adequate sample Background • The results from the endocervical sample may influence clinical management after colposcopy. • Certain treatment options for high grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia are available only to women with negative endocervical sampling. ▫ Ablative techniques ▫ Expectant management Background • Over concerns related to potential complications of excisional treatments, as well as over- treatment, there has been a push to re-introduce ablative techniques and, in appropriate clinical circumstances, expectant management, into the routine treatment of patients with cervical cancer precursors (12). Background • At our institution, it is our concern that due to the possibility of contamination from the ectocervix, a positive ECB may not represent a true positive endocervical sample. • We do not use a sleeve • Positive ECBs return for ECC if otherwise a candidate for ablative therapy or expectant management Objective • To describe the agreement between these two modalities of endocervical sampling. -

Colposcopy.Pdf

CCololppooscoscoppyy ► Chris DeSimone, M.D. ► Gynecologic Oncology ► Images from Colposcopy Cervical Pathology, 3rd Ed., 1998 HistoHistorryy ► ColColpposcopyoscopy wwasas ppiioneeredoneered inin GGeermrmaanyny bbyy DrDr.. HinselmannHinselmann dduriurinngg tthhee 19201920’s’s ► HeHe sousougghtht ttoo prprooveve ththaatt micmicrroscopicoscopic eexaminxaminaationtion ofof thethe cervixcervix wouwoulldd detectdetect cervicalcervical ccancanceerr eeararlliierer tthhaann 44 ccmm ► HisHis workwork identidentiifiefiedd severalseveral atatyypicalpical appeappeararanancceses whwhicichh araree stistillll usedused ttooddaay:y: . Luekoplakia . Punctation . Felderung (mosaicism) Colposcopy Cervical Pathology 3rd Ed. 1998 HistoHistorryy ► ThrThrooughugh thethe 3030’s’s aanndd 4040’s’s brbreaeaktkthrhrouougghshs wwereere mamaddee regregaarrddinging whwhicichh aapppepeararancanceess wweerere moremore liklikelelyy toto prprogogressress toto invinvaasivesive ccaarcinomrcinomaa;; HHOOWEWEVVERER,, ► TheThessee ffiinndingsdings wweerere didifffficiculultt toto inteinterrpretpret sincesince theythey werweree notnot corcorrrelatedelated wwithith histologhistologyy ► OneOne resreseaearcrchherer wwouldould claclaiimm hhiiss ppatatientsients wwithith XX ffindindiingsngs nevernever hahadd ccaarcinomarcinoma whwhililee aannothotheerr emphemphaatiticcallyally belibelieevedved itit diddid ► WorldWorld wiwidede colposcopycolposcopy waswas uunnderderuutitillizizeedd asas aa diadiaggnosticnostic tooltool sseeconcondadaryry ttoo tthheseese discrepadiscrepannciescies HistoHistorryy -

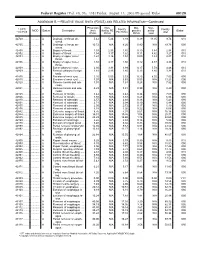

RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) and RELATED INFORMATION—Continued

Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 158 / Friday, August 15, 2003 / Proposed Rules 49129 ADDENDUM B.—RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) AND RELATED INFORMATION—Continued Physician Non- Mal- Non- 1 CPT/ Facility Facility 2 MOD Status Description work facility PE practice acility Global HCPCS RVUs RVUs PE RVUs RVUs total total 42720 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 5.42 5.24 3.93 0.39 11.05 9.74 010 scess. 42725 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 10.72 N/A 8.26 0.80 N/A 19.78 090 scess. 42800 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.39 2.35 1.45 0.10 3.84 2.94 010 42802 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.54 3.17 1.62 0.11 4.82 3.27 010 42804 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.24 3.16 1.54 0.09 4.49 2.87 010 throat. 42806 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.58 3.17 1.66 0.12 4.87 3.36 010 throat. 42808 ....... ........... A Excise pharynx lesion ...... 2.30 3.31 1.99 0.17 5.78 4.46 010 42809 ....... ........... A Remove pharynx foreign 1.81 2.46 1.40 0.13 4.40 3.34 010 body. 42810 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 3.25 5.05 3.53 0.25 8.55 7.03 090 42815 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 7.07 N/A 5.63 0.53 N/A 13.23 090 42820 ....... ........... A Remove tonsils and ade- 3.91 N/A 3.63 0.28 N/A 7.82 090 noids. -

Diagnostic Tests for Vaginosis/Vaginitis

Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Diagnostic tests for vaginosis/vaginitis Christa Harstall and Paula Corabian October 1998 HTA12 Diagnostic tests for vaginosis/vaginitis Christa Harstall and Paula Corabian October 1998 © Copyight Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 1998 This Health Technology Assessment Report has been prepared on the basis of available information of which the Foundation is aware from public literature and expert opinion, and attempts to be current to the date of publication. The report has been externally reviewed. Additional information and comments relative to the Report are welcome, and should be sent to: Director, Health Technology Assessment Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research 3125 Manulife Place, 10180 - 101 Street Edmonton Alberta T5J 3S4 CANADA Tel: 403-423-5727, Fax: 403-429-3509 This study is based, in part, on data provided by Alberta Health. The interpretation of the data in the report is that of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the Government of Alberta. ISBN 1-896956-15-7 Alberta's health technology assessment program has been established under the Health Research Collaboration Agreement between the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research and the Alberta Health Ministry. Acknowledgements The Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research is most grateful to the following persons for their comments on the draft report and for provision of information. The views expressed in the final report are those of the Foundation. Dr. Jane Ballantine, Section of General Practice, Calgary Dr. Deirdre L. Church, Microbiology, Calgary Laboratory Services, Calgary Dr. Nestor N. Demianczuk, Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton Dr. -

Key Points: • a Pap Test and Pelvic Exam Are Important Parts of A

Key Points: • A Pap test and pelvic exam are important parts of a woman’s routine health care because they can detect cancer or abnormalities that may lead to cancer of the cervix (see Question 3). • Women should have a Pap test at least once every three years, beginning about three years after they begin to have sexual intercourse, but no later than age 21 (see Question 6). • If the Pap test shows abnormalities, further tests an/or treatment may be necessary (see Question 11). • Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the primary risk factor for cervical cancer (see Question 13). 1. What is a Pap test? The Pap test (sometimes called a Pap smear) is a way to examine cells collected from the cervix (the lower, narrow end of the uterus). The main purpose of the Pap test is to find abnormal cell changes that may arise from cervical cancer or before cancer develops. 2. What is a pelvic exam? In a pelvic exam, the uterus, vagina, ovaries, fallopian tubes, bladder, and rectum are felt to find any abnormality in their shape or size. During a pelvic exam, an instrument called a speculum is used to widen the vagina so that the upper portion of the vagina and the cervix can be seen. 3. Why are a Pap test and pelvic exam important? A Pap test and pelvic exam are important parts of a woman’s routine health care because they can detect abnormalities that may lead to invasive cancer of the cervix. These abnormalities can be treated before cancer develops. -

Obstetrics and Gyneclogy

3/28/2016 Obstetrics and Gynecology Presented by: Peggy Stilley, CPC, CPC-I, CPMA, CPB, COBGC Objectives • Procedures • Pregnancy • Payments • Patient Relationships 1 3/28/2016 Female Genital Anatomy Terminology and Abbreviations • Endometriosis • Neoplasm • BUS • TAH/BSO • G3P2 2 3/28/2016 Procedures • Hysterectomy • Prolapse repairs • IUDs • Colposcopy Hysterectomy • Approach • Open • Vaginal • Total Laparoscopic • Laparoscopic assisted • Extent • Total • Subtotal • Supracervical • Diagnosis 3 3/28/2016 CPT Codes • Abdominal 58150 – • With or without removal tubes/ovaries 58240 • Some additional services • Vaginal 58260-58270 • Size of uterus < 250 grams, > 250 grams 58275-58294 • Additional services CPT Codes • LAVH 58541-58544 • Detach uterus , cervix, and structures through the scope 58548-58554 • Uterus removed thru the vagina • TLH • Detach structures laparoscopically entire 58570- 58573 uterus, cervix, bodies • Removed thru the vagina or abdomen • LSH • Detaching structures through the scope, 58541 – 58544 leaving the cervix • Morcellating – removing abdominally 4 3/28/2016 Hysterectomy Additional procedures performed • Tubes & Ovaries removed • Enterocele repair • Repairs for incontinence • Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz • Colporrhaphy • Colpo-urethropexy • Urethral Sling • TVT, TOT 5 3/28/2016 Procedures • 57288 Sling • 57240 Anterior Repair • 57250 Posterior Repair • +57267 Add on code for mesh/graft • 57260 Combo of A&P • 57425 Laparoscopic Colpopexy • 57280 Colpopexy, Abdominal approach • 57282 Colpopexy, vaginal approach Example 1 PREOPERATIVE DIAGNOSES: 1. Menorrhagia unresponsive to medical treatment with resulting chronic blood loss anemia POSTOPERATIVE DIAGNOSES: 1. Menorrhagia 2. Blood loss anemia TITLE OF SURGERY: Total abdominal hysterectomy ANESTHESIA: GENERAL ENDOTRACHEAL ANESTHESIA. INDICATIONS: The patient is a lovely 52-year-old female who presented with menorrhagia that is non- responsive to medical treatment. -

The Relationship Between Female Genital Aesthetic Perceptions and Gynecological Care

Examining the Vulva: The Relationship between Female Genital Aesthetic Perceptions and Gynecological Care By Vanessa R. Schick B.A. May 2004, University of Massachusetts, Amherst A Dissertation Submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2010 Dissertation directed by Alyssa N. Zucker Associate Professor of Psychology and Women’s Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Vanessa R. Schick has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 19, 2009. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Examining the Vulva: The Relationship between Female Genital Aesthetic Perceptions and Gynecological Care Vanessa R. Schick Dissertation Research Committee: Alyssa N. Zucker, Associate Professor of Psychology & Women's Studies, Dissertation Director Laina Bay-Cheng, Assistant Professor of Social Work, University at Buffalo, Committee Member Maria-Cecilia Zea, Professor of Psychology, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2009 by Vanessa R. Schick All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments The past five years have changed me and my research path in ways that I could have never imagined. I feel incredibly fortunate for my mentors, colleagues, friends and family who have supported me throughout this journey. First, I would like to start by expressing my sincere appreciation to my phenomenal dissertation committee and all those who made this dissertation possible: Without Alyssa Zucker, my advisor, my journey would have been an entirely different one. Few advisors would allow their students to forge their own research path. -

Laboratory Test: Wet Prep Standing Order in N.C

Laboratory Test: Wet Prep Standing Order in N.C. Board of Nursing Format INSTRUCTIONS FOR LOCAL HEALTH DEPARTMENT STAFF ONLY Use the approved language in this standing order to create a customized standing order exclusively for your agency. Print the customized standing order on agency letterhead. Review standing order at least annually and obtain Medical Director’s signature. Standing order must include the effective start date and the expiration date. Assessment Subjective Findings The following subjective criteria meet the requirement for an STD ERRN to collect a Wet Prep by standing order: Vaginal discharge with or without foul odor Dyspareunia Dysuria New or multiple sex partner(s) Lack of condom use Reports contact to: Chlamydia (CT), Gonorrhea Asymptomatic (GC), Non-Gonococcal Urethritis (NGU), Pelvic Anonymous sex Inflammatory Disease (PID), Mucopurulent Cervicitis (MPC), or Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) Objective Findings If one or more of these clinical findings are present, the STD ERRN shall collect a Wet Prep by standing order: 1. vaginal discharge 2. endocervical discharge 3. foul odor 4. cervical inflammation, usually manifest as edema or easily induced cervical bleeding upon cervical swabbing 5. petechiae on cervix 6. vaginal or vulva irritation 7. warts or other abnormal growths in vagina or on cervix 8. vaginal exposure within last 60 days 9. verified contact Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, NGU, MPC or Trichomonas Plan of Care Implementation A registered nurse or STD ERRN employed or contracted by the local health department may order a Wet Prep collected by the STD ERRN or other medical provider. Nursing Actions A. Specimen Collection by STD ERRN: To collect a Wet Prep specimen: 1. -

Advanced-Pelvic-Exams1.Pdf

8/3/2014 Describe at least two techniques for performing pelvic examination with a patient who has Jacki Witt, JD, MSN, WHNP-BC, SANE-A, FAANP experienced sexual assault/abuse Caroline Hewitt, DNS, RN, NP Practice at least two new pelvic examination techniques with a standardized patient Select appropriate screening and diagnostic testing for women with specific pelvic organ symptoms Jacki Witt Watson Pharmaceuticals – Honorarium – Advisory Board Agile Pharmaceuticals – Honorarium – Advisory WHO Afaxus Pharmaceuticals – Honorarium – Advisory Committee Bayer Pharmaceuticals – Honorarium – Advisory Board WHAT WHEN Caroline Hewitt WHERE Prior to February 5, 2014 disclosures: Watson Pharmaceuticals – Honorarium-Advisory Board HOW After February 5, 2014: Nothing to disclose WHY Identify the indications for a pelvic examination -Lithotomy common in US Describe at least two techniques for performing -Some patients pelvic examination with an obese patient find it disempowering, Describe at least two techniques for performing abusive & humiliating pelvic examination with a patient who has Haar, et al 1997 signs/symptoms of decreased estrogen stimulation -Patient’s have to vaginal tissues described metal Describe at least two techniques for performing stirrups as ‘cold’ pelvic examination with a & ‘hard’; say their use developmentally/cognitively disabled person is impersonal, sterile or degrading Olson 1981 1 8/3/2014 • 197 adult women having routine cervical cytology • Patients reported less discomfort and feelings of vulnerability if: PLASTIC : direct lamp connection, • Semi-reclining vs. supine transparency facilitates visualization, • No stirrup method used audible and sensible clicks distressing and • No significant differences in quality of cyto specimen considered not ‘green’ (but study not powered to definitively look at this outcome) • Routine in UK, Australia, N. -

Pap Test That Can Turn Into Cancer Cells

F REQUENTLY A SKED Q UESTIONS infections and abnormal cervical cells Pap Test that can turn into cancer cells. Treatment can prevent most cases of cervical cancer from developing. womenshealth.gov Getting regular Pap tests is the best Q: What is a Pap test? thing you can do to prevent cervical 1-800-994-9662 A: The Pap test, also called a Pap smear, cancer. About 13,000 women in TDD: 1-888-220-5446 checks for changes in the cells of your America will find out they have cervi- cervix. The cervix is the lower part of cal cancer this year. And in 2004, 3,500 the uterus (womb) that opens into the women died from cervical cancer in the vagina (birth canal). The Pap test can United States. tell if you have an infection, abnormal (unhealthy) cervical cells, or cervical Q: Do all women need Pap tests? cancer. A: It is important for all women to have pap tests, along with pelvic exams, as part of their routine health care. You need a Pap test if you are: ● 21 years or older Fallopian tube ● under 21 years old and have been sexually active for three years or Ovaries more There is no age limit for the Pap test. Even women who have gone through menopause (when a woman’s periods Uterus stop) need regular Pap tests. (womb) Cervix Q: How often do I need to get a Pap test? Vagina A: It depends on your age and health his- tory. Talk with your doctor about what is best for you.