This Opinion Is Not a Precedent of the TTAB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Registered in England and Wales, Wholly Owned

RELATED UNDERTAKINGS In accordance with Section 409 of the Companies Act 2006 a full list of subsidiaries, partnerships, associates and joint ventures, the principal activity, the country of incorporation and the effective percentage of equity owned, as at 30 September 2017 are disclosed below. With the exception of Imperial Tobacco Holdings (2007) Limited, which is wholly owned by the Company, none of the shares in the subsidiaries is held directly by the Company. SUBSIDIARIES: REGISTERED IN ENGLAND AND WALES, WHOLLY OWNED Name Principal activity and registered address Attendfriend Limited Dormant 121 Winterstoke Road, Bristol, BS3 2LL, England British Tobacco Company Limited Dormant 121 Winterstoke Road, Bristol, BS3 2LL, England Congar International UK Limited Dormant 121 Winterstoke Road, Bristol, BS3 2LL, England Fontem UK Limited In liquidation BDO LLP, Two Snowhill, Birmingham, B4 6GA, England Imperial Brands Enterprise Finance Limited Provision of treasury services to other Group companies 121 Winterstoke Road, Bristol, BS3 2LL, England Imperial Brands Finance PLC Provision of treasury services to other Group companies 121 Winterstoke Road, Bristol, BS3 2LL, England Imperial Investments Limited Dormant 121 Winterstoke Road, Bristol, BS3 2LL, England Imperial Tobacco Altadis Limited Provision of finance to other Group companies 121 Winterstoke Road, Bristol, BS3 2LL, England Imperial Tobacco Capital Assets (1) Provision of finance to other Group companies 121 Winterstoke Road, Bristol, BS3 2LL, England Imperial Tobacco Capital Assets -

“They Twisted My Arm to Get These Deals.”

03-04_TAA_catalog.cg3 7/1/03 12:35 PM Page 1 2003/2004 2003 PIPE OF THE YEAR Erik says: AT PRICES “They twisted my arm “YOU WILL NEVER SEE AGAIN!” to get these deals.” SEE PAGE 2 03-04_TAA_catalog.cg3 7/1/03 12:35 PM Page 2 “They twisted my arm to get these No two handmade pipes The best value deals, you can’t beat these prices!” are exactly alike. on the market! EXCLUSIVE Bjarne Nielsen offers an The famous Danish pipe maker, Erik Nording, excellent pipe at a fair price. presents OCASO pipes at prices you His reputation depends on it. will never see again! Bjarne churchwarden pipes 3C 2003 Pipe of the Year are the latest rage, but all of these shapes are exquisite. 3D* 2B 3E 2C * 3F 2A 2A Nording Freehand Tall, smooth. 2C Nording Freehand Apple, with carving. 3G* Normally $200. Now only $110.00 Normally $100. Now only $59.95 2B Nording Freehand Tall, with carving. 2D Nording Freehand Apple, smooth. *FLAT Normally $100. Now only $59.95 Normally $200. Now only $110 (not shown) BOTTOM “SITTERS” 3A 3B 3H* TABLE OF CONTENTS Cigars . 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 bjarne Pipes . 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 40, 41, 48, 50 Cigarettes and Accessories . 16, 42, 43, 44, 46, 47, 48 3A Churchwarden with Carving. $65 Flasks and Barware . 49 3B Churchwarden Smooth. $79 Humidors . 10, 11 3C Bent Prince with Carving. $65 Lighters. 15, 17, 39, 51 3D Freehand Sitter with Carving. -

Actor Vince Vaughn

internet only CigarJUNE 2, 2015 n VOL. 20,Insider NO. 11 n FROM THE PUBLISHER OF CIGAR AFICIONADO MAGAZINE CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE IN THIS ISSUE: FEATURED CIGAR TASTING REPORT: MY FATHER LE BIJOU 1922 PREVIEWS FROM THE AUGUST 2015 BOX PRESS TORPEDO 93 ISSUE OF CIGAR AFICIONADO: NICARAGUA n PRICE: $11.40 n BODY: MEDIUM TO FULL POINTS n My Father Le Bijou 1922 Box Press Torpedo [page 2] For a full tasting, see page two. n Padrón Serie 1926 80 Years Maduro [page 2] n Trinidad Vigía [page 2] n Don Pepin Garcia Cuban Classic 1979 [page 2] BEST CIGARS THIS ISSUE n Por Larrañaga Picadores [page 3] n Fuente Fuente OpusX Angel’s Share Reserva d’Chateau [page 3] My Father Le Bijou 1922 Box Press Torpedo Nicaragua 93 n Partagás Serie D No. 6 [page 3] Padrón Serie 1926 80 Years Maduro Nicaragua 93 n H. Upmann Connossieur A [page 3] VERTICAL BRAND TASTINGS: Trinidad Vigía Cuba 93 n Romeo Añejo by Romeo y Julieta [page 4] Don Pepin Garcia Cuban Classic 1979 Nicaragua 92 NEW SIZES: Por Larrañaga Picadores Cuba 92 n Hoyo de Monterrey Edición de Cumpleaños 150 [page 4] Fuente Fuente OpusX Angel’s Share n Matilde Renacer Lancero [page 4] Reserva d’Chateau Dom. Rep. 92 CIGAR NEWS n The Avo Syncro Nicaragua [page 5] n El Centurion Wrapped in Connecticut [page 5] n Montecristo With a Vintage Wrapper [page 6] n Keystone State Looks to Tax Cigars [page 6] ACTOR VINCE VAUGHN n Quesada Cigars Distributes La Matilde [page 6] HE MIGHT BE KNOWN FOR COMEDY, but Vince Vaughn has a serious side, along with a n Nick Melillo Starts up Foundation [page 7] penchant for cigars. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2019

IMPERIAL BRANDS PLC BRANDS IMPERIAL ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019 ACCOUNTS AND REPORT ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019 OUR PURPOSE WE CAN I OWN Our purpose is to create something Everything See it, seize it, is possible, make it happen better for the world’s smokers with together we win our portfolio of high quality next generation and tobacco products. In doing so we are transforming WE SURPRISE I AM our business and strengthening New thinking, My contribution new actions, counts, think free, our sustainability and value creation. exceed what’s speak free, act possible with integrity OUR VALUES Our values express who we are and WE ENJOY I ENGAGE capture the behaviours we expect Thrive on Listen, challenge, share, make from everyone who works for us. make it fun connections The following table constitutes our Non-Financial Information Statement in compliance with Sections 414CA and 414CB of the Companies Act 2006. The information listed is incorporated by cross-reference. Additional Non-Financial Information is also available on our website www.imperialbrands.com. Policies and standards which Information necessary to understand our business Page Reporting requirement govern our approach1 and its impact, policy due diligence and outcomes reference Environmental matters • Occupational health, safety and Environmental targets 21 environmental policy and framework • Sustainable tobacco programme International management systems 21 Climate and energy 21 Reducing waste 19 Sustainable tobacco supply 20 Supporting wood sustainability -

Tobacco Deal Sealed Prior to Global Finance Market Going up in Smoke

marketwatch KEY DEALS Tobacco deal sealed prior to global finance market going up in smoke The global credit crunch which so rocked £5.4bn bridging loan with ABN Amro, Morgan deal. “It had become an auction involving one or Iinternational capital markets this summer Stanley, Citigroup and Lehman Brothers. more possible white knights,” he said. is likely to lead to a long tail of negotiated and In addition it is rescheduling £9.2bn of debt – Elliott said the deal would be part-funded by renegotiated deals and debt issues long into both its existing commitments and that sitting on a large-scale disposal of Rio Tinto assets worth the autumn. the balance sheet of Altadis – through a new as much as $10bn. Rio’s diamonds, gold and But the manifestation of a bad bout of the facility to be arranged by Citigroup, Royal Bank of industrial minerals businesses are now wobbles was preceded by some of the Scotland, Lehmans, Barclays and Banco Santander. reckoned to be favourites to be sold. megadeals that the equity market had been Finance Director Bob Dyrbus said: Financing the deal will be new underwritten expecting for much of the last two years. “Refinancing of the facilities is the start of a facilities provided by Royal Bank of Scotland, One such long awaited deal was the e16.2bn process that is not expected to complete until the Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse and Société takeover of Altadis by Imperial Tobacco. first quarter of the next financial year. Générale, while Deutsche and CIBC are acting as Strategically the Imps acquisition of Altadis “Imperial Tobacco only does deals that can principal advisors on the deal with the help of has been seen as the must-do in a global generate great returns for our shareholders and Credit Suisse and Rothschild. -

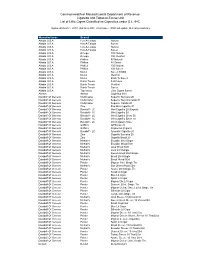

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Revenue Cigarette and Tobacco Excise Unit List of Little Cigars Classified As Cigarettes Under G.L

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Revenue Cigarette and Tobacco Excise Unit List of Little Cigars Classified as Cigarettes under G.L. 64C Updated March 1, 2010 This list is NOT all inclusive. DOR will update this list periodically. Manufacturer Brand Altadis U.S.A Hav-A-Tampa Natural Altadis U.S.A Hav-A-Tampa Sweet Altadis U.S.A Hav-A-Tampa Natural Altadis U.S.A Hav-A-Tampa Sweet Altadis U.S.A Omega 100 Natural Altadis U.S.A Omega 100 Menthol Altadis U.S.A Phillies 80 Natural Altadis U.S.A Phillies 80 Sweet Altadis U.S.A Phillies 100 Natural Altadis U.S.A Phillies 100 Sweet Altadis U.S.A Muriel Sweet 'N Mild Altadis U.S.A Muriel Menthol Altadis U.S.A Muriel Black 'N Sweet Altadis U.S.A Dutch Treats Full Flavor Altadis U.S.A Dutch Treats Menthol Altadis U.S.A Dutch Treats Sweet Altadis U.S.A Top Value Little Cigars Sweet Ashton Ashton Cigarillos Mini Davidoff Of Geneva Clubmaster Superior Sumatra 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Clubmaster Superior Sumatra Gold 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Clubmaster Superior Vanilla 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Zino Red Mini Cigarillo 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Davidoff - LC Mini Cigarillo 20 (Export) Davidoff Of Geneva Davidoff - LC Mini Cigarillo 50 Davidoff Of Geneva Davidoff - LC Mini Cigarillo Silver 50 Davidoff Of Geneva Davidoff - LC Mini Cigarillo Silver 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Davidoff - LC Mini Cigarelo Silver Davidoff Of Geneva Griffin's Griffionos 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Griffin's Cigarellos (Cigars) Davidoff Of Geneva Davidoff - LC Aromatic Cigarillo 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Zino Cigarillo Sumatra 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Zino Cigarillo Brasil 20 Davidoff Of Geneva Mehari's Ecuador 20ct Single Davidoff Of Geneva Mehari's Ecuador Wood 50ct Davidoff Of Geneva Mehari's Java Wood 50ct Davidoff Of Geneva Mehari's Java 20ct Single Davidoff Of Geneva Mehari's Sweet Orient 20ct Single Davidoff Of Geneva Mehari's Brasil 20ct Single Davidoff Of Geneva Mehari's Brasil Wood 50ct Davidoff Of Geneva Panter Mignon 10ct. -

1 CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT Dated As of 27 September 2010

CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT dated as of 27 September 2010 among IMPERIAL TOBACCO LIMITED AND THE EUROPEAN UNION REPRESENTED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION AND EACH MEMBER STATE LISTED ON THE SIGNATURE PAGES HERETO 1 ARTICLE 1 DEFINITIONS Section 1.1. Definitions........................................................................................... 7 ARTICLE 2 ITL’S SALES AND DISTRIBUTION COMPLIANCE PRACTICES Section 2.1. ITL Policies and Code of Conduct.................................................... 12 Section 2.2. Certification of Compliance.............................................................. 12 Section 2.3 Acquisition of Other Tobacco Companies and New Manufacturing Facilities. .......................................................................................... 14 Section 2.4 Subsequent changes to Affiliates of ITL............................................ 14 ARTICLE 3 ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT INITIATIVES Section 3.1. Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives............................ 14 Section 3.2. Support for Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives......... 14 ARTICLE 4 PAYMENTS TO SUPPORT THE ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT COOPERATION ARTICLE 5 NOTIFICATION AND INSPECTION OF CONTRABAND AND COUNTERFEIT SEIZURES Section 5.1. Notice of Seizure. .............................................................................. 15 Section 5.2. Inspection of Seizures. ...................................................................... 16 Section 5.3. Determination of Seizures................................................................ -

Imperial Tobacco Group Plc Interim Management Statement for the Nine Months Ended 30 June 2015

IMPERIAL TOBACCO GROUP PLC INTERIM MANAGEMENT STATEMENT FOR THE NINE MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2015 STRATEGIC PROGRESS CONTINUES – ON TRACK FOR FULL YEAR Strengthening our Portfolio • Excellent results from Growth Brands; underlying net revenue, underlying volume and market share up 14 per cent, 10 per cent and 100 bps respectively • Continued success of brand migrations; 13 complete (8 in FY15), 21 ongoing; high level of consumer retention • Growth and Specialist Brands proportion of reported tobacco net revenue up 580 bps to 59 per cent Developing our Footprint • Continued progress in Growth Markets: underlying net revenue down 1 per cent; up 3 per cent ex Iraq • Improving underlying net revenue growth of 1 per cent in Returns Markets • Total underlying net revenue flat and volumes down 6 per cent (net revenue up 1 per cent and volumes down 4 per cent ex Iraq) • Acquisition of US assets completed; ITG Brands fully operational and integration progressing to plan Cost Optimisation • Focus on complexity reduction, improved ways of working and cost efficiencies ongoing • Cost optimisation programme remains on track to deliver £85 million savings in FY15 Capital Discipline • Expect cash conversion of c.90 per cent for the full year with consistent focus on managing working capital • Continuing commitment to ongoing debt reduction • On track to deliver dividend growth of 10 per cent for the full year Overview 9 months to 30 June Change Constant 2015 2014 Actual Currency1 Underlying2 Growth Brands volume bn SE 105.4 91.7 +15% - +10% Tobacco net revenue3 £m 4,435 4,632 R -4% +2% 0% Total Tobacco volume3 bn SE 207.4 213.3 -3% - -6% 1 Change at constant currency removes the effect of exchange rate movements on the translation of the results of our overseas operations. -

Negativliste. Tobaksselskaber. Oktober 2016

Negativliste. Tobaksselskaber. Oktober 2016 Læsevejledning: Indrykket til venstre med fed tekst fremgår koncernen. Nedenunder, med almindelig tekst, fremgår de underliggende selskaber, som der ikke må investeres i. Alimentation Couche Tard Inc Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc Couche-Tard Inc Alliance One International Inc Alliance One International Inc Altria Group Inc Altria Client Services Inc Altria Consumer Engagement Services Inc Altria Corporate Services Inc Altria Corporate Services International Inc Altria Enterprises II LLC Altria Enterprises LLC Altria Finance Cayman Islands Ltd Altria Finance Europe AG Altria Group Distribution Co Altria Group Inc Altria Import Export Services LLC Altria Insurance Ireland Ltd Altria International Sales Inc Altria Reinsurance Ireland Ltd Altria Sales & Distribution Inc Altria Ventures Inc Altria Ventures International Holdings BV Batavia Trading Corp CA Tabacalera Nacional Fabrica de Cigarrillos El Progreso SA Industria de Tabaco Leon Jimenes SA Industrias Del Tabaco Alimentos Y Bebidas SA International Smokeless Tobacco Co Inc National Smokeless Tobacco Co Ltd Philip Morris AB Philip Morris Albania Sh pk Philip Morris ApS Philip Morris Asia Ltd Philip Morris Baltic UAB Philip Morris Belgium BVBA Philip Morris Belgium Holdings BVBA Philip Morris Belgrade doo Philip Morris BH doo Philip Morris Brasil SA Philip Morris Bulgaria EEOD Philip Morris Capital Corp Philip Morris Capital Corp /Rye Brook Philip Morris Chile Comercializadora Ltda Philip Morris China Holdings SARL Philip Morris China Management -

Imperial Tobacco Finance

Prospectus Imperial Tobacco Finance PLC A9.4.1.1 (Incorporated with limited liability in England and Wales with registered number 03214426) A9.4.1.2 Imperial Tobacco Finance France SAS (A société par actions simplifiée incorporated in France) €15,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme Irrevocably and unconditionally guaranteed by Imperial Tobacco Group PLC A9.4.1.1 (Incorporated with limited liability in England and Wales with registered number 03236483) A9.4.1.2 This Prospectus amends, restates and supersedes the offering circular dated 21st February 2014. Any Notes issued after the date hereof under the Debt Issuance Programme described in this Prospectus (the “Programme”) are issued subject to the provisions set out herein. This Prospectus will not be effective in respect of any Notes issued under the Programme prior to the date hereof. Under the Programme, Imperial Tobacco Finance PLC (“Imperial Finance” or an “Issuer”) and Imperial Tobacco Finance France SAS A6.1 (“Imperial Finance France” or an “Issuer” and together with Imperial Finance “the Issuers”), subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, may from time to time issue debt securities (the “Notes”) guaranteed by Imperial Tobacco Group PLC (“Imperial Tobacco” or the “Guarantor”) and Imperial Tobacco Limited (“ITL”). Please see the Trust Deed dated 6th February 2015 (the “Trust Deed”) which is available for viewing by Noteholders as described on page 124 for further details about the Imperial Tobacco guarantee and page 98 for further details regarding the ITL guarantee. The aggregate nominal amount of Notes outstanding will not at any time exceed €15,000,000,000 (or the equivalent in other currencies). -

We Are a Unique Company«

INFORMATIONinside ABOUT SWEDISH MATCH FOR SHAREHOLDERS AND OTHER STAKEHOLDERS # march 2002 1 STIG-GÖRAN NILSSON Strong earnings and positive organic growth Swedish Match reports strong earnings and 8-per- cent organic growth, despite the weakening world economy. Operating income improved further dur- ing the fourth quarter, resulting in full-year increase of 16 percent. Earnings per share increased by a full 28 percent to SEK 3.54. Page 2 Success for cigars in North America Swedish Match increased both its sales volumes and its market shares for machine-made cigars in North America. The explanations for this success include a more efficient sales force and improved marketing. »This is an extremely dynamic market. You can’t afford to sit still for a single minute,« says David Price, head of marketing. Page 2–3 2001 best year ever for shareholders LENNART SUNDÉN: For Swedish Match shareholders, 2001 was the best year since the company’s stock market introduction in 1996. The share price rose 51 percent and the total return to shareholders was in excess of 53 percent, making the Swedish Match share the best- »We are a performing of the most actively traded shares on the Stockholm Exchange. The factors behind the share’s surge include the company’s strong finances, stable and positive cash flow and underlying sales growth, despite a declining economy. Page 7 unique company« Danish paradise for »We have turned the industry’s problems into an opportunity. We focus on Nordic tobacco lovers those niche areas that are growing and where profitability is high, with smoke- The Nordic region’s most prestigious tobacco store, W.Ø. -

Case No COMP/M.3191 - PHILIP MORRIS / PAPASTRATOS

EN Case No COMP/M.3191 - PHILIP MORRIS / PAPASTRATOS Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 02/10/2003 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 303M3191 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 02/10/2003 SG (2003) D/232408 In the published version of this decision, PUBLIC VERSION some information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 concerning non-disclosure of MERGER PROCEDURE business secrets and other confidential ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION information. The omissions are shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a To the notifying parties general description. Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Case No COMP/M.3191 - PHILIP MORRIS/PAPASTRATOS Notification of 2.9.2003 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 4064/891 1. On 2.9.2003, Philip Morris Holland BV notified its intention to acquire control of the whole of Papastratos Cigarette Manufacturing SA (“Papastratos”) within the meaning of Art 3(1)b of the Merger Regulation. 2. The Commission has concluded that the notified operation falls within the scope of the Merger Regulation as amended and does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the common market and with the functioning of the EEA Agreement. I. THE PARTIES 3. Philip Morris Holland BV is a subsidiary of Philip Morris International Inc. ("Philip Morris"), an affiliate of Altria Group, Inc.