Mahler's Wunderhorn World of Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vicent Alberola Cv

VICENT ALBEROLA CLARINET PROFESSOR Academic record His studies were done with Walter Boeykens at the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp, Belgium, and at the same time with George Pieterson (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra) and Larry Combs (Chicago Symphony Orchestra). Professional experience Founder of the Alberola MMCV Valencia, Professor at the ESMAR Higher Music Degree School and guest conductor at the Perm Opera, Russia. At the same time, he is also the first clarinet of the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, World Orchestra for Peace (WOP) and Les Dissonances de Paris. Alberola was for more than 20 years the first clarinet of the Madrid Opera and the Galician Symphony. During the last decade he has been the first guest clarinet with the Vicent Alberola Royal Concertgebow Orchestra, New York Philarmonic Orchestra, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Orchester Les He studied with Walter Boeykens at the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp, Dissonances and the MMCK Tokyo Orchestra, groups with which he has Belgium, and with George Pieterson had the opportunity to perform the great repertoire. symphonic under and Larry Combs. the baton of teachers such as Claudio Abbado, Mariss Jansons, Valery Gergiev, Riccardo Muti, Daniele Gatti, Daniel Harding, Andris Nelsons, He has played with orchestras such as Royal Concertgebow Orchestra, Gustavo Dudamel, Alan Gilbert and Nicola Luisotti, among others. New York Philarmonic Orchestra, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Mahler In 2003 he was appointed conductor of the Young Orchestra of the Chamber Orchestra, Orchester Les Madrid Opera and in 2007 conductor of the Young Orchestra of Soria. Dissonances and the MMCK Tokyo Vicent Alberola has directed the following operas at the Teatro Real de Orchestra. -

Violin Concertos Orchestra Mozart Isabelle Faust Claudio Abbado Franz Liszt Violin Concertos

BERG • BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTOS ORCHESTRA MOZART ISABELLE FAUST CLAUDIO ABBADO FRANZ LISZT VIOLIN CONCERTOS ALBAN BERG (1885-1935) Violin Concerto ‘To the Memory of an Angel’ “À la mémoire d’un ange” / “Dem Andenken eines Engels” 1 | I. Andante - Allegretto 11’51 2 | II. Allegro - Adagio 16’07 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Violin Concerto in D major op.61 Ré majeur / D-Dur 3 | I. Allegro ma non troppo - Adagio 22’55 4 | II. Larghetto 9’21 5 | III. Rondo allegro 8’34 Isabelle Faust, violin Orchestra Mozart Claudio Abbado Orchestra Mozart Flutes Chiara Tonelli, Mattia Petrilli Oboes Lucas Macias Navarro, Miriam Olga Pastor Burgos Clarinets Giammarco Casani, Maria Francesca Latella (Berg: bass clarinet) Erik Masera*, Manuela Vettori*” Alto saxophone* Alda Dalle Lucche Bassoons Guilhaume Santana, Zeynep Koyuoglu Contrabassoon Klaus Lohrer* Horns Alessio Allegrini, Giuseppe Russo, José Castello, Geremia Iezzi Trumpets Alexander Kirn, Jakob Gollien Trombones* Andrea Conti, Federico Gerato, Martin Schippers Tuba* Alessandro Fossi Timpani Robert Kendell Percussion* Giovanni Franco, Gabriele Lattuada Harp* Nabila Chajai Violins 1 Raphael Christ, Lorenza Borrani, Yunna Shevchenko, Henja Semmler Francesco Senese, Manuel Kastl, Giacomo Tesini, Tilman Büning Claudia Schmidt, Timoti Fregni, Andrea Mascetti, Gabrielle Shek Lavinia Morelli, Tim Summers Violins 2 Etienne Abelin, Gisella Curtolo, Michal Duris, Paolo Lambardi Nicola Bignami, Gian Maria Lodigiani, Jo Marie Sison, Federica Vignoni Jana Kuhlmann, Massimiliano Canneto, Gunilla Kerrich, -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Tuesday 2 June 2015 7.30pm Barbican Hall LSO INTERNATIONAL VIOLIN FESTIVAL JANINE JANSEN Edward Rushton I nearly went, there (UK premiere) Mendelssohn Violin Concerto SundayINTERVAL 21 September 2014 7.30pm BarbicanMahler Symphony Hall No 5 London’s Symphony Orchestra MAKEDaniel HardingUP A TITLE conductor HERE Janine Jansen violin Composer Work ComposerConcert finishes Work approx 10pm Composer Work The LSO International Violin Festival is Namegenerously conductor supported by Jonathan Moulds CBE Name soloist Concert finishes approx ?.??pm International Violin Festival Media Partner 2 Welcome 2 June 2015 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Tonight we are delighted to welcome back the PANUFNIK COMPOSERS WORKSHOP 2015 LSO’s Principal Guest Conductor Daniel Harding, following a tour of Germany and Switzerland with Witness the fascinating process of putting together the Orchestra. This evening’s concert begins with and rehearsing a new orchestral piece as the LSO the UK premiere of a new work, I nearly went, there, works with six of the UK’s most promising emerging by British composer Edward Rushton, who first composers, under the guidance of Colin Matthews wrote for the LSO in 2008 when his piece Everything and conductor François-Xavier Roth. The workshops Goes So Fast, which Daniel Harding also conducted, take place on Friday 5 June at LSO St Luke’s. The was commissioned as part of the UBS Soundscapes: composers taking part are Michael Cryne, Michael Pioneers scheme. Cutting, Vitalija Glovackyte˙, Alex Roth, Jack Sheen and Michael Taplin. Tickets are free; to reserve your Our soloist is violin virtuoso Janine Jansen, a great place, phone the Box Office on 020 7638 8891. -

MAHLER LORIN MAAZEL P2013 Philharmonia Orchestra C2013 Signum Records SYMPHONY NO

CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. Recorded at Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall, London, 17 April 2011 Producer – Misha Donat Engineer – Jonathan Stokes, Classic Sound Ltd Design – With Relish (for the Philharmonia Orchestra) and Darren Rumney Cover image CLebrecht Music & Arts MAHLER LORIN MAAZEL P2013 Philharmonia Orchestra C2013 Signum Records SYMPHONY NO. 2, RESURRECTION 24 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. “On Mahler” Mahler’s earlier symphonies frequently draw GUSTAV MAHLER on the world of his Wunderhorn songs – A century after his death, Mahler’s music settings of simple folk poems about birds and SYMPHONY NO. 2, RESURRECTION resonates more powerfully than ever. Its animals, saints and sinners, soldiers and their unique mix of passionate intensity and lovers. But this apparently naive, even childlike CD1 terrifying self-doubt seems to speak directly to tone is found alongside vast musical our age. One moment visionary, the next 1 I. Allegro maestoso 25.13 canvasses that depict the end of the world. In despairing, this is music that sweeps us up in quieter, more intimate movements, Mahler CD2 its powerful current and draws us along in its seems to speak intimately and directly to the 1 II. Andante moderato. Sehr gemächlich 11.25 drama. We feel its moments of ecstatic rapture listener, but the big outer movements are 2 III. Scherzo. In ruhig fliessender Bewegung 12.14 and catastrophic loss as if they were our own. -

Mahler Chamber Orchestra Sir George Benjamin

MAHLER CHAMBER ORCHESTRA SIR GEORGE BENJAMIN 7. SEPTEMBER 2020 ELBPHILHARMONIE GROSSER SAAL Montag, 7. September 2020 | 18:30 & 21 Uhr | Elbphilharmonie Großer Saal Elbphilharmonie Abo 1 | 1. Konzert MAHLER CHAMBER ORCHESTRA PIERRE-LAURENT AIMARD KLAVIER DIRIGENT SIR GEORGE BENJAMIN Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) Concertino für Klavier, zwei Violinen, Viola, Klarinette, Horn und Fagott (1925) Moderato Piu mosso Con moto Allegro ca. 20 Min. George Benjamin (*1960) Duet für Klavier und Orchester (2008) ca. 10 Min. Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) Ma mère l’oye / Ballettmusik (1911) Prélude Danse du rouet et scène (Tanz des Spinnrads und Szene) Pavane de la belle au bois dormant (Pavane der Schönen im schlafenden Wald) Les entretiens de la belle et de la bête (Die Schöne und das Biest) Petit poucet (Der kleine Däumling) Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes (Laideronnette, Kaiserin der Pagoden) Le jardin féerique (Der Feengarten) ca. 30 Min. WILLKOMMEN Mit seiner unprätentiösen Art und Musik von »schimmernder Schönheit« (The Guardian) nahm Sir George Benjamin das Hamburger Publikum schon in der Saison 2018/19 für sich ein. Nun kehrt der hochdekorierte Komponist und Dirigent als einer der Ersten nach der Corona-Zwangspause zurück an die Elbe. Begleitet wird er vom fulmi- nanten Mahler Chamber Orchestra, ausgewiese- nen Kennern seiner Musik, und dem Pianisten, Neue-Musik-Spezialisten und geschätzten Freund Pierre-Laurent Aimard. Ebenso delikat wie die Besetzung ist das neu zusammengestellte Programm: Ravel schrieb seine märchenhafte Suite »Ma mère l’oye« für Kinderohren; aus Janáčeks Concertino tönen Igel, Eichhörnchen und Eule. Und Benjamins »Duet« wandelt durch karge, verschlungene Klangland- schaften. DIE MUSIK KLEINE ZOOLOGIE Leoš Janáček: Concertino Die Domäne des großen Opernkomponisten Leoš Janáček waren Menschen, die stets existenziell und seelisch am Sir George Benjamin Abgrund balancieren. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 128, 2008-2009

Music Director James Levine | Conductor Emeritus Bernard Haitink | Music Director Laureate Seiji Ozawa | SYAAP ] O R C H E STf R 2008-2009 SEASON I VHMB WfBSfSBe^m mum E3K MSgfc'tixsm IK HEP the Clarendon BACK BAY 3K The Way to Live i|!l . mi '' I II !l I II, :1 » !«! ? i nr k Ct isi. ' IB i w: i Hi- ' l !! ; a |* »f '«^ ^.. it a*H J MP IMS a £#.l W; PJMJ » 1 :,]„,, ii 3lj.W • ii «'• '.,'? ir ill!! 1 iiiP !IP* !Iii 1 il mil :'il . n; : if in ~ r ;f>«w mi i v m F1&& n=:2 RENDERING BY NEOSCAPE INTRODUCING FIVE STAR LIVING™ WITH UNPRECEDENTED SERVICES AND AMENITIES DESIGNED BY ROBERT A.M. STERN ARCHITECTS, LLP ONE TO FOUR BEDROOM LUXURY CONDOMINIUM RESIDENCES STARTING ON THE 15TH FL0( CORNER OF CLARENDON AND STUART STREETS THE CLARENDON SALES AND DESIGN GALLERY, 14 NEWBURY STREET, BOSTON. MA 617.267.4001 www.theclarendonbackbay.com BRELATED DC/\LcOMPAN REGISTERED WITH THE U.S. GREEN BUILDING COUNCIL WITH ANTICIPATED LEED SILVER CERTIFICATION The artist's rendering shown may not be representative of the building. The features described and depicted herein are based upon current development plans, whic subject to change without notice. No guarantee is made that said features will be built, or, if built, will be of the same type, size, or nature as depicted or described. No Fe agency has judged the merits or value, if any, of this property. This is not an offer where registration is reguired prior to any offer being made. Void where prohibits Table of Contents | Week 24 15 BSO NEWS 23 ON DISPLAY IN SYMPHONY HALL 25 BSO MUSIC DIRECTOR JAMES LEVINE 28 THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 33 THIS WEEK'S PROGRAM Notes on the Program 35 Ludwig van Beethoven 47 Gustav Mahler 63 To Read and Hear More. -

DAVID AFKHAM Conducts the GUSTAV MAHLER JUGENDORCHESTER on Its Silver Jubilee Tour in Spring 2012

1987 – 2012 GUSTAV MAHLER JUGENDORCHESTER Musicians for Europe Shooting Star DAVID AFKHAM conducts the GUSTAV MAHLER JUGENDORCHESTER on its Silver Jubilee Tour in Spring 2012 „It is truly wonderful for the GUSTAV MAHLER JUGENDORCHESTER as well as for all presenters of the Easter Tour 2012 to have DAVID AFKHAM - with whom the orchestra has a long-standing relationship - taking over after Ingo Metzmacher´s cancellation on short notice due to his shoulder injury.“ (Alexander Meraviglia- Crivelli, Secretary General of the GUSTAV MAHLER JUGENDORCHESTER). Recently appointed „Ambassador UNICEF Austria“, the GUSTAV MAHLER JUGENDORCHESTER will perform, in the Easter Tour 2012, twelve concerts with two exceptional Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou programmes in seven European countries under the baton of DAVID AFKHAM and with Swedish DAVID AFKHAM, first winner of the „Nestlé and soprano IRENE THEORIN. Salzburg Festival Young Conductors Award“ 2010, will lead the Easter Tour 2012 of the Besides appearances in the orchestra’s GUSTAV MAHLER JUGENDORCHESTER, th founding cities Vienna, Graz, Prague, and which is marking the 25 anniversary of the Warsaw, the GUSTAV MAHLER orchestra. JUGENDORCHESTER will perform, as every year, in some of the most important European DAVID AFKHAM is rapidly establishing a concert halls: two concerts in the Vienna reputation as one of the most sought after Musikverein, two concerts at the Fundaçao conductors of our times, and Bernard Haitink Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon, as well as one has been his mentor for a long time. After concert in the Laeiszhalle Hamburg and the conducting renowned orchestras, such as the Auditorio Nacional in Madrid prove the exceptional Cleveland Orchestra, the Los Angeles artistic reputation of the GUSTAV MAHLER Philharmonic, the DSO Berlin, Orchestre National JUGENDORCHESTER. -

LUCERNE FESTIVAL ORCHESTRA Sonntag, 08.11.2015 · 16.00 Uhr

LUCERNE FESTIVAL ORCHESTRA Sonntag, 08.11.2015 · 16.00 Uhr KONZERTHAUS DORTMUND LUCERNE FESTIVAL ORCHESTRA ANDRIS NELSONS DIRIGENT RUDOLF BUCHBINDER KLAVIER Abo: Orchesterzyklus III – Symphonie um Vier In unserem Haus hören Sie auf allen Plätzen gleich gut – leider auch Husten, Niesen und Handy- klingeln. Ebenfalls aus Rücksicht auf die Künstler bitten wir Sie, von Bild- und Tonaufnahmen während der Vorstellung abzusehen. Wir danken für Ihr Verständnis! 2,50 E 4I5 Ludwig van Beethoven LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827) Konzert für Klavier und Orchester Nr. 1 C-Dur op. 15 (1800) Allegro con brio Largo Rondo. Allegro scherzando – Pause ca. 16.45 Uhr – GUSTAV MAHLER (1860 – 1911) Sinfonie Nr. 5 cis-moll (1904) I. Abteilung Trauermarsch. In gemessenem Schritt, streng, wie ein Kondukt Stürmisch bewegt, mit größter Vehemenz II. Abteilung Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell III. Abteilung Adagietto. Sehr langsam Rondo-Finale. Allegro – Ende ca. 18.20 Uhr – 6I7 PROGRAMM 8I9 DEBÜT EINES GENIES Beethoven’s Zimmer statt hatte, stand das Klavier für die Blasinstrumente einen halben Ton zu LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN KLAVIERKONZERT NR. 1 C-DUR OP. 15 tief. Beethoven ließ auf der Stelle diese und so auch die übrigen statt nach a, nach b stimmen und spielte seine Stimme aus Cis«. Einen ungeheuerlichen Vorgang hat Wegeler hier beobach- Besprechungen, Kritiken und Berichte über das 1. Klavierkonzert Ludwig van Beethovens ähneln tet. Wer vermag schon eine Klavierstimme vom Blatt in eine andere Tonart transponieren, wie sich oft in ihrem ersten Satz: »Beethovens erstes Konzert ist eigentlich nicht sein erstes«. Es es Beethoven hier wahrscheinlich getan hat? stimmt, vor Beethovens Opus 15 ist noch sein B-Dur-Konzert entstanden, das später als 2. -

Mahler Chamber Orchestra

CARTE BLANCHE AU… MAHLER CHAMBER ORCHE STRA ALBRECHT MAYER , haut bois TUGAN SOKHIEV , direction Stravinsky, Pulcinella Suite Strauss, Concerto pour hautbois Mendelssohn, Symphonie italienne 19 au 25 janvier 2009 22 rue des Thermopyles - 75014 Paris, France - 33 (0)1 45 66 97 11 - [email protected] http://carteblanchemusique.free.fr - RCS 491 044 020 - Licence d’Entrepreneur de Spectacles 7503165 MAHLER CHAMBRE ORCHE STRA Le Mahler Chamber Orchestra a été fondé en 1997, à l’initiative de Claudio Abbado et de quelques-uns des musiciens de l’Orchestre Gustave Mahler de la Jeunesse, qui ne voulaient pas voir leur collaboration s’arrêter en raison de la limite d’âge. La curiosité artistique, le souci de développer un répertoire aussi vaste que possible, et le souhait de réaliser tout ceci au plus haut niveau, ont alors caractérisé le travail de l’ambitieux corps musical et le caractérisent toujours. Musique de chambre et musique symphonique, opéras classiques et grandes premières se retrouvent dans le répertoire, qui couvre les périodes allant du baroque au contemporain. Pour répondre de manière adéquate à ces hautes exigences, l’orchestre s’est assuré, depuis ses débuts, le concours de partenaires renommés, aussi bien en ce qui concerne les chefs et solistes invités que les lieux de manifestation. Après son fondateur Claudio Abbado, c’est surtout Daniel Harding qui a influencé de la manière la plus décisive le développement de l’orchestre. Tout d’abord premier chef invité de l’orchestre, Harding en est depuis l’été 2003 le principal directeur musical et dirige une grande partie des quelques quatre-vingt concerts et premières ayant lieu chaque année. -

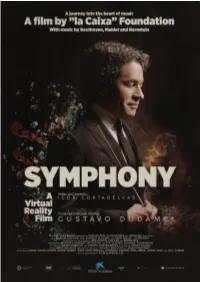

Symphony: a Singular Journey to the Heart of Music Under the Baton of Gustavo Dudamel

Press release After four years in production, ”la Caixa” Foundation announces the world premiere of this emotional experience delivered through virtual reality technology Symphony: a singular journey to the heart of music under the baton of Gustavo Dudamel The Symphony project employs virtual reality (VR) technology to offer spectators a chance to experience and enjoy classical music as they have never done before, inviting them to feel like one of the musicians in the orchestra. Under the baton of Gustavo Dudamel and accompanied by the more than one hundred musicians that make up the internationally acclaimed Mahler Chamber Orchestra, audiences will have the opportunity to hear music in a way they have previously never been able to, and even travel through the interior of the instruments. The premiere of the two films that comprise this itinerant project - written and directed by Igor Cortadellas - will take place at CosmoCaixa, where they can be seen up to 8 October before beginning a tour which will last ten years and take in around a hundred towns and cities in Spain and Portugal. The main feature of this emotional journey guided by the celebrated Venezuelan conductor will be compositions by Ludwig van Beethoven, for whom 2020 marks the 250th anniversary of his birth, as well as Gustav Mahler and Leonard Bernstein. “With this extraordinary and captivating experience we want to contribute to disseminating classical music and make it available to the wider public, in a journey without precedent to the heart of the human soul”, said the deputy general director of the ”la Caixa” Foundation, Elisa Durán. -

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director Thursday, January 31, 2019 at 8:00pm Saturday, February 2, 2019 at 8:00pm Sir Andrew Davis, conductor Lise Davidsen, soprano (Sieglinde) Simon O’Neill, tenor (Siegmund) Brindley Sherratt, bass (Hunding) Richard Wagner “The Ride of the Valkyries” from Act III of Die Walküre Alban Berg Three Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 6 (1929 revision) I. Präludium II. Reigen III. Marsch Intermission Richard Wagner Act I of Die Walküre Scene I Scene II Scene III The appearances of Sir Andrew Davis this season are made possible by Hans and Susan Brenninkmeyer. As a courtesy to musicians, guest artists, and fellow concertgoers, please put your phone away and on silent during the performance. SURTITLES TM operated by John Sharpe SURTITLES TM written and produced by Gunta Dreifelds for the Canadian Opera Company SURTITLES TM invented at the Canadian Opera Company in 1983 and introduced worldwide with their production of Elektra by Richard Strauss JANUARY 31 & FEBRUARY 2, 2019 25 ABOUT THE WORKS Richard Wagner “The Ride of the Valkyries” from Act III of Die Walküre Born: Leipzig, Germany, May 22, 1813 5 Died: Venice, Italy, February 13, 1883 min Composed: Die Walküre, 1851–1856; concert version of “The Ride of the Valkyries”, 1863 “The Ride of the Valkyries” music from Such concertizing of excerpts was a conscious the beginning of Act III of Die Walküre (The promotional strategy by Wagner to drum up Valkyrie), is arguably the most recognizable of support for his Ring project—and it worked. Wagner’s music from his massive four-opera In 1864, he resumed work on Siegfried and cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of later completed Götterdämmerung, eventually the Nibelungs), and perhaps from his entire staging the entire cycle in 1876 at a festival in output. -

Page 1/4 2017 Summer Festival Theme of “Identity”

2017 Summer Festival Theme of “Identity” Who am I? The issue of identity illuminates the human condition in the present and through history in its relation to origin, homeland, faith, culture, and religion. How did we become the people we are? And how are we changed by our current environment? Paradigmatic answers to these questions can be found in the fates of such composers as Béla Bartók, Gustav Mahler, Sergei Prokofiev, and Dmitri Shostakovich. But they also come up in general for every musician involved in the international concert scene. Like nomads they travel around the world, performing today in New York and tomorrow in Tokyo. And the issue of identity is highly controversial, as we see in the case of refugees who are coming to Europe from war zones and who have to choose between the desire to integrate and the preservation of what is uniquely their own. Selected Themes/Projects/Related Events Monteverdi Cycle English Baroque Soloists | Monteverdi Choir | Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor | Soloists The operas of Monteverdi reach back to the KKL Luzern very origins of Western culture and its myths, and to the birth of the genre of opera. They 22 August | 19.30 | L’Orfeo depict humans in all their emotions, 25 August | 18.30 | Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria distortions, and psychological depths. 26 August | 18.30 | L’incoronazione di Poppea Concerts exploring the theme of “Identity” Special Event Day on Sunday, 27 August from different perspectives KKL Luzern 1 “The Path of Slavery” – Music from six Hespèrion XXI | La Capella Reial de Catalunya | centuries Jordi Savall conductor | Soloists 2 Kodály The Imperial Adventures of Háry Symphony Concert with the Basel Symphony page 1/4 János Orchestra, also for children (ages 7 and up) 3 Recital for violin, cello, and piano: works by Patricia Kopatchinskaja violin | Jay Campbell Enescu, Kodály, Ravel cello | Polina Leschenko piano 4 Mahler: Symphony No.