Removal of Viruses from Lebanese Fig Varieties Using Tissue Culture and Thermotherapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPPO Reporting Service

ORGANISATION EUROPEENNE ET MEDITERRANEENNE POUR LA PROTECTION DES PLANTES EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN PLANT PROTECTION ORGANIZATION EPPO Reporting Service NO. 6 PARIS, 2020-06 General 2020/112 New data on quarantine pests and pests of the EPPO Alert List 2020/113 New and revised dynamic EPPO datasheets are available in the EPPO Global Database 2020/114 EPPO report on notifications of non-compliance Pests 2020/115 Anoplophora glabripennis found in South Carolina (US) 2020/116 Update on the situation of Popillia japonica in Italy 2020/117 Update of the situation of Tecia solanivora in Spain 2020/118 Dryocosmus kuriphilus found again in the Czech Republic 2020/119 Eradication of Paysandisia archon from Switzerland 2020/120 Eradication of Comstockaspis perniciosa from Poland 2020/121 First report of Globodera rostochiensis in Uganda Diseases 2020/122 First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in Poland 2020/123 Update of the situation of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in the United Kingdom 2020/124 Update of the situation of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in the USA 2020/125 Tomato brown rugose fruit virus does not occur in Egypt 2020/126 Eradication of tomato chlorosis virus from the United Kingdom 2020/127 Tomato spotted wilt virus found in Romania 2020/128 First report of High Plains wheat mosaic virus in Ukraine 2020/129 Update on the situation of Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii in Slovenia 2020/130 Update on the situation of Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii in Italy 2020/131 First report of Peronospora aquilegiicola, the downy mildew of columbines in Germany Invasive plants 2020/132 Lycium ferocissimum in the EPPO region: addition to the EPPO Alert List 2020/133 First report of Amaranthus tuberculatus in Croatia 2020/134 First report of Microstegium vimineum in Canada 2020/135 Disposal methods for invasive alien plants 2020/136 EPPO Alert List species prioritised 21 Bld Richard Lenoir Tel: 33 1 45 20 77 94 Web: www.eppo.int 75011 Paris E-mail: [email protected] GD: gd.eppo.int EPPO Reporting Service 2020 no. -

PDF Download

fmicb-11-621179 December 26, 2020 Time: 15:34 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 08 January 2021 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.621179 Next-Generation Sequencing Reveals a Novel Emaravirus in Diseased Maple Trees From a German Urban Forest Artemis Rumbou1*, Thierry Candresse2, Susanne von Bargen1 and Carmen Büttner1 1 Faculty of Life Sciences, Albrecht Daniel Thaer-Institute of Agricultural and Horticultural Sciences, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2 UMR 1332 Biologie du Fruit et Pathologie, INRAE, University of Bordeaux, UMR BFP, Villenave-d’Ornon, France While the focus of plant virology has been mainly on horticultural and field crops as well as fruit trees, little information is available on viruses that infect forest trees. Utilization of next-generation sequencing (NGS) methodologies has revealed a significant number of viruses in forest trees and urban parks. In the present study, the full-length genome of a novel Emaravirus has been identified and characterized from sycamore maple Edited by: (Acer pseudoplatanus) – a tree species of significant importance in urban and forest Ahmed Hadidi, areas – showing leaf mottle symptoms. RNA-Seq was performed on the Illumina Agricultural Research Service, HiSeq2500 system using RNA preparations from a symptomatic and a symptomless United States Department of Agriculture, United States maple tree. The sequence assembly and analysis revealed the presence of six genomic Reviewed by: RNA segments in the symptomatic sample (RNA1: 7,074 nt-long encoding the viral Beatriz Navarro, replicase; RNA2: 2,289 nt-long encoding the glycoprotein precursor; RNA3: 1,525 nt- Istituto per la Protezione Sostenibile delle Piante, Italy long encoding the nucleocapsid protein; RNA4: 1,533 nt-long encoding the putative Satyanarayana Tatineni, movement protein; RNA5: 1,825 nt-long encoding a hypothetical protein P5; RNA6: Agricultural Research Service, 1,179 nt-long encoding a hypothetical protein P6). -

A New Emaravirus Discovered in Pistacia from Turkey

Virus Research 263 (2019) 159–163 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Virus Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/virusres Short communication A new emaravirus discovered in Pistacia from Turkey T ⁎ Nihal Buzkana, , Michela Chiumentib, Sébastien Massartc, Kamil Sarpkayad, Serpil Karadağd, Angelantonio Minafrab a Dep. of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Sütçü Imam, Kahramanmaras 46060, Turkey b Institute for Sustainable Plant Protection, CNR, Via Amendola 122/D, Bari 70126, Italy c Plant Pathology Laboratory, TERRA-Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, University of Liège, Passage des Déportés, 2, 5030 Gembloux, Belgium d Pistachio Research Institute, University Blvd., 136/C 27060 Sahinbey, Gaziantep, Turkey ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: High throughput sequencing was performed on total pooled RNA from six Turkish trees of Pistacia showing Emaravirus different viral symptoms. The analysis produced some contigs showing similarity with RNAs of emaraviruses. High throughput sequencing Seven distinct negative–sense, single-stranded RNAs were identified as belonging to a new putative virus in- Pistachio fecting pistachio. The amino acid sequence identity compared to homologs in the genus Emaravirus ranged from 71% for the replicase gene on RNA1, to 36% for the putative RNA7 gene product. All the RNA molecules were verified in a pistachio plant by RT-PCR and conventional sequencing. Although the analysed plants showeda range of symptoms, it was not possible to univocally associate the virus with a peculiar one. The possible virus transmission by mite vector needs to be demonstrated by a survey, to observe spread and potential effect on yield in the growing areas of the crop. Pistachio (Pistacia spp.) is an important crop worldwide, with a ampelovirus A) and a pistachio variant of a viroid (Citrus bark cracking global production of more than 1 million tons (FAOstat, 2016). -

EPPO Reporting Service

ORGANISATION EUROPEENNE ET MEDITERRANEENNE POUR LA PROTECTION DES PLANTES EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN PLANT PROTECTION ORGANIZATION EPPO Reporting Service NO. 10 PARIS, 2020-10 General 2020/209 New additions to the EPPO A1 and A2 Lists 2020/210 New data on quarantine pests and pests of the EPPO Alert List 2020/211 New and revised dynamic EPPO datasheets are available in the EPPO Global Database 2020/212 Recommendations from Euphresco projects Pests 2020/213 First report of Spodoptera frugiperda in Jordan 2020/214 Trogoderma granarium does not occur in Spain 2020/215 First report of Scirtothrips dorsalis in Mexico 2020/216 First report of Scirtothrips dorsalis in Brazil 2020/217 Scirtothrips dorsalis occurs in Colombia 2020/218 Update on the situation of Megaplatypus mutatus in Italy 2020/219 Update on the situation of Anoplophora chinensis in Croatia 2020/220 Update on the situation of Anoplophora chinensis in Italy 2020/221 Update on the situation of Anoplophora glabripennis in Italy Diseases 2020/222 Eradication of thousand canker disease in disease in Toscana (Italy) 2020/223 First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in the Czech Republic 2020/224 Update on the situation of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in Greece 2020/225 Update on the situation of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in the Netherlands 2020/226 New finding of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum’ in Estonia 2020/227 Haplotypes and vectors of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum’ in Scotland (United Kingdom) 2020/228 First report of wheat blast in Zambia and in -

Meta-Transcriptomic Detection of Diverse and Divergent RNA Viruses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.141184; this version posted June 8, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Meta-transcriptomic detection of diverse and divergent 2 RNA viruses in green and chlorarachniophyte algae 3 4 5 Justine Charon1, Vanessa Rossetto Marcelino1,2, Richard Wetherbee3, Heroen Verbruggen3, 6 Edward C. Holmes1* 7 8 9 1Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity, School of Life and 10 Environmental Sciences and School of Medical Sciences, The University of Sydney, 11 Sydney, Australia. 12 2Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, Westmead Institute for Medical 13 Research, Westmead, NSW 2145, Australia. 14 3School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia. 15 16 17 *Corresponding author: 18 Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity, School of Life and 19 Environmental Sciences and School of Medical Sciences, 20 The University of Sydney, 21 Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. 22 Tel: +61 2 9351 5591 23 Email: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.141184; this version posted June 8, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. -

EPPO Reporting Service

ORGANISATION EUROPEENNE ET MEDITERRANEENNE POUR LA PROTECTION DES PLANTES EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN PLANT PROTECTION ORGANIZATION EPPO Reporting Service NO. 11 PARIS, 2020-11 General 2020/235 New data on quarantine pests and pests of the EPPO Alert List 2020/236 Update on the situation of quarantine pests in Armenia 2020/237 Update on the situation of quarantine pests in Belarus 2020/238 Update on the situation of quarantine pests in Kazakhstan 2020/239 Update on the situation of quarantine pests in Kyrgyzstan 2020/240 Update on the situation of quarantine pests in Moldova 2020/241 New and revised dynamic EPPO datasheets are available in the EPPO Global Database 2020/242 Recommendations from Euphresco projects 2020/243 Questionnaire for the Euphresco project ‘Systems for awareness, early detection and notification of organisms harmful to plants’ 2020/244 Compendium on the Plant Health research priorities for the Mediterranean region Pests 2020/245 First report of Eotetranychus lewisi in Germany 2020/246 Update on the situation of Eotetranychus lewisi in Madeira (Portugal) 2020/247 First report of Stigmaeopsis longus in the Netherlands 2020/248 Update on the situation of Anoplophora glabripennis in France 2020/249 Lycorma delicatula continues to spread in the USA Diseases 2020/250 First report of tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus in France 2020/251 Further spread of Lonsdalea populi in Europe: first records in Portugal and Serbia 2020/252 First report of tomato mottle mosaic virus in the Czech Republic 2020/253 Tomato mottle mosaic virus: addition to the EPPO Alert List Invasive plants 2020/254 Solanum sisymbriifolium in the EPPO region: addition to the EPPO Alert List 2020/255 Alien flora in Italy and new records for Europe 2020/256 Biological control of Acacia longifolia in Portugal 2020/257 Alien plants with potential impacts in Cyprus 2020/258 Amaranthus palmeri and A. -

Evidence to Support Safe Return to Clinical Practice by Oral Health Professionals in Canada During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Repo

Evidence to support safe return to clinical practice by oral health professionals in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A report prepared for the Office of the Chief Dental Officer of Canada. November 2020 update This evidence synthesis was prepared for the Office of the Chief Dental Officer, based on a comprehensive review under contract by the following: Paul Allison, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Raphael Freitas de Souza, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Lilian Aboud, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Martin Morris, Library, McGill University November 30th, 2020 1 Contents Page Introduction 3 Project goal and specific objectives 3 Methods used to identify and include relevant literature 4 Report structure 5 Summary of update report 5 Report results a) Which patients are at greater risk of the consequences of COVID-19 and so 7 consideration should be given to delaying elective in-person oral health care? b) What are the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 that oral health professionals 9 should screen for prior to providing in-person health care? c) What evidence exists to support patient scheduling, waiting and other non- treatment management measures for in-person oral health care? 10 d) What evidence exists to support the use of various forms of personal protective equipment (PPE) while providing in-person oral health care? 13 e) What evidence exists to support the decontamination and re-use of PPE? 15 f) What evidence exists concerning the provision of aerosol-generating 16 procedures (AGP) as part of in-person -

DPG-Arbeitskreisleitung: Mark Varrelmann & Björn Krenz

Deutsche Phytomedizinische Gesellschaft e.V. 53. JAHRESTREFFEN DES ARBEITSKREISES “VIRUSKRANKHEITEN DER PFLANZEN“ 15. bis 16. März 2021 Programm, Abstracts Vorträge/Poster und Teilnehmerliste Erstellung Tagungsband: Sabine von Tiedemann DPG-Arbeitskreisleitung: Mark Varrelmann & Björn Krenz 15.03.2021 Programm 9.00-9.30 Begrüßung und Organisation (Mark Varrelmann und Björn Krenz) 9:30-12:00 Sektion I (Chair: Mark Varrelmann) 9:30 Übersichtsvortrag: Central role of dsRNA in plant-virus interactions Heinlein M Illuminating SBWMV-host interaction – Subcellular localization of CP-RT during 10:20 infection Nico Sprotte, Claudia Janina Strauch, Sabine Bonse and Annette Niehl New approaches to the identification and selection of wheat dwarf virus 10:40 tolerance in wheat Pfrieme A-K, Habekuss A, Will T Five new Mycoviruses isolated from Nectriaceae species correlating with Apple 11:00 Replant Disease Pielhop T, Popp C, Fricke S, Knierim D, Maiss E For the maturation of the coat proteins of Fusarium graminearum virus China 9 11:20 (FgC-ch9) host factors are required Heinze C, Lutz T, Petersen J, Yannik C, de Oliveira C Movement and replication of cassava brown streak virus in cassava (Manihot 11:40 esculenta Crantz) Sheat S, Margria P, Winter S 12:00-13:30 Pause oder Get together mit Wonder 13:30-15:00 Poster-Vorstellung in Reihenfolge 1-12 (Chair: Björn Krenz) 15:00-16:00 Poster-Session mit Wonder 16:00-18:15 Sektion II (Chair: Wilhelm Jelkmann) Erfahrungen mit einem von der Fa. Eurofins angebotenen Verfahren zur 16:00 Entwicklung von Sonden und Primern zum hochempfindlichen qPCR-Nachweis von Tobacco rattle virus RNA1 und RNA2 R. -

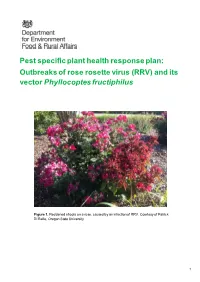

Rose Rosette Virus (RRV) and Its Vector Phyllocoptes Fructiphilus

Pest specific plant health response plan: Outbreaks of rose rosette virus (RRV) and its vector Phyllocoptes fructiphilus Figure 1. Reddened shoots on a rose, caused by an infection of RRV. Courtesy of Patrick Di Bello, Oregon State University. 1 © Crown copyright 2021 You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected] This document is also available on our website at: https://planthealthportal.defra.gov.uk/pests-and-diseases/contingency-planning/ Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: The UK Chief Plant Health Officer Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Room 11G32 York Biotech Campus Sand Hutton York YO41 1LZ Email: [email protected] 2 Contents 1. Introduction and scope ...................................................................................................... 4 2. Summary of threat .............................................................................................................. 4 3. Risk assessments............................................................................................................... 6 4. Actions to prevent outbreaks ............................................................................................. 6 5. Response ........................................................................................................................... -

Diversity and Evolutionary Origin of the Virus Family Bunyaviridae

Diversity and Evolutionary Origin of the Virus Family Bunyaviridae Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Marco Marklewitz aus Hannover Bonn, 2016 Angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Christian Drosten 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Bernhard Misof Tag der Promotion: 21.12.2016 Erscheinungsjahr: 2017 Danksagung Zu Beginn möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei meinem Doktorvater Prof. Christian Drosten bedanken, dass er mir ermöglicht hat, an einem solch vielfältigen und spannenden Thema zu arbeiten. Für Fragen hatte er jederzeit ein offenes Ohr und bei auftretenden Problemen war er immer sehr hilfsbereit. Des Weiteren möchte ich mich herzlich bei meiner Prüfungskommission, bestehend aus meinem 2. Gutachter Prof. Bernhard Misof sowie Prof. Clemens Simmer und PD Dr. Lars Podsiadlowski, für ihre Zeit und Bereitschaft danken mich zu prüfen. Mein ganz besonder Dank geht an PD Dr. Sandra Junglen für ihre hervorragende und kompetente Betreuung während der Jahre meiner Doktorarbeit. Ich habe es als eine Ehre empfunden, ein Teil ihrer zu Beginn noch sehr jungen Arbeitsgruppe zu sein, danke ihr sehr für ihr Vertrauen und hoffe, sie mit meiner (zukünftigen) Arbeit stolz zu machen. Die Atmosphäre in ihrer Arbeitsgruppe ist immer sehr positiv und ermöglicht, die Arbeit mit viel Spaß zu verbinden. Insbesondere möchte ich herausstellen, dass ich ihr für die Möglichkeit besonders dankbar bin, neben meiner Doktorarbeit Feldarbeiten in Panama durchzuführen. Diese Zeit hat mein Leben auf die positivste Art und Weise nachhaltig beeinflusst. Mein großer Dank gilt auch allen Kolleginnen und Kollegen in den Virologie-Laboratorien der Augenklinik für ihre ständige Hilfs- und Diskussionsbereitschaft, ihr Zuhören bei Problemen sowie für ihre Freundschaft über all die Jahre. -

XXVI Brazilian Congress of Virology

Virus Reviews and Research Journal of the Brazilian Society for Virology Volume 20, October 2015, Supplement 1 Annals of the XXVI Brazilian Congress of Virology & X Mercosur Meeting of Virology October, 11 - 14, 2015, Costão do Santinho Resort, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil Editors Edson Elias da Silva Fernando Rosado Spilki BRAZILIAN SOCIETY FOR VIROLOGY BOARD OF DIRECTORS (2015-2016) Officers Area Representatives President: Dr. Bergmann Morais Ribeiro Basic Virology (BV) Vice-President: Dr. Célia Regina Monte Barardi Dr. Luciana Jesus da Costa, UFRJ (2015 – 2016) First Secretary: Dr. Fernando Rosado Spilki Dr. Luis Lamberti Pinto da Silva, USP-RP (2015 – 2016) Second Secretary: Dr. Mauricio Lacerda Nogueira First Treasurer: Dr. Alice Kazuko Inoue Nagata Environmental Virology (EV) Second Treasurer: Dr. Zélia Inês Portela Lobato Dr. Adriana de Abreu Correa, UFF (2015 – 2016) Executive Secretary: Dr Fabrício Souza Campos Dr. Jônatas Santos Abrahão, UFMG (2015 – 2016 Human Virology (HV) Fiscal Councilors Dr. Eurico de Arruda Neto, USP-RP (2015 – 2016) Dr. Viviane Fongaro Botosso Dr. Paula Rahal, UNESP (2015 – 2016) Dr. Davis Fernandes Ferreira Dr. Maria Ângela Orsi Immunobiologicals in Virology (IV) Dr. Flávio Guimarães da Fonseca, UFMG (2015 – 2016) Dr. Jenner Karlisson Pimenta dos Reis, UFMG (2015 – 2016) Plant and Invertebrate Virology (PIV) Dr. Maite Vaslin De Freitas Silva, UFRJ (2015 – 2016) Dr. Tatsuya Nagata, UNB (2015 – 2016) Veterinary Virology (VV) Dr. João Pessoa Araújo Junior, UNESP (2015 – 2016) Dr. Marcos Bryan Heinemann, USP (2015 – 2016) Address Universidade Feevale, Instituto de Ciências da Saúde Estrada RS-239, 2755 - Prédio Vermelho, sala 205 - Laboratório de Microbiologia Molecular Bairro Vila Nova - 93352-000 - Novo Hamburgo, RS - Brasil Phone: (51) 3586-8800 E-mail: F.R.Spilki - [email protected] http://www.vrrjournal.org.br Organizing Committee Dr. -

Assessing the Diversity of Endogenous Viruses Throughout Ant Genomes

fmicb-10-01139 May 21, 2019 Time: 18:26 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 22 May 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01139 Assessing the Diversity of Endogenous Viruses Throughout Ant Genomes Peter J. Flynn1,2* and Corrie S. Moreau2,3 1 Committee on Evolutionary Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States, 2 Department of Science and Education, Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, United States, 3 Departments of Entomology and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States Endogenous viral elements (EVEs) can play a significant role in the evolution of their hosts and have been identified in animals, plants, and fungi. Additionally, EVEs potentially provide an important snapshot of the evolutionary frequency of viral infection. The purpose of this study is to take a comparative host-centered approach to EVE discovery in ant genomes to better understand the relationship of EVEs to their ant hosts. Using a comprehensive bioinformatic pipeline, we screened all nineteen published ant genomes for EVEs. Once the EVEs were identified, we assessed their phylogenetic relationships to other closely related exogenous viruses. A diverse group of EVEs were discovered Edited by: Gustavo Caetano-Anollés, in all screened ant host genomes and in many cases are similar to previously identified University of Illinois exogenous viruses. EVEs similar to ssRNA viral proteins are the most common viral at Urbana–Champaign, United States lineage throughout the ant hosts, which is potentially due to more chronic infection Reviewed by: or more effective endogenization of certain ssRNA viruses in ants. In addition, both David Richard Nash, University of Copenhagen, Denmark EVEs similar to viral glycoproteins and retrovirus-derived proteins are also abundant Frank O’Neill Aylward, throughout ant genomes, suggesting their tendency to endogenize.